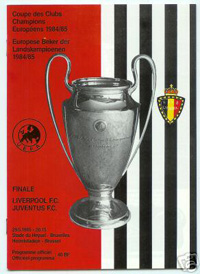

This is an abridged version of the final chapter of From Where I Was Standing, Chris Rowland’s tale of the trip to Brussels with his usual collection of match-going mates, and how events, after a care-free journey, took a turn for the worse.

Chapter 10

IN CONCLUSION

In the days and weeks that followed, Heysel continued to dominate the news. From the newspapers to TV chat shows to the House of Commons, it was just about the only topic of debate. A few days later, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher pressured the FA to ban all English clubs from Europe indefinitely. Our own Football Association had pre-empted them by withdrawing our clubs from the following season’s European tournaments pending UEFA’s announcements. Two days later she was granted her wish as UEFA banned all English sides for what they stated was “an indeterminate period of time”. Liverpool received an additional ban of “indeterminate plus three years”, or more precisely, three further years in which Liverpool qualified for European competition. If they didn’t, the ban would roll on until they did. Given Thatcher’s previously stated dislike of the city of Liverpool –– probably because of its left-wing politics and strong opposition to her government and philosophy –– and her very apparent dislike of football and football supporters generally, we hardly expected any help from her. It was the excuse she and her cronies had been looking for to put the boot into football just the way they had with the miners.

She and the Queen issued formal apologies to the people of Belgium and Italy. That must have helped. Liverpool Football Club itself would have been justified in feeling harshly treated; it had done all within its powers to control its own supporters, and sold no tickets for the ill-fated Block Z. It was not the club’s fault that some other agency fatally did so, nor that some of its supporters could not resist a punch-up. Liverpool FC also had no part in the decision to stage a major match at Heysel in the first place; indeed Liverpool’s secretary Peter Robinson urgently requested that UEFA move the final to a more suitable and safer venue, but his plea was ignored. Neither was the club responsible for the appalling condition of the Heysel Stadium, the inadequate supervision outside it or the supine inertia of the authorities inside it. Above all, Liverpool FC had good reason, based on precedent, to trust its supporters.

In the end, the ban on English clubs competing in Europe ran for five years, with Liverpool’s extra three years reduced by two. As English clubs had dominated the European Cup in the eight seasons before Heysel, winning it seven times (Liverpool in 1977, 1978, 1981 and 1984, Nottingham Forest in 1979 and 1980, and Aston Villa in 1982), this left a considerable hole in Europe’s most prestigious football competition. It took until 1999 for an English club to win it again, with Manchester United’s victory in Barcelona. That long gap was Liverpool’s fault too, apparently, because all our clubs had to catch up again after the ban that Liverpool caused.

In the end, the ban on English clubs competing in Europe ran for five years, with Liverpool’s extra three years reduced by two. As English clubs had dominated the European Cup in the eight seasons before Heysel, winning it seven times (Liverpool in 1977, 1978, 1981 and 1984, Nottingham Forest in 1979 and 1980, and Aston Villa in 1982), this left a considerable hole in Europe’s most prestigious football competition. It took until 1999 for an English club to win it again, with Manchester United’s victory in Barcelona. That long gap was Liverpool’s fault too, apparently, because all our clubs had to catch up again after the ban that Liverpool caused.

So Liverpool’s “punishment” was only an extra season’s ban beyond that of the other English clubs that qualified for European football. But in truth the ban was the bill English football had to pay not only for Heysel but for over a decade of violence by English football followers, in which Liverpool’s supporters actually played very little part. Incomprehensibly, the English national team, the epicentre of more exported hooliganism than all the individual clubs put together, was never banned, and was still allowed to participate in international football in Europe. So the very same fans, the very same individuals, whose clubs were banned had only to trade their club colours for their country to be able to roam the continent freely and legitimately following England. The inconsistency of UEFA’s decisions extended to the remarkable leniency shown to Juventus for the considerable part played by their supporters in the disturbances at Heysel. Their ”punishment” was to begin the defence of the trophy they won in Brussels by playing their home European Cup games the following season behind closed doors. Hardly hard line. The point was made that Juventus’ fans had no particular ‘previous’ before Heysel; true, but neither did Liverpool’s.

