By Paul Tomkins.

One thing people always tell me is that Liverpool ‘won’t win the league with X manager’. Ten years ago I’d have gone along with this, as I still thought it football was all about having the right manager. But over the past decade it has been clear to me that Liverpool won’t win the league with any manager. I’ve written that before, but I’ve never had as much proof as I’ll lay out here. (And I’m always looking for better ways to explain it.)

The fact that Brendan Rodgers came close last season only raised the spectre of a 19th league title, and a 25-year wait. We got excited. But I believe that in this article I offer proof that Liverpool winning the title is far more difficult than when United ended their 26-year wait in 1993, or when Arsene Wenger ruled English football with his great Arsenal side. At the start of every season, no one should ever mention Liverpool winning the title as some kind of obvious possibility, just as no one mentions Nottingham Forest winning a third European Cup (although mainly because they never qualify for it anymore).

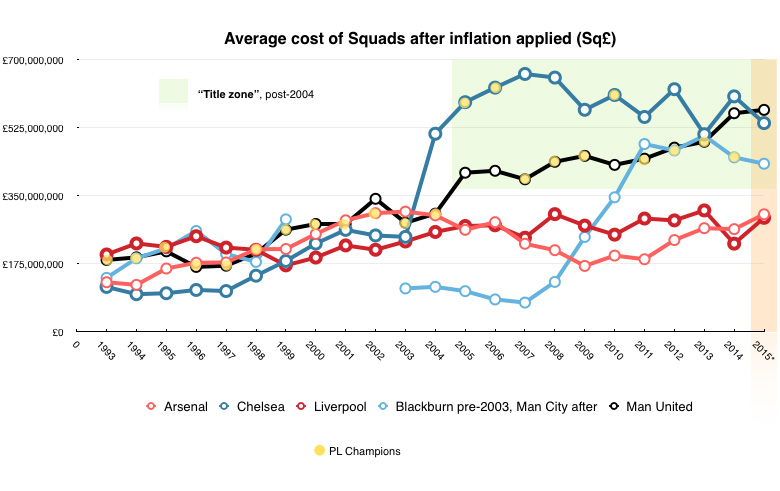

I touched upon this last week, but it’s worth making it crystal clear. Until FFP really bites, and until Liverpool have a bigger stadium, then the money the club spends on transfers will never be enough. You cannot blame FSG for living within the club’s means, and even then, they are dangerously close to the 70% mark in terms of wages-to-turnover. Years of neglect, and falling behind rich oligarchs, has left the Reds stranded. When the Premier League began, Liverpool were the richest club. By 2005 they weren’t even half as rich as the richest club (based on squad costs). Now they have the 5th-most expensive squad.

I find it hard to even discuss football with people who don’t know the kind of things contained within this article; the kind of things I’ve been discussing for years now. Do Spurs fans say “we’ll never win the league with this manager”? They could have Pep Guardiola and they still wouldn’t. Do Everton fans still think they stand a remote chance of what Howard Kendall gave them? They could have the ghost of Dixie Dean and they still wouldn’t. Do Aston Villa fans think it’s still 1981?

Liverpool won lots of titles when football was the way it was; and then football changed. As they say, timing is everything.

Now, last season I said there was no way Liverpool could win the league, even when they led the table at halfway, and yet they nearly did. But ultimately the reason I said they wouldn’t was probably behind the failure; i.e. City had a massive squad with great depth, and Liverpool had a smaller squad, with cheaper players, and couldn’t replace key men. Once Jordan Henderson was suspended there was no one close to his level (as it was then) to put in. It could have been Suarez or Sturridge who got injured or suspended in the run-in, and the lack of depth would have been exposed. (Oh, and City had the experience of having been there and done it.) You can talk about bad defending and slips by players, but great attacking got Liverpool into a position that was above expectations.

The fact is, since Roman Abramovich arrived in England – and allowing for one season of investment before it really kicked into gear – only three clubs have stood a chance of winning the title, based on our TPI model. Those three clubs are Chelsea, Manchester United and Manchester City. Indeed, between 2005 and 2010 there were only two clubs with the wherewithal, and those were Chelsea and United. City became ‘possibilities’ in 2011 according to our TPI model, and guess which three clubs have won all of the titles in the past 10 seasons?

