By TTT subscriber Lee Mooney.

How might economics, the ‘right’ data and a team of ‘fanalysts’ put Liverpool FC back on its perch?

‘A journey of a thousand miles starts with a single step’

Lao Tzu, Chinese philosopher

My career to-date has largely been spent helping organisations to find and exploit the value that’s hidden in their data. Generally, to frame initial conversations about projects, I’ve found the following structure to be helpful:

- What is the business question we’re ultimately trying to answer?

- Can we prove/justify why having the answer to that question really matters to the organisation?

- Conceptually, to answer that question, what data would we need?

- How much would it cost to make the required data available in a usable format?

- Do we have the right people, skills and tools to understand the data and create value with it?

The outcome of this exercise is a matrix of ‘questions’ with each question located in terms of cost and value. The next step from this point is to prioritise the various activities and build out a more refined view of scope, timeline and cost. So, at least in theory, your initial areas of focus are those that matter the most and are also those that can be transformed into value the quickest or at the lowest cost (depending on your circumstances).

I’ve come to apply the same thought process to football. What are the business questions that really matter to Liverpool Football Club and can we prove why they matter? What data would we need to answer those questions and how much would it cost to make that data available in a usable format? Finally, and perhaps most crucially, does the club have the right people, skills and tools to understand that data and create value from it?

You can’t assess the significance of a particular question without first understanding the business

There’s a fundamental difference between ‘clubs’ and ‘businesses’. A football club, ultimately, exists to serve its supporters. I guess the easiest way to articulate what supporters want from their football club is to feel ‘part of it’ and to be ‘made happy’. About as subjective and volatile a set of expectations as can be faced I’d imagine!

A football business though is different. A football business exists to deliver value to its shareholders through a return on their investments and the payment of dividends. Delivering those outcomes requires the careful management of revenues, costs and assets to generate profit. It was suggested to me that ‘entertainment business’ might be a more appropriate paradigm to use here – thinking in terms of theaters, award-winning actors and the merciless shifting of high-margin merchandise.

Could it be argued that winning football matches is really just a driver of value in a football business – one of several which can enable shareholder value?

Continuing my sacrilegious journey, let’s think a little more about the Liverpool FC ‘business’ in terms of its revenues, costs and the management of its assets.

Putting football club revenues into context

In terms of income, Liverpool FC is already amongst the top-ten revenue earners in European football. Interestingly, this position is achieved whilst being a relative under-performer in footballing terms (when compared with the other members of that list). I guess the sustained successes of the past has given rise to generations of fans that will take time to ‘fade’ away. Similarly, it will be many years before the recent successes of Chelsea or Manchester City will accumulate into a significant global following.

Thinking open-mindedly, and perhaps with a hint of cynicism, could this be why FSG bought Liverpool FC in the first place? Does Liverpool, because of the ‘stickiness’ of its revenues, represent an ‘easy’ opportunity to grow shareholder value? Consider this possibility: increased shareholder value = avoidance of supporter protests + reduced costs + better use of assets.

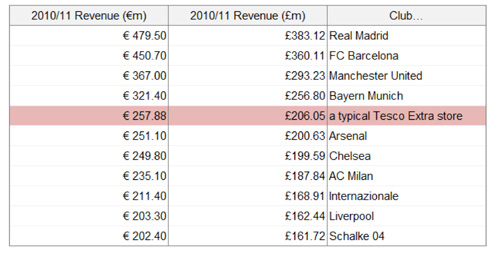

One thing that all fans, and ‘fanalysts’ (possibly a new term which I might have just invented) in particular, need to understand is that football clubs aren’t large businesses at all. A typical ‘Tesco Extra’ store – that’s one single store just to be clear – can generate in excess of £200m per year in revenue (enough to place 5th amongst Europe’s elite clubs, source: Deloitte; Tesco numbers derived from average retail revenue per square meter of retail space for the last financial year):

Now, I’m not saying that FSG should knock down Anfield and build a supermarket, or that they should turn Melwood into a housing development, but you do have to wonder why the ‘smartest guys in the room’ decided to buy a football club at all? Is this a short-term investment, a quick ‘flip’ to make a ‘fast buck’, or is something else motivating FSG? Perhaps, just possibly, they have a desire to achieve in ways other than returns and profitability?