But such was the prevailing terrace culture of the mid-’80s, with violence endemic in and around football grounds throughout England, and such was the level of antagonism surrounding English football at the time, that a major crowd disaster was bound to happen somewhere, sometime. In Fever Pitch, Nick Hornby puts it this way:

‘The kids’ stuff that proved murderous in Brussels belonged firmly and clearly on a continuum of apparently harmless but obviously threatening acts –– violent chants, wanker signs, the whole, petty hardact works –– in which a very large minority of fans had been indulging for nearly 20 years. In short Heysel was an organic part of a culture that many of us, myself included, had contributed towards.’

A series of goodwill gestures and well-intentioned wound dressing between the two clubs and cities followed –– memorial services in Liverpool and Turin, exchange visits between the two cities, the possibility of a friendly match in Turin between the clubs. British and Belgian police forces swapped intelligence and photographs ad infinitum –– you couldn’t pick up a newspaper or switch on the TV without seeing a circled “wanted” face. The Belgian government creaked under the weight of questioning and accusations of gross incompetence, and, fatally holed below the waterline, eventually sank. Meanwhile its British counterpart, Thatcher’s hang ‘em flog ‘em brigade, maintained a continuous stream of anti-football, anti-Liverpool invective, threatening draconian crowd control measures, the introduction of identity cards and probably the reintroduction of National Service and the death penalty, the compulsory sterilisation of Liverpool mothers or the ritual slaughter of their first-born. Scapegoats were in huge demand, and the slavering tabloid press led the hunt voraciously, revelling in its self-appointed role as the Voice of Reason whilst displaying absolutely none, and the licence Heysel appeared to give it to rant unchecked in an orgy of self-righteous bigotry. Balance and reason, it seemed, had no part in this public “debate”.

A series of increasingly bizarre and surreal conspiracy theories began to emerge in the wake of Heysel; there were reports of extremist right-wing groups having been present, claims that swastika flags and banners and far-right propaganda had been found amongst the debris. There were some suggestions that these may have belonged not to British but Italian fascists who had been there to agitate. It would certainly be difficult to imagine stonier ground for right-wing dogma than the vast bulk of Liverpool supporters, whose red allegiance was not confined to football. Their politics, and the city they come from, inclined sharply towards the left.

The very day after the disaster, UEFA’s chief observer, Gunter Schneider, stated, “Only the English fans were responsible. Of that there is no doubt.” He said ‘English’ fans, not solely Liverpool fans, because several Juventus supporters who were at the game had claimed that there were supporters from many British clubs, including Chelsea. Not quite as unfeasible as it may sound; Chelsea stood to gain from a Liverpool victory –– or a Liverpool ban –– as they themselves would then qualify for European football the following season. Besides, a European Cup Final in Brussels would make an attractive, possibilities-packed Bank Holiday week alternative for a Londoner, just a short and easy hop across the water and barely further than Brighton, Southend or Margate.

The very day after the disaster, UEFA’s chief observer, Gunter Schneider, stated, “Only the English fans were responsible. Of that there is no doubt.” He said ‘English’ fans, not solely Liverpool fans, because several Juventus supporters who were at the game had claimed that there were supporters from many British clubs, including Chelsea. Not quite as unfeasible as it may sound; Chelsea stood to gain from a Liverpool victory –– or a Liverpool ban –– as they themselves would then qualify for European football the following season. Besides, a European Cup Final in Brussels would make an attractive, possibilities-packed Bank Holiday week alternative for a Londoner, just a short and easy hop across the water and barely further than Brighton, Southend or Margate.

The lack of ticket control at the ground certainly made it impossible for the authorities to know who was in the ground and where; here’s an account from a football website –– though not a Liverpool one:

“It was impossible for police to weed out known troublemakers, and easy for pockets of hard core hooligans to assemble wherever they wished. As a result, two hours before kick off, perhaps the most malevolent assembly of football supporters ever seen in one place had gathered, and as far as they were concerned, it was payback time (for Rome 1984). It should be understood that not just Liverpool hooligans were present. There were contingents from a great many firms all over the country, from Luton MIGS to Millwall Bushwackers, West Ham ICF and Newcastle Toon Army. After the events in Rome, club rivalries had been put aside: Juventus were to catch the full fury of the English hooligan elite. There was a score to settle.”

