By Bob Pearce and Mihail Vladimirov.

A 1-2 and a 2-1

TV commentators often present formations as though they are quite simple and fixed, but two teams can play with the same formation and put quite different emphasis on attacking and defending and so look very different.

Of course. Two teams could use the same framework but end up playing in a completely different way. Two teams could use, for example, 4-4-2 but Red team could attack in a possession-based style within 4-2-2-2, and Blue team might look to hit on the break using more of a 4-2-4 (which, to be fair, is more like 6-0-4). Then Red team might look to press by morphing into a 4-2-3-1 shape when out of possession, while Blue team might choose to drop back into a deep 4-4-1-1 shape.

In modern football, given the fluidity, the constant inter-changing and specific ways of behaving during all the phases, teams often end up using combinations of formations. On paper a team could be using a 4-2-3-1, but then they morph into 3-4-3 to attack. Or maybe when they are defending they drop into a flat 4-5-1.

And then this ‘morphing’ capability is increased if the shape is somehow ‘lopsided’. So a ‘lopsided’ 4-2-3-1 could look like they are attacking in a 4-2-4 manner, while also defending in a pure 4-3-3 way.

I’ve heard people say that a good chef can read a recipe and is able to taste the meal. When you see a team listed on paper you must be able to picture the way in which they will play, their strengths, weaknesses, how one player’s abilities are complemented by another’s, and when they are not.

Generally yes, I’m able to do that. But only for managers, teams and players I’m familiar with. So with Premier League clubs for example I’m quite able to foresee the majority of each side’s tactical aspects, compare them against the opposition’s and see where there might be certain areas of strength or weakness. For teams that I know little or nothing about, it’s harder to picture how specifically this manager, with this starting XI, will play. So I’ll need to spend the opening period of the game observing their shape, their basic defensive and offensive patterns, and take it from there.

So you can almost ‘taste the flavour’ of the game. When you look at the two line-ups and formations before a game, what are the key questions you ask?

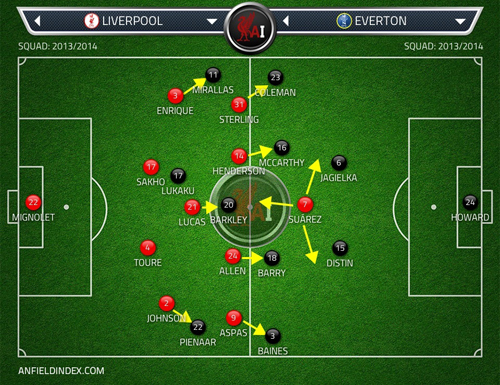

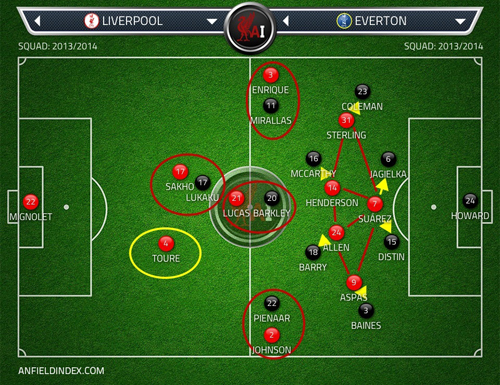

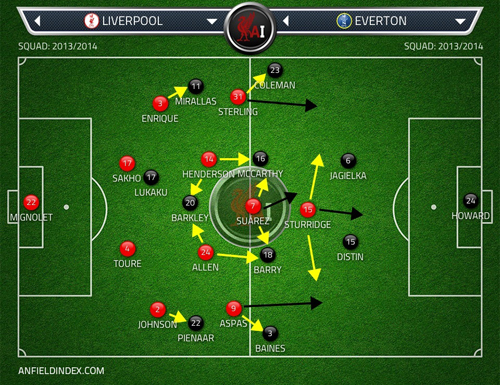

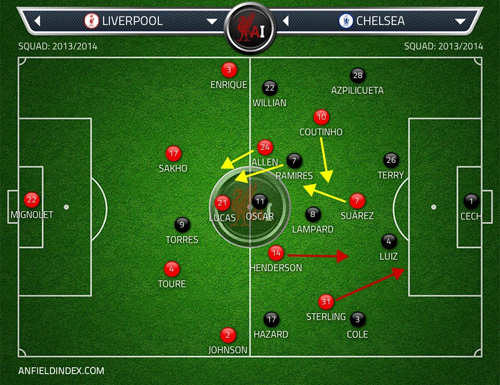

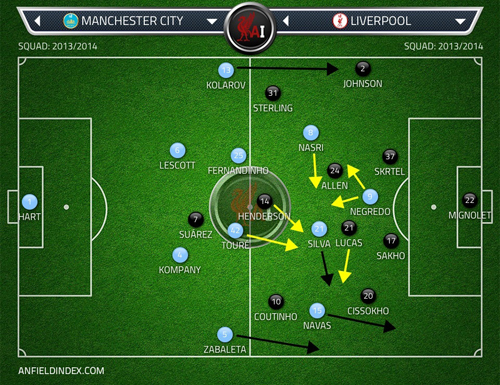

My first question is about what are the potential formations that could be used based on the two starting XIs. From there I start to compare the players within each zone and see whether there might be particular strengths or weaknesses. So one example might be if Coutinho is to play on the left flank, is the opponents’ right full-back well equipped to exploit the fact that the Brazilian is not going to track back efficiently?

