By Bob Pearce and Mihail Vladimirov.

Enforcing behaviour

You have referred to tempo many times when we have been talking. To avoid misunderstanding, what do you mean when you talk about ‘tempo’?

Tempo is all about the pace of the game. This means it’s related to both how quick the ball is passed between the players, and whether they use more ‘adventurous’ forwards passes (hence that bit quicker and more direct) or generally ‘unambitious’ sideways or backwards passes (which are generally slower and more cautious).

Also it’s about the intensity the players are displaying in and out of possession, both on and off the ball. If the players are looking deliberately sluggish, cautiously strolling around, with their on-ball actions mostly simple short passes and little or no dribbling, the team would obviously be much slower – especially if the opposition is sitting deep and just standing-off. In contrast, we’d see that players are obviously in a hurry to reach advanced positions with the passes being direct and player movements full of ‘energy’.

Would you say that who is dictating the tempo of the game is more important than who has greater possession?

In a way, yes. This is because possession alone doesn’t lead to control of the game or the ability to create chances yourself or deny the opposition chances.

The easiest way to explain is to picture Red team having possession deep in their own half. By having the ball, Red team will deny Blue team the opportunity to create many chances or raise the tempo of the game. But by having the possession in such unthreatening zones, the Red team will equally be unable to hurt the Blue team.

However, the Blue team’s behaviour should be taken into account here too. If they are on the back foot, sitting deep and standing-off, the Red team with the possession deep in their half would be dictating both the tempo and how the game would be played out. But if the Blue team is focused on fierce pressing from higher up (where the majority of the possession is), it might lead to the Red team becoming uncomfortable in possession.

The Liverpool v Southampton game at Anfield this season was a great example of this. Saints appeared to deliberately cede the possession to Liverpool in order to press them and force the game to be played in Liverpool’s half. While the Reds may have controlled the possession, the visitors dictated the tempo. It proved an excellent example of how controlling the tempo is much more useful than simply having the majority of the ball.

But Red team could also control the tempo by being reactive and ‘gifting’ back the possession to the Blue team. If the Blue team is attacking, hence having more of the ball, Red team could simply drop deep and flood their own half. I’m not suggesting a simple ‘back to the wall’, ‘last ditch’ style of defending or Blue team might eventually breach them due to the risks involved with this type of defending. But if Red team are using very specific marking patterns within their overall defensive strategy, it might lead to the Blue team being more or less nullified. The result will be the Blue team having plenty of the ball but lacking any kind of ‘energy’ to use the ball in a meaningful way to be able to hurt Red team. This will effectively lead to Blue team just passing the ball around, lacking ideas of how to be penetrative. The tempo would drop to a sluggish tempo with the Blue team lacking fresh attacking ideas, and the Red team should thrive in this context.

Of course the situation which is most often seen is that the team in possession is actually the team setting the tempo too. This is generally due to such teams being attack-oriented. They try to use their possession in a proactive and clearly attacking way, meaning high intensity both with and without the ball, and on the ball and off. They have the mindset and general tactical strategy to provide what is required to not simply boss the ball but also control the tempo. It’s always harder to defend against a team that doesn’t just have the ball but chooses to play at a quick pace, with their passing and movement in fifth gear. The defending team will be put under the double pressure of enduring sustained pressure due to the opposition having the ball most of the time, but also having their concentration and positioning constantly tested due to the relentless demands of a flood of attacking waves.

It is interesting that we use the word ‘dictate’ when talking about tempo. It suggests that one team is forcing the other to do something, and they no longer have choice and control.

Yes, the key words here are ‘forced to’ and ‘lack of control’. By dictating the tempo you are naturally enforcing behaviour on the opposition that suits you, not them. If Red team dictate the tempo by controlling the space and gifting Blue Team easy possession, they would find themselves with total possession dominance but little space in which to turn that possession into something penetrative. It could be a case of Red team directly forcing Blue team to do something they lack the players to fully exploit.

The seizing and retaining of tempo, either with or without the ball, is probably the one constant battle throughout the 90 minutes, and yet it is only occasionally and briefly mentioned.

I believe it’s rarely mentioned because the whole nature of this constant battle is actually very subtle and not easily visible. Many fans and commentators are guilty of ‘ball-watching’ and discussing what happens in relation to the ball. It’s easier to focus and comment on what the team and individual players currently in possession are trying to do with the ball. This is logical because how the player is controlling the ball, then how, when, where and to whom he is passing it etc, is plain to see.