The Heysel disaster’s capacity to fire the imagination reached its nadir when, in April 1986, nearly a year later, a typed, unsigned letter bearing a Los Angeles postmark was received by The Guardian newspaper in London, claiming that the whole tragedy of Heysel had been a “mafia-inspired conspiracy” to blacken the name of soccer and so further the worldwide expansion of American football. “Italian Americans,” it said, “mingled with the Juventus supporters to provoke trouble; Liverpool fans, and English soccer in general, took the rap.” Well the last bit was undeniable; but the theory sounded more like a plot for a paperback and the product of an over-fertile imagination.

All I can say is that none of these things were witnessed by any of us. Although it did not feel quite like the usual Liverpool crowd that fateful evening in Brussels, and much as though we would love to be able to shed some of the responsibility and have it shared by Chelsea or any other club’s fans, right-wing extremists or the Mafia, the fact is that when twenty six names to be charged with manslaughter were released, most had Merseyside addresses.

The release of those names triggered a protracted period of legal jousting and bumbling as the process leading to their extradition degenerated towards farce. It wasn’t until late in 1987 that the accused were finally taken to Belgium to face trial, after over two years of waiting to have their fates decided. It seemed that everything connected to the Heysel, even afterwards, had to be tainted by incompetence.

The ‘Official Reports’ season duly began. Firstly, the Popplewell Report on crowd safety and control at sports grounds, already commissioned by the UK Government pre-Heysel, had its remit widened to incorporate a specific study of Heysel. Published in January 1986, it acknowledged that the first crowd disturbances at Heysel had in fact occurred at the other end, where the main body of Juventus supporters stood, as they clashed with police. This, the report stated, led to English fans firing flares and throwing stones into the mostly-Italian crowd in Block Z –– an observation so at odds with what the ranters in Government and media preferred to believe that they ignored it completely. The report went on:

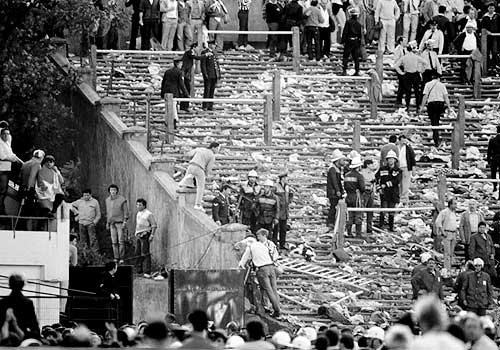

“Between 7.15 and 7.30pm, English fans charged Block Z. There were three charges, the third resulted in the Italian supporters in Block Z, who were seeking to escape, being squashed and suffocated. Everyone knows that those guilty of the violence, those responsible for the deaths of the victims, are the violent groups amongst the English supporters.”

“Between 7.15 and 7.30pm, English fans charged Block Z. There were three charges, the third resulted in the Italian supporters in Block Z, who were seeking to escape, being squashed and suffocated. Everyone knows that those guilty of the violence, those responsible for the deaths of the victims, are the violent groups amongst the English supporters.”

The report acknowledged the poor condition of the stadium and the failure of the police to intervene quickly enough or take adequate action, and added, with masterly understatement, that “a ban on the sale of alcohol outside the ground was not enforced”. Indeed it wasn’t.

By November 1986, after an 18-month investigation, the dossier of top Belgian judge Mrs Marina Coppieters was finally published. In sharp contrast to the one-sided version of events on this side of the Channel, it concluded that perhaps blame should not rest solely with the English fans, but instead should be shared by the police and football authorities. Several top officials were incriminated by some of the dossier’s findings, including police captain Johan Mahieu, who had been in charge of security on May 29th 1985 and was now charged with involuntary manslaughter.

That bears repeating: the police captain who had been in charge of security at the Heysel Stadium was charged with involuntary manslaughter. How many anti-Liverpool ranters over Heysel are aware of that? Then again, many of them weren’t even born at the time, but just accepted their own club’s fans’ warped view of it.

We had known all along that without significant other factors, there would have been no deaths, no major news story, just a minor routine pre-match skirmish followed by a game of football. That somebody somewhere had finally acknowledged it brought huge relief.

