By Paul Tomkins.

To read Part I: Souness, click here.

To read Part II: Evans, click here.

To read Part III: Houllier, click here.

To read Part IV: Benítez, click here.

(First four parts are for subscribers only. This part is free.)

2010-2015

After just two managers in 12 years – both continentals, who enjoyed remarkable cup success as well as 2nd-place finishes before things turned sour at the end (coinciding with a dip in their transfer success rates) – Liverpool appointed three British bosses in the space of two years.

Roy Hodgson had sole control over his signings in the summer of 2010, although certain executives were perhaps thinking they were suddenly experts when it came to lining up Joe Cole; and then, before Hodgson had a chance to work with the newly-appointed Director of Football once FSG took over, he was sacked. Hodgson had arrived at a time when money was tight, and it shows in his business.

In came Kenny Dalglish at the very start of 2011, in time for perhaps the club’s most remarkable transfer window since the concept was introduced – Suarez and Carroll in, Torres out – although by now it was impossible to say that the manager signed the new players; there were clearly two people involved. Perhaps one of them was keener than the other on certain deals, but both had to be in agreement.

After Dalglish and Comolli were sacked – perhaps in part due to what seemed like some exorbitant fees paid – in came Ulsterman Brendan Rodgers, who was given one window in charge of deals, and when that didn’t work out, a transfer committee was introduced, of which he was just one part.

The committee started with an absolutely brilliant first window, but since then their results have seemed as mixed as they have done for years. Indeed, it’s worth remembering what Dan Kennett termed as Tomkins Law: my conclusion a few years ago that only 40-50% of transfers work out (based on analysing over 2,000 deals). However, at times it seems that the club haven’t even been hitting that basic mark (although “100%” windows like January 2013 are usually going to be outliers).

Of course, perceptions change, with the fluctuation of players’ form. When Dalglish and Comolli were sacked it looked as if Luis Suarez would never be as prolific as he was in Holland, and Jordan Henderson was a peripheral young player, getting a lot of valuable game time, but mostly on the right of midfield.

As tends to happen with Comolli (the same is true of his time at Spurs), some purchases came good later on. It’s worth remembering that this is also true of a lot of Arsene Wenger’s best buys too, and perhaps it’s no coincidence that they worked together at Arsenal. Buying young players with outstanding potential usually leads to a wait for fruition, with no guarantees. But with so many ‘ready made’ older, more expensive buys failing to live up to their pasts following a move, it seems to be the best way forward (unless you can afford to take lots of expensive gambles). In 25 years, almost all of Liverpool’s best signings have been aged 25 or under, with many aged 23 and under. Great signings over the age of 25 really are the exception.

So, how do the signings made by the three most recent managers, the Director of Football and the transfer committee fare?

Initial note: The Transfer Price Index Coefficient (TPIC) is used to assess deals. This rates transfers based on the fee paid, the fee recouped (both in adjusted for TPI inflation) and appearance data, working on the assumption that a successful transfer means that a player makes a high number of starts, or, with his talent spotted by those higher up in the food chain, is sold for a fee that (largely) represents that talent. It is not designed to be infallible – no model is – but it relies on no subjective input, and has been applied to over 2,000 deals. Remember, the deal is what’s being assessed, not the player.

The average TPIC score for a Premier League transfer is 159, and the average number of league games started by any player moving clubs is just 40.

The average percentage of games started by a transferred player is just 37% of those possible, and the average age at the time of a move is 25.6. These figures are based on 2,175 transfers between 1994 and 2014.

In terms of TPIC scores, 36% of deals rate above average (therefore have a score over +159) – which is what I round out to 40% in terms of labelling players successes. (There are a few anomalies in the lower half of the coefficient table – incredibly costly buys who were successes on the pitch, if not the bank – that would take this figure to between 40-50%.)

Only 8.8% of the 2,175 transfers score above +500 in TPIC, which I’d rate as ‘very good’ deals.

And just 1.6% of the 2,175 deals can be ranked as “outstanding”, scoring above +1,000 – that’s just 35 transfers in 20 years. Equally – or conversely – only 39 (1.8%) rank as mega-flops, scoring worse than -200.

All fees will be in 2015 money, unless otherwise stated.

Further notes at the foot of the article.

Notes on this article

As suggested earlier in the piece, I’ve joined Dalglish and Comolli together, and Rodgers’ work is tied up with the transfer committee. We can say that only two signings were definitely down to Rodgers – Borini and Allen – so it’s not worth splitting hairs over.