But the nature of football is that when one team is in possession and trying to dictate the tempo with the ball, the other is trying to influence the game by controlling the space. And it’s much harder to focus on either the attacking and especially the defensive movement of the players from both teams.

Which is why many people fall into the trap of thinking the ‘better’ team is the one that appears to be trying to do something with the ball. This is not always the case, as the opposition could actually be outplaying them by superbly controlling the space, hence minimising their chances of create something. People are mistaken that ‘outplaying’ is something you only do when the team is in possession. They often forget that football has two states (with and without the ball) and the word ‘outplaying’ can just as easily describe superb defending as sublime attacking.

If the commentator did move their focus away from the ball and onto the tempo, what sorts of activity could they be describing?

They would describe two types of activity. How the attacking team in possession are moving off the ball, and then the way the defending team is trying to prevent them doing this. In short, they would reveal the attacking team’s attacking patterns and the defending team’s defensive patterns.

The defensive patterns are all about how the players are trying to co-ordinate their defensive movement, both in terms of how the attacking players are moving and also how their own team-mates are moving (are there any gaps quickly opening up, hence needing re-positioning to be covered, etc.).

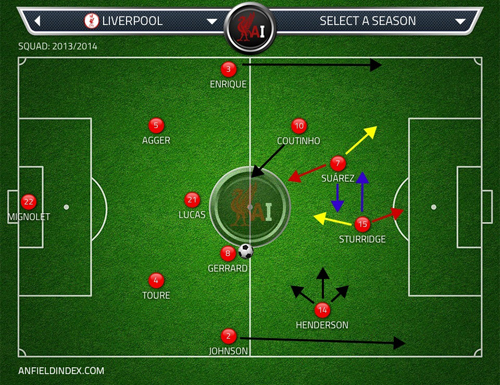

The attacking patterns are all about how the players are relating to each other on and off the ball. Let’s look at these two diagrams which illustrate one of my favourite attacking patterns when Liverpool are playing 4-2-3-1 with Coutinho drifting infield from the left, Suarez and Sturridge playing close to each other, and one of Henderson (from the right) or Gerrard (from deep) available to join the attack late on as the ‘shadow’ attacker.

Initially the team is positioned as a default 4-2-3-1. Wide men patrol the flanks, the double pivot is deep and central, and the front pair are vertically split. Now imagine the ball is coming forward after a period of recycling at the back. Lucas has just collected the ball from the centre-backs and is passing to Gerrard a little further forward. Lucas coming into possession would already have signalled both full-backs to start overlapping, triggering Coutinho to start to move infield and come towards the play, while Henderson is sitting narrower but keeping his position that bit higher and wider.

Meanwhile Suarez and Sturridge are combining with each other in terms of their movement. If one is coming towards the play, the other would start to push on and try to drag the opposition’s back line deeper. Generally it would be Suarez dropping deep and Sturridge trying to sneak in behind. Alternatively we could see Sturridge dropping deep with Suarez drifting wide left, especially if the opposition right-back is now following Coutinho’s movement infield.

So you can see that Gerrard now has several options how to use the ball. He could try to switch the play by feeding one of the overlapping full-backs. He has the option to try and feed the forward looking to break the lines and is obviously trying to sneak in behind. Alternatively he could simply go short and recycle the ball using Lucas and Coutinho.

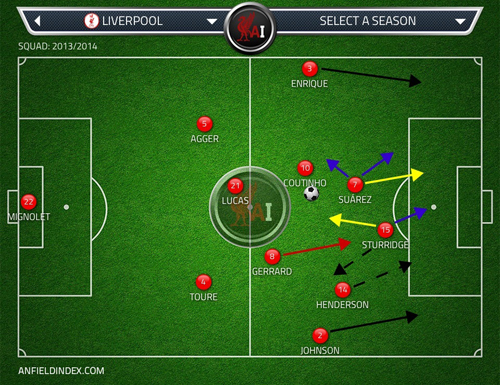

Let’s imagine Gerrard is opting for the recycling option.