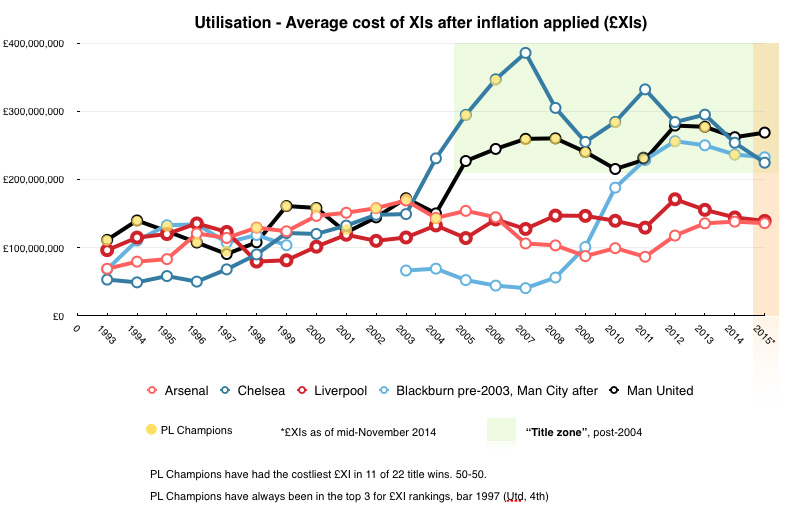

For the purposes of this piece I’ve updated the graph from last week, and added another, to make it apparent how teams win the league. And it’s crystal clear that Liverpool and Arsenal are mere also-rans. At first glance the graphs may seem complicated, but take a moment to let the information sink in. I’ll go on to explain what it all means.

The yellow dots represent the title winners. If you look at Manchester United in 1993, you can see that they had the most expensive £XI (the £XI is the 38-game average cost of the starting line ups, after inflation is applied. All teams are shown in 2014 money.) At this time, teams contained more ‘free’ homegrown players – so even when converted to 2014 money the teams were cheaper – but even though United had the costlier £XI, Liverpool’s squad was more expensive; indeed, the most expensive in the land at the time. (Thanks, Graeme: both Riley for creating TPI with me, and Souness, in irony, for such bad spending.)

The costliest squad will provide the title-winners roughly one-third of the time. The costliest £XI will provide the title-winners half the time. In 1993, compared with Liverpool, United had more of its expenditure in the team, less on the bench (or injured). We call the £XI the “Utilisation”: how much of the spending ended up on the pitch.

However, for the first eleven Premier League seasons the differences in squad and £XI costs were fairly minimal; it was an era when there was no clear financial heavyweight miles ahead of the rest.

When Blackburn – the Man City of that era – won the title in 1995 they also had the costliest £XI, but like United, not the costliest squad. Even so, the cost issues were less marked than they are now; theoretically the richest four clubs, along with Newcastle (who aren’t on the graph) could claim to have a fighting chance. It’s a neat cluster, with teams interchanging ranking positions all the time.

When Arsene Wenger won his first title in 1998, Arsenal also had the costliest £XI. But it was close. Back then, everything was close.

The Title Zone

If you look at the two graphs, there is something I’ll call the Title Zone, shaded in green. Since Arsenal won the title in 2004, no one outside of this zone – either in terms of squad cost or the average paid for the XIs – has won the title. Liverpool got vaguely close to entering the zone in 2012, but at no point before or after were they even close. Even in 2012 they were still a staggering £80m adrift in terms of the average cost of the XI after inflation is applied (£XI). In other words, they were still a third of the money short.

You can see Manchester City building up from 2007 onwards, with real acceleration from 2008, and they only won their first title after two years in the Title Zone. Their squad got a fraction cheaper in that second year, but their £XI actually rose by a decent amount. For whatever reason, they were getting more of their expensive purchases on the pitch.

If you do not have an £XI in the Title Zone, or a squad cost (again, after inflation is applied) in the Title Zone, you won’t win the title. That may sound simple, but that’s how it works. Or at least, how it’s worked for the past 10 seasons, and how it appears to be working again this season.

If you take nothing else away from this piece, then please consider the next two paragraphs.

– No team with an £XI lower than £210m has won the Premier League in over a decade. Liverpool’s current £XI is £138.9m, over £70m short of the minimum. (And indeed, it was £95m short of City’s last season.)

– No team with a squad that cost less than £397m (after inflation) has won the title in over a decade. Liverpool’s current squad cost (Sq£) is £293m, over £100m short of that minimum. (And indeed, was a whopping £140m short of City’s last season.)

Any time I analyse football I do so with these kinds of figures in mind. It doesn’t tell me that Liverpool must give up; it tells me that unless Liverpool can be extraordinarily clever, as well as lucky, then in any given season they are unlikely to beat all three of the clubs in the Title Zone. Think of it like breaking into a high-security bank: you may get past the first security system, if it’s faulty, but your chances of making it past all three diminish with each new challenge.

As Liverpool are working within their budget (as a percentage of turnover), it’s hard to say that spending more is easily done. City, Chelsea and United stocked up on great players for big fees before FFP bit. In fairness, Liverpool tried a version of this – Big Spending Lite – in 2011, but it was lower in scale, and made with an awareness of FFP looming. For all the naivety of David Moores, and the rank dumbness of Gillett and Hicks, the Reds probably never stood a chance of competing anyway. Liverpool missed the boat by not ‘monetising’ at the start of the Premier League (when United pulled away), and then they missed the next boat – or rather, yacht – when it came to billionaire benefactors.

Given that roughly half of all transfers end up not really making an impact – as shown by our TPI work – you can say that the Reds’ four big-money signings of 2011 were, as you’d expect with the law of averages, a 50/50 hit/miss ratio. Carroll was a flop; Suarez a success. Downing was a flop; Henderson a success. Carroll and Downing had gone by the time Suarez and Henderson helped Liverpool in a title challenge. As I noted last week, in terms of instant success, perhaps only one in four big-money signing has an excellent first season, and it works here too. Suarez was extremely good at first, then sublime. Henderson was hesitant at first, and then, last season, a key player.

