So, what’s going wrong at Liverpool? I left the house this morning for the first time in a month, to collect some supplies, and it was the question I was asked. Standing in the snow, it was a matter of “how long have you got?”

To make this free-to-all piece easier to digest, I’ve written it mostly as bullet-points, after this extended introduction. As the title suggests, these are not the only issues. And as ever, these are my best guesses, and some may be as off-target as the Reds’ finishing in much of January.

Most of it was written before the defeat at Old Trafford, but to me that proved a good performance – and it should to everyone else – in a game where many of the Reds’ qualities returned. There were lovely long passes from flank-to-flank by the full-backs (missing for some time) with Trent Alexander-Arnold’s passing much better than of late. There were four big chances created, two good finishes – and one of the main points I was revisiting, and that I will leave in the piece, was Mo Salah’s refusal to use his right foot. Suddenly he had two shots in the same game with it, and scored a lovely goal, before adding a second with his left. There was not a succession of poor crosses, one after the other.

As Jürgen Klopp said after the game, it wasn’t perfect, but there were a lot of steps in the right direction. Liverpool had as many shots as United, as many shots on target, as many big chances, and more possession, while United – a highly dangerous counterattacking team – went into the game in top form, at home, against Liverpool in a slump. United’s three used subs alone cost over £150m, which was getting close to the cost of the Reds’ starting XI, while United started with two players who cost £170m combined (before inflation is applied).

As I said on the site after yesterday’s game, if people can’t see that it was a good performance, then I genuinely worry about what people are seeing. The xG scoreline ended roughly 2-2 (with the Reds a fraction ahead), and yet Liverpool had the greater difficulties going into the game. And if people can’t respect that this is a good United side, then that’s a worry too; I had my doubts in the summer, and early in the season, but they deserve to be taken seriously. Their football is not the most sophisticated, but they defend with numbers, they have some serious heft, and they break at exceptional pace. (They’re also not suffering an injury crisis, which helps.)

So hopefully the list of issues I raise in this piece are on their way to being solved, but some of them can’t be, due to injuries.

I have also published a couple of articles recently that cover other points, or where I started to form the arguments I expand on here. The first was on New Year’s Day, after a couple of poor displays, and the second was a couple of weeks later.

People can talk about things like Liverpool, or Klopp, “being found out”, but when there are so many altered variables, it’s much harder to discern things like tactics. After all, when injuries, illness, insufficient preseason, an unusually packed schedule and refereeing/VAR weirdness coincides with freakishly bad finishing (that is not representative of the 3-4 years the same strikers have just delivered), is that a team being “found out” or just a run of insane bad luck?

In The Athletic last week, Raphael Honigstein wrote an excellent comparison with Dortmund’s struggles in Klopp’s final season in Germany. There were a ton of similarities: injuries and absentees; players not having a proper preseason; individual errors; and poor finishing (or one thing that could be added about this season: keepers playing a blinder, as Liverpool have seen in January when finally producing great efforts). But the underlying numbers were good at Dortmund; it was often bad luck and narrow margins. And the underlying numbers, while not everything, are always worth considering.

Referring to the Dortmund players who arrived back late after Germany won the World Cup, Honigstein noted: “A … lack of freshness could be detected in the group of fellow Germany internationals who had missed out on a proper pre-season.”

But back then, people even questioned Klopp’s style of play, as if it were limited. Maybe it was a little less three-dimensional back then, it’s fair to say that his approach, which took Dortmund to a record German points tally, a title defence and a Champions League final, was not shabby; and that it has developed in the six years since.

Dortmund had been going full-tilt for three years, to overachieve, just as Liverpool have; and while I felt this Liverpool team could actually improve this season, given its average age (no melters) and the additions, that did not take into account the lack of preseason, limited training time, massive injury list, bonkers VAR decisions, still no fans at games, and maybe the team just hitting the wall in terms of effort and possibly hunger (the last of which is always a potential issue after everything has been won, and it must be harder to rouse yourself when the football feels somehow “fake”. Perhaps when things are going well, the lack of fans isn’t as noticeable, but the games feel odd when you are struggling).

Since 2015, Klopp’s approach has developed massively, with the assistance of Pepijn Lijnders, to help the Reds evolve into a highly-efficient and varied passing team, and not a team that’s only about gegenpressing. Liverpool regularly found the ammunition to beat low-block sides. You don’t rack up 97 and 99 points whilst becoming champions of Europe and the world if you can’t play an incredibly rounded form of football, and overcome all types of opposition. But obviously this is not that same Liverpool side right now, as it lacks many of those players, and those who are playing are not always fit or full of energy.

