By Paul Tomkins.

The lack of sophistication and in-depth thought in most transfer assessments drives me to distraction. As I’ve noted before, I’m not a student of the tactics of the game, and I don’t write match reports or do transfer gossip. What I have done for the past half a decade (and for a few years beforehand, with less knowledge) is look, in detail, at how transfers work, and how transfer spending correlates with success.

It’s a burning issue with Liverpool right now, with talk of “£120m wasted”. Now, it’s hard to cover every aspect of what is a big, nuanced argument, which I have spread across many articles, and indeed, our 2010 book, Pay As You Play. As ever with this work, once I start delving I find several new pathways to explore, and have to draw a line; leaving those for another day.

Wherewithal

Many fans talk as if Liverpool, this summer, were at the same stage as Chelsea, Arsenal, Manchester City and Manchester United. One season’s title-challenge did not alter the fact that the Reds had spent the last five seasons out of the elite (whilst those four teams were in it), losing money as a result, and that the squads were in any way comparable. Three of those four teams have squads that cost almost twice as much as Liverpool’s; and while Arsenal’s squad cost is closer to that of the Reds, their wage bill – financed by consistent Champions League participation and a bigger stadium with higher ticket prices – has grown at a far greater rate.

Liverpool earned their 2nd place last season, but it was achieved with a handful of excellent players (and some padding), and no extra games. It wasn’t sustainable, especially once the two best players last season – Suarez and Sturridge – were both absent.

Here are some facts.

Last season, Liverpool had a squad that was lacking depth. (I think we can all agree on that.)

In the summer, Liverpool needed to add quality as well as quantity.

Liverpool were in a very difficult situation with Luis Suarez, who a) desperately wanted to join Barcelona, and b) was facing a two-year ban the next time he bit someone.

Liverpool could have signed players with poor injury records. If they stayed fit, hindsight would say the gamble was worth it; if they didn’t, people would say it was madness.

Liverpool qualified for the Champions League, but after a five-year break, were not an established Champions League force anymore.

Now, maybe Liverpool could have kept Suarez, even if he was guaranteed to miss the first few months of the season. But if anyone thinks doing so was simple, they are deluded. Suarez moved up the ladder by leaving Ajax for Liverpool, and now he wanted to do the same with a move to Barcelona.

Now, maybe Liverpool could have signed Loic Remy or Radamel Falcao. But Falcao would have involved a big one-season loan fee and massive wages, for a player whose knee issues have limited his playing time. And the signing of Remy – who is hardly a world star – would have meant ignoring the medical he failed; and if you do that, why have a medical in the first place? Without knowing the ins and outs of that medical, I can only presume that he has a latent problem that could flare up at any moment; that it hasn’t happened yet wouldn’t stop people from calling Liverpool stupid for paying £10m for a player who, in his first or second training session, ended up crocked. (With hindsight, everyone would have said ‘what a dumb move!’ See Aquilani, Alberto.)

So, Liverpool needed quality and quantity. But now people seem to be arguing that quality was the vital factor. Well, maybe. But if Liverpool had eight or nine injuries at this stage, the subject of quantity would be broached. Then it would be “we needed a much bigger squad”.

However, to bring in both quality and quantity costs an absolute fortune. If you’re going to increase the squad size by a net amount of five or six, then that’s a big hike to the wage bill.

The ignorant do not bring bliss

There are different levels of transfer knowledge. The gross spend argument is ‘entry level’ – your basic rookie mistake – and almost always misleading. Spend £50m on players but sell your entire remaining squad for £200m, and you haven’t just “spent £50m”.

Net spend is better, clearly. That’s level II. But it falls down depending on when you choose your start and end dates. A team can have a £0 net spend this summer having spent £500m last summer; it still has those £500m players, plus the ones it already had. Unlike gross spend, net spend takes into account the loss of a massive asset like Luis Suarez.

For me, the key is to look at how expensive squads are (with transfer fees adjusted for inflation) and to consider wage bills. It’s still not perfect, but it shows a club’s wherewithal. That’s the vital word here. Wherewithal. The ability to have quality and quantity; strength, and strength in depth.