Then I start asking myself, given the starting XI and the presumed formations they could use, what are the most likely general tactical patterns you could expect to see from both managers? To use the Coutinho example again, he is usually going to be playing narrow, so will the opposition be easily overrun 3-v-2 or 4-v-3 through the middle? If so, how could Liverpool then exploit that in attack? Will Henderson be able to run through the central channel? Or will we see a more sophisticated pattern with the right winger cutting infield and Henderson drifting wide to maintain the width?

So you’re looking at the the probable arrangements and that is setting off a series of ripples to consider in several directions.

I’m also curious about how the teams will defend. So again one example might be the question of will they press or will they drop deep and stand-off? If I think the opposition is going to press aggressively from higher up, I’d think about whether Liverpool are equipped to bypass this pressure? Or will there be a need to see one of the midfielders dropping towards the centre-backs with Coutinho moving even deeper and narrower to keep up the intended 1-2 or 2-1 midfield shape? What impact is this going to have on how the team is going to attack? If the team needs to create additional passing angles through the middle, will there be a need to see the full-backs pushing forward even more and be outlets to stretch the play and expand the pitch? And so on.

In a midfield trio, you’ve talked about the 1-2 and 2-1 set-up. I am presuming that the three roles of the players in a 1-2 are different from the three roles of the players in a 2-1?

I seriously could write a whole thesis on this subject, so I will try to cut a long story short here. Yes, it’s logical for the roles to be different given that not only are the midfield triangles different but, within each set-up, the zones the players are playing in are different too. However, before I go on, I’d say that the key to truly understanding the differences in the roles within each triangle is to first appreciate the general movements through the phases of the two formations that these midfield triangles are generally used in.

The 1-2 trio is most used within the 4-1-2-3 formation, while the 2-1 variant is a feature of the 4-2-3-1 formation. I really should also just clarify here that, because in modern football there are several alternatives and adaptations on these two basic shapes, I will be talking here about the default versions of the 4-1-2-3 and 4-2-3-1 formations.

The 4-1-2-3 goes through a 2-3-2-3 when trying to build from the back and prepares to transition higher up the pitch to a 3-4-3 shape when this transition is over and the team is now preparing to attack the last third. Meanwhile the 4-2-3-1 has a 4-4-1-1 formation when trying to transition from the back to the midfield and ends up in a sort of 2-4-4 attacking shape.

Based on these descriptions alone, we could easily see that in the 4-1-2-3 formation all of the players have a key role in how the shape is going to transition through the phases. The only ‘static’ players are the centre-backs and the midfield duo. The deepest midfielder, the full-backs, and the front three all have clear positional responsibilities to be moving into different directions for the whole framework to morph as required. Meanwhile back at the 4-2-3-1, the only ‘roaming’ players are the full-backs and the wingers. The rest of the team (centre-backs, central midfielders, split attacking pair) are ‘static’ and largely remain in their initial central positions.

With this in mind it’s easy to see why the 4-1-2-3 is all about fluid movement and triangular interplay between the whole of the team. This leads to a heightened ability to impose a possession-based style of play and a high degree of constant movement interchanging. In contrast the 4-2-3-1 is much more linear as the team interacts not in trios but in pairs (which is logical given the origin of this formation is 4-4-2, where everything is all about the pairs). As a result the 4-2-3-1 shape is much more defensively stable, but less ‘flashy’ in attack.

So does that mean that one midfield trio of 1-2 or 2-1 is more suited to being mostly direct or mainly patient in transitions from defence to attack?

As we follow how the two formations are moving during the different transitions, two things will become increasingly obvious. Firstly, in both shapes the team behaves differently in attack, meaning their attacking units will have quite different roles. So, in the default 4-1-2-3 formation the front three is made up of a roaming centre-forward who drops deep or pulls out wide to join the build-up play, while the wide men will be looking to dart infield. To put it another way, the centre-forward role here is both a finisher and a creator (in fact, probably a 40% f/60% c split), while the wide men are more finishers than creators (60% f/40% c split).

We see this with Suarez and say Sterling.

Meanwhile in the 4-2-3-1 shape the wide men are largely providers with an additional expectation on dropping back behind the ball when out of possession. To compensate for this, the attacking midfielder needs to become the second attacking player (with a 60% f/40% c split) to closely support the centre-forward, who is predominantly a consumer (80% f/20% c).

We saw this with the Torres and Gerrard partnership under Benitez.

Secondly, these different attacking units, and how the general framework moves during the transitions, will have an influence on the midfield triangles.

In the 4-1-2-3, as the team will already have two consumers (the wide men) and one ‘half consumer’ (the roaming centre-forward), the ‘2’ in the 2-1 are mainly playmakers. With the wide men moving infield, the full-backs need to push forward and provide the width, so there is a need for someone to help the centre-backs out and form a solid defensive unit. Hence, during all phases of play, the deepest midfielder role is to always stay behind the play and be in touch with the centre-backs.