Liverpool’s choice of playing an extremely high line earlier in the season, and reverting to a less-high line more recently, may have contributed to different tactical issues and weaknesses (each option has pros and cons), but even when Liverpool lost 7-2 at Villa, it was a 3-2 game on chances, with no Alisson. In goal was Adrian – who was vital in Liverpool winning the league last season, before his form dipped – but who no longer looked fit to stand in for Alisson (and who gifted Villa an early goal).

Adrian was a great sticking plaster in 2019, but he is not an elite keeper (and was never expected to be), and at 34 is past his best. Once his confidence took a hit late last season, the writing was on the wall. It remains a great bit of business, given the victories in all eleven of his league games last season as a free transfer, but as with 5th and 6th choice centre-backs, you can’t judge a team when it includes someone who has (now) become the 3rd-choice keeper. (At least Liverpool didn’t pay £72m for a Spanish keeper who, due to poor form and pressure, doesn’t even seem to be able to catch a football right now.)

Liverpool have been exceptionally good for several seasons now: Champions League final, reached in incredible fashion; Champions League winners, 97 league points; Premier League champions with 99 points. A valid worry would be that after three hectic and emotional seasons, the team might hit the wall. It wouldn’t be the first time it’s happened to a great side. But so much other stuff has happened, to make this a freakish campaign. Defending a title is hard, but not team has ever had to defend it without its own crowd.

I don’t believe that this is the start of some type of decline. But also, that’s just my hunch – and it doesn’t mean that it is not the start of some bigger decline, either; what goes up must come down at some point, after all. But as with Dortmund in 2014/15, when they were bottom at the halfway stage, the underlying numbers suggest the team is better than the results they are getting.

The new players added to provide freshness and new dimensions have often been injured, as have several other key players. We heard all last season how the absence of Aymeric Laporte was the reason Man City struggled, but they also played plenty of games with John Stones and Nicolas Otamendi on the bench, unused. They had centre-backs, they just didn’t rate them. Laporte can’t even get in the City team this season, so he’s no Virgil van Dijk, is he? Yet Liverpool have also lost Joe Gomez for the season, and Joel Matip has missed a ton of games.

It’s a little disconcerting that Klopp has stated he wanted a new centre-back but that there are no funds for one, yet this should be no surprise, even to him, given that since Covid struck at clubs started losing in excess of £100m in a year.

After a difficult and unconvincing start, FSG have run the club brilliantly – anyone who doubts that after the success of the past few years (whilst improving Anfield and building a new world-class training complex) is insane – but Covid is a spanner in the works that no one foresaw a year ago. The loosening of FFP has allowed the petrodollar-backed clubs to speculate to accumulate, but the FSG model, which is the soundest and most honest, is to not take any money out of the club, and to put all money received back into the team. But this has been done in the form of a massively increased wage bill, and not just transfer outlay.

Wage bills are easily overlooked, but they almost always cost much more per season than any transfer outlay; and you can be committed to paying players for several more years, when your income suddenly drops, and some of them may not want to leave to free up their wages for someone new. You can write in bonus clauses to offset losses like not qualifying for the Champions League, but no one factored in Covid.

The club is in an unstable and unexpected financial position, and as such, it cannot easily give new contracts or commit to increasing the wage bill without knowing when the income that foots the salaries will return to normal. In addition to losing millions per game in match-day income, clubs had to pay back TV money last season, and may have to do the same this season.

Either way, Liverpool, like many other clubs, are haemorrhaging money (but unlike some other clubs, they do at least try and balance the books as the essence off the business model), and are trying to work out when things will get back to normal. Younger fans may not remember how Leeds budgeted to be a Champions League club 20 years ago, overspent massively, failed to qualify again, and, somehow managing to avoid going out of existence (after selling virtually all their players), spent 15 years in the wilderness. Liverpool not making the Champions League will be a big blow, but it won’t cripple the club, as long as Covid doesn’t continue to keep fans out of stadiums.

And of course, Liverpool’s bigger wage bill is linked to clauses that pay big bonuses for success. But last season, the prize money was reduced via repaying part of the TV deal, and the millions generated on matchdays was always part of the equation, with packed houses when doing well. (It could be a clever ploy by the players to be less successful this season, to save the club some money. Perhaps, good people that they are, the referees are also doing the same, to help the club out of a financial hole.)