There is no doubt that events at Heysel Stadium amounted to a disaster without parallel for European football. Neither the Ibrox or Bradford disasters that preceded it, nor Hillsborough that was to follow, though all involved loss of life, had crowd violence at their core. In football terms they were also purely domestic affairs, with no pan-European dimension.

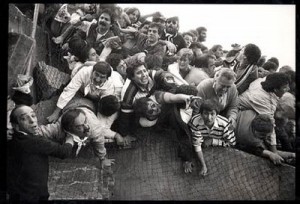

It has become the accepted version of events that the Heysel stadium disaster was solely the result of hooliganism and rioting by Liverpool fans. Yet none of the 39 victims lost their lives as a result of being beaten, kicked, stoned or stabbed. And none who fought and sought to intimidate and subjugate did so with murder in mind or with even the faintest notion of what was about to follow. Perhaps only an architect or engineer could have foreseen those. Even describing the skirmishes at Heysel as ‘rioting’ would be misleading. Judged by the standards of the time, or indeed any time, what Heysel actually witnessed was nothing more than a token bout of territorial terrace ritual involving some fist-flailing and air-punching during which few blows were actually landed and from which few injuries resulted. On any other day it would have led to nothing more than the odd bloody nose or black eye, a bit of tut-tutting from onlookers and commentators, with the whole episode of minor scale pre-match disturbance completely forgotten and unreported as soon as the game got underway. Some missiles were thrown –– in both directions –– and several charges across the terracing occurred. Threatening and unpleasant behaviour, but wholly unexceptional at that time, and only possible because it was made possible. Nowadays it wouldn’t be.

But then a wall collapsed and changed everything. Ultimately, what converted an unremarkable skirmish into a fatal tragedy, what transported Heysel from the mundane to the extraordinary, was not the scale or degree of savagery but decaying cement, a structural defect, the final executioner not hooligans but the crumbling, decomposing perimeter wall of Block Z. The wall, no more than four feet high and twenty feet long, was more than 50 years old, its cement cladding crumbling away from the rotting brickwork. Its obscene result was 39 fatalities.

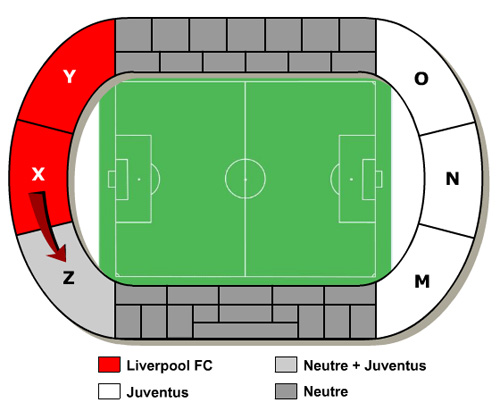

Hooliganism was only the penultimate link in a long chain that stretched right back to our first sight of the match ticket, in that Coventry pub on a Monday evening a full nine days before the match, when we first saw that portentous blob overprinted across the letter Z. To us, it clearly signified that Block Z would be either empty or occupied by neutrals, for crowd segregation purposes. That’s how it always was in England and Europe at the time, for every single game, with rival fans segregated and empty buffer zones between them.

But instead, 5,000 supposedly “neutral” tickets for Block Z were placed on open sale in Brussels. On the morning of the day that they went on sale, they were all gone. Inevitably and utterly predictably, most found their way towards Brussels’ substantial local Italian population or to Juventus supporters back in Italy, after large blocks of tickets had been bought up by Italian travel agents and ticket touts, with very few falling into neutral local Belgian hands. The open sale was halted when this became apparent, but too late. They were sold or sold on to the people who were to die. That was the first link in the chain, and when the tragedy of the Heysel Stadium really began. The Belgian football union, which organised the match, had taken the decision to sell those tickets rather than allocate them to the two finalist clubs, to increase its profits from the game. Anyone involved with football would have known what was going to happen to those tickets beforehand, it was blindingly obvious. As the Popplewell Report confirmed:

“… some organisations bought large quantities of tickets … by using their employees to take it in turns to go to the ticket windows. A large number of tickets for Block Z came into the hands of Juventus fans.”