Also, all as-yet unsold players have a transfer value that is a guesstimate, provided by those on TTT who answered my request (from which an average was taken). It may be that we all overvalue our own players, in what is a tricky task; but there are also cases of undervaluing, such as Daniel Sturridge – in this case, understandably undervalued due to injury (which obviously affects his price tag), but a player who, if he stayed fit for a whole season and played as he has to date, would be worth tens of millions more. Then again, any player is worth what another club will pay, so a market value is merely a guide.

My guess is that players end up being sold for less than you expect, with people like Dirk Kuyt going for just a million due to a daft contract clause, and Glen Johnson leaving for free, as just two examples. But then there are those surprise players who emerge and command a big fee, when you previously didn’t see much worth in them.

While Benítez (three), Dalglish/Comolli (four) and Rodgers/the committee all have unsold players, it’s the latter example where guesstimates have played the biggest part, with 15 of the 17 still at the club at the time of writing. So please bear that in mind.

Roy Hodgson

Never has there been a bigger waste of time in the modern history of Liverpool Football Club. Six players arrived, five of them cheap and old. The other was a mere youngster at 27. They came, they saw – but weren’t often seen – and they left. If ever there was evidence of the false economy of a job-lot of older players, this was it. This was a club treading water by adding lead weights.

Hodgson’s oldies – remember, he had a side that averaged 30 at Fulham (but where that approach was more appropriate) – joined latter Benítez signings like Jovanovic and Kyrgiakos as short-term solutions who solved nothing, although at least Maxi, who arrived six months before Hodgson, bucked the trend. This was a club in stasis, and while it’s unfair to blame aspects of the transfer policy on Hodgson, it’s scary to think of what he might have spent a sizeable war-chest on. His supporters (i.e. fans of other clubs) might argue that he deserved the chance to invest in real talent. Most Liverpool fans beg to differ.

Overview

With the exception of Hodgson, the average price of each manager’s signings, with inflation applied, ranges between £12m-£20m. Hodgson’s cost just £5m apiece.

At the time he boasted that he didn’t need money; that he had shown that he could improve players. Perhaps he couldn’t say anything else (and managers have to sound positive), but it’s one thing organising a mid-table side and another trying to get results at a high-pressure club with players like Paul Konchesky.

Best Buy

Raul Meireles was the only success from Hodgson’s signings, albeit one of the six was a reserve keeper (who, incredibly, briefly found himself as first-choice a few years later). They started under a quarter of the games possible during their stay at the club, averaging just 15 league appearances apiece.

While I never like to remove the successful outliers in transfer analysis – which, to me, would be a bit like looking at someone’s spending on lottery tickets and ignoring the one that won the jackpot – it’s notable that Meireles, surprisingly sold so quickly, helped Hodgson to a “recouped” percentage of 78.9%. Had Meireles not been included it would drop to just 8.8%. That said, his other buys were so cheap, and so old, that they were unlikely to offer much.

(Note: Fabio Aurelio left the club in 2010, and then rejoined.)

Worst Buy

Paul Konchesky. Too old, too mediocre and too expensive (although on Graeme’s database his original fee is listed as cheaper than the £5m I recall, perhaps due to the two youth players Liverpool added to the deal; one of whom, Alex Kačaniklić, has gone on to become a Swedish international.

At least Christian Poulsen was once a good player. But at 30 he was always likely to struggle with the pace of the English game.

Unlucky With …

Joe Cole, perhaps. Cole was a wonderfully gifted player in his early days, but his time at Anfield will be remembered for him regularly being doubled up, gasping for breath. Bob Paisley said that you let players lose their legs on other people’s pitches; at this point in time, Liverpool were doing the exact opposite.

Point of interest

The average age of Roy Hodgson’s purchases was a smidgen under 29. This was neither long-term planning nor a safe pair of hands.

Conclusion

In fairness to Roy Hodgson … Nope, I’ve got nothing.

Oh, go on then. In fairness to him he walked into a dysfunctional club, but then again he knew the score at the outset. His approach was all wrong, and it showed – but in fairness others might also have struggled in the same situation.

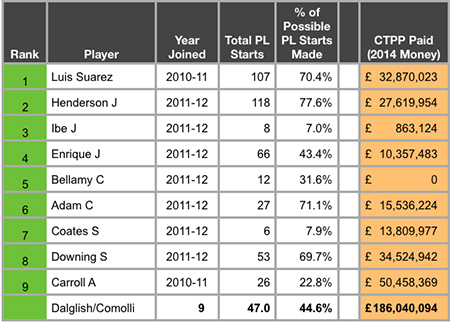

Kenny Dalglish & Damien Comolli

Looking back, Kenny from South Park could have become Liverpool manager in January 2011 and I’d have been pleased. That’s how bad it was under Roy Hodgson, although by this point NESV (now FSG) were in charge, and there was money to spend – much of it from the sale of Fernando Torres, whose offloading would have been much harder to accept under previous ownership and management.