Players are a significant and complex piece of the puzzle

One way to begin understanding a business is to review the balance of its assets and liabilities and put those in the context of the competitive marketplace. Improving the health of a business is basically about getting more value from its inventories, machines, buildings and employees.

I think a football business is a little different though, and it’s different because of one unique element: the ‘players’. The ‘players’ are really employees but they’re also machines and inventory (depending on how you look at it). Managing players effectively, at least in my opinion, is really about finding the right blend of principles from across the social sciences.

Thinking of players as employees is possibly the easiest perspective for most people to relate to. Employees, generally speaking, require a range of environmental factors to be in-place which enable them to perform at their best in the role they were hired to fulfil. For the business, the goal is to continually have the right people in the right roles (either by recruiting internally or externally) and to ensure the headcount numbers and salary costs are carefully managed.

Thinking of players as ‘products’, or different types of ‘assets’, is a little more abstract. Individual players have the capacity to generate revenues through marketing, advertising and merchandising. Some players have immense merchandising value – perhaps far more than their ability to generate value through their playing abilities (see the increase in merchandising revenues for the LA Galaxy following David Beckham’s arrival). I’m not sure if they’re ‘products’ exactly or if this is simply an aspect of their ‘employee’ role that is frequently overlooked. One thing’s for sure: a player’s commercial revenue contribution, above and beyond their contributions on the field, is a variable that needs to be considered in the recruitment decision.

I find the ‘asset’ perspective possibly the most interesting of the three. From this view-point, players are like inventory, or cogs in a machine (good teams are often described as ‘machines’). Players basically need to be acquired, maintained, replaced and disposed of with ruthless efficiency. As inventory, players effectively exist within a football business to be re-sold. As cogs in a machine they’re really no different to parts on your car – they have a service interval, a maintenance schedule and patterns of usage which can either prolong or shorten their life. They need to be replaced in good time as their degradation can cause damage to other parts of the machine.

Which business questions should matter the most to football clubs?

The owners and managers of Liverpool FC will make hundreds of decisions every day – so, which decisions are the most important ones to get right? Surely it’s the questions underpinning these decisions that need to be the most well-informed – and therefore the focus of the ‘fanalyst’ community (if we want our efforts to have a positive impact)?

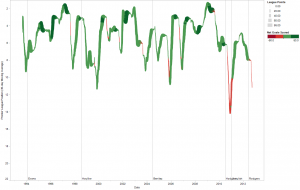

My personal opinion is that player trades and wage decisions matter more than all the other decisions combined. Throughout the club’s history, we’ve grown when we’ve traded well and we regressed when we’ve traded poorly (also available interactively via the embedded link: http://tinyurl.com/c5k3n24):

Obviously other factors play a part. But, I personally don’t think incredible coaching, tactical acumen or motivational ability will ever compensate for the loss of £40m in value resulting from poor purchases or sales. Such write-offs, particularly when your rivals don’t have to make them (or are successfully pumping in even more money), are just too big a hit to absorb. Sadly, Liverpool fans know this better than most…

Rafael Benítez was (and is) a top European coach with a proven track-record of winning at the highest level. His systems and techniques were well-established at Liverpool FC over a period of six years. In his final year, despite all the meticulous attention to detail and the proven elite coaching and tactical acumen – capabilities that delivered Liverpool FC to the pinnacle of European football – it was restrictions on player trading at crucial moments that broke his regime (and broke it fast). This decline was accelerated by the Roy Hodgson regime and was compounded further during the Comolli/Dalglish era (where good players were bought but for fees clearly calibrated against those being paid by clubs like Chelsea and Manchester City rather than Arsenal, Everton and Newcastle).