In the 4-2-3-1 variant, the main movement fluidity comes from the wide pairs constantly running up and down on the flanks (remember the movement patterns of having a 4-4-1-1 which morphs into 2-4-4). In addition here the advanced midfielder is more of a second forward than a proper third midfielder. With this in mind it’s easy to see why in the 4-2-3-1 formation the midfield duo (the double pivot in the 2-1) are required to stay deeper and largely do the job of the ‘1’ in the 1-2 triangle. Now, because there will be two players doing the job of one, the double pivot will usually have two distinct roles. One of the players is the ball-winner, holding his position, while the other is the ball-player, responsible for dictating the play and pulling the strings from his deeper position.

We saw this with Mascherano and Alonso, again under Benitez.

Now that it is clearer how the different formations function on a basic level, we can begin to delve deeper into the specifics of the differences in the roles of each midfield triangle.

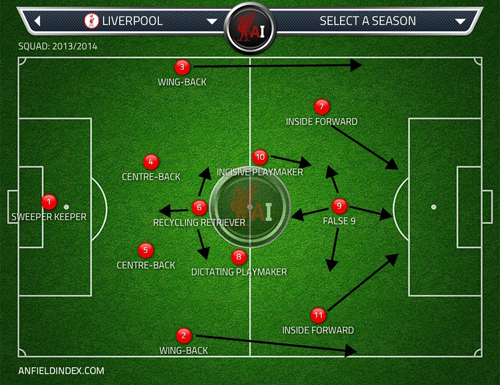

In the 4-1-2-3, the ‘1’ combines the role of the double pivot from the 4-2-3-1 into one and is expected to be both the prime holder and also the one starting the team’s attacks from deep (I like to use the term ‘recycling retriever’ or ‘passing anchor man’ to describe this role). Given that ahead of him the team will have two proper ball-players, he is not expected to be the main assister or chance creator, so his creative responsibility is decreased. He is there to just recycle possession, re-start the team’s attacks, and pass to his more creative team-mates As we have discussed previously, it may sound like his role is very simple, but in actual fact it is crucial.

The duo ahead of him ideally would have two distinct roles of one dictating playmaker and one penetrating playmaker. The dictating playmaker would channel the play, spray passes around and help knit the team together through the middle. To do so he will logically be staying deeper, in between the deepest midfielder and the other more advanced midfielder. The most advanced penetrating playmaker will be the one responsible for linking the midfield and front units. His main job is to provide the incisive passes into the final third.

Barcelona under Guardiola were the best example of what the 4-1-2-3 and in particular the 1-2 triangle is all about. Busquets being the recycling retriever, Xavi the controlling/dictating playmaker and Iniesta the incisive/penetrating playmaker.

The 4-2-3-1 is different in its general emphasis, being more stable defensively, less capable of providing a possession-based framework, and so counting more on quick transitions and the quality of the front quartet (helped out by the overlapping full-backs) to unlock defences. So it’s logical to see the players’ roles here are quite different.

The advanced midfield role is more of a second forward. He starts deeper (from between the lines) but he is looking to either work the channels and free space for the main striker, or surge into the box himself if the striker starts to drift out wide. This, and the fact the wide pairs would be needed to constantly run up and down the flanks (when their team are in or out of possession), means the double pivot is required to do a screening job, always staying a bit deeper and in touch with the centre-backs. But then, given there isn’t anyone to pull the strings from advanced position, there is the need for that split in their duties. I just mentioned that one of them should be capable of pulling the strings and fulfilling the ‘in-between’ role of a dictating playmaker. But in contrast to the dictating playmaker of the 1-2 triangle, here in the 2-1 format this player will just be sitting deeper and closer to his midfield partner. To be able to bridge the gap to the front quartet by pinging long passes and be able to switch the play at any moment, this role requires great vision and an even greater passing range. Meanwhile his partner is the classic ball-winner, protecting the centre-backs, plugging the gaps between the lines, and looking to quickly regain possession and lay it off to his creative midfield partner who can then to start the attacks.

Under Benitez, Liverpool used the 2-1 trio of Mascherano, Alonso and Gerrard, which was the greatest example of the default 4-2-3-1 formation. Mascherano and Alonso as the double pivot, with the former doing the ball-winning and covering tasks, and the latter doing the playmaking and creative part. Gerrard sat ahead of them, starting deeper but always looking for ways to hurt the opposition in and around the penalty box.

Are there tweaks and nuances that can be emphasised in these roles that will give a different ‘flavour’ to either a 1-2 or a 2-1?

First of all I should say that the 2-1 triangle could be used differently. I said that the default 2-1 triangle is the one used within the 4-2-3-1 shape, with a deeper double-pivot and the ‘1’ is used as more of a second forward. But we are now seeing a modern-day adaptation that has the whole midfield unit a bit higher up the pitch with the advanced midfielder sitting deeper and so being more of a third midfielder (a pure #10). Therefore the formation is now more like a 4-2-1-3.

This 4-2-1-3 shape was born out of the wish to have both the stability of a double pivot while also allowing for a possession-based outlook and style of play. Here the 2-1 triangle is far tighter and capable of providing both the required playmaking capabilities and also the necessary additional positional interplay. The double pivot in this formation could be kept as a ball-winner and deep-lying playmaker with the only change being that, instead of a second forward (‘False 10’), there is a proper #10 (i.e. not an attacking but a playmaking advanced midfielder). In this arrangement, because there is no ‘False 10’ to provide that secondary attacking weapon, the wide men would be expected to support at least one of the inside forwards in order to compensate.