Anyway, after that long preamble, here are a series of bullet-points of issues that I think are playing a role in the slump:

INJURIES/FITNESS/ROOKIES

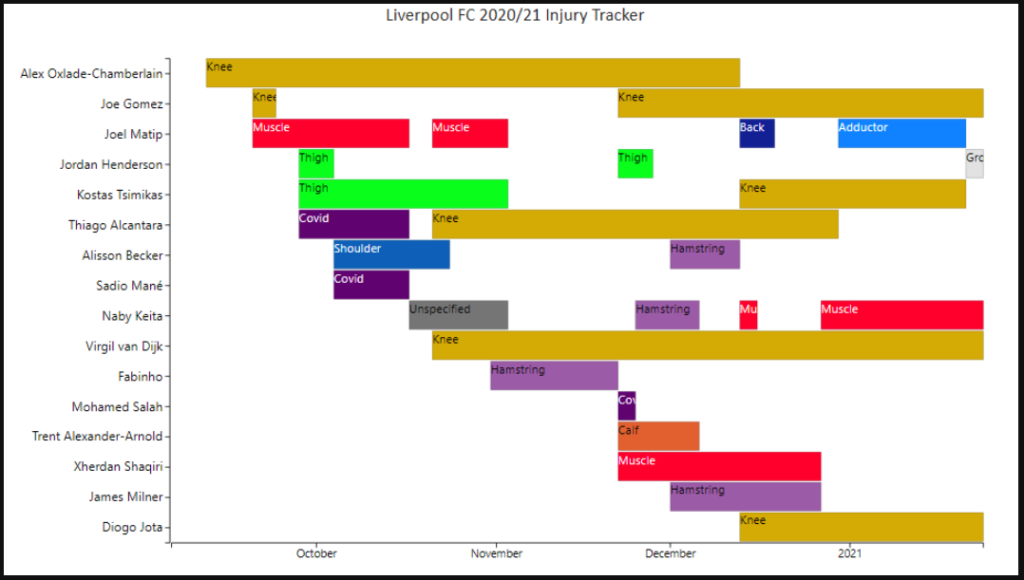

- Liverpool are averaging 5.8 absent players to injury or illness this season. They started the season at around four injuries per game, but it’s often been up or above eight. Often the players injured have been undeniably world-class or amongst the key men. Andrew Beasley’s graphic for TTT is worth repeating here, just to show, visually, how bad the injuries have been.

- Liverpool have used 14 centre-back pairings this season. That alone, caused almost entirely by injuries, shows the chaos and lack of consistency at the back. Uncertainty at the back can spread to the rest of the team. No department of a team operates in a vacuum. Teams that struggle to defend put pressure on their own strikers, and vice versa. Liverpool’s striking struggles actually began when Joel Matip went off in the first-half against West Brom – for the next few games, the midfield was doing more work protecting the stand-in centre-backs, who were defending deeper and at times uncertain on the ball (particularly the honest but limited Nat Phillips at Newcastle). Then a slight slump became a rut.

- Liverpool’s teenagers are not good enough … yet. The Reds’ Premier League campaign has seen almost 1,000 minutes played by teenagers. Add reserve goalkeepers (one of whom had never played a league game before) and the older but still inexperienced Nat Phillips, who was due to be sold to the Championship in the summer, and it’s over 1,500 minutes for players you would not expect to see in the team this season, or even on the bench in many cases. Combined, Virgil van Dijk, Diogo Jota, Thiago, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain and Naby Keita have played just over 1,800 minutes, so not much more than the players who might be ranked 20-25 in terms of pecking order. Add a sixth player, Kostas Tsimikas, a new signing brought it to enable the manager to rest Andy Robertson here and there, and … it’s still just over 1,800 minutes.

- Rhys Williams is a very good 19-year-old centre-back. But all young centre-backs make mistakes, and Williams does not have the pace that helps most young centre-backs recover. Williams is also not yet bulky enough, but he’ll fill out. I always say that Slow Giants rarely flourish before the age of 25, because they need so much experience and knowledge to position themselves better, as seen with Sami Hyypia (who was rejected by Oldham aged 21), and to get stronger in the air. Hyypia was moved to a holding midfielder in Holland, and Matip spent time as a holding midfielder in Germany. Jamie Carragher was shunted out to full-back until he was in his mid-20s, although you can’t really do that with centre-backs these days if you want to be an attacking side. Even tall young centre-backs can get knocked about by wily old pros built like boxers, and their aerial-duel win percentages tend to improve greatly with age, too. With Jordan Henderson now a centre-back reserve, Williams is essentially the 6th-choice, Phillips 7th choice. (As soon as Henderson dropped into defence he caught the curse, and he got injured too.)

- Curtis Jones is an excellent 19-year-old. But … he’s 19. Like Williams and, er, Williams, he’s a rookie, learning on the job. You’ll never get perfection from teenagers, unless they are destined to be the world’s elite players; and usually that means they are playing up front. And even elite young strikers miss loads of chances, give the ball away and fail to read the game as well as older players. For young centre-backs and goalkeepers, mistakes get magnified ten-fold.

- Jürgen Klopp’s teams are all about energy and passion, allied to increasing skill and guile. The lack of fans at games coincided pretty much with the Reds’ collapse in form last season, although the league was quickly sewn up. It feels like the extra energy is lacking.