Opposite to the above example is Alan Pardew’s time at Newcastle. A succession of excellent transfer deals in a short space of time effectively propelled Newcastle – a club only recently promoted and having just sacked a manager – into the upper echelons of the Premier League.

Player wages generally account for 50% to 70% of turnover – if you add in the value of players sold and bought then you’re talking about a massive overall ‘impact’ given the size of the business. The conclusion then: the following ‘big questions’ can effectively set the operating level of the club for a number of years:

- Who are the right players to buy/sell?

- When is the right time to buy/sell these players?

- What is the right price to buy/sell these players for?

The last of these three questions is really what separates the winners and losers for me. It’s not enough to just buy good players, you need to be paying fees and wages in-line or lower than your rivals (obviously excluding those clubs that have a sugar-daddy). Arsenal, Newcastle and Everton currently set the standard in my opinion. Newcastle last 2 years in particular highlights this key point really well in my opinion. The price you pay is so important – the right price means you can ‘live to fight another day’ when you make a mistake and need to sell that player on.

With these critical questions identified, and the reasons for highlighting them explained, I’ve quickly come to challenge the value of my own ‘fanalyst’ contributions to-date. Too much time has been spent thinking about performance analysis and tactical content. Looking at the bigger picture logically, I’ve come to conclude that this content really doesn’t matter that much. Here’s some more detail to help explain why.

Performance analysis doesn’t matter much in the big scheme of things

The ‘on-ball event’ data is pretty much used by everybody in sports journalism and analysis. Surely it’s an accurate record of the events that matter in a football match? Surely understanding this data is the key to unlocking new levels of understanding and insight? Maybe, just maybe, it’s not the ‘goldmine’ of insight that many think it is.