So the stadium management and presumably UEFA and the local police, knew in advance that Block Z, the block immediately adjacent to the main body of Liverpool supporters, would be neither empty nor neutral, but occupied by rival supporters. They already knew that. You don’t have to be a genius to work out the potential danger of such an arrangement. So wouldn’t you reasonably expect, given this advance knowledge, that Block Z would be strongly policed and segregation rigidly enforced? Instead there was no gap at all between the two sets of supporters, no empty buffer zone, and just a flimsy stretch of chest-high chicken wire between them, unable to withstand any attempt to breach it and guaranteed not to deter one. And the police presence in that area of the ground? When the exchanges between the rival sets of fans began, there were “five policemen and two dogs” separating the crowds, which would sound laughable if the consequences hadn’t been as they were.

Even then, after those initial exchanges, when the potential problems had made themselves all too clear, there was still no response, either from the handful of police present in that area or more tellingly, from the police control (I use the term loosely) operation at the stadium. That would have been the obvious time and opportunity to send in numbers, restore order and separate the two sets of fans with an armed human barrier. It certainly would have happened in England. It later transpired that that the police in Block Z had been poorly trained, strictly third division, ‘the bottom of the basket’ as the French phrase has it. Nor was there a police command centre in the Heysel Stadium to coordinate response, and besides, police radios weren’t working anyway, to compound their inability to react to the situation. Furthermore, the officer in charge of policing had not attended any of the planning meetings before the European Cup Final. In short, the police operation was an utter shambles, which explains why the officer in charge received the involuntary manslaughter charge.

In summary, none of the usual factors to prevent or discourage confrontation was in place. As British police forces responsible for crowd control at English football matches will confirm, these are basic precautions. The control and planning at Heysel fell shamefully short of the most elementary requirements, and amounted to a dereliction of responsibility that made effective crowd segregation impossible. The then secretary of Liverpool FC, Peter Robinson, said:

‘From day one I was concerned about this neutral area. I argued all along that we should have one end and Juventus the other. We suggested there should be a meeting between the two clubs but the Belgian authorities said no. There were serious planning mistakes. That doesn’t excuse what happened, but the problems would not have occurred if it had been done in a different way. It could all have been avoided.”

Short of withdrawing from the match because of their concerns, there was little more that the club itself could have done either before, during or after Heysel.

Long before the day of the game, many concerns had been expressed that the ground was unsafe. When Arsenal had played there several years previously, their supporters had complained about how dilapidated the stadium was. Built in the 1920s, the Heysel Stadium was quite possibly the worst venue in the world to host such a volatile encounter. The game was due to be the last match ever played at the ground, as it had been condemned many years previously for failing to meet modern standards of safety and design. As a result, little money had been spent upon it, and large parts of the stadium were crumbling.

When ordered by the judge to survey the disaster scene, leading Belgian architect Joseph Ange concluded:

“… areas reserved for standing room [including the ill-fated Block Z] remain as they were at the time of their construction in 1930. They are in an advanced state of decay. Only the hand-rest remains on most of the handrails, most are unstable and several on the point of collapse. The handrails were quickly and easily destroyed by the pressure of the crowds, which had no proper means of escape. Concrete terracing was eroded and, crucially, neither the barrier between Blocks Y and Z nor the wall in Block Z were strong enough to resist crowd pressure.”

A London council surveyor sent to the stadium after the tragedy confirmed that there was no way in which it would have been allowed to operate under British regulations. Hans Bangerter, then general secretary for UEFA, criticised the police, though not UEFA themselves of course: “The disaster would not have happened if our specific instructions on security had not been so badly disregarded by the Brussels police and especially the gendarmerie. The English vandals would not have been able to perform such terrible deeds and create such misery if they had not been helped by the frightful incompetence of the Belgian security forces.”

Nor if your organisation had selected an appropriate venue in the first place and not ignored advice and even pleas to switch it, Mr. Bangerter.