Overview

In many ways the 18 months overseen by Dalglish and Comolli were the most fascinating in terms of transfer policy. It mixed crazy-good with crazy-bad, to provide some incredibly patchy business. But if you can sign a few genuine game-changers, even amidst expensive flops, then you’ll probably be onto something.

Best Buy

Luis Suarez is Liverpool’s best signing in the TPIC table. He also ranks 12th out of the all-Premier League 2,175 deals covered, with a score of +1,365. Despite various bans, he still managed to start 107 league games and leave for a £42m profit in 2015 money.

Suarez wasn’t cheap to start with – the Reds’ 8th-most costly post-1990 signing in 2015 money – and he didn’t stay long enough to start hundreds of games; but he still goes down as a great buy, and arguably the best all-round striker the club has ever had.

Worst Buy

There’s no doubt here that Andy Carroll was the major snafu, with a TPIC score of -537. But more on him in a moment.

Stewart Downing also ranks as a mega-bad deal (scoring -294), having cost £34.5m after inflation, and left for just £6.9m, after 53 league starts. It’s not that he was a terrible player – indeed, at times he could be quietly effective – but that quietness was perhaps the problem: he just didn’t seem cut out for the price tag or the size of club. It’s hard to justify quiet effectiveness when you cost so much money.

He’s another example of a player aged 26 costing too much. It’s a bit like an inverted game of pass-the-parcel, where the prize is something horrible and unpleasant: you don’t want to be the one holding it when the player turns 29, if you have a big transfer fee invested in him.

To pay a lot of money for a 26-year-old (or older) he probably needs to be a level up from Downing (and Adam Lallana). The trouble there is that really proven 26/27/28-year-olds tend to cost a fortune (£60m for Angel Di Maria, aged 26). If they succeed you still make a big loss, and if they fail – as many still do – you’re screwed. Man United can just about shrug off a wasted £60m (or a wasted £20m, plus wages, if they sold him for £40m this summer), but clubs outside the rich three of United, City and Chelsea are less able to do so.

And as shown throughout this series, the number of “proven” Premier League players at that age to have joined Liverpool and flopped is astonishing. Excluding goalkeepers (for whom 28 is still a good age to buy), Liverpool have purchased 43 players aged between 26-30 in the past 25 years, and only three (Dirk Kuyt, Mark Wright and Steve Finnan) have made 70 or more league starts. The most expensive ten after inflation is applied average out at £25m each, and recouped just £9.5m apiece, having made just 45 league starts. (Their average coefficient score is -96, way worse than the average of +159.)

Unlucky With …

Andy Carroll might qualify, were it not for the fact that he wasn’t as professional as you’d expect for a player whose price now works out at £50.5m. He had raw talent, but not the mentality to match; it seemed that he’d never been outside of Newcastle except on the team bus, and maybe a few excursions to Ibiza.

Where I have some sympathy is in the fact that his fee was always going to be Torres-minus-£15m (although this wasn’t something the club had to adhere to; it was a rule they themselves set).

Carroll might have stood a better chance had he cost £15m less, but in hindsight even that kind of pressure would have been too great. On his day he was a joy to behold, but as with all other “on his day” players, those days were too rare.

Point of interest

Just nine signings made by Dalglish and Comolli, and yet a lot of above-average stats on display, both in terms of good and bad. It really was a bonkers time, in the best and worst sense.

Four of the nine – 44% – rate as above average, which is a fair way above the 36% norm across all deals. Two of the nine (22%, Suarez and Henderson) rank as “very good or better”, which is way above the 8.8% league average. This is in part why I feel that Liverpool challenged for the title in 2013/14: with much of the preexisting infrastructure, two highly efficient buys in previous seasons could make a lot of difference once they stepped up to the next level. The reason I highlight this is because it’s actually quite rare. Two ultra-successful signings can make a huge difference, so long as you have some luck with injuries along the way.

One of Dalglish and Comolli’s buys (11.1%, Suarez) ranks as sensational, which is over five times the league expectancy of 1.6%. And it could so easily become two of the nine – Henderson, with 118 league starts so far, would need to make ‘just’ 200 more (a fair amount, mind, but not impossible at his age and given his fitness levels) to qualify as an outstanding deal, even if he was released on a free transfer at the end of his time with the Reds. Or, if he played in the first team for two more seasons and was sold for what he cost (after inflation) he’d also rank as one of the top 1.6% deals, with a score over +1,000. (As a side-note here, TTTers rated his current transfer value at £26.5m, which is actually just below the £27.6m he cost. I think that with prices rising due to the new Sky deal, he’s possibly worth more than £30m, but at the same time it’s not clear which clubs would pay that for him.