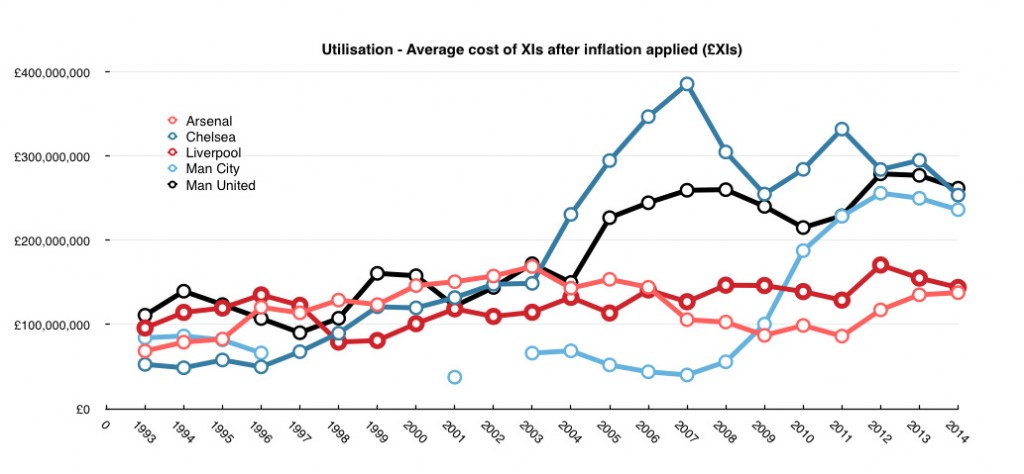

What follows is what I feel is a fairly definitive graph on wherewithal. It is the average cost of the five biggest clubs’ XIs for each season, with inflation applied. What it clearly shows is that things went ballistic in 2003, as Chelsea started to spike; changing, even with inflation applied, the kind of money spent on a team. United followed suit, albeit never quite matching Abramovich’s XIs. And City can be seen joining the party in 2009. The net result of all this was that by the end of the 2013/14 season, there was a tightly-gathered cluster of three clubs with XIs that cost around £250m (TPI) per game.

What’s fascinating is the trajectory of the other two clubs, Liverpool and Arsenal. If you look at the first eleven seasons, then you have four of the five clubs jostling for position, tightly packed and overtaking each other (with City not even in the Premier League). Once you get to 2004 you see that two of the clubs have invested massively in personnel, and suddenly Arsenal, who won the title three times in the previous six years, are left behind. Ditto Liverpool.

So, looking at the graph, at the point where Arsenal and Liverpool fall away – or rather, stay steady as the others leave them for dead – who would you say would win the next seven league titles? If you think they went Chelsea, Chelsea, Man Utd, Man Utd, Man Utd, Chelsea, Man Utd, you’d be correct. However, look at 2012: there are now three teams grouped together. This would tell you that the newcomers, Manchester City, are on a par with the other two, and therefore likely title candidates.

Look at Arsenal and Liverpool’s trajectories and you can see clubs that won’t win the title. By rights they shouldn’t even be getting close. And yet in 2009 and 2014, Liverpool went close. Look at the gap in wherewithal with the clubs above them on the graph. The failure was not in missing out on the title; simply getting close was a miracle. There is a league of three, then a second tier of two, and then the rest of the Premier League.

Remember, these are not squad costs, but the talent that made it onto the pitch. Of course, expensive reserves mean that the £XI can remain high.

I’ll update the graph for this season once I have all the data from Graeme Riley, my partner in creating the Transfer Price Index. My guess would be that Liverpool’s XI isn’t much closer to those of the big three, because despite fielding a £20m centre-back and, occasionally, a £23m midfielder (Lallana), Liverpool lost a £29m striker (Luis Suarez’s £23m in 2014 money), and Balotelli, at £16m, is roughly the same as what Daniel Sturridge cost post-inflation. Lazar Markovic, at £20m, has barely featured in the league. And of course, Lovren is replacing Sakho, who cost almost as much. If there’s one thing we can take from the figures it’s that not enough of the Reds’ summer investment has made it into the XI, but more on that in a moment.

Arsenal, meanwhile, have added the £35m Sanchez, but lost the services of the £42m Ozil.

Just buy world-class players, dammit

So, if you buy expensive players you should get instant rewards, right? What’s interesting is that although the successful clubs have the most expensive squads, they also sign plenty of costly duds; as I’ve been saying for years, it’s this ability to take big losses on high-price failures and not break their stride that increases their odds of winning things.