This article appeared in the News on Sunday on July 12 1987:

“I went to the Heysel Stadium in the autumn of 1984 –– about six months before the disaster –– for a World Cup qualifying match. I remember only too well the reaction of myself and my friends upon entering the stadium; it was an absolute disgrace. Rickety safety barriers, crumbling walls, ancient terracing, non-existent facilities: a recipe for disaster if ever I saw one. Of one thing I am certain; if basic safety checks had been made and proper segregation been enforced, that wall would not have collapsed and those people would still be alive now. That stadium would have been unfit for a women’s institute convention, never mind a European Cup Final. And as far as the received wisdom that all the trouble was caused by Liverpool fans –– I remember vividly the Italian thugs with their fascist flags and their ‘Reds are Animals’ banner, the guy with the gun, the stick-throwing mobs … and above all, I remember the total impotence and incompetence of the Belgian authorities who stood by while a full scale riot took place, completely and utterly unprepared. A number of Englishmen, not all from Liverpool, behaved like evil scum. They should be extradited and dealt with in the severest possible manner by the Belgian authorities. But it is my contention that the blame should be shared by the Italian thugs, and by the Belgians themselves. We should never forget what happened in Brussels. But it’s time we threw off the guilt, which is not all ours by any means.”

It was also reported that, “… while it is true that the stadium was in abject condition, that Juventus’ supporters found their way into a supposedly neutral section at the Liverpool end, and that local police inflamed the situation, the fact is that without these antagonistic charges, nobody would have died.”

Well, you could just as easily turn that around. Had the stadium not been in abject condition, had Juventus’ supporters not found their way into a supposedly neutral section at the Liverpool end, had local police not inflamed the situation, nobody would have died either. It took all those factors to be present for the tragedy to occur, you can’t just highlight one over another because it suits your purposes.

Yet despite all the concerns about the Heysel Stadium’s unsuitability as a venue for a match of such magnitude, and the ticking time bomb of ticket distribution in Section Z, UEFA still refused to amend their decision that this outdated and universally condemned stage was suitable and safe for Europe’s showpiece football match between two of Europe’s most passionately-followed teams. In doing so they were taking a dangerous and highly irresponsible risk. They gambled and lost, and blamed somebody else.

Poor crowd control and segregation and a stadium in appalling condition is a potentially lethal combination. As a result of the ticket selling arrangements and the decision to overlook the ground’s poor condition, 50,000 people were in danger without realising it, before they even left home. These elements were already swirling in the ether long before the day of the game itself; all it would take for the final link in the chain to be joined was a couple of other factors, notably the failure to enforce an alcohol ban and the presence of forged tickets in circulation. It just left the hooligans to deliver the coup de grâce.

Nobody from UEFA, European football’s governing body, has ever been truly called to account for the tragic events in Brussels, and for their disastrous decision to stage the game at this shambles of a stadium. UEFA has never had the decency to admit to its culpability, to its significant part in what happened. Liverpool’s hooligan fringe kept the authorities out of the spotlight where they really belonged, right alongside them.

Over the years, much of the worst of football violence has occurred outside the stadia, in surrounding streets and town centres. Where crowd trouble has occurred inside football grounds, two factors have routinely been present; inadequate crowd segregation and alcohol. By May 1985, there was every reason to expect that the football authorities and police everywhere had learnt those lessons. Alcohol had long been banned inside grounds and on organised transport to matches, and fans had long come to accept that bars near to grounds would be closed. Indeed, finding a bar or pub open and trading normally near a ground would almost be an insult to a hooligan, as though he had been deemed not worthy of special measures, not dangerous enough, his presence not acknowledged, thus providing every motivation to prove them wrong. A town shuttered and boarded up whilst its residents cower behind locked doors and hold their breath is enough to make any hooligan burst with macho pride. It is possible, even commonplace, for a city to impose a fairly effective, if not cast-iron, alcohol curfew. Rome had certainly got close to it twelve months before Heysel. Of course it is an imposition upon the normal lives of the local population, and of course it isn’t fair. Of course it cannot be justified just because some English can’t control themselves after a few beers. But it can be done.

In Brussels, however, it was harder to find a bar that was closed, even in the vicinity of the Heysel Stadium itself, including one right opposite the main approach to the stadium for Liverpool supporters. We witnessed with rising disbelief (and it must be said, delight) how easy it was to buy beer. For the bars of Brussels it was business as usual, and they did a lot of business that hot sunny day. The carrot was dangled, and taken voraciously. It meant many Liverpool fans arrived in varying stages of intoxication –– that is beyond doubt. But there was another, less obvious effect of the bars remaining open: it sent a signal that today lads, all your usual rigorous match day disciplines and impositions are suspended. This cultural remission made it feel like being on holiday; the end of wartime rationing; a prisoner finding his cell door wide open and nobody about. A tone was set, and an underswell of recklessness, lawlessness and anarchy developed: we don’t have to behave today. Some football supporters don’t need any second invitation, but they got one nonetheless.