He is passing it to Coutinho. Meanwhile the full-backs are already high up, acting as the de-facto width providers. Now Coutinho is on the ball and has several options. He could opt for another series of recycling passes (passing it right to Gerrard, left to Enrique or backwards to Lucas). Or he could opt for something more penetrative, given the off-ball movement of the players surrounding him.

With Coutinho now having the ball centrally and between the lines, the players are expected to provide penetrative runs. Gerrard could start to push on from his deep position. Henderson could sneak in diagonally on the opposition’s blind side. Meanwhile Suarez and Sturridge have already started to roam in a way which means that, no matter where exactly they move, one of them would always be in a position to either receive the ball in a pocket of space or be left 1-on-1 against a defender due to the constant whirlpool of their movement. It’ll be all about Coutinho’s vision and what he decides to do.

The crucial thing is that Liverpool, as a team, all in the same moment, are providing both the stretching effect, enough players threatening off the ball and enough angles for further ball retention if the player on the balls thinks the killer pass is not yet ‘on’.

So instead of ‘Lucas… to Gerrard… to Coutinho…’, a commentator could be saying, ‘Lucas picks up the ball… Johnson and Enrique now stretching out left and right… now Coutinho has it, looking for options…. Sturridge dragging the centre-back with him away from goal…. Henderson and Suarez darting into space… Coutinho tries to feed Suarez…..’

Yes, this would be a much richer tactical explanation of the whole situation. Instead of just ‘ball-watching’ the commentator could choose to be more tactically helpful to the viewers, by opting to expand his comment to include the majority of the tactical actions happening in each situation. This all sounds really simple but so often it’s not even mentioned or seen at all by commentators and fans.

You’ve talked before about the game being played at three speeds – ‘strolling’, ‘jogging’ and ‘sprinting’. Playing at ‘sprinting’ pace is as much about creating those windows of doubt, confusion and hesitation that we talked about before. The aim would be to use each window to create another window of more doubt, confusion and hesitation, and so loosen up the defensive patterns enough to create a clear-cut chance.

Using a ‘sprinting’ speed would, naturally, offer greater opportunity for the team to create quicker attacks built around faster transitions and carrying the ball forward at greater speed. However, while this could end up with the team being able to create several goal-scoring chances, by playing at such high speed their players would mainly be using one or two touch passes, with the players constantly moving all over the pitch. Not only could this mean passes may be misplaced or easily intercepted and attacks break down, but the non-stop, end-to-end actions at such a tempo could lead to players starting to underperform technically (poor first touches, poor passes, poor shoot placement, etc) and mentally (lapses of concentration in defensive and offensive positioning).

For such a quick tempo to lead to a possession-focused approach, the players would not only need to have telepathic understanding and be technicians of the highest order, but they’d also need to possess the physical resources to sustain such dynamic action over sustained periods of time.

Then in contrast, the ‘strolling’ tempo is more useful and suited to providing the right tempo for patient use of the ball, when the team is expected to recycle carefully and move forward gradually as a unit. The players aren’t going to ‘force the issue’ at all. Instead they would patiently work the ball around and wait for the ‘perfect moment’ before attempting that final killer pass to release someone into a good goal-scoring position.

This approach also offers defensive stability. With the team trying to play a controlled and precise brand of football when in possession, it would mean less risk of passes being misplaced or intercepted. With this type of behaviour the players would be expected to move patiently and gradually forward, which means even if the ball is intercepted or misplaced they haven’t left acres of space for the opposition to quickly exploit on the break. All of this means a greatly reduced chance of the opposition being a threat as your team will ‘manipulate’ the game both on and off the ball.

The leap in tempo from ‘strolling’ to ‘sprinting’ is obviously the most surprising and exciting with that sudden surge of energy.

At the same time it is also really demanding. It requires perfect synchronisation between the passer and the mover. It also puts pressure on the player in possession to use his vision, anticipation and decision-making to quickly weigh up all the possible variants and choose the best one. It’s all about the co-operation and cohesion between the players, otherwise such sudden changes of tempo could lead to players simply being caught ‘out of step’. That’s why such things should be a result of specific patterns already ingrained in the players’ thinking.

So these surges of ‘energy’ that switch from ‘jogging’ to ‘sprinting’ pace will go to waste if they are not used in a co-ordinated way, and the play will just become chaotic, and the ‘energy’ evaporates.