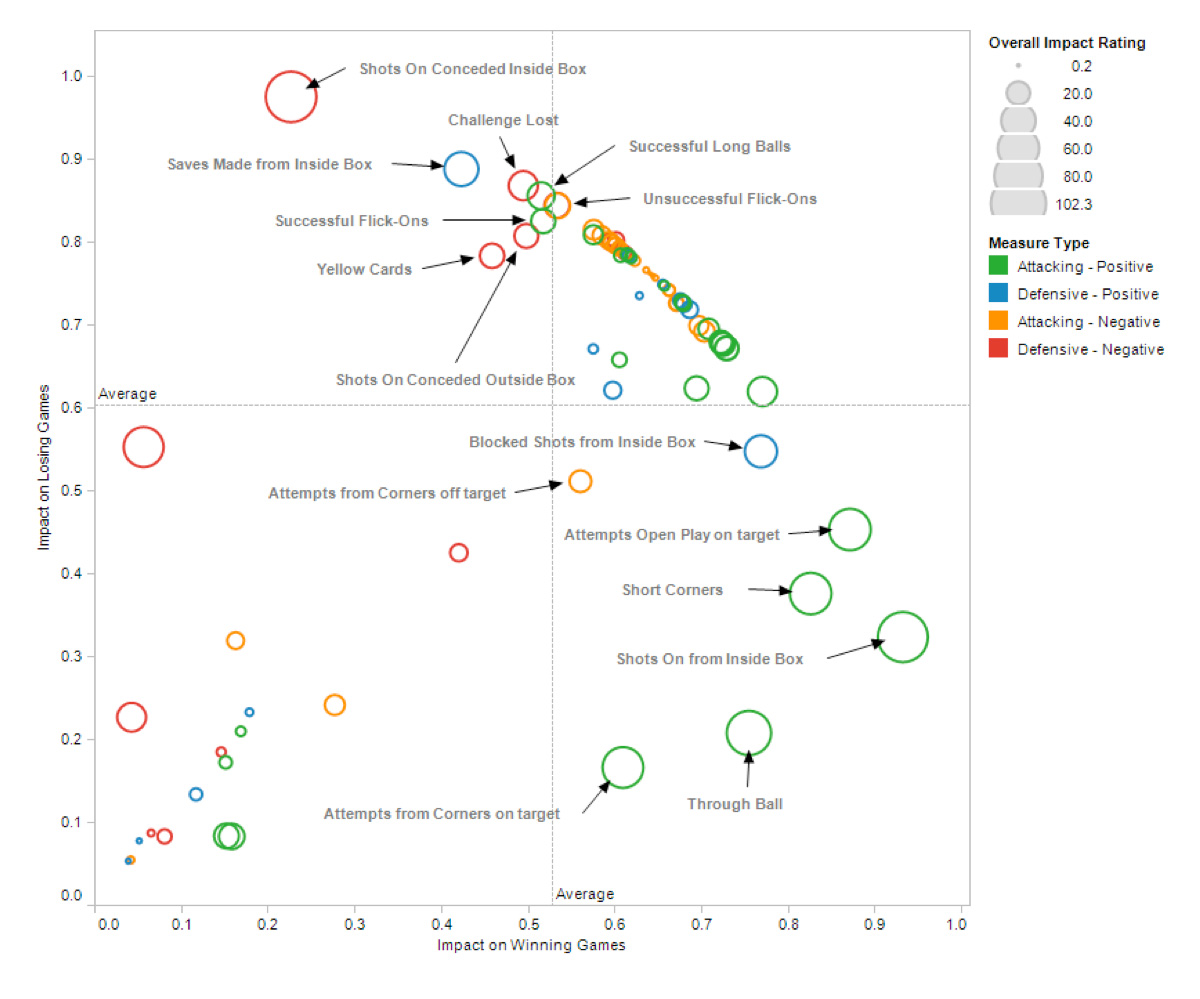

On-ball event stats capture 193 measurable events during a game for each player involved. My extensive analysis of this data, requiring many thousands of individual calculations, is presented in the visualisation below (also available interactively via the embedded link: http://tinyurl.com/92y4uxb):

[PT: I think this is a work of art. Once you get your head around how it works, it’s an incredible graphic. Be sure to click on the link for the interactive version, which fills the screen and allows you to select any of the circles for an explanation.

Using Lee’s interactive graphic, I have created my own illustration to show how direct game tactics – successful long balls, successful flicks ons and successful crosses in the air are grouped in a very mid-range band in terms of their impact on winning games, and also their lack of impact in avoiding losing games.

By contrast, approaches that you’d associate with cultured football – short corners, successful dribbles, successful final third passes and successful through balls – are in the areas of the graphic you want to see them: lower down, and further to the right.]

Teams that win tend to dominate their opponents in terms of:

- shots on-target inside the box

- use of the through ball

- attempts on-target from open play

- short corners played

- attempts from corners on target

Teams that lose tend to dominate their opponents in terms of:

- shots on-target conceded inside the box

- challenges lost

- use of the long-ball and flick-ons

- yellow cards

- shots on-target conceded outside the box

So, games are largely won or lost as a result of key moments in and around the penalty box. There’s little evidence to suggest that passing better in any area of the field directly results in wins unless that pass is a through-ball. What really matters is what you do with the ball in the vital areas (or when trying to penetrate those vital areas). Could it be that the current Liverpool philosophy places too much emphasis on the general dominance of possession? How strong is the relationship between possession and winning? Perhaps one for Brendan Rodgers to think about…

The availability of data, and ability to analyse it in this way, might be modern – but is this new knowledge? Could it be that this generation has forgotten the early lessons of those managers that pre-dated the ‘data era’ and perhaps what we’re seeing now is the rediscovery and re-learning of old lessons via new means? Could the drive for footballing ‘modernity’ actually be damaging, rather than improving, decision-making?

