Way back in 2011 – when Andy Carroll was still Liverpool’s Bright Young(ish) Hope – I created ‘TPIC’ – the Transfer Price Index Coefficient; a system I devised to give an idea of the best (and worst) value signings in the Premier League era, based on the TPI project I co-authored with Graeme Riley. (TPIC, for those slow on the uptake, is ‘Transfer Price Index’ with ‘Coefficient’ added.)

I’ve revisited it a couple of times since then, and towards the end of last season thought it was worth seeing what – if anything – has changed in the past few years. I worked with Tableau viz Zen Master Rob Radburn on creating an interactive list, but never quite finished the article, as the season lurched from the tiresome chaos of every dropped Liverpool point to the broad satisfaction of finishing in the top four – at which point, season reviews and transfer chaos.

But I’ve finally finished this piece, which is a free read for the Top 100 value signings across the Premier League era, but with Liverpool’s top 20 and bottom 10 analysed for subscribers only.

Before getting onto the lists I need to briefly explain the process, otherwise it won’t make sense. (Although some people will skip the explanation and get angry at the conclusions anyway.) The top 100 graphic will follow at the end of this article, after the explanations, and also some observations.

First of all, what makes the comparisons possible – in terms of transfer fees – is that everything is in assessed in current-day money. (As an aside, see the top 100 in terms of the most expensive signings here. These are purely fees, no additional analysis. These are the most expensive, good and bad – and at times, terrible.)

At the Transfer Price Index – a project Graeme Riley and I co-created in 2010 – we have tracked every signing since 1992 (the Premier League era seemed the easiest place to start, with what is a side project and not a full-time undertaking), and with each season there is either inflation (mostly) or deflation in the average price of a transfer fee. Those annual index figures can then be used to convert any price into “today’s money”.

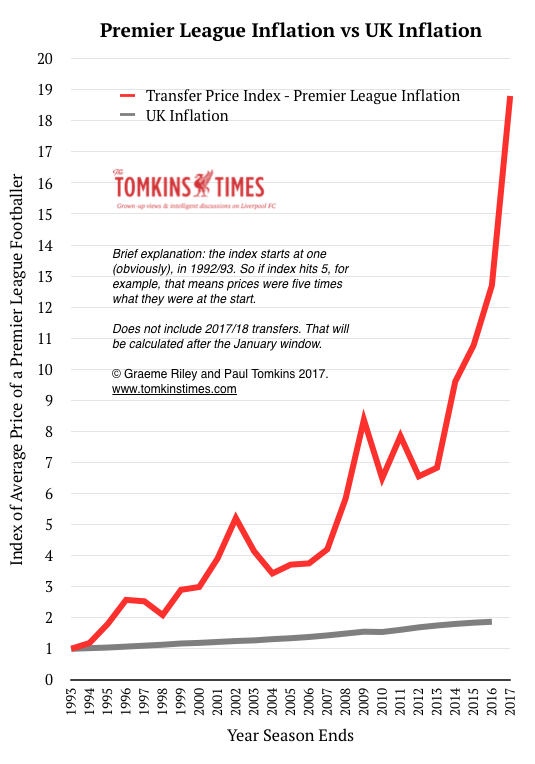

So, 1992/93 starts with the index of 1. Ten years later it was 4.1, meaning that, in a decade, the average price of a Premier League footballer had risen four-fold. Twenty years later, it was 10.7; almost an eleven-fold rise from the original figure. Soon it was thirteen times; and currently it’s eighteen times the original fee. So for every £1m spent on a player in 1992/93, the current equivalent is £18m. (But deflation means that this is not linear; if an expensive player was bought during a period of deflation, this makes him even more expensive in relative terms: just like buying a house for £100,000 when the market for the same kind of property has slumped to £80,000.)