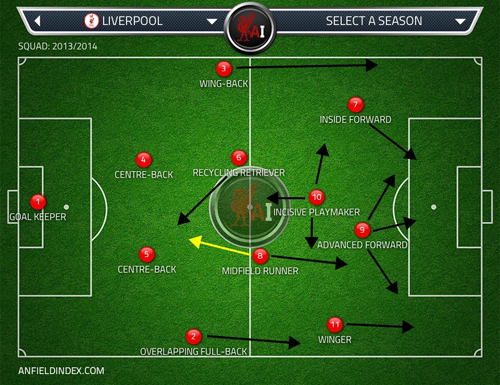

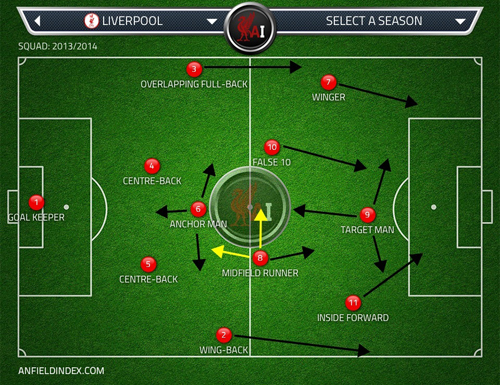

Alternatively, in order to provide a bit more positional interplay through the middle as well as down the flanks, there is the possibility of having a double pivot of a recycler and a midfield runner (box-to-box type of midfielder). The recycler will naturally sit deeper and do the job of the ‘1’ of the 1-2 midfield triangle. This is crucial as in that scenario the double pivot would be sitting further up the pitch, so there is the need for one of them to drop towards the centre-backs and collect the ball to initiate the next phase of play.

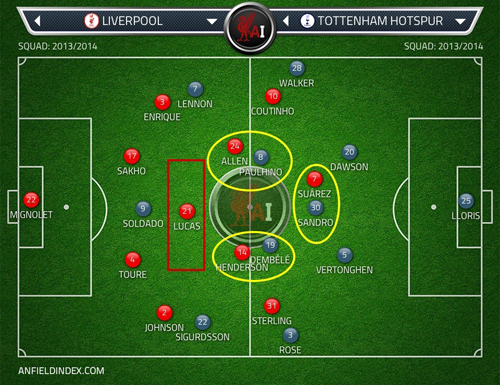

This is largely what Lucas does at Liverpool under Rodgers when he chooses to play with a 4-2-3-1 shape. Meanwhile, the #10 will do the role of the incisive playmaker of the 1-2 triangle. On the ball his main job will be to provide that final pass and transform deep possession into something penetrating in the last third. Off the ball he will either drop deep or drift wide, searching for space to receive the ball and encourage the type of off-ball movement that would inflict positional damage on the opposition. If he drops deep, the midfield runner will be expected to offer the reverse movement, partially to keep the 2-1 midfield shape, but also to provide the secondary attacking threat in terms of surging runs through the middle. In fact you could say he will be doing the job that the ‘False 10’ would do in the default 2-1 triangle. So if he drifts wide, the inside forward would be expected to cut infield to become the secondary penetrating off-ball runner.

In this scenario it is the role of the midfield runner that is arguably the key one. The recycler and the #10 would be more or less specialists, doing their specific jobs. The midfield runner’s role is much harder as he needs to be doing multiple tasks in order to both bridge the gap between them but also do what they won’t be doing. When the recycler drops deep, the runner would be expected to step forward and keep the passing angles intact. If he simply stayed alongside the recycler there won’t be enough angles for the ball to be circulating efficiently, so there would be the need for someone to quickly resort to hitting the front quartet with a long pass. Then, as I said, if the #10 drops deep, the runner will be asked to surge forward.

In defence the runner would be expected to ‘shield’ the recycler by pressing from higher up the pitch, leaving the recycler to just hold his position and plug the gaps between the lines. In attack the runner would often be needed to provide the required runs from deep through the middle in order to break down the packed defence. All of this puts huge pressure on the runner’s tactical and positional awareness, as well as his concentration levels and physical capabilities. To be the non-stop midfield dynamo, always ensuring that he is in position to complement his midfield partners, he will need the pace, power and stamina to maintain his endless running with and without the ball.

For an example of this tactical format look at Mourinho’s Real Madrid. Alonso was doing the recycler job, Ozil had the role of the #10, with Khedira being the midfield runner. Then they had Ronaldo as the inside forward down the left. With such a modern-looking 2-1 midfield triangle, the nature of this shape, coupled with the type of players executing it, meant that Real Madrid were capable of both devastating counter-attacks (as with a true 4-2-3-1 shape) but also passing their way forward using the added fluidity and possession-based focus.

So, given the wider implications of a 1-2 and a 2-1, we would expect to see different overall qualities in the make-up of the team in terms of ‘elements’ like speed, creativity, etc.

Moving on to the 1-2 triangle, one variation is to change how the whole 4-1-2-3 shape is going to function. A good example of this was the Chelsea team in the first Mourinho spell. Earlier we went through Barcelona’s 4-1-2-3 shape, which had a ‘playmaking’ 1-2 triangle. Mourinho and Chelsea offered the alternative of a 4-1-2-3 shape using a ‘physical’ 1-2 triangle with Makelele, Essien and Lampard as the midfielders with Duff, Robben and Drogba as the front three.