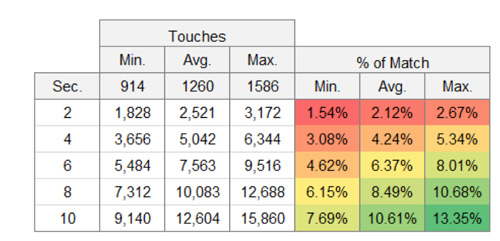

Let’s put this ‘on ball’ data into context. A football match is 22 players contributing (excluding stoppages) 90 minutes of output each – so 118,800 collective man-seconds are spent in every encounter.

Last year there was an average of 1,260 ‘touches’ on the ball in a game (maximum of 1,586 and as low as 914). Considering a range of values from 2 seconds per touch to 10 seconds per touch, ‘on ball’ activity only accounts for as much as 13.35% of the overall contribution and as little as 1.54%.

If the ‘fanalysts’ are to have an impact then we need to focus on identifying the ‘right’ data for the ‘big questions’. Thrashing the data available is leading some of us to lose a bit of perspective – we’re also potentially ignoring a huge proportion of what’s actually happening in a game. From now on I’ll be focusing much more on how players acquire and deny space, how they move and the intelligence of that movement in-relation to the other players on the field.

If a football match is so much more than the ‘on ball’ events, with the margins between winning and losing in those terms being very small indeed, what are the big differentiators? Does one ‘style’ of play really dominate the other? Clearly aimless long-balls and flick-ons aren’t a durable platform for success, but other than that? Surely if you can get the ball into the box quickly to someone who’s ruthless at putting it in the net, whilst giving away nothing at the back, then surely you’ll do OK – could Sam Allardyce actually be smarter than many give him credit for?

I’ve heard accounts from ex-Liverpool players who played for both Paisley and Shankly. They described managers who bought ‘footballers’ to their teams – players who were smart enough to modify their style of play when faced with a situation. These weren’t players that slavishly followed a script – they read the play and made the right choices as a unit. They were expected to solve problems themselves. What data would enable objective analysis of these characteristics and does it exist? I’m not sure it does.

The exploration of ‘off-ball’ event data is possible today via camera systems like Amisco. Such systems increase the amount of information collected per game from approximately 2,000 events to around 4.5m pieces of information. However, analytical costs increase with increases in data volumes and data complexity. This is especially relevant given the size of football businesses as analytical tools and large-scale data handling capabilities can be expensive. The potential of exploration to deliver new insight needs to be balanced against the costs of those potential discoveries.

I suspect football clubs will rely upon packaged software offerings to manage the presentation of information from these large sets of data. If this is true, then this means that any rival who’s bought the same product will know everything you know – so what’s the point other than to keep pace? How should Liverpool FC use data to achieve competitive advantage whilst operating within the boundaries of financial viability? My recommendation would be – at least as far as the ‘big questions’ are concerned – would be to look away from packaged software and towards some smart innovations using data that is overlooked because it isn’t ‘reassuringly expensive’, a kind of ‘Moneyball’ for data so to speak. For example, the piece I did earlier this year (Solving Liverpool’s Goalscoring Woes) was developed entirely using free data from Wikipedia and other free web sources.

Achieving competitive advantage whilst operating within the boundaries of financial viability

“It’s the economy, stupid”. If you’ve got something worth buying, a bigger club will eventually come along and buy it from you. Sustained success then, sadly, is all about the economics – so it’s in the economics that clubs should seek to gain or cement an advantage.

If ‘fanalysts’ are to have the impact on the club then we need to turn our collective energies to the three ‘big questions’:

- Who are the right players to buy/sell?

- When is the right time to buy/sell these players?

- What is the right price to buy/sell these players for?

Manchester City FC has led the way in terms of engaging with its ‘fanalyst’ community to harvest usable insights in a low-cost way. However, by focusing on the ‘on-ball event’ data, I don’t think they’re harnessing that energy in the most valuable way. Perhaps Liverpool FC can do things differently and take the lead?