By putting everything into current day money, deals can be assessed as “equals”; after all, you can’t say that £2m was cheap in 1993 (it wasn’t!) just because it’s now cheap in 2017. And now you know that the £2m equates to £36m, whereas with standard inflation it would equal just £4m, which clearly is not expensive but inexpensive (and which shows that football inflation runs far wilder than standard UK inflation; again, see graph above). By converting all deals into current-day money, a way of assessing them could be developed. Hence: TPIC.

As I stated at that time of the original concept, I feel that TPIC is perfect for definitely nailing what is/was a great buy, in terms of value for money; but those it labels as “bad buys” are less accurate, as I will go on to discuss. But even so, it’s still just a model that gives conclusions based on a few factors – it’s not to be taken as gospel.

To be 100% accurate would require a far more detailed assessment of each player, which isn’t really practical with several thousand transfers since 1993. The whole point of the model is to get an idea.

(The database now has over 4,000 entries for players bought by clubs whilst they were in the Premier League, which also excludes nearly 1,000 trainees who have made their debuts since the start of 1993/94; so someone like Steven Gerrard will not appear in the TPIC listings, as he was never “bought”. And some players may be in the database several times, for each time they were bought by a new club. (Note: the data for 1992/93 also includes the hundreds players who were already at clubs at the start of the Premier League era so I excluded that season. Free transfers were also excluded, as value from transfer fee paid is not a factor here – it’s hard to judge the value of something that is free, after all, and here, wages would be more of a factor.)

The idea was to create something fairly objective, to cut through the subjective noise we all offer on any given player. And it’s a method of assessing the deals rather than assessing the players themselves – after all, players can be good at one club and terrible at another. But there is a little bit of subjectivity, in how much I weighted the scoring system.

The system looks at several key factors in any given transfer: the price paid (converted to 2017 money); if applicable, the price later received (again in 2017 money); the number of league games started (as that was the original data we had); the net figure of any profit or loss upon leaving the club; and the mark-up, if there is one, as a percentage.

So a player bought for £100,000 in 2017 money and who moves on for £1,000,000 in 2017 money scores very well in terms of mark-up – ten times! – but the £900,000 doesn’t score too well as a net figure, as it’s still a fairly small profit in terms of the average fees paid. For instance, you can buy a £5m player in 2016 and in 2017, after a year of failure, he could be worth £6m, or £8m, based simply on the fact that prices have risen. (A bit like buying a house, doing no work to it, and selling it a year later when prices have risen.)

The ideal signing would therefore be cheap (better value for money); play a lot of games (showing his worth by years of service); and be sold for a large profit, often when about to ‘melt’ (recouping money on a diminishing asset).

Obviously some excellent signings don’t fit all these criteria, but these seemed the easiest to monitor with the data at hand. So the only transfers listed in the top 100 are clearly successful; whereas I’d say that 80% of the worst transfers are genuinely bad or underwhelming transfers, with around 20% who, though poor value in financial terms compared to the average prices (cost a fortune, but left for free after years at a club), were still successful signings. So I tend to focus on the top 100, as the bottom of the list is too controversial.

More detailed performance data could of course be added, but I saw no easy way to do this without confusing matters; also, as already noted, this is not our full-time undertaking, and so anything that takes too much time is just counterproductive, and will never get finished. Also, only in recent years have performance metrics been worked into “scores” that reward all manner of on-field activities (such as WhoScored’s rating out of ten for each player over the course of a season). So these could not be applied back to 1993; and plenty of people do not agree with those scores anyway.

To use things like goals or assists ignores players whose job doesn’t involve goals or assists. To include clean sheets ignores team organisation or the job done by players outside of the defence. To include trophies won ignores players who were never moving to clubs expected, or destined, to win trophies: all those struggling Premier League clubs whose great success would be to survive into the next season. So I stuck with this basic tenet: if the player started a lot of Premier League games he must be doing something right, whether that’s for Manchester United or Bolton Wanderers. Few poor players play hundreds of games for the same club in England’s top flight, while the best will often involve a transfer fee that can be assessed.