If any confirmation was needed that normal rules had been suspended for the day, the casual laissez faire attitude of the police and the flimsy security checks outside and inside the ground provided plenty. In another major departure from convention, few fans were stopped and searched at the turnstiles, or had their tickets checked on the approaches to the stadium. In Paris in 1981, fans had been required to show their tickets at several concentric rings of steel before reaching the stadium. Without a valid match ticket, that was as close as you were ever going to get. At Heysel, although there was no shortage of police and barking dogs and metal barricades, it appeared as though they were there for a separate event entirely; they didn’t intervene in our lives in any way.

A similar absence of familiar basic procedures prevailed at the decrepit, archaic turnstiles. Had there been stewards or police immediately beyond the turnstiles to deter people from either trying to break in without tickets or from using fakes, it would have paid great dividends. Again, that was the custom at home. Instead, a sea of forgeries swept through unchecked and unnoticed, some fans just offered cash or pushed through, and the word spread rapidly that tickets may not be entirely necessary to get in to this match. Our precious tickets that we had sweated to get hold of were relegated to optional extras. Once again, the message seemed to be “do as you please, we have no control, no idea and quite frankly no interest”. Like children given too much freedom and not enough discipline, that freedom was abused by some.

Once inside the shambolic stadium, the ineffective control over ground admission, the apparent lack of expertise in handling a crowd and the magnitude of the occasion led to the inevitable result: utter chaos. More supporters were crammed into Blocks X and Y than there was room for.

By 7pm on match day, all of these factors conspired to leave many thousands of Liverpool supporters shoehorned into a shabby, sweltering, over-crowded terrace under a warm sun, with a collective air of indiscipline and the temporary suspension of usual match day patterns. An industrial quantity of alcohol had fired imaginations, deadened inhibitions and further fuelled the brooding undercurrent. And there, just a few feet away in the adjoining section of terrace beyond some flimsy chicken wire, was Block Z, not empty or neutral but occupied by rival supporters. That football fans will partake liberally if bars are open is one of life’s constants. Their refusal to tolerate rivals in their midst is another. Football supporters are nothing if not territorial, and this was after all our end of the stadium. To some amongst the Liverpool supporters –– those who have ingrained within them that dismal primal instinct for violence –– the Italian proximity was inflammatory and, as the US military might put it, an intolerable violation of their territorial integrity. And Block Z, as yet by no means full, also held the blissful prospect of the extra space that our section so clearly lacked. And what was to stop us laying claim to it? –– a handful of ill-trained police and a flimsy stretch of chicken wire.

Could you ever devise a more volatile cocktail at a football match? There was motive, opportunity, and no apparent deterrent –– the conditions were perfect. In the circumstances, the only surprise would have been a trouble-free evening. And given an identical set of circumstances, there can be little doubt that had any other mass-supported major English club reached that final instead of Liverpool, their fans would have behaved exactly as Liverpool’s did, if not worse. There would still have been confrontation, the ground would still have been a ruin, the wall would still have collapsed, and the same history would have been made.

Proper ticket allocation, good ticket control at the stadium approach and access points, effective crowd segregation inside, adequate policing and security arrangements, appropriate facilities and strictly enforced alcohol bans or restrictions: all these actions would have denied the opportunity for violence. ‘Controlling the controllables’, in business jargon. In failing so transparently in every single one of those basic areas, the authorities handed on a plate to the small thug element amongst Liverpool’s contingent the sort of opportunity which they had properly been denied at home for years, and which in all honesty they never expected to see again. And when they saw it, a depressing handful tucked in like a beggar at a banquet.