Of course! There is no point expending energy for something that doesn’t count as part of a clear strategy and co-ordinated effort. More often than not it is foredoomed to failure. Everything needs to be down to specific patterns with the players knowing well what is expected from them, where and how. Especially when it comes to things they are attempting to do at fast pace, given the risk associated with technical mistakes such as poor first touch, misplaced passes, etc.

In fact it could be said that the ‘strolling’ and ‘sprinting’ speeds are for ‘specialist’ teams in that they naturally lead to certain specific ways of playing (demanding specific skills from the players). The ‘jogging’ speed is then the tempo that is universal. By being neither slow nor quick, ‘jogging’ speed allows both types of play and to switch between them far more smoothly than the other two could. The word ‘jogging’ indicates a state of constant readiness to either slow down or speed up, based on the situation you are in and what you want to achieve in it. At one point you could decide to suddenly shift gears and break forward swiftly. At another you could decide it’s better to slow down the tempo further, draw the opposition toward you, lure them higher, then either go through them or aim to target the space behind them. For a team that does not specialise by being built explicitly around attacking gradually or counter-attacking swiftly, this type of tempo is good as it’s just another part of being a universal team with universal qualities and capabilities.

Fans may mistake this patient ‘jogging’ tempo for a lack of urgency.

Depends on what they understand as ‘urgency’. The obvious way to interpret this word is in connection with a lack of ideas or tempo. If the players are too often simply ‘jogging’ and are not trying anything at all you would say this shows a lack of urgency from a team bereft of ideas. But the other side is to think about whether this slowing down is to allow a constant readiness to quickly change gears. If, from time to time, there are certain moves being tried (sudden switch of play, sudden quicker transitions on and off the ball, etc.), it’ll become clear that the team is executing a very specific strategy of waiting for certain triggers to try and pull off some patterned moves and actions.

Another description of the three tempos could be ‘boiling’, ‘simmering’, ‘cooling’. So a ‘jogging’ tempo is a ‘simmering’ pace that allows the team to easily turn the heat up or take the heat out of the game when it is suits you. So what are some of the key triggers for a team to change gears and turn the heat up or down?

The obvious trigger is based on the first question that the team should ask when they regain the ball – whether the players would look to break forward or prefer to retain the ball. If the situation offers a high enough probability for a dangerous counter-attacking move being developed, the players would be expected to go for it. This will lead to the passing and movement tempo hitting a quicker gear in order for the team to quickly spread out on the break. But if the situation is not ‘on’ then the players would be expected to cool off the tempo, use several back or sideways passes to retain the ball, take a breather and re-start their attacking patterns.

Other triggers are more ‘momentum’ based. For example, when it feels like the team is building some attacking momentum and the opposition is currently psychologically shaken (maybe after conceding a goal, a man being sent off, an injury to key player, etc), the team could decide to suddenly raise the tempo and play with greater intensity both on and off the ball, with the ball and without. The aim would be to use that moment to put increased pressure on the opposition and hopefully grab a goal. The alternative is that your team has just suffered a similar fate, and you are trying to slow down the tempo to give the players a much-needed physical and psychological breather for a few minutes, while trying to keep the opposition at bay.

But as a whole the tempo the team would try to play at is mainly influenced by the strategy that the manager is looking to use. If the manager’s approach involves putting the opposition under pressure right from the start in order to try and score an early goal or two, then the tempo will be quicker with the passing and movement being rapid in order for the team to just ‘fly out of the blocks’ and have wave after wave of attacks towards the opposition. Or if they have the opposite aim of trying to prevent the opposition having the same attacking momentum from the start, looking to control the game with the ball as a sort of reactive strategy, the tempo would logically need to be drastically slower with the players being cautious with their passing and their forward runs, not trying anything risky with or without the ball.

You said that at Barcelona Xavi is the playmaker, setting the tempo, so dictating when and how they will switch from ‘passive’ possession to ‘penetrative’ possession. Can you talk about the connection between the Busquets (controller) role and the Xavi (conductor) role?

It will help to further distinquish Barcelona’s midfield unit in terms of their on-ball roles and contribution. I’d say that Busquets is the recycling playmaker, Xavi is the controlling playmaker, while Iniesta is the incisive playmaker. As each name suggests they are all expected to contribute to how the play is conducted and channelled in every given moment. But the key is that although they are all ball-players, they have different types and levels of creative responsibility within the team’s overall shape, and the midfield unit in particular.