And yet having had those excellent stats with four of their signings, two – Carroll and Downing (22%) – rank as terrible deals, which is over eleven times as many as you’d expect to see. Carroll ranks as the 11th-worst signing of the 20 years between 1994 and 2014.

It’s as if it was a high-risk, high-reward approach, with big losses inevitable, but even bigger gains achieved. Unfortunately for Dalglish and Comolli, those gains came mostly after they’d been sacked.

Comolli is certainly an enigma. As with Rafa Benítez, people tend to focus more on his flops (whereas with Arsene Wenger the opposite is true). And yet three of the top 12 TPIC transfers between 1994 and 2014 – Kolo Toure (whom he scouted for Arsenal), Gareth Bale and Luis Suarez – were in some way down to him, including two of the top three. Then there’s Luka Modric, a 4th Comolli signing, ranking 22nd. If his job was to unearth unknowns and undervalued talent, he certainly did that.

Conclusion

The league football became surprisingly dull towards the end of the Dalglish/Comolli era, but the transfers, like the domestic cups, provided their own entertainment. This was easily the most baffling and yet perhaps brilliant period of transfer activity of the past 20 years.

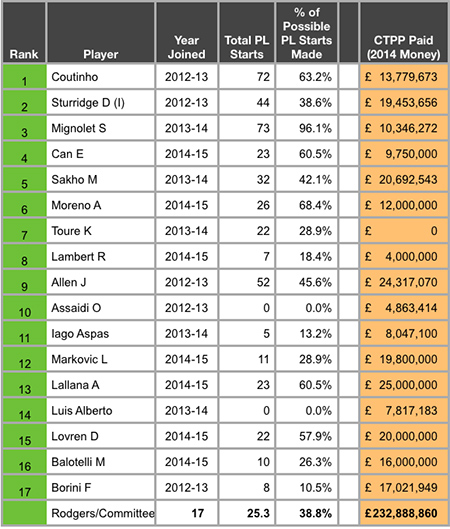

Rodgers and the Committee

The past three years are without doubt the hardest to assess. Not only is a policy of signing young players likely to take time to lead to fruition, but since 2012 there appears to have been several different approaches to recruitment.

With Oussama Assaidi a backroom signing, Nuri Sahin only a loan deal, and Samed Yesil a youth buy who has yet to play in the league, that leaves just Joe Allen and Fabio Borini as clear, undeniable Rodgers signings. This pair don’t reflect particularly brilliantly on the manager’s recruitment skills, and nor does his supposed driving of the Southampton trio last summer. But two definite deals is too few to judge on, and the three arrivals from the Saints must have had some committee input.

If – and it’s a big if – these five were Rodgers’ work alone, then they’d rank as very poor business in the TPIC scheme of things; four with negative scores, and all five well below the average of +159. But this would be unfair, not least because, as part of the transfer committee, the manager has had a say in the successes, too.

Overview

Given the complications involved, all 17 deals included will all go down under the umbrella term of Rodgers/the committee. It’s also pointless including the seven who have already arrived this summer (six new signings plus Origi), because they’ve not had a chance to amass any performance data.

However, somewhat weirdly, the Reds could probably sell all seven right now for a healthy profit. Including Origi, the new additions to the 2015/16 squad have cost £59m (taking Ings’ compensatory fee at £5m); but with Ings and Milner arriving as Bosmans, and Clyne’s fee reduced due to entering the final 12 months of his contract, these could easily be sold for much more. Also, Firminio’s price was helped by the weakness of the Euro against the pound, so that’s another potential saving. I reckon that these seven could now be sold for a combined £84m – not that any of them will leave this summer. Of course, a few bad performances in August and people will be saying that Liverpool overpaid, even for the free transfers.

In terms of current values, the players signed between 2012 and 2014 were rated by TTTers as being worth almost what was paid – and, after inflation, it’s unusual to see potential sale values matching the original price (see Henderson, for example of what I mean, and how the £20m paid now equates to £27m; the TTT panel rated him at just below that in the open market).

But of course, perceptions on ‘worth’ change all the time, and these aren’t the kind of conclusive judgements you can make after a player has been sold. It’s also important to note how young the majority of the signings still are – so if their transfer values are a little overinflated by those who voted, their performance data is harmed by the fact that they’re all still relatively new. Many of these haven’t even had the chance to make more than 38 league starts.