Equally, Liverpool only got back approximately a third of what they paid for Carroll and Downing. Richer clubs can more easily write off such losses. Under Graeme Souness, Liverpool paid big money (£20-30m fees, TPI), but got precious little back from those investments. Equally, Gérard Houllier bought some good defensive players, but the club recouped very little from sales of those he bought. People sneer at ‘resale value’, but if you buy a house you want to be able to sell it years later; if you lose it for nothing, you can’t afford a new house.

Both Chelsea and City discarded expensive players at quite shocking levels on their way to the top, although in fairness to Chelsea, their buying in the past couple of years has been outstanding. Their wealth has helped them focus on the here-and-now, but also tie-up a load of promising youngsters.

Whenever anyone says Arsene Wenger is now out of touch, and way below his old standards, look back on the graph to his three titles (in reverse order, 2004, 2002 and 1998). Wenger hasn’t necessarily got worse; quite simply, the landscape was set to change, and even began to do so during his last really successful season.

Look at the upward projections in blue before Chelsea’s success, and United, in black, responding to the big spending. Then look at the similar sharp rise at the lighter blue of City in the second half of the last decade; getting ready to attack, like a shark rising to the surface. Indeed, City never quite hit the “expense” heights that Chelsea managed, but their investment was over a shorter period of time (bar that one massive upward swing in squad cost in Abramovich’s first season).

All the data shows that Arsenal and Liverpool are miles adrift from the ‘big three’. Not only is there a chasm between the average cost of the XIs each season (including 2014/15), there’s a chasm between the squad costs, too. None of this is to say that Arsenal should be 8th and Liverpool 12th, of course. That is not good enough. But equally, Liverpool did miraculously well last season, and Arsenal, to date, have managed to hold onto a place in the top four every year, which, according to the model, is about all they can ever hope for. Maybe Wenger could have spent more, and is therefore in some way culpable, but to me the haven’t realistically stood a chance of the title since 2004. They are at least investing in the XI, now that their stadium is reaping greater rewards from ticket revenue, but the gap to close remains large.

Arsenal’s squad costs have risen, to overtake Liverpool’s for the first time since 2006. The exact same rise is true of their £XIs, although they are still just behind Liverpool in that regard (if Ozil was fit he’d tip them ahead, but even having two c£40m players would not push them into the Title Zone).

The evidence in this article shows that the bigger the squad you have, the more you can “put on the pitch”. It is happening in Spain with Barcelona and Real Madrid, whose squads get bigger, and in Germany Jurgen Klopp’s Dortmund have been scavenged by Bayern Munich.

The Premier League ‘rich three’ are so tightly grouped that the title will come from one of them; but it ultimately comes down to whose manager gets the most out of their talented collections, and who has to overcome less bad luck. Is one team bogged down in Europe? Is one team defending the title, which comes with different challenges? Are key players missing? But when it comes to mere standard injury issues they usually have the strength in depth, as shown by the squad cost.

You can beat the odds if one of the big three has a bad season; United stumbled badly in 2013/14. But what are the odds on United, Chelsea and City all having bad seasons at the same time? – and with Arsenal, the other possible challenger, also failing to match Liverpool (when it almost looks a 50-50 coin toss as to who will finish higher, based on wherewithal)? Chelsea had a ‘bad’ season last year and yet finished with 25 wins and 82 points. Prior to the advent of the Title Zone, 82 points would win you the league half the time. The über-squads with world-class managers have raised the bar.

I stated time and again last season that we were seeing a freakish over-performance from Rodgers’ men. When I said that the Reds would not win the title I noted that it would be one of the great achievements if they did. They failed, narrowly, but rather than thinking we need to build on it, push on again, keep up the momentum, etc, the reality was that a fall was fairly inevitable. Teams don’t really buck those odds twice in a row. Again, look how far adrift the Reds were in 2009 in terms of wherewithal, and how close they came. Look at the similar ‘decline’ a season later. It’s almost as if everything goes into one extraordinary push, then collapses in exhaustion.

My feeling is that whatever Liverpool did this summer, they’d still be seen as in some kind of decline. An injury to Sturridge made life harder after the sale of Suarez, and the signings aged between 24-32 haven’t settled immediately into the team. (The investments in a handful of reasonably-priced high-potential 19-22 year-olds makes perfect sense to me.)

Rodgers’ tactics have been called into question, and there are probably some very valid criticisms of his methods (although some of the criticisms I made last season were overridden by an 11-game winning streak). The team is playing very poorly. Right now, Rodgers is not getting the most out of the players at his disposal, and therefore questions need to be asked. (Some of which I cover here.)

But even though it’s easier said than done right now, just two wins would put Liverpool back to the weight they should be punching. The problem is that two more defeats could put them into the relegation zone.

See www.paultomkins.com for my non-football writing.