In contrast to Barcelona, who tried to pass their way forward, Chelsea put greater emphasis on being able to power their way forward. This was partially because of the differences in the usual tempo that games are played at in the Premier League and La Liga, as well as the contrasting tactical preferences between Mourinho and Guardiola. Chelsea’s main emphasis was on being solid (from both the attacking and the defensive perspectives) and capable of hitting hard on the break, while also being able to literally break down packed defences.

In Drogba Chelsea’s 4-1-2-3 also had a centre-forward who was half creator, half consumer. The difference is that the way he ‘created’ was based on holding-up and shielding the ball, then laying it off to midfield or wide runners. He was often seen dropping deep or drifting wide, doing the job of the creator, either feeding a teammate or at the very least opening up spaces for a runner to surge into. He then would turn and spin in behind and head into the box to execute the other part of his role, the finisher/consumer.

In contrast to Barcelona’s and the default 4-1-2-3, the midfield triangle and the wide men had different roles. For further tactical flexibility in terms of both positional interplay and on-ball activities, Mourinho did not have his team playing with three playmaking midfielders and the two wide men being both inside forwards. Instead he had one of the wingers (Duff) out wide on the touchline, executing the role of the traditional winger, with the other (Robben) either initially staying wider and then moving diagonally to meet the ball near the penalty area, or receiving the ball out wide and dribbling his way infield .

This meant there was the need for the midfield triangle to provide the additional off-ball penetrator, and this was Lampard’s job. He started deeper (alongside his midfield partner, in line with being part of a 1-2 triangle, and not spearheading a 2-1 set up) but often ended up either alongside Drogba, or sometimes even ahead of him. As such it could be said that Lampard executed the role of a proper ‘False 10’ with the difference that he started even deeper, due to being part of a 1-2 rather than a 2-1 midfield set up.

As Chelsea didn’t rely on passing their way forward per se, there was little need for the rest of the midfielders to carry out the roles of a Busquets and a Xavi. Instead Essien executed the role of a proper midfield runner, providing a presence at both ends of the pitch. In attack he offered well-timed late runs to further overload the opposition and catch them by surprise. In defence, as Lampard was often caught out of position (due to the need for him to constantly be surging forward), Essien was often the first wave of pressing through the middle, always safe in the knowledge he had Makelele behind him to cover. Makelele was doing the role of the anchor man, always sitting behind the play, being in touch with the centre-backs and plugging the gaps between the lines. As such his main job was to protect the defence and, having regained the ball, simply but accurately deliver it back to his team-mates

In many ways it could be said that Mourinho’s adaptations of the 4-1-2-3 shape was the perfect mixture of the default 4-1-2-3 and 4-2-3-1. There was a 1-2 triangle with the ‘1’ being always in touch with the defence providing the required calm influence in possession, while there was also a ‘False 10’. But the way in which he diversified the roles of his wide men and the midfield triangle was more akin to the 4-2-1-3 shape in that there was one midfield runner and one of the wide men was always looking to move infield while the other kept the width on the other side. The structure and movement of this adaptation led to a greater number of tactical possibilities and ways of attacking the opposition. With Mourinho being a tactical pragmatist, this would have been vital for him.

Can a 1-2 ever have a two that are both attack-focused?

The only way for a 1-2 triangle to safely support two attacking midfielders is the 3-1-4-2 shape. Having the security of a back three unit which is further anchored by the presence of the ‘1’, means the midfield duo could be freed even more in attack. This is the model Juventus are playing under Conte in the past two years.

So, in fact, the selection of the midfield formation and personnel actually has quite a major influence on the decisions about selections for other positions. We often tend to forget the goalkeeper. Would we see any difference in how they play with a 1-2 and a 2-1?

First of all the way the keeper will play is down to the overall style of play and the philosophy of the manager. For example, for someone like Guardiola, the keeper is an eleventh outfield player. Hence he is asked to be a viable back-pass option and take an active part in the recycling process from the back.

If there is a need to involve the keeper to bypass any pressing in a cultured way (instead of simply ‘launching’ the ball forward), from a theoretical and structure point of view the 4-1-2-3 provides a greater number of passing angles as the centre-backs are often closely supported by the deepest midfielder dropping back between them. So there is often a minimum of a back three unit which can be further helped by the full-backs who might decide to drop in and create a back five if the team is under heavy pressure.

In contrast, the 4-2-3-1 offers less passing angles for the keeper, so for someone like Mourinho or Benitez the keeper is seen more as another deep-lying playmaker, encouraged to use his feet and hands to quickly distribute the ball to the attackers in order to spring swift counter-attacks.

How do 1-2 and 2-1 compare in terms of ability to press successfully?

The answer to that first depends on whether you want to close down or press the opposition, and where you want to do it. If Red team want to close down from higher up the pitch and in triangles, then the 4-1-2-3 shape is more efficient. This is because the front three can be closely supported by the midfield two to produce a ‘closing down unit’ of five players capable of occupying Blue team not necessarily man-for-man but certainly in terms of cutting off their passing angles within the created triangles. Blue team would then be severely tested in terms of their composure and skill on the ball. While it may lead to the closing down waves being bypassed, it might also lead to Blue team being forced into either losing the ball or simply ‘hoofing’ it forward. And even if the wave is bypassed, the back three unit (centre-backs plus deepest midfielder) are there to provide the positional stability and, at the very least, slow down the counter-attack. They would also be greatly helped by the full-backs who would be in position to drop back quickly.