Busquets, as the deepest of the three, is responsible for that initial period when the ball is coming through the defence. He is expected to link the defence and the midfield by collecting the ball from the defenders and initiating the transition phase. He could do that by either feeding one of the overlapping full-backs (who are expected to carry the ball into the opposition’s half) or quickly laying it off to whichever midfielder is coming towards him (usually Xavi).

Alternatively, if the team wants to cool down the tempo or they are being pressed (meaning an immediate pass to the full-backs or the other two midfielders is too risky), Busquests could decide to enter in a recycling phase, using the splitting wide centre-backs to create a 2-1 triangle deep in his half to buy some time and open up a more secure passing angle.

So the ‘Busquests’ role operates largely between the ‘simmering’ and ‘cooling’ speeds.

Then whenever Iniesta is on the ball his role is to be as creative as possible. He has two main ways of doing this. He could either quickly attempt an angled through ball to one of his attacking teammates (especially if he is already near the opposition penalty box). Or he could either run with the ball, going past opposition players before deciding whether to attack the goal himself or lay off a through ball to one of his attacking teammates.

So the ‘Iniesta’ role works mainly between the ‘simmering’ and ‘boiling’ speeds.

When Xavi has the ball his role is to decide when, where and how the transition is going to proceed. That’s why he is called the controlling playmaker. He could think a pass to an advanced full-back is the better choice, so he could feed one of them. Or he could decide that he needs to enter into a recycling phase, using Busquets and Iniesta to create a ‘staggered’ 1-2 triangle (Busquets deep and central, Iniesta as the advanced to his left and Xavi in-between to the right). This will be designed to allow time for the full-backs to push up even higher, the inside forwards to cut infield, and Messi to drop deep to link the team through the middle. Alternatively, Xavi could spot a pocket of space where he could feed one of the attacking players surrounding him. This could be Iniesta who might be pushing forward, Messi who could be dropping deep, or the wide pairs (with the full-backs going on the outside and the inside forward moving infield).

So the ‘Xavi’ role covers all three ‘cooling’, ‘simmering’ and ‘boiling’ speeds. You also said that increasingly in modern football we are seeing the trend of whoever has the ball becomes the playmaker. Do will we now see the whole team have varying degrees of responsibility for setting the tempo?

Yes, of course. It’s becoming common for teams that seek possession dominance to play at least one ball-player in each line. Often we could see teams using at least one ball-playing defender (acting as the de-facto ‘deepest’-lying midfielder). Then we could see the midfield triangle having one deep-lying recycler and a #10 playing as the advanced, incisive playmaker. On top of this we could see at least one of the flanks employing another ball-player in the mould of a wide creator.

All of these players would be expected to provide not only the ability to thread through balls towards the attacking players at any given moment, but also possess that subtle ability to decide the type of tempo their team requires in any given moment. The ball-playing defender and the deepest midfield recycler would have the duty to decide whether the team should try to patiently build from defence or try to deliver searching balls in an attempt to speed up the transitions. Then both the central #10 and the wide creator would be constantly expected to decide whether it’s the moment to attempt that final killer pass, or if another sequence of probing is needed.

So dictating the tempo without the ball will be one of the main options open to a team with less technical expertise and creativity available to them to dominate a game. Presumably by pressing they force the team to move at ‘sprinting’ pace. When they use a ‘conditional press’ they force a ‘jogging’ pace. And when they stand back and hold up they will force a ‘strolling’ pace.

Your assumption is spot on. A team that wants to proactively dictate the tempo without the ball would choose to press the opposition fiercely. This will force a quicker tempo and require both teams to keep up with the intensity or risk being overrun. This is a high risk – high reward approach. By pressing hard the opposition could be forced into mistakes that the team capitalise on by breaking forward. However, the gamble is that such pressing inevitably leaves the team’s shape rather disorganised with plenty of gaps all over the pitch. A good team could bypass these pressing waves and exploit that on the counter.

A team that wants to balance the risk and rewards would surely go for the more intelligent conditional-press. Its intelligence is in that it is selective when, where and how exactly to press, waiting for a situation when there is a higher probability of the ball being regained. This will mean less physical resources are wasted by simply chasing the ball in situations where it is unlikely it can be regained. At the same time it will limit the chance of the team being badly exposed on the break. In essence this is what Liverpool showed in the two home games against WBA and Fulham in 2013-14.