And yet, and yet, even then, even at that late stage, after virtually everything that could have been done wrongly had been, the tragedy could still have been averted. All that was needed was for the police, inadequate in numbers and training though they were, to be quicker to recognise the blindingly obvious warning signs and take decisive action to separate the rival sets of fans and defuse the inflammatory, simmering eyeball-to-eyeball proximity, by forming a human barrier between the rival supporters and creating a buffer zone. It was the custom then, in England and almost everywhere else. They could then have maintained the buffer zone throughout the match, with the aid of reinforcements, or had the option of leading the Italian supporters out of Block Z to the other end of the ground where their own supporters were (and where they would have preferred to be anyway), which would also have allowed the Liverpool contingent to overflow into Block Z to ease the congestion. Instead, they became paralysed by indecision as the situation worsened, and when what a Belgian eyewitness in Block Z later described as “the incomprehensible panic of the Italians” took hold, the police merely herded the fleeing Italian fans at baton point back towards the trouble they were seeking to escape. The pressure on the flimsy, crumbly perimeter wall grew and grew, and finally, disastrously, proved too much, leaving the police to watch on helplessly as the results of their indecision swelled to monstrous proportions.

Liverpool in particular, and English football in general, took all the blame and responsibility. In the dock of public opinion, Liverpool’s supporters stood alone, guilty without the need for a trial. But alongside them, shoulder to shoulder, belonged a host of others: the UEFA officials who nominated a venue unfit to host anything more tumultuous than a whelk stall; the Heysel Stadium management who knowingly, willingly and openly sold tickets for the Liverpool end of the ground to Italian supporters; the bar owners who against their better judgment, police advice and all known precedent remained open and serving alcohol throughout the day; the police, who displayed a complete lack of awareness or urgency in the face of blatant warning signs, and incomprehensible inertia when clear decisive action could still have saved the day; and the Juventus supporters who carried inflammatory flags and banners to the match, as well as at least one firearm (a starting pistol, as it turned out, but who was going to know that from a distance?), who destroyed perimeter fencing, fought with police and launched an attack on Liverpool’s supporters from the running track around the pitch, yet somehow emerged with their reputations intact.

Weighed down by collective guilt, Liverpool’s mass of genuine supporters felt utterly let down by the behaviour of the few at Heysel, whose lack of self-control brought appalling consequences for the Italian victims, but also besmirched their own club’s proud name across Europe and brought shame, disrepute and universal vilification to each one of us that we have still not shaken off. For many years it deprived club and supporters of the most exciting, uplifting experience available –– involvement in European football. As individuals we felt as though we had paid the price many times over. Every Liverpool supporter I know and have ever met was sickened that innocent people, fellow football fans there for the same reason as us, died at a football match, and that a small minority of our own fans had a large part to play in it. I don’t know any Liverpool supporter who seeks to deflect responsibility for the actions of some of our supporters that night. But I still believe that the accusation that Liverpool’s supporters killed 39 people that night is narrow and over-simplistic. As I said at the start, I didn’t think the story had been properly told. Heysel is unfinished business.

The deaths at the Heysel were wholly and easily preventable. They were the obscene consequences of gross negligence, stupefying incompetence, criminal lack of forethought and a whole succession of people –– from the decision to use the apology for a stadium to the ticket selling arrangements to the policing –– failing to do their jobs properly.

Had they done so, ugly primitive tribal aggression would have been properly denied its stage, and the chain would have broken.

Tragically, it held.

These are the names of those who went, like us, to watch a football match, and never returned:

Rocco Acerra (29)

Bruno Balli (50)

Alfons Bos

Giancarlo Bruschera (21)

Andrea Casula (11)

Giovanni Casula (44)

Nino Cerrullo (24)

Willy Chielens

Giuseppina Conti (17)

Dirk Daenecky

Dionisio Fabbro (51)

Jaques François

Eugenio Gagliano (35)

Francesco Galli (25)

Giancarlo Gonnelli (20)

Alberto Guarini (21)

Giovacchino Landini (50)

Roberto Lorentini (31)

Barbara Lusci (58)

Franco Martelli (46)

Loris Messore (28)

Gianni Mastrolaco (20)

Sergio Bastino Mazzino (38)

Luciano Rocco Papaluca (38)

Luigi Pidone (31)

Bento Pistolato (50)

Patrick Radcliffe

Domenico Ragazzi (44)

Antonio Ragnanese (29)

Claude Robert

Mario Ronchi (43)

Domenico Russo (28)

Tarcisio Salvi (49)

Gianfranco Sarto (47)

Amedeo Giuseppe Spalaore (55)

Mario Spanu (41)

Tarcisio Venturin (23)

Jean Michel Walla

Claudio Zavaroni (28)