The 4-1-2-3 formation is also very suitable shape if you want to fall back into 4-1-4-1 and flood the centre of the pitch. Having a tight midfield four, anchored by the deepest midfielder, gives you the numbers to initially nullify the space for the opposition to work in with the ball and then, based on the clearly defined triggers, to go on and press hard in order to regain the ball and break forward. This will be especially useful if the opposition is playing with 4-2-3-1 formation as you will mirror them man-for-man in midfield.

In contrast, the 4-2-3-1 shape offers a greater capacity to match the opposition back four man-for-man, meaning there is now scope to go on and press them with the aim of dispossessing them from higher up the pitch. The attacking midfielder (who in most cases will have the responsibilities of a second forward) will push forward level with the main striker and press the centre-backs while the wide men will do the same with the full-backs. This will leave the midfielders and the full-backs in behind in a ‘stand-by’ position. They would be ready, depending on the circumstances, to either join in the pressing wave or stay in covering positions. As such it could be said the team will apply a half-press (press with the front quartet and being ready to close down with the midfield quartet).

In contrast to the 4-1-2-3 formation, the 4-2-3-1 has less capability to create triangles in order to close down or press, as initially it’s only the front quartet doing the pressing work. But this means there is greater stability both through the middle and down the flanks from a defensive point of view. The front quartet presses, the midfield quartet (the central midfielders and the full-backs) covers, while the centre-backs hold the fort at the back.

If you chose to employ a full press you will back up the pressing front quartet with the midfielders and the full-backs occupying the opposition’s midfielders and wingers respectively. But this might leave you too vulnerable on the break if the opposition did manage to bypass the pressing waves.

In a situation where you prefer to drop back into a deep 4-4-1-1 and wait for the opposition to enter your half before you press them, the 4-2-3-1 is suitable because it gives you the natural stability of the two banks of four defensive approach. This will ensure the opposition will be indirectly invited to move forward as there would be no-one pressing or closing them down from higher up. They would be able to spread in attack, pushing on their full-backs and leaving space in behind down the channels and through the middle. Meanwhile having two banks of four would mean your team is solid enough initially to prevent the opposition quickly morphing their possession into something penetrative. Then, again based on clearly defined triggers, the team could start pressing fiercely with the trio in midfield supported by the wide men to create a five-man pressing unit. In contrast to the 4-1-4-1’s shape, the 4-4-1-1’s unit of five pressing players has a midfield quartet and an advanced player, meaning when the ball is regained the team would find it easier to threaten on the break.

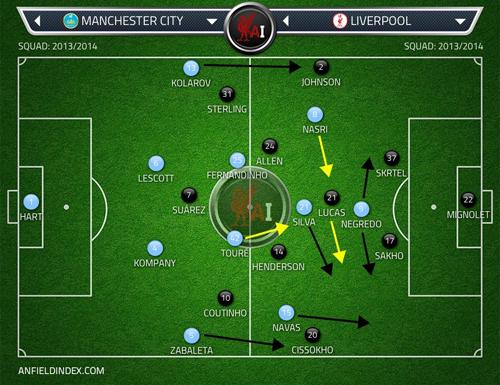

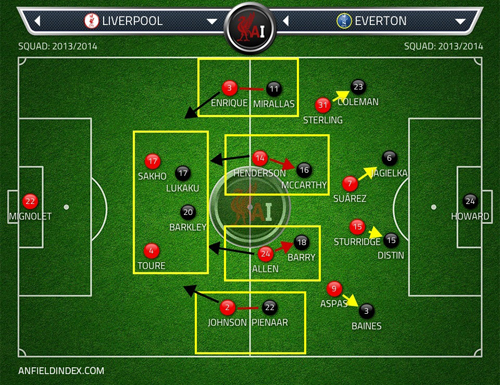

In setting up his team, the manager prepares their formation to deal with their opponent’s threats and exploit their weaknesses. So one option is to match their 1-2 with 2-1, or their 1-2 with 2-1. When would he choose to ‘mirror’ an opponent?

Choosing to mirror the opposition is mainly done for defensive reasons in order to avoid leaving either gaps or an opposition player uncovered through the middle.

Defensively, matching the opponent will mean going man-for-man with their midfielders. This should mean your players are sticking tightly on their opponents and so would be expected to be able to better mark them that way. If Red team have some powerful and/or highly mobile and energetic players mirroring Blue team’s midfield triangle, it really should enable the Red players to press the Blues properly too. You can’t press adequately if you only have one advanced midfielder against two deep-lying players (if you play 2-1 and they 1-2), or one deep-lying against two advanced (if you play 1-2 but they go 1-2).

Being positionally matched leaves less free space, meaning less opportunities to do something in attack. That’s why, from an offensive point of view, the only reason to match the opponents’ midfield triangle is if you plan to employ very specific patterns of play.

So one example of this might be, if Black team is playing with a 1-2 format Sky Blue team might want to start with a 2-1. This will mean the Sky Blue’s advanced player is going to be marked by the Black’s deepest midfielder. But the Sky Blues may ask their player to drag his marker out of position and then have one of their deeper midfielders or one of their wide men surging into the vacated space.

This same ‘drag and pop-up’ strategy could be achieved if Black team play with 2-1 and Red team mirror them with 1-2. The initial aim is to drag the Black’s double pivot out of position. This could be achieved in two main ways.