For the purposes of TPIC I only include transfers who have been bought and sold (or who retired). This is because players still at their current clubs have no “sale” value, and are still active. In the past I asked some experts for estimates for sale value for Liverpool’s existing players, for a piece for this site, but it’s too complicated and, again, subjective, to use for all clubs. Also, websites that estimate current market value seem to undervalue by virtue of anchoring the estimates in the past, without taking inflation into account.

With nothing in the “sale fee” column, only a handful of current transfers would be in the top 100 anyway, so excluding them doesn’t alter too much. As an example, if he left for free or retired, Leighton Baines would enter the top 50 for his time at Everton, based purely on appearances made (and the fact that the fee wasn’t too high to start with; the lower the fee, the less there is to “pay off” by playing games). But he’s one of a few exceptions.

Plenty of other current players stand a chance of making the list, but mostly due to sell-on fees. While the list is in 2017 money (which can only be calculated in February 2017 once the window closes), the data was assembled in March, so it doesn’t include players who have moved this summer.

(For the record, Romelu Lukaku’s time at Everton would rank 41st. He wasn’t exactly cheap – £48m after inflation, and he didn’t play hundreds of games for the Toffees. But the maximum Man United could end up paying – £90m – represents a big profit, so it scores very well there, but in terms of mark-up it less than “doubles” their money after inflation is applied. By contrast, John Stones, sold to Manchester City last summer, represents better value from Everton’s point of view, as they received over five times what they paid, and he was also a regular in the team while at Goodison.)

For this version of TPIC I have tweaked the coefficient to additionally reward really high numbers of appearances. Overall, the average number of appearances per player, per transfer, is well under 50. So while every appearance is worth 1 point in TPIC, that rises incrementally when passing 50, 100, 200, 300 and 400 league starts. The idea for this is to make 10-15 years of regular service at a club equitable to selling a player for a record fee. You could argue that playing games is more important than a fee recouped, but a player being sold for a record fee is pretty much definitive proof of his success at the club that are selling him. He may flop upon moving, but to bring a large sum, he has to have been doing well.

For instance, Frank Lampard made 404 league starts for Chelsea, then left for free. So there was no recouping any money at the end of it, because he’d played beyond his saleable age. However, if he’d played 100 games and been sold in 2004 for what now equates to £100m, that has be of equal value in terms of judging him a successful purchase.

Why Is Resale Value So Important?

I think there’s a lot of misunderstanding surrounding buying younger players with potential resale value; as if it can only be a purely business idea, and nothing to do with the football. This is wrong. For many clubs, resale value is vital – although perhaps slightly less so as television money skyrockets. (But of course, they still have to buy players in this inflated market.)

Older players have their advantages (experience, mainly), but are logically nearer the end of their careers, and have had more time to pick up game-altering injuries. They have been in the game longer, so probably expect higher wages. Often clubs are paying for their past glories rather than future production. And players in their late 20s usually come with a fee that is in keeping with someone who is 24 or 25, but unlike them, diminishes almost overnight.

Older players can also arrive already sated by what they’ve achieved and not necessarily have the hunger that a younger equivalent possesses (though some older players remain evergreens, even into their mid-30s; these would be exceptions rather than the rule, and they are often on free transfers, with wages the only expense. And of course, some young players lose their hunger as soon as they make the first team or get a big move).

Younger players come mostly with different risks: Will they fulfil their potential? Will they prove immature? Do they lack experience? But on the whole I believe that they make for better buys, in terms of pound-for-pound spending. This is not to say that you should exclude bringing in older players; just don’t make a habit of it, especially if you’re not bringing through younger players from your academy to counterbalance the average age of the team.

Resale value is the main reason why younger players make for better purchases. It’s preferable to have five great years from a player bought at 20 than five from one bought at 30 – if those two sets of five great years are equal in terms of quality – because the one bought at 20 could be sold at 25 for a ton of money to reinvest in the side (or play for another five-ten years), whereas the one bought at 30 retires at 35, and gets you nothing at the end of it. Providing that a club is not looking to make profits simply to buy extravagant goldfish tanks for the boardroom, the recouped fee can be reinvested in the side. Southampton are a prime example of this – they sell players (if they want out), but reinvest smartly, so that they can have two players instead of one. Last season, they reached a domestic cup final, played in the Europa League and still finished in a respectable league position, which is not easy with so many extra games.