In any case, a key priority for FSG should be, in my opinion, the building of an enduring capability that is the best in the business at answering these ‘big questions’. This capability should be on the permanent pay-roll and have enduring principles which are embedded deep into the ‘constitution’ of the club. Such a vital capability has to be built within the organisation and endure despite changes in management. Managers should be appointed with their first duty being to honour and preserve that constitution.

For example, if Liverpool’s constitution had strict standards for passing and control ability – would they have hired Ryan Babel? Would tests of attitude and character have let El Hadji Diouf through the Shankly Gates? If Bob Paisley’s view that ‘legs should go on someone else’s pitch’ was still enforced, would we have hired Poulsen, Konchesky or Cole (or still have Gerrard or Carragher playing regularly)?

Modern managers operate in the face of intense short-term scrutiny. Success, sadly, is also measured on the same timeline. I believe that genuine understanding and insight is being drowned out by the noise of 24/7 talk radio, media hype and cheap ex-player punditry. It’s easy to see why many managers might just ‘play it safe’ and aim to acquire household names or adopt a ‘reassuringly expensive’ approach to transfers – the ‘short-game’, for many, is the only game worth playing.

Personally, I’m often encouraged when we’re linked with players that the vast majority of fans haven’t heard of. I’d also actively welcome a ‘panning for gold’ strategy that quickly filtered through potential ‘rough diamonds’ that we’d bought cheaply. Data can help to identify these opportunities and to ensure that the fees being paid are properly calibrated. Sometimes it will mean walking away, and taking some heat from the fans, but that’s what real leadership is all about – it’s not a short-term popularity contest.

According to Albert Einstein, “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted”. When you think about these ‘big questions’, what really matters and can these elements actually be counted?

The autobiography of Brian Clough identifies a number of desirable player characteristics. These characteristics are introduced by first emphasising that player recruitment is “vital” to success and that managers should invest carefully and with skill (10 years later, the available data is now able to support that message):

- ball control is ¾ of challenge – must be automatic

- teams must have real talent in goal, at centre back and striker

- confidence with the ball

- bravery, courage and no fear

- discipline, respect for referees

- familiarity and comfort in their role

- smart enough to handle your tactics

- everyone gives everything to the team

An objective assessment of some of these qualities is totally possible. I expect it would be difficult to assess these qualities from afar though using secondary data. But, an assessment centre environment that creates primary data could work. Many organisations use this method today in recruitment, so why should football clubs be any different? However, some of these items are also abstract and as such would be almost impossible to quantify. That said, perhaps they’re not impossible to engender through the right processes and systems? When you look at Cuban boxing, the Chinese approach to Olympic sports and Barcelona’s ‘La Masia’ academy – you see three ‘systems’ that are all highly capable of transforming people and delivering a required level of capability.

The same ‘data guided’ approach could be turned to Liverpool’s youth development. Imagine, as a youngster, if Liverpool FC had operated an ‘open-door’ talent policy. You could put yourself forward at any time for assessment with a view to getting into the club and ‘unlocking’ further opportunities and support. If you passed, you’d be one step closer to the team. If you failed, you’d get objective feedback so that you knew exactly what needed improving and how you could do it – the door always remaining open. What kind of players would this approach introduce? Now…imagine then extending a proven model of this type on a global scale – avoiding all of the restrictions on catchment areas and the ‘ivory tower’ Elite Performance Plans (which will limit access to those children who’s families can afford to support the logistics associated with that).

This is just one idea from one ‘fanalyst’. Can you imagine the creative and practical potential of the wider community if it was engaged effectively? To move forward, I would encourage Liverpool FC to really engage with the ‘fanalyst’ community and set it challenges in five key areas:

- player life-cycle tools (buy – use – sell);

- youth development initiatives;

- new wage and incentive models;

- financial ratio analysis of competitors; and

- innovations that open up new revenue streams or increases in existing revenues