First, one of the Red’s advanced midfielders could drop in towards his deep-lying colleague and tempt one of the Black’s double pivot to follow him. The resulting space could be then exploited by a Red in-cutting wide man, or by having the Red’s centre-forward dropping deep. Both options will result in Red team now gaining a 2-v-1 advantage over the remaining man in what was Black team’s double pivot. So it’ll be a case of the spare Red man (the now narrow wide man or the deeper forward) receiving the ball and slipping it through for someone attempting a forward run.

Another alternative is for Red team to have both of their advanced midfielders pushing forward and getting closer to Black team’s double pivot. At the same time one of the Red wide men or the centre-forward should aim to get into this zone too in order to create the overloading process (3-v-2). Once this is achieved, the Red player on the ball would pass the ball to someone who at this moment is free and attempting an off-the-ball run.

A manager can also choose to not ‘mirror’ the opposition. Presumably 1-2 v 1-2, or 2-1 v 2-1 would give both sides equal theoretical advantage and risk. When might a manager choose to take this approach?

Yes, on paper, in this scenario both teams would always have a spare man somewhere through the middle. If both managers are going with 1-2 triangles, each team’s deepest midfielder would be the free man. As such that player might be able to dominate the game by having a huge passing influence. This is especially so if he is someone who, like Pirlo, has the required tactical intelligence and nous coupled with the vision and passing range. That’s why in such instances the centre-forward might be asked to drop back onto him and attempt to nullify his influence.

In the scenario when both teams are going with 2-1, it would be a case of their advanced midfielder being outnumbered, so logically it can be expected that the team will be lacking creativity (if that player is a #10), or will not have enough attacking bodies in the last third (if that player is a ‘False 10’). In these circumstances the onus will be on the double pivot to provide the missing element as this is where the spare men will be in these circumstances. It’ll be a case of your deep-lying playmaker being left free to completely boss the game (as often was the case with Alonso during the Benitez years, when so often we saw the opposition make the mistake of concentrating solely on the Gerrard-Torres partnership). Or if you have more of a runner and not a ‘regista’ in your double pivot, your team could gain advantage by this player often catching the opposition by surprise with his late runs off the ball.

So, more often than not, managers choose not to mirror the opposition for defensive reasons. If the opponent is playing with a 2-1 triangle and the ‘1’ is a genuinely dangerous player (no matter if he is a #10 or a false 10 type), the manager might decide having only one player in that zone (as will be the case if he goes with a 1-2 triangle) is too much of a risk. This is because of the possibility of the deepest midfielder being easily overrun or being first dragged out of position and then the free space exploited in the ‘drag and pop-up’ manner. Hence the manager might decide that having a double pivot will provide a greater defensive platform. Having two men between the lines means that, even if one of them is dragged out of position, the other would be there to plug the gaps. Of course, as we just discussed, this is not an ideal solution. It might be a case that the opponents drag one of your deep-lying players out of position, then overrun the one remaining there by having two players targeting him (either a player pushing forward form deep, a forward dropping deep, or a wide man moving infield).

Going to 1-2 when the opponent is also playing with a 1-2 midfield format could also serve as an attempt to solidify your team defensively. The manager might plan to have his ‘2’ sticking tight on their ‘2’ and have the ‘1’ as the spare and covering player. However, the risk here is twofold. Firstly, this will mean the opposition’s deepest midfielder will be left unmarked (unless your forward drops back onto him when out of possession). Then secondly, the opposition could overload your deepest midfielder by having either of the wide men cut infield between the lines, or have one of them cut infield with the centre-forward dropping between the lines.

But if we are to focus solely on how a 1-2 triangle could be covered it’s by having yourself a 1-2 shape with the ‘2’ being the man-markers and the ‘1’ providing the zonal cover, in addition to your forward dropping back onto their ‘1’.

From an attacking point of view, choosing to not mirror the opposition’s midfield triangle will have certain benefits. But again, this will only be the case if there are specific movement patterns designed to get the best from your spare man (wherever and whoever he might be). So, as we just said, if Blue team is playing with 2-1 Red team could also start with 2-1 and use the ‘drag and pop-up’ strategies to get the better of them. If Blue team start with 1-2 then Red team could also choose to start with 1-2, but it might be a case that their front three are required to participate heavily in order to secure them a spare men and first drag the Blue’s deepest midfielder out of position and then exploit the vacated space.

As we said at the start, the nature of the 4-1-2-3 shape is to see the forward being also a creator, so the common strategy is to have him dropping deep and looking to pick up the ball and then feed one of the in-cutting wide men. But currently we are increasingly witnessing the growing use of an alternative strategy. One of the Red’s wide men moving infield (especially if he is more of a wide creator) to occupy the Blue’s deepest midfielder, with the centre-forward working the channels and the other wide men attempting diagonal runs off the ball. Again, it’s all about first dragging the opponent and creating free space and then exploiting it as dangerously as possible.

Presumably a manager could switch the midfield trio back and forth (even with the same three players). When would be the circumstances, and what would be the triggers, when they’d look to switch from 1-2 to 2-1, and from 1-2 to 2-1 during a game?

The manager will want to either match or not mirror the opposition for all the possible reasons we just talked about. But at some stage in the game there is the possibility that he finds that his initial plans are not working, either from an offensive point of view or because the opposition are getting the better of his chosen defensive strategy. So it’ll be a case of the manager assessing the context and then deciding how to re-adjust based on the way in which his team are struggling or where and how the opposition are enjoying success at this time.