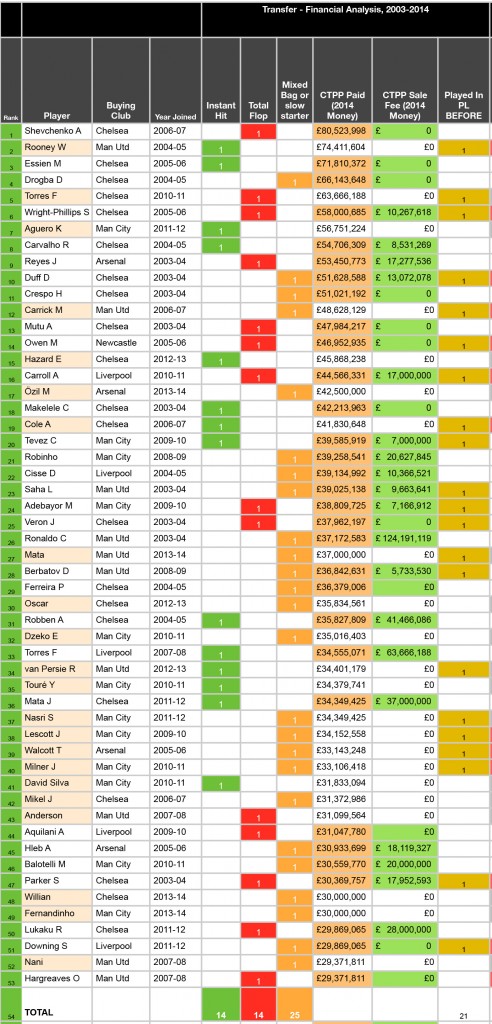

In terms of individual purchases, I thought I’d look at the 50 most expensive ‘big club*’ signings between 2003 (when Roman Abramovich started driving up prices) and 2014 (with this summer’s signings excluded). In the end, 53 Premier League players fit onto my screen in the spreadsheet, so I went with the top 53. How did these 53 players do after their big money moves? To be specific, I’m interested in how many set the world alight in their debut season.

(*Chelsea, Liverpool, Man United, Man City, Arsenal, Spurs and, perhaps generously, Newcastle United, on account of their Champions League participation in the qualifying timeframe, and their ability to make at least one major marquee signing who ranks above £40m in 2014 money.)

Now, these are the top 53 in terms of TPI-inflation adjusted fees. Everyone who qualified cost between £29m and £80m in “2014 money” (as calculated by our football inflation model) between 2003 and 2014. The most expensive player remains Andriy Shevchenko, who cost £30m at a time when fees were, on average, around two and a half times lower than they are now – so now that fee equates to £80m. In other words, he cost £30m when £30m was a heck of a lot more money than it is now.

For the purposes of this quick assessment I wasn’t rating the quality of the footballer but the success of his transfer. Indeed, in this instance I assessed whether the signing made a huge impact in their first season; or if they were hit-and-miss (which also includes eventual stars who were slow starters); or if they were a waste of money. Some, like Alberto Aquilini and Owen Hargreaves, were fine footballers whose injuries curtailed any possible progress. You may disagree with a few of my subsequent conclusions, but on the whole I think most are undeniable.

Now, when it comes to the less undeniable conclusions, there are complicated cases like, for example, Didier Drogba, who was a useful target-man in his first season with Chelsea, but had a fairly mediocre goals return. Overall, across a decade at Stamford Bridge, Drogba was a big hit; but he received a fair amount of criticism for his goals record until his third season in England, when he suddenly became twice as prolific. He was always a handful, but far from perfect.

Ditto Dimitar Berbatov at Man United, with just nine goals in his first league season (31 games). You’d have to rate his time at United as a bona fide success, as titles were won and he had prolific campaigns, but he didn’t make a great initial impact. Likewise, Cristiano Ronaldo ranks as the greatest buy of the Premier League era in my TPI Coefficient (which I designed to assess signings in terms of money spent, games played and profit/loss on a sale), but he was seen as a bit of a lightweight show-pony in his first season or two (at which time he was, let’s not forget, still very young). His fee in today’s money was £37m, so a teenager at that price in 2014 would be expected – rightly or wrongly – to deliver straightaway. (The fact that he was sold for £124m TPI nails him as the best signing of the era.)

Players like Oscar and Fernandinho had decent enough debut seasons, with really good games here and there, but weren’t consistently excellent, or even consistently in the team. I had them down as mixed-bags. (I’m obviously going on the general buzz around these players, as I can’t claim to have watched them all to equal degrees.) I was perhaps a little generous with Stewart Downing but was in the camp that believed he wasn’t as bad as many thought, even if he wasn’t great either.