This is obviously hard to sustain for the long term – the Lyon model from a decade ago, as outlined in Soccernomics, eventually ran dry – but would Southampton be any better now if they’d kept everyone they’d sold in the past five years – i.e. after the sale of Gareth Bale and Theo Walcott and time in the second tier – and not brought in the new additions? Some of their best assets only arrived after selling their existing best assets. Had they not sold Dejan Lovren, they may not have bought Virgil van Dijk; without selling Adam Lallana, they might not have bought Sadio Mané. If they sell van Dijk, they could strengthen three positions.

Given Southampton’s stature and budget, any form of sustained success is proof of their methods working. And it has to be recognised that once players want out, keeping them can be counterproductive. Surely it’s better to buy Manolo Gabbiadini aged 25 for £15m and to sell Graziano Pelle, aged 30, for just a fraction less?

Age-Old

The average age of the top 100 TPIC signings is just 22.4 years of age. However, narrow it to the top ten and it then falls by more than two further years, to just 20.3 years of age. Remove the three goalkeepers (who peak later in their careers), and the average age for the remaining seven players is just 19. (N-n-n-nineteen.)

To go back to an earlier analogy, I think of resale value as like buying a house. If you buy young players it’s like buying a house with potential for a lifetime of enjoyment. Your house may not have any value left at the end of your lifetime, but by then you’ll know you’ve had a good life there. Equally, you can sell up halfway through and perhaps get the money to buy an even better house.

However, if you pay a lot of money for a house that is on the edge of a cliff – where the land is eroding into the sea – then you won’t get a lifetime there. You may have a couple of wonderful years, before your house washes into the sea, and with it, you have no money to go and live somewhere else (as you can’t insure against ageing).

Robin van Persie Syndrome

A great season for Man United when bought aged 29, for what is a whopping £64m in today’s money (but even that was cheap due to only having a year left on his Arsenal deal), to be sold for just £5.8m three years later – this could be called Robin van Persie Syndrome.

For United, van Persie all but washed into the sea. However, was it worth it? The league title, as he briefly shone, suggests it was. However, United’s travails since he started to melt (and was sold for peanuts) suggests that had they invested in someone younger they might have rode out the crash that followed Alex Ferguson’s departure and been in a stronger position now. (Instead they had Wayne Rooney also on the wane, no pun intended, in a double-melting/cliff-face dilemma.)

Perhaps Anthony Martial, signed in 2014, was too extreme – as a teenager he was possibly too inexperienced to bridge the immediate step-up in difficulty; or maybe his fee, which at its full add-ons cost is now £83.7m after two years of football-wide inflation, was too heavy a burden, at such a big club (but he still has time on his side, and yes, resale value; were he to move this summer, he could still fetch a pretty decent fee). And of course, had they signed a hot-shot 23-year-old in 2012 there’s no guarantee he’d have done as well, let alone better, than van Persie. But is a short-term boom followed by a bigger bust worth it? Had Alex Ferguson stopped planning long-term, as he moved towards his mid-70s?

What you can say is that a club like United, with a monumental turnover, can take risks that a club like Southampton cannot, even with the increased prosperity of the English top division. Equally, United’s fall from grace post-Ferguson may not be just down to the change in manager.

So anyway, without further ado (and no Freddy Adu), here it is:

The players in the list don’t really need explaining, now that the process has been described. However, it is a mix of world-class players and exceptional clubmen.

The top three are the three players whose sale received the biggest fees, in descending order; Cristiano Ronaldo and Gareth Bale making quite a few appearances after cheapish moves, before the massive profit came along. By contrast, Nicolas Anelka is in for the huge fee and the massive mark-up – an astonishing 39 times what was paid