By Mihail Vladimirov

Between 2006 and 2009 I worked in advertising agencies. Each year I moved to a bigger and better one, improving my own level within the company and, naturally, enjoying more money. But mo’ money brings mo’ problems. As you climb the greasy pole you notice the dark side of your job. You learn about the way in which the industry operates (both the positives and the negatives), including the Machiavellian politics and the corruption. When faced with a choice between money and my soul, I chose the latter. However, my medical history, which has since got worse, (I’m an acute asthmatic and am unsuited to physical work) means that since 2009 I have been without a, quote unquote, “proper job”. However, in the past couple of years my condition as a whole improved, due to specific food and training regimes.

There was a lot about my job that I did enjoy, but my main passion since being a young kid has been football. My first strong memories of Liverpool were the matches with Newcastle in the mid-90s, when results such as 3-3 or 4-3 were regular occurrences. At that point I understood why my father had such a passion about this particular club. Before then, I only really paid attention to his glorious stories about the 70s and 80s – Dalglish, Rush, Keegan, et al.

Since then there have been high points – the UEFA Cup run in 2001 was a particular highlight, as was the following season where we finally had a realistic chance of winning the league. But the turning point was when Valencia (managed by some bloke called Benitez) came to town in October 2002 for the Champions League and gave Liverpool a footballing lesson at Anfield. I was shocked but highly impressed by their style of play, and began to pay more attention to Valencia’s games and results, trying to watch them whenever I could. It was such a stark contrast to Houllier’s Liverpool, with the biggest differences being the brand of football and the completely different formation. The gulf between the two sides made me realise the failings of my own team, and made me pay much more attention to the details of tactics on the pitch. Thanks to Rafa.

The failings of the final two seasons under Houillier were the direct result of the failings of the team’s philosophy. Everything – the style, the formation, the way they played – was bound to disintegrate eventually.

Then came Rafa. His appointment and the history of his first two seasons are well-documented. The key moment for me happened at the beginning of the 2007/08 season when he settled on playing the 4-2-3-1 formation on a regular basis. This coincided – although the cause and effect is impossible to disentangle – with the signing of Fernando Torres, which allowed the team to play with a lone striker. It clicked – Benitez was trying to replicate the style of play he had used at Valencia. It peaked in me a curiosity, and I took more time to scrutinise the decisions that were made on the field of play. I watched the movement of the players in different situations, re-watched matches to see what I’d missed, pored over what statistics I could find on the club, and started to learn so much more about the tactical side of the game. In short, football became a different game for me – I needed to watch games in an analytical manner, trying to learn as much as I could about formations, styles and behaviours. It almost became more important than seeing the side win. Almost…

When I quit my job as project manager at the last agency I worked at in November 2009, it neatly coincided with Liverpool’s worst season in terms of their tactical performance and the results in the league during the Rafa’s era. Now I had as much time as I wanted to fully follow, evaluate, examine and theorise about Rafa Benitez and the Liverpool team, comparing details of the best (08/09) and the worst seasons (09/10). During the final moments of Rafa’s final season, I can honestly say that I spent the whole time watching, reading, writing, thinking and, most importantly, learning about everything tactical about the club. I studied the behaviour of the unit and the individual players, and began to understand what Rafa was trying to do.

So, I don’t think it’s hyperbolic to say that I have learned what I know about football from one man – Rafael Benitez Maudes. Even though I have never met or spoken to the man, he has taught me everything about the 4-2-3-1 and his style as a manager. Despite his ignorance of my existence, I was his protégé, he my mentor. This is why I always answer the question “who is your all-time Liverpool legend” unhesitatingly with “Rafa”. For a club that has produced Dalglish, Paisley and Shankly, maybe I’m a heretic. But it doesn’t bother me. I’m not old enough to remember those great men (or, at least, not first time round). None of them had a direct impact upon my life in the way that Benitez did.

Indeed, Rafa is the only person in football I refer to regularly with his given name – imagine how sad I was, therefore, when in June 2010 he “resigned”.

Of course, Hodgson had an effect on me too. He also taught me a lot about tactics. He showed me the key failings of his preferred formation. If you want to know about a particular system you need to know its pros and its cons. From this point of view, Hodgson’s tenure allowed me to become a more knowledgeable writer. But I think I’d rather have been more innocent and naive as an analyst than to have had Hodgson inflicted upon the club. Still, you can’t change what has been and gone; so I will take one dubious “gift” that he gave all Liverpool fans; the gift of seeing the problems that can arise when playing with a 4-4-2.

Someday, I hope to see Rafa in the flesh, shake his hand, and thank him for all that he has – unbeknown to him – taught me. But not quite yet. I was gutted that I couldn’t afford to get across to his event last month due to other commitments.