What’s clear, however you slice it, is that there are a far greater number of players who failed to make a significant impact in their debut season than there are those who were hit-or-miss/slow starters, or just failures from start to finish.

I make it that a mere one-quarter (26%) hit the ground running and stayed running. Think of Torres at Liverpool, Aguero at City, Van Persie at United (even though he’s subsequently dipped, he was vital in winning United the title and still looks like a great signing).

A further 47% – almost half – could be considered as showing potential in their first season, without blowing anyone’s mind; even if some did go on to be true greats (Ronaldo, Drogba, et al). And a further quarter failed to get close to justifying the expensive price tag. (As a note, in total, 22 of the players were still at their clubs as of the end of last season, and so perceptions of their value for money can still change.)

So, by my calculations, 74% of the most expensive signings since 2003 failed to have a clear and sustained impact from day one. That’s three-quarters who didn’t set the world alight early on, beyond perhaps a good game or two.

Thirteen of these players were English or Irish, and 21 of the 53 had already played in the Premier League (or in Theo Walcott’s case, the Championship).

Out of the 14 players who were instant and spectacular hits, just five (36%) had played in England before; making nine (64%) who arrived in this country and adapted like ducks to water. Indeed, with 14 players also clearly flopping, it’s interesting that a greater proportion of the flops actually had prior Premier League experience; exactly half of the flops had already played here, but only 36% of the success were ‘used to our game’. This suggests either that big money signings from our own league are overpriced; or that, whether or not they are overpriced, they offer no clear benefit over fresh imports – and if anything, offer less.

None of this is to say that all overseas players therefore should not be allowed time to settle, as clearly some need it (Arsenal’s great team of 2002 featured Bergkamp, Henry and Pires, all of whom clearly struggled in the first four-six months, before becoming three of the best this country has ever seen). Every transfer has to be judged on its own merits, as every player is unique, but this is the picture of the general trends.

It’s also important to remember that few of these 53 were considered poor players when big money was paid for them. Perhaps Andy Carroll’s was the most surprising fee, but he looked a threat at Newcastle (Rio Ferdinand named him as a very tough opponent), while Shaun Wright-Phillips was an excellent Premier League player who just didn’t adapt to life at a club with a bigger squad and higher expectations, as well as the pressure of having a big price-tag. Like Wright-Phillips, Damien Duff was also a player I know many Liverpool fans coveted before he moved to Chelsea and gradually faded away, at which point, after a decent first season, everyone conveniently forgot about how they’d touted him for greatness.

World-class?

So when people talk about the need to sign ‘big-name’, ‘big-money’, ‘world-class’ players, I think they recall only the successful ones and ignore the many instances when it just doesn’t work (or takes time to work).

And anyway, ‘world-class’ is a subjective term. The buzz that surrounds Juan Mata might have you label him such, but in reality he is, at best, ‘international-class’. If we say that world-class players are those who regularly excel for their country on the big stage, or who are consistently one of the stars of the Champions League, then Mata is not at that level. He is a very good player, who has a reasonable 36 caps for an outstanding national team by the age of 26. (Compare with Cesc Fabregas’ 94 caps at the age of 27 and regular Champions League football for over a decade.)

I’d say that just 11 of the 53 signings were undoubtedly world-class at the point they were signed. That’s just 21% – or one in five – of the most expensive transfers of the past 11 years. That’s one world-class signing arriving into the Premier League per season.

Of course, the figure of 11 is my subjective assessment of how player were perceived at the moment of purchase. If you want to be generous, you could add Wayne Rooney, although at 18 he had ticked the ‘big international tournament’ box, but wasn’t a top scorer in the Premier League (he’d never reached double figures) or someone who had played in Europe (zero appearances). He clearly had huge potential, though.

Most of the other 42 players were ‘international class’, although a few – Andy Carroll, Joleon Lescott (when joining Man City) and Theo Walcott – had barely tasted international football and certainly hadn’t played in the Champions League. At least with Walcott you could argue that, as with Rooney, there was world-class potential. Others, like Yaya Toure – hitherto a mere squad player at Barcelona – only earned ‘world-class’ status after arriving in England.