Of course, playing more games means the player has to spend more time at the club; and players over the age of 25 start to lose their transfer value as a result, with the age of 28 where the big dip usually takes place.

Best Buy

In TPIC terms it goes down as Philippe Coutinho – who was just 20 when he joined. The little Brazilian needs to make just 30 Premier League starts this coming season, and to retain the value of £38.9m placed on him by the TTT panel (so, in other words, be as good as last season), to move into the “outstanding” purchase category.

Unless he suffers an unexpected injury, then this seems highly possible – although we cannot yet be totally sure that his performances last season were of a 22-year-old making the kind of giant leap forwards that the best players tend to experience at such an age, or a one-off in terms of consistency. I feel fairly confident that it’s the former, given his incredible youth pedigree – excellent goals-per-game in the Brazilian U17 and U20 sides (so you’d expect him to start maturing at 22) – but as ever with transfers, time can change who we view as success or failures.

Worst Buy

Mario Balotelli and Dejan Lovren are two strong contenders battling it out for the worst buy of the past three seasons. I always think that centre-backs – particularly ones lacking blistering pace – need to be judged after they’ve reached their mid-20s, so I wouldn’t rule out a Lovren revival, especially as he does have a good pedigree. That said, at times his decision-making has been so absolutely bonkers that I’m not filled with any optimism on that front.

However, the worst in the TPIC rankings is Fabio Borini, whose fee now equates to £17m, but who has only started eight league games for the club in three years. He’s currently in the ‘flop’ zone, with a rating of -155 (partly due to a healthy resale estimate of £7.3m), but this is short of the -200 “disaster” zone. However, a fee of at least £5m needs to be recouped to avoid slipping into the bottom category.

Lallana, Markovic, Balotelli and Lovren are four others who could theoretically join Stewart, Cissé, Downing, Aquilini, Carroll and co. as players with a score worse than -200, but after just one year have probably retained enough of their initial value to claw back enough points to escape this ignominy. The problem comes when these players are no longer getting any game time, but also cannot be sold, and, as fringe players for two or three years, their value plummets.

Unlucky With …

There’s no doubt that Daniel Sturridge has been hard hit by injuries. The TTT panel rated him as worth just under £30m, whereas we all know that a fit Sturridge is worth closer to £50m – but a season out injured (and with complicated injuries at that) diminishes his value at this moment in time. Missing the start of this season won’t help, either, as then he’s playing catch-up in terms of match fitness – but it was better to try and solve the problem with an operation than to keep patching him up.

Hopefully he doesn’t become another Owen, Fowler or Rob Jones, whose talents were dimmed by persistent problems – players you always expected to come good again, but whose best football was already behind them at Sturridge’s age.

Fortunately there are plenty of examples of once injury-prone players getting their issues sorted (Gerrard, Giggs, Van Persie, and also I notice, Alberto Aquilini).

Point of interest

Right now, the 17 Rodgers/committee signings (+103) can be said to be a reasonable way below the TPIC average (+159) – with the caveats outlined earlier in this section.

There’s just one transfer which ranks as ‘very good’, (5.8%, as opposed to 8.8%), and just four who rank above average (23.5%, as opposed to 36%).

But most of these figures come from guesstimates as to current value, and that may be adversely affected by the fact that it was such a poor season (which was partly down to those players not performing, but there were other issues too). And to be fair, Coutinho is getting close to being rated an outstanding transfer, and Sturridge should pass the +500 score simply by being fit for most of this coming season.

And so far, this summer’s business seems to make more sense than last year’s, when some good players were bought, but with what seems like a more muddled vision (another expensive left-sided centre-back after Sakho was signed 12 months earlier, and both Markovic and Lallana costing over £20m and yet arguably competing for the same spot in the side). My hunch is that at least a couple of perceived flops will come good this season, but there’s also the risk that someone like Coutinho could suffer injury or loss of form.

Conclusion

With only two of the 17 actually sold at the time of writing, the guesswork involved makes this the least reliable of all this week’s analysis. Many of the players are still under 25, and so we can assume that their best years are probably ahead of them – but this is never a given.

More on how the Rodgers/committee signings compare with other Liverpool managers will be in the final instalment in the series tomorrow, as I make direct comparisons between the seven bosses (plus a Director of Football and a committee).

Notes: reserve goalkeepers who never really played are excluded, as are young hopefuls bought for the youth team and who never made the grade. Loan deals are also exempt, with the player only qualifying if he then joined on a permanent deal.