Rafa versus Dalglish

What I learned from Rafa is a way of thinking. His manic attention to detail, almost pedantic attitude to every aspect of tactics and his perfectionist outlook gave me a lot to look at. It was an opportunity to see in micro detail what was happening on the pitch. What I learned was that you have to try and be fair and objective, knowing that nothing “just happens” – for everything there should be an aim. That aim can be the right or the wrong decision. I also realised that sometimes there are decisions which are hard to understand or to agree with. In those situations, I learned that you need to go away, look at the data, and try to find out if there is a hidden reason or if there is a better decision than can be made. This experience is now helping me to see patterns and the “whys” of the decision-making process. I believe that by starting with Rafa – and then by analysing how other managers go about their business using this way of thinking – I have the tool kit to understand, more or less, how every manager works his vision into the team.

With that tool kit, I want to understand how Dalglish goes about his job – both now and in the past.

Rafa’s tactical record speaks for itself. But we also know that Daglish was one of the most intelligent players in world football. Right now, he is one of the smartest coaches. However, their brains work in different ways.

Being a modern, continental manager, there was no surprise that Benitez spent a lot of time micro-managing his team. In modern football everything is about this level of control and how you can take parts of the game out of the control of the opposition. At the first level, possession is a way in which you can dictate the flow of a game; pressing is a good way of denying teams that comfort. Thus, pressing and possession have become omnipresent obsessions for modern football managers.

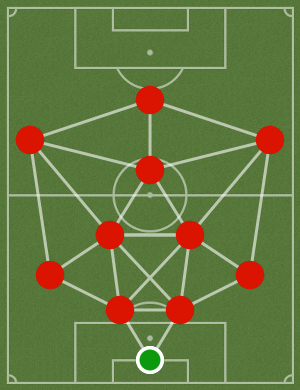

It is also the reason why Rafa spent so much time working on every single aspect of the team. To control a match tactically you need to be able to both attack and defend in such a way that the opposition is stifled. This is why he placed so much import in the 4-2-3-1. It is the most balanced for teams who wish to press all over the pitch because it does not sacrifice defensive stability. Pressing is important for any team wishing to impose themselves on the game, leaving little time for the opposition on the ball. In attack, it creates natural passing triangles which allow the players to pass the ball into open spaces and circumvent opponents anywhere on the field.

The trade-off, to ensure that Rafa’s instructions were followed to the letter, was that the players were given very prescribed roles with little creative freedom. This allowed hard-working, reliable players such as Arbeloa, Mascherano, Alonso, Finnan, Carragher, Riise and Kuyt all to improve dramatically as footballers, impressing in their own particular roles. Others, usually labelled as “flair” players, such as Benayoun had a harder time of things because Rafa believed they lacked the tactical discipline to function within his unit. These were the players most critical of Rafa’s management style, claiming that he did not know how to talk to his employees. Interestingly, Gerrard is one of these sorts of players, but his position in the team was to be the player with the freedom to pull the strings. Indeed, as time went on he was required to do more and more, raising his game to deliver incredible performances. Given his natural ability and his leadership skills – the icon of the club on and off the pitch – Gerrard’s place in the advanced position meant that he was able to express himself. His relationship with Rafa was nowhere near as strained.

The main skill of the coach was to understand how to construct a plan to nullify the threats of the opposition. The tactical victories against Barcelona, Real Madrid, Chelsea, Manchester United and Juventus were not freaks, nor were they down to luck. Despite being the weaker side “on paper”, Rafa’s ‘pedantry’ had instilled a discipline in the side which allowed it succeed. The period in which the team were most exciting to watch – that season, especially in the March-May period of 2009 – was when each of the players knew their roles within the system and so were granted that little bit of extra freedom. The result was devastating for their opponents, as we well know.

Dalglish has a completely different outlook. He was such a creative force in his playing days that even his teammates didn’t know what he was about to do next (although his near-telepathic relationship with Ian Rush seems to suggest that at least someone was on his wavelength). As he is also a British manager, brought up on a diet of “pass and move” from the 1970s and 80s, it comes as no surprise to find that he is a different beast favouring a different formation and style of play. It makes Dalglish more ideological than pragmatic. To win is not enough – The Liverpool Way requires a certain element of honour and class. Who knows that better than Dalglish?

Dalglish requires his players to be given a healthy dose of creative freedom, not only to get the result but also so that they enjoy playing for the club. It is not so long ago that Agger was raving about how much he was enjoying the style of football and the results that Dalglish’s mantra was producing.

Of course, that doesn’t mean the players are free to do whatever they like. To achieve good pass and move football, there needs to be a solid framework with specific tactical instructions. The players need to know who to pass to, where to move once they have passed it, and when to push forward or drop deep. Partially this is so the attacks are structured, but also so that massive gaps don’t open up once the team is forced to defend. All of that needs to be discussed before the players get on the pitch and is developed studiously on the training ground.

For Dalglish, controlling the match means having the ball and creating wave after wave of highly creative, fluid attacks. It means scoring to knock down your opponents and then scoring more goals once their sprit is broken. Rafa used to wait, biding his time to score one more goal than the opposition. For Dalglish, it is important to attack, creating a high number of scoring chances that will, eventually, bring goals as the opponents make mistakes and tire of chasing shadows.

The balance has shifted. Today, the team creates far more chances than it did under Benitez; but it has far less control over those matches.

The rest of this post is for subscribers only

[ttt-subscribe-article]