- With no proper preseason, and several players coming back obviously rusty after long layoffs, the Reds are clearly not as fit as in previous seasons. Unlike some other teams, fitness is a huge part of Liverpool’s DNA under Klopp. And now they cannot play on the passion of the crowd, which was a big part of Klopp’s magic: he took a nervous Anfield in 2015 and made them more vocal again, less edgy. Even now, Liverpool have not lost a league game at Anfield in front of a crowd for nearly four years. It’s four days since they lost in an empty Anfield. Klopp looks a little lost – unable to rouse the absent 12th man, his team lacking their usual energy. It’s been an exhausting and emotional few years, and it’s a well noted psychological phenomenon that sportspeople can suffer a kind of depression after reaching all their goals, because they lose the thing they’ve been chasing.

- In some ways the season reminiscent of Chelsea’s collapse in Jose Mourinho’s second spell, when he never felt that they were fit from the start. He called them “undercooked”. The difference, of course, is that Mourinho alienated players and staff, and made the atmosphere toxic, as he had at previous clubs and subsequent clubs (but not yet Spurs). Klopp has never done that at any club since he started at Mainz in 2001. He will never let a mood get that low and poisonous, and indeed, turned it around at Dortmund to produce top-four form after the winter break, which took them from joint-bottom up to 7th.

- Using that analogy, Liverpool started the season undercooked, and being cooked was a big part of the Liverpool’s games: hard pressing, running off the ball, being strong and unrelenting late in games. It no longer feels like the Reds are ending the games in the way they they did for the previous 24 months. Some players, like Thiago, Alex-Oxlade Chamberlain, Xherdan Shaqiri, remain undercooked, after months out. Others, like Gini Wijnaldum and Andy Robertson, and the front three since the injury to Diogo Jota, are probably playing too often. There is no midwinter warm-weather training camp that Klopp used in early 2015 to rouse Dortmund, the like of which Liverpool benefitted from in 2019 and 2020 (even if the immediate results weren’t always great, it helped with long-term refreshment, and in 2019 in particular, Liverpool won their final nine Premier League games as well as the Champions League, after playing Bayern, Porto and Barcelona twice each in that same spell).

SERIOUS SET-PIECE REVERSAL

- Virgil van Dijk as an attacking threat at set-pieces is vital, as the Reds can win a lot of corners against low-block opponents who are forced to head or clear behind. While teams then often block-off van Dijk illegally to a baffling lack of VAR intervention, sometimes it takes three men to stop him, and he can become a decoy. If you also have Joel Matip in the box, that makes for another elite aerial player to mark – he’s not quite as good as van Dijk in terms of timing headers, but he’s taller. Then, add Fabinho, Jordan Henderson and Roberto Firmino, and that makes five players capable of scoring headers from corners, and then, if the delivery is right and space opens up, Sadio Mané makes a sixth. But the very presence of van Dijk and Matip often open up that space.

- Van Dijk and Matip are vital, as otherwise Liverpool are a small team. Moving the two biggest midfielders to centre-back helped the Reds to stop leaking goals, but it took away height from the team. Liverpool’s outfield lineup against Manchester United averaged below 5’10”, which is tiny for a Premier League side – about as small as any side I’ve analysed in over five years of checking these things; by contrast, United’s was over 6ft, and they could actually field an almost first-choice XI (adding Edison Cavani and Nemanja Matic) that averages over 6’1″. That’s positively Pulisly Stoke. Man City have improved defensively since reverting to centre-backs who are at least 6’2” and having a big holding midfielder. They’re still not a tall side overall, but they are taller than they were, which was about as tall as Liverpool have been in recent weeks. One of Liverpool’s big advantages over City was the aerial dominance, and injuries have cost the Reds that.

- According to Andrew Beasley, the Reds – despite still somehow (for now) being the league’s top scorers – rank just 8th for set-piece goals scored, with six. But two of those came on the opening day, one via a familiar van Dijk thumping header.

- Liverpool have played nine league games (seven full matches and two partial matches) this season with neither Matip nor van Dijk. In other words, half the season. In those games that both missed, the Reds have scored just one single set-piece goal: Roberto Firmino’s versus Spurs. That would extrapolate to a paltry four goals a season.

- By super-stark contrast, last season the Reds ranked top with 17 set-piece goals, and ranked in the top four for fewest set-piece goals conceded (just seven). The Reds have already conceded six this season (at the halfway point), so at a rate of almost twice as many, and rank way down in 11th. The Reds have gone from an incredible set-piece force into a mediocre, at best, set-piece force.

- So, Liverpool are, albeit on a smaller sample, only a fifth as effective from set-pieces without both van Dijk and Matip, and while better than that when Matip starts, still less effective compared to last season. As I’ve been arguing for six years, you can see small players sometimes win headers, but tall players are, on average, far more effective in the air (and the improvement in aerial duels correlates perfectly with every inch taller they stand in terms of average height); and while you can improve marking at corners, etc., a lack of height is hard to overcome.