We talked about how if the Red team’s advanced midfielder (in 2-1) is getting the better of Blue team’s deepest midfielder (in 1-2) and from there Blue team are being easily picked apart. So the Blues could decide to solidify their team by switching from 1-2 to 2-1 and have the security of another player sitting between the lines.

The other scenario is that if Red team start with 2-1 but find that Blue team’s double pivot are completely dictating the play (one of them spraying passes, or the other constantly making dangerous runs – or both!), the Reds might want to switch to 1-2 and have their ‘2’ sticking tight on the Blue’s double pivot and pressing them hard. This should now leave the Blue’s passer with far less time on the ball, and the runner being picked earlier before he manages to pick up speed or is entering into the last third completely unchecked.

In attack it might be a case of Red team’s 2-1 struggling to break down Blue team’s 1-2 as the Reds struggled to execute the ‘drag and pop-up’ strategies or that the Blue’s players are very disciplined and solid defensively. So the Red’s manager might then decide to try and flip the triangle to now have a 1-2 triangle with the aim of then having the two advanced midfielders trying to overload the Blues between the lines, using the wide men to concentrate on stretching the play and keeping their full-backs busy and so unable to tuck infield and help out centrally.

Or, if Blue team starts with 2-1 and Red team with 1-2, if the Red’s previous strategy of having two advanced players and wingers stretching the play is not proving effective, they might want to now mirror Blue team and go with a 2-1 in order to have a free runner arriving from deep.

We’ve talked about diversity and variations, but what are the consequences of a midfield unit lacking variety?

In short, the midfield will be ‘flat’. This means the whole unit will lack diversity in their ‘on the ball’ actions, and also in terms of their movement. All of the players will be doing much the same things on and off the ball, which will mean they are overlapping their duties and causing more harm than benefit to each other, and the team as a whole. In modern football, which is so fluid, you can’t have even two players doing exactly the same job, no matter where they are playing. The effect will be as though you are playing with one (or more) man down.

There may perhaps be very specific scenarios when you can afford to have some level of overlapping in the midfielders’ roles. One example might be if you are playing 4-4-2 against three-man midfield and your main strategy is to suffocate them for space, playing two extremely deep banks of four and hoping to hit them on the break. Here you could want your two midfielders to be pure destroyers, sitting ahead of the defence and breaking up their attacks. So the lack of variety will be less of an issue from a defensive point of view. Still you’d like one of them to be more creative and with sufficient passing abilities and range to allow them like to be feeding your forwards one way or another. So even a certain degree of variety/diversity is always required.

When we first began talking about tactics it was easy to wonder if you were just talking in riddles, because each time I thought I understood something and made a comment, you’d say ‘Yes but that doesn’t work here’. At best this sounded evasive, and at worst it sounded like you were just making it up on the spot. The more we have talked, the more I can see that there are no simple answers with tactics because so much is about achieving a balance. And, because everything depends on everything else, one small tweak, change, or repair ‘here’ will have consequences ‘everywhere’ else.

So now I appreciate that there is no so-called ‘best’ XI, no ‘best’ formation, and no ‘best’ player. There is one game at a time, with each one being a constantly changing dynamic situation, with many moments of possibility, that requires pragmatic decisions which take into account as much of the whole picture as possible. People use the phrase ‘square peg in a round hole’, and with tactics it seems like game by game the coach has to try to work out the shape of the holes (as those holes continue to constantly change shape), and be finding pegs that fit these ever-changing shapes.

So I see that some of my questions were maybe one dimensional, and that when you try to answer you are having to include multi-dimensional considerations. It is not a simple cause and simple effect situation, it is far more about complex influences and complex consequences.

Precisely. That’s why here in our conversations, or in the articles I’ve written analysing matches, I’ve always tried to be as detailed as possible. There are some overlaps and some templates that could be used against certain types of opponents when you would expect them to do more or less the same thing. So, for example it’s easy to foresee that teams like Stoke, West Ham, WBA, Sunderland, and Norwich are all going to just ‘park the bus’ at Anfield. So, more or less, you will need a very similar approach against all of them.

But there are matches that are going to present different challenges and will demand different solutions. That’s why tactical management is all about taking each individual game in isolation, and preparing for it with different emphasis and aspects.

Modern football is now extremely tactically fluid, which means that the context is going to be changing, not simply on a match by match basis, but also within each game. You can’t just prepare your team to simply go out and boss the game and look to outplay the opposition. There are plenty of things that might change, as a result of what is presented by the opposition and what is working or not for your team. This will all need your attention and tactical management ‘live’ during the game.

Thanks Mihail, see you next time.

The series so far

Introduction – Tactical Blindness

Waiting for kick off – Seeing and observing

0 – 5 mins – To win or not to lose?

11 – 15 mins – The space or the ball

16 – 20 mins – Not Xavi or Iniesta, or even Messi

21 – 25 mins – A new found fluidity

26 – 30 mins – Executed by the feet

31 – 35 mins – Through, over or around?

36 – 40 mins – The main conductor

41 – 45 mins – Let the shape do the work

Half-time – Who Will Blink First?

46 – 50 mins – Tick, tock, tick, tock, tick, tock, Bang!