By Andrew Beasley.

Following my recent piece on the form of opposition keepers, a comment from jameske piqued my interest. To summarise, he pondered whether the bulk of Liverpool’s chances have been in the first half, and so opposition keepers may be doing well through expecting this. Not only that, but if the Reds tire themselves out in the first half, then it may give the opposition the impetus to attack more in the second half.

Watching last week’s match with Chelsea, there certainly seemed to be something in this idea. Not for the first time this season, Liverpool played noticeably better in the first half than in the second; off the top of my head you could easily add Sunderland, Wolves and Norwich to the list too.

Using the Guardian chalkboards, I have broken down each match into fifteen minute sections, to try to see what trends (if any) can be found in the attacking efforts of both Liverpool and their opponents in the thirteen league games played so far. This article may raise more questions than answers, so obviously comments are hugely welcome.

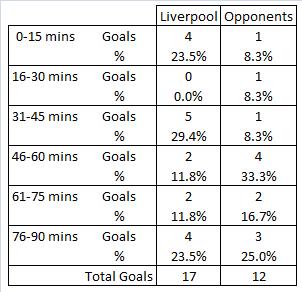

The first stat to notice is the times of the goals scored and conceded. Liverpool currently have an almost even split of nine first half and eight second half goals; by contrast, their opponents’ twelve goals have a nine-three split in favour of the second half. As goals scored towards the end of games inevitably have a greater bearing on the result, this is not good to see.

At Anfield, this issue is even more pronounced – Manchester City became the first visiting team to score a first half goal on Sunday, but a total of five, which have ended up costing the Reds six points, have been conceded after the half time oranges have been consumed. Here’s a breakdown of the goal times:

Aside from the fact you may as well go for your pie between 16 and 30 minutes gone as you won’t miss much, what can we see from these figures?

The most costly period defensively has been immediately following half time, and three of the four goals conceded in this spell have been at Anfield. Are Liverpool slow out of the blocks second half, or are the opposition making tactical changes that have paid dividends?

In three of the games (Wolves, Manchester United and Norwich) a substitute has been brought on in the second half and scored within five minutes of entering the fray, though only Steven Fletcher of Wolves managed to do so after coming on at half-time. Sturridge scored for Chelsea after being brought on at the break too, and he managed it within just ten minutes.

In a season of statistical anomalies for the Reds, the above facts may well represent another. From 36 substitute appearances, Liverpool’s opponents have scored four goals by the men brought on; this equates to one every nine sub appearances.

I haven’t looked into how many goals subs normally score for those teams, as it would take forever and a day, but I do have some research I can draw on. My first piece for The Tomkins Times was an attempt to assess of how successful Rafa’s substitutions were. The research revealed that a substitute scored a goal every 13.9 games under Benitez.

Granted it’s a much smaller sample for this season alone, but again Liverpool have been punished by a seemingly above average goal scoring record by subs. Interestingly, the Reds have a goal by a sub every 14.5 appearances so far this season, so Kenny is close to Rafa’s average on that front.

Let’s break down further from goals and look at total shots. Whilst Liverpool have had 56 more shots than their opponents, in terms of breaking the figures down into sections of the match, the percentages are pretty matched between the Reds and the opposition throughout:

The rest of this post is for subscribers only

[ttt-subscribe-article]