- Of the measly four set-piece goals scored in the league since van Dijk’s injury, one was headed in by Matip, while he aerially assisted another. Nat Phillips and Rhys Williams won a good number of defensive headers in their games, but that’s not the same as attacking the ball in the opposition box. As brilliant as van Dijk has been as a defender, it’s his passing, his goals and his aerial threat in the opposition box that arguably turned Liverpool from a top four team into the 4th-best team ever seen in the history of European football based on the Club Elo rankings.

- Liverpool also conceded a set-piece goal to West Brom, after Matip had gone off injured. The Reds did well to limit Man United to just three corners in the recent game at Anfield.

- As a result of fielding teams that are about as short, on average, as any I’ve seen, Liverpool also no longer look as intimidating to play against. The only two tallish midfielders have been played in defence, where they are merely average in height. A Liverpool XI containing Alisson, Virgil van Dijk, Joel Matip, Fabinho and Henderson – plus the smaller mad-eyes Milner – suggests, in the tunnel that Liverpool will be no soft touch, and will aerially dominate and get stuck in. At the very least they will match the big bastard teams in the air; remember when Troy Deeney said van Dijk was just too good but also too strong and too quick? There was height, and heft. But a team of Thiago and Shaqiri in midfield, with three smaller strikers, suddenly looks like Liverpool – while not a soft touch – are not as physically imposing. Of the league games Liverpool have lost in the last couple of years, Henderson played in just one. Players like van Dijk, Matip and Henderson are intimidating, in a way that scrawny kids still learning the game are not.

- Liverpool’s air of invincibility has evaporated, with the intimidation factor. That harms Liverpool, while simultaneously helping opponents, in a “double swing”. But it can be rediscovered; Man City lost theirs for almost 18 months, but it seems to be back lately. They looked a soft touch for 18 months, now they’re physically stronger and yet still able to play good football.

PASSING AND CREATIVITY

- Last season, Virgil van Dijk was involved in almost 50% of Liverpool’s goals, in terms of having some kind of touch – often a meaningful longer pass to stretch the play – in the build-up (and sometimes he’d have three or four touches as the Reds moved the ball from side to side to wait for the right moment to pounce). By contrast, Fabinho as a centre-back is closer to 33% involvement. And Fabinho is a technically good midfielder.

- We’ll be looking in more depth at van Dijk’s passing soon. But not only do the Dutchman’s long passes make the pitch much bigger – both full-backs can push on more and know it will arrive, while the wide strikers can get in behind the opposition – but it also gives Liverpool another elite long-passer in the team. The only time the Reds had him, Thiago and Trent Alexander-Arnold in the same team was in the one-sided game at Everton that somehow ended 2-2 (mostly thanks to the officials).

- The lack of goals (and indeed, creativity) from midfield wasn’t an issue last season or the season before, as Liverpool averaged 98 points in 24 months and won the Champions League. The midfield held the team together and didn’t need to do the cutting-edge stuff. But obviously if the front three stop scoring as regularly, and the full-backs aren’t as effective – the five most attacking players in the Reds’ system – these issues from midfield becomes more important. The Reds’ two best midfield goalscorers, however, have had injury-riven campaigns. Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain missed four months, and isn’t yet sharp (or even close), while Naby Keita’s injury problems seem to be getting worse, not better – but we can only hope he finally overcomes them, as other players have (but of course, he could also go the way of those who can never stay fit long enough, and whose career peters out).

- Liverpool added midfield creativity in Thiago, but he hasn’t been match-fit, and while his passing has often been sensational, his tackling and pressing, which is based more on physicality, is not yet up to speed (but he had impressive defensive numbers last season, so he can do these things). The team was already struggling against West Brom when Thiago wasn’t even involved, and then he only played the final 18 minutes at Newcastle, so the rut was in place before he had even started a game at Anfield since his move.

- Andrew Beasley has drafted a piece for TTT on the problems with the Reds’ crossing lately, and that’ll be on the site this week. My general take has been that, lacking confidence, the full-backs stopped whipping in the technically-difficult-but-deadly crosses and went for safer “standing it up” crosses. But you need real pace and whip to allow smaller players to nip in and score; if the ball is high in the air and all floaty, it favours taller defenders and goalkeepers.