The ‘world-class’ 11? – Shevchenko, Aguero, Crespo, Ozil, Cole (Ashley), Makelele, Van Persie, Robinho, Veron, Silva and, of course, Torres, who was still rated by many as the best true centre-forward in the world at the point he joined Chelsea for £50m (£64m TPI). Even then you could debate whether or not Robinho was ever as good as the hype, of if David Silva was considered world-class before he arrived in England – but he was close. Equally, Veron was arriving at Chelsea on the back of a mediocre time at Old Trafford, but he was still lauded as one of the world’s great midfielders.

Of the 11, only five – less than half, to the mathematically alert – proved resounding successes: Silva, Cole, Makelele, Van Persie and Aguero. Of the other six, Robinho had some bright moments, as did Ozil (for the first few weeks), and Crespo’s goalscoring record wasn’t too bad; but none of that trio were big hits. I can’t recall much about Veron’s time at Chelsea, which perhaps says a lot. And the worst value for money when it comes to strikers remain Torres and Shevchenko – £145m TPI between them, £0 recouped, with Torres due to leave on a free. Liverpool lost far less on Andy Carroll, lest we forget, after West Ham took him to London. I can still recall the terror I felt when Chelsea signed both Shevchenko and Torres, and yet neither did any better than the far more limited Carroll at Liverpool.

So in the last 11 years, it’s fair to say that, give or take a debatable inclusion/exclusion here or there, the 11 most expensive ‘world-class’ Premier League signings have seen a 55% flop rate and just a 45% hit rate.

This ties in with what Dan Kennett termed “Tomkins Law”, when, using the TPI Coeffficient, I ranked 3,000 Premier League deals based on fee paid, games played and profit/loss*, and concluded that only 40% could be labelled successful. These were all deals, not just the expensive ones.

(*All prices adjusted for inflation. Appearance data includes total league games, plus the percentage of games started. Sale fee also included a ‘mark-up’ factor.)

There are lots of different ways to rank signings, but I’ve used both the subjective (expensive players I would term ‘world-class’) and the objective (purely data-driven results on 3,000 deals), and it always tends to boil down to something like 40-60 or 50-50 splits.

If most squads are comprised of 25-40 players, and every team can include only 11 starters, then there will always be signings who are either not good enough to get a game, or who are unfortunate to be excluded (due to injuries, suspensions, or an exceptional player ahead of them). So at any given point in time, some perfectly fine footballers will be labelled flops because they’re not getting a game. If every club has at least a couple of home-grown players in its team, then that’s just nine spaces open to approximately 20-30 signings, and unless they all are rotated to perfection – to the point where they are all brilliant without playing each and every game – then there will be baggage and ‘dead wood’ in any squad.

So far this season, Liverpool cannot count on any clear successes from their nine signings, although one hasn’t even arrived in England.

Right now it looks as if the Reds bought poorly. It seems that an excess was spent on tricky little midfielders and left-sided centre-backs (once taking into account last summer’s spending), which suggests an imbalance. And although approximately half of the new signings were old enough to expect a possible immediate impact, none has done so. As I’ve shown, it’s quite rare for new signings to have excellent first seasons, and especially excellent first halves to their debut season. But either bad luck or bad judgement has left the Reds relying on those who, to date, haven’t really delivered (beyond those individuals having good games here and there).

Whatever went wrong with the summer’s transfer work, I just happen to believe that it’s always a lot more complicated than saying “we should sign world-class players”; which, to me, is a bit like saying “what we should do is win football matches, and never lose them”. It’s too woolly.

What you need to do is sign players who will be world-class (or top-class) for you. But hindsight is a wonderful thing. In 2014, Liverpool signed players believed to have the potential to become world-class, with Markovic and Origi – full internationals for good countries in their teens – plus Emre Can, who played for Bayern Munich at the age of 18, and Javier Manquillo, who played for Atletico Madrid last season aged 19.

I think that this was an eminently sensible strategy. To spend £40m on that quartet is really sharp thinking – as was investing £12m in Moreno (22) – even if we don’t know if they will develop as hoped. But as I’ve shown, buying big-name experienced players rarely gives you the immediate impact you expect, anyway. (It just happens to be a season when Chelsea have nailed their big deals, and Arsenal’s big singing has been a big hit.) To buy five players aged 22 or under for £50m is exceptional business … in theory.

The issue is that the players aged 24-32 – Lambert, Lovren, Lallana and Balotelli – have failed to either get in the team or play well enough for long enough. The odds suggest that at least one of those should have landed on his feet. With injuries to key players, and the sale of Suarez, it probably needed two of the four to make a big immediate impact.

So, are they slow starters, or just not good enough? As ever with transfer analysis, time will tell.