The third variant is the most reactive approach used by team that simply plan to suffocate the opposition for space in and around the ‘hot’ zone. If the defensive organisation is good, and their closing down of the zones and control of the spaces is efficient, it would certainly starve the opposition of space. However, because giving the opposition so much time on the ball is always risky, the key question is can you trust your team to be defensively superb and mentally up to the task for long periods.

The problem is that this type of all-round brilliantly organised and cohesive defensive approach takes time to master. That’s why this is approach that should really only be used by ‘specialist’ teams, those that not only have the players to implement it but either have the background of using such an approach or plan to spend the majority of the training time perfecting it. Asking a generally ball-playing and proactive team to use it is much more of a gamble, given the lack of defensive know-how and natural understanding of this approach that such teams display.

Another intention of dictating a ‘cooling’ tempo will be to eat into the clock and reduce the available time for the opposition to create anything meaningful.

Of course, ‘resting with the ball’ in itself is mainly a defensive approach obviously designed to wind the clock down. It’s a proactive way of being reactive by trying to prevent the opposition having a go at you. The beauty is that if the opposition tries to press fiercely, they’d inevitably leave the chance of their pressing being bypassed and being hit hard on the break. But this is a risk the opposition should take, as at least it gives them some chance to try and seize the initiative back, or at least prevent the team comfortably seeing the game out.

If controlling the tempo is more important than possession dominance, and player movement is more important than what they do with the ball, it is almost as though the ball is no more than a small boat being carried along on this sea of activity.

In a way yes, although even if the ball is not the most key aspect in the game of football it still has crucial importance! After all the aim of the game is to put the ball into the back of the net, while also preventing the opposition doing so. However, tactically the ball is clearly not the most important aspect of the game, although it could be said it’s the feature around which the different defensive and offensive tactics are created.

How much of a game plan can be about timing? So, for example, a team will play in one way with particular aims for 60 minutes, and then switch to playing another way with different aims?

It’s not about ’We’ll play that way up to the 60th minute then completely change it to this way’, it’s about what the actual match context is presenting as a challenge. That’s why the timing of the changes should be based on how the tactical context is changing, or not.

In a way people who say ‘I don’t worry about tactics’ are kidding themselves. ‘No tactics’ is a tactic. It is a choice to not make a choice. That doesn’t mean they choose nothing. It means they choose chaotic random luck.

Yes, something like that. Nobody is saying that tactics alone are everything, or that tactics will guarantee you massive success. Tactics are just one of the major weapons in modern football that the managers can use to gain an advantage before and during every game. There is enough to suggest that without a specific strategy you would not be able to channel your players’ potential into the most efficient way.

When we began talking about tactics I said that I saw the game as occasional high tempo ‘all-action’ episodes surrounded by boring periods when ‘nothing happened’. This will be the ‘strolling’ and ‘jogging’ paced sections. So I now see 90 minutes of action rather than maybe 10 minutes.

So, we could say you are now able to appreciate the ongoing tactical battle more fully. In fact, what you previously saw as the high tempo all-action period is the final piece of the jigsaw. This means that both teams would constantly fight each other tactically attempting to be able to deny each other the chance to create attacking moves but be able to create goal-scoring chances themselves. In a way, such attacking moves are the product of the overall tactical battle between Red team’s attacking patterns and Blue team’s defensive patterns. Previously you were able to see only the ‘concluding’ part, without paying attention to what happened, when and how preceding it or make sense of such situations tactically. In short you are now able to appreciate more parts of the constant ongoing tactical battle between two teams visible in almost every single clash.

Thanks Mihail, see you next time.

The series so far

Introduction – Tactical Blindness

Waiting for kick off – Seeing and observing

0 – 5 mins – To win or not to lose?

11 – 15 mins – The space or the ball

16 – 20 mins – Not Xavi or Iniesta, or even Messi

21 – 25 mins – A new found fluidity

26 – 30 mins – Executed by the feet

31 – 35 mins – Through, over or around?

36 – 40 mins – The main conductor

41 – 45 mins – Let the shape do the work

Half-time – Who Will Blink First?

46 – 50 mins – Tick, tock, tick, tock, tick, tock, Bang!