FINISHING

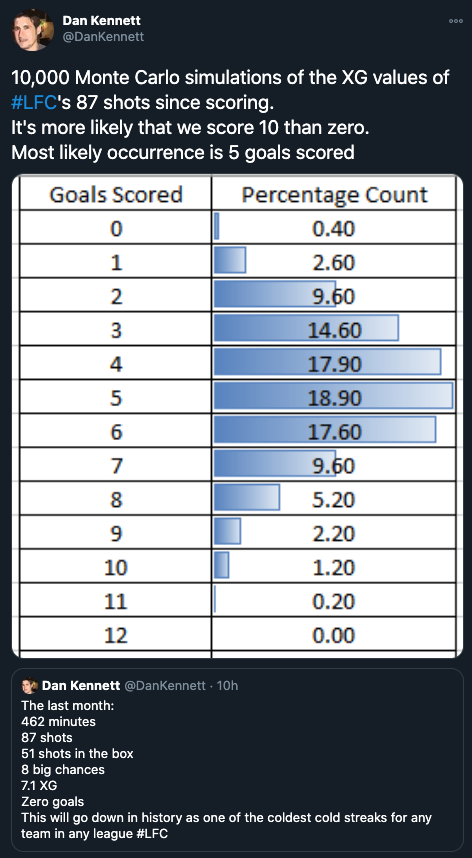

- I saw a stat that Liverpool’s odds of having over 80 shots and not scoring from the same chances, at the very point when the team were the league’s top scorers and had a world-class front three, was about 2,500-1. That may have been from Dan Kennett, but the image below definitely is.

- Confidence had evaporated, and to me it started with the only unacceptable display, which was against West Brom, where it all looked too easy, with the Reds having just scored their 8th goal in 100 minutes of league football. Suddenly, with no second goal and the Baggies offering a bit of fight after half-time, it wasn’t so easy, and conceding a sloppy goal to such a poor team heaped pressure on the Reds at the other end. That then led to poor decisions being taken, which can also perhaps be put down to tired minds under pressure.

- For a long time now, Mo Salah has been cutting inside too much, to the point where it has gone beyond predictable, and with rapidly decreasing success. He’s totally ignoring the space he’s shown to his right, and cutting inside and crashing into both a defender and a covering player; sometimes both. He’s trying to curl shots when there’s no space.

- Now, ignoring this space on the outside is fine if Trent Alexander-Arnold is busting a gut to overlap, to provide either a decoy or a genuine passing option if the path inside is blocked, but the full-back doesn’t appear to be fit enough right now to do that. Salah has to be brave and take one in every four chances onto his right, even if he fluffs them, because it will put doubt in the opposition’s mind and then open things up a bit more on his left when the defender hesitates. He has scored goals by cutting onto his right foot, but he’s just not even trying anymore – it’s likely a confidence issue, but could also be that if he goes onto his right he might have to end up crossing, which could be good for the team but not for him to win the Golden Boot. (Ergo: screw the Golden Boot.) That said, at Old Trafford yesterday, Salah scored with his right – a lovely deft finish – and had another shot with his right, while Alexander-Arnold bombed forward to offer the overlap. Both were huge signs of progress.

- Salah isn’t really an elite finisher in terms of chance conversion (apart from his penalties, rare as they often are), but he used to use his pace and clever play to end up with a ton of chances, and he’d take a high enough percentage to win games, and indeed, win the Champions League and Premier League. But now he’s looking a tad slower, maybe due to the lack of preseason, but also just a lot more predictable. He may be getting doubled-up on more, but equally, he is not helping by running into traffic all the time. (Again, this improved yesterday, but it’s just one game.)

- What I particularly like about Jota is that he doesn’t seem anywhere near as predictable as Salah, and is a more interesting dribbler. Jota appears more eager to jink left and right, with a more balanced style. He’s also proven more prolific than Salah was up to the same age (he got into double figures as a teenager in the Portuguese top flight), and like Salah, seemed to go up not one but two levels upon joining Liverpool. Jota hasn’t reached Salah’s best yet, but Salah hasn’t either. Salah’s all-round game in terms of pressing and closing off passing lanes may be more in synch with his teammates, but Jota is a pressing monster in terms of pure numbers. Salah turns 29 this summer, and while he has been an insanely good signing, it could be the high-value time to sell. (Or, at the very least, get him to use his right foot. Which, of course, he did to great effect yesterday.)

- Jota is one of Liverpool’s quickest players. As is van Dijk. As is Gomez. While you want skill, you also need a bit of height, a bit of muscle, and a heavy sprinkling of pace. Liverpool had so few weaknesses last season as they had height, strength, pace, passing range, energy and elite players at both ends of the pitch. This season it hasn’t been the same. Many of the qualities that only certain players can bring are absent with those players.

- Liverpool’s most ruthless finisher this season remains Diogo Jota. He’s played only 501 minutes in the league, or just over five games’ worth of time.

- A quick word on Jota’s injury. With the lack of preseason, and the games being closer together and with less time to do any intense training, Jota was selected to play at Midtjylland, just as if he was selected to play in a preseason game. Think of it like that. He needed the minutes – in that he hadn’t played a lot overall – and any time a new player can spend on the pitch is a bonus to that player, and his teammates, in terms of shared understanding (see “Perched“ for the importance of this, as well as the importance of very intense training to Klopp’s teams; it’s one of the key factors that improves so many players so dramatically as soon as they join his teams, dating back 15 years). It was a gamble that failed, of course, but not a thoughtless gamble. The odds of losing the only two new signings who didn’t already have serious knee injuries to serious knee injuries in the same fixture seems pretty Black Swan, along with losing two of the players voted into various World Best XIs to serious knee injuries in the same game at Everton. (That said, there was talk to which I initially didn’t give credence, that Jota was played in Denmark for the £2.5m bonus the club would get if it won the game; which still seems highly unlikely. The cash shortfall this season is stark, but if it was that important for that game, more senior players would surely have played. That said, as a guess, it possibly could have played a small role.)

- While Liverpool had too many blocked shots against Burnley, the shot from 18-22 yards has to be taken now and again against such teams, even if they aren’t “big value” chances. But they can lead to deflected goals (Salah’s against Spurs was the Reds’ only one so far this season, after just one last season), and they can break up the defending team’s mindset that Liverpool will only look to pass. Equally, you don’t want to resort to just taking potshots, or take shots when someone is in a better position. A good team will pass wide to cross, will shoot from 20 yards when there’s half a chance, and will slip in the clever through-balls in tight areas; mixing it up is often the key. The season before last, Shaqiri scored two deflected goals against the low-block of Mourinho’s United, and United this season are scoring deflected goals and also from 20-25 yards. As with everything else, a balance is required to not become predictable. And my biggest fear about Salah, unlike Mané and Jota, is that he is getting too predictable; while Firmino, while unpredictable, is having a terrible time in front of goal.

- Again, Firmino not scoring is not a problem if his movement, link-up and clever passes create chances for others to score; but if they are not scoring, then the goals have to come from somewhere. He had one of his best-ever finishing games against Palace, soon after a thumping header against Spurs. You could see what 2,000 fans in the Kop meant to him when he got that winner, and after the highs of the last two seasons, it all feels a bit flat and deflated right now: like a band who has just played Wembley Stadium now performing in an empty pub. You can be as professional as you want, but having reached all your targets, there can be a big comedown for a while. Football right now might feel more fun for teams coming off the back of bad seasons, and other teams may do better without a crowd, as to them it feels like less pressure. (The good news is that Firmino was superb in the second half at Old Trafford, and was at least assisting again. If Salah uses his right foot more, that will help, too.)

OFFICIATING

- I don’t want to keep focusing on this, but it’s been such a difference in many games of fine margins. I can’t even remember a season half as bad as this for bizarre decisions. I’ve seen many neutrals agree with how bad these decisions have been in isolation, but few are paying enough attention to add them all up.

- Liverpool have conceded more penalties than they’ve received. For a team that has scored almost twice as many goals as they have conceded, and who spend twice as much time in the opposition box, this is very weird – albeit we know Liverpool and penalties are weird. There are at least six clear-cut penalties Liverpool have been denied this season, and at least one utterly blatant red card for an opposition keeper (early in the game) ignored.

- Of the crazy SEVEN penalties Liverpool have conceded by the halfway point (on course for a bonkers 14), some were stonewall; but Joe Gomez’s handball at Man City was with his hand moving towards his side as he tried to get it out the way from a cross (contrasting with Southampton’s defender blocking Gini Wijnaldum’s goal-bound shot by making himself bigger with an outstretched hand); Fabinho’s against Sheffield United looked a clear foul outside the box that actually wasn’t a foul upon the replay, but surreally turned into a penalty; and no one on the pitch saw the slightest touch by Andy Robertson on Danny Welbeck that failed the “clear and obvious” error bar by needing countless slow-mo replays, the kind that has not been used to show clear penalties for Liverpool, such as the scything down of Mo Salah at Aston Villa when the game was just 1-0 (or the late tackle on Sadio Mané after he shot against Burnley at 0-0). Neco Williams’ foul in the Brighton game was a stonewaller, as was Alisson’s foul on Ashley Barnes, although Barnes was looking for it – but it was still a foul, just as Connolly was looking for Williams to foul him (and Williams duly did). Thiago’s foul on Timo Werner was very hard to discern on the replays, and Werner flew forward at some pace, but it was one of those that if there was a slight touch it could easily send a player tumbling – although this logic is not applied to Mo Salah and Sadio Mané.

- Most of the super-tight offside calls in the Premier League this season used to disallow goals – the ones the technology is too limited to properly discern – have involved Liverpool, and counted against them. I won’t focus too much on the decisions, as I’ve covered them time and again and the list, and the detail it requires, is too long. But as a Liverpool fan, whilst at times driven mad by officials, I’ve never seen anything even half as weird as this season.

- Sports scientist, coach and Liverpool fan Simon Brundish has Liverpool at a net balance of -16 on “subjective calls”. Now, these are subjective, obviously. But in calls that could have gone either way, that’s a staggering tally – and yet not surprising to anyone who has watched every Liverpool game and paid some attention.

TOO MANY NEW PLAYERS?

- Do Liverpool have too many new players? Last season Liverpool won the league with the same team that had won the Champions League, with the understanding built over years. Obviously that reaches a peak, when you have to start to refresh. This season, as well as direly needed left-back cover, two great additions were made, in theory, but Diogo Jota got injured, as did Thiago; but the latter is now playing and learning about his team-mates and the Premier League as he goes, whilst not being fully match-fit. Kostas Tsimikas joined, then joined the buggered-knee brigade.

- By contrast, Manchester United have stopped adding showcase signings and churning up the squad, and are top of the league with more-or-less the team they used last season. Donny van de Beek has barely started, and Cavani seems to start only half the matches. A stark example of how adding “great signings” is Chelsea: a ton of mega-money signings this season (and a couple of cheaper ones), and absolutely no understanding; often with six new players in the team, they have, to me, a title-winning squad on paper, but as yet, no shared wavelength, and an unproven manager. (Of course, since I drafted this article they’ve sacked Frank Lampard.) You can’t skip the team-development phase just by buying everyone who is highly sought-after.

- Another problem is that Liverpool’s “new” players used were actually often youngsters, who were part of the team dropping points at Brighton, at home to West Brom, and then at Newcastle, by which time a rut had set in. They have some understanding from training with the team for a couple of years, but they have all made costly mistakes, as tends to happen more frequently with those learning on the job; and they do not yet have the hardened winning mentality nor the canny nous to play to the level of the players they have deputised for. And that is perfectly normal.

- This was never intended to be a transitional season, but it has almost become one by default, with so many changes to the lineups. When you lose 5-6 of your best players to injury, then it has a knock-on effect. You move 5-6 of your squad players, who can never be even remotely as good as the likes of van Dijk and Thiago (who are elite world-class players), and so your team will not be as good. But then, these really good squad players are in the XI, and so the bench is suddenly full of everyone who isn’t normally in the matchday 18. Maybe some are even needed in the XI. So you have less quality to turn to. Liverpool have a great squad, but take 6-12 players out of the equation and you will have massive gaps. No squad can cover those kinds of losses over a longer period of time (but they may do in the short term).

CONCLUSION

There are no easy solutions to get back on track, although the performance at Old Trafford was a big step in the right direction, in an unlucky narrow defeat. In some ways, to lose 3-2 was better than losing 1-0, with scoring goals being the main issue lately – and Liverpool having done enough to beat teams like Burnley without taking their chances. Finishing is often so random, and I recently noted that in the middle of last season Liverpool had a run where every team the Reds played missed easy chances, and anything on target Alisson saved. Liverpool probably didn’t deserve to win some of those games, but they won them; they didn’t deserve to lose or draw some of the recent games, but they did. It happens.

Klopp will get everyone working even harder, but without the preseason in their legs, with so many rusty after injury, and with the pressure setting in ever since throwing away the lead against West Brom, it won’t be easy. Liverpool could easily remain a weak set-piece team, simply because they may lack their best set-piece players; as noted, Matip makes a difference, but van Dijk will not be back soon.

If Liverpool can get Jordan Henderson into the midfield with Thiago sometime soon, to provide Thiago with a bodyguard, then things can improve. Jota returning next month will be a big bonus. If (and obviously it’s a big ‘if’) Matip stays fit, that’s huge, in all senses. But of course, further injuries could only make matters worse.

More time in the team for the new players and the youngsters will help them to settle and grow, but if Liverpool have to rely on the youngsters then it will be tough.

Only now, at 20 and after three years of increasing minutes, is Phil Foden making a difference to Man City, rather than just making up the numbers. Trent Alexander-Arnold was half the player at 18 that he was at 21, even though we could see his qualities early on – but the consistency was not there (it has gone this season, but mainly due to injury and illness).

Curtis Jones will benefit hugely from this season, and has improved massively since last season, but in the recent run has been often a weaker link in the chain. I always cite the example of Jordan Henderson having a fairly torrid time on the right of midfield in Kenny Dalglish’s one full season second time around, but that gave Henderson vital experience, just as Jamie Carragher, who struggled as a teenage centre-back, developed at right-back and left-back before he looked the finished article and moved to the heart of the defence in 2004. Steven Gerrard scored just one goal in his first 50 games for Liverpool, before scoring almost 200 thereafter; but he needed those first 50 games to develop as a player, to fill out and grow, and to adjust to top-level football.

Ideally, Jones and the Williamses (which sounds like a bad 1970s sitcom) wouldn’t have been in the team very much this season as teenagers, but they have been. They will learn, and they will be better for it. But if they are unable to play much in the second half of the season – because many of the key senior players are back – that should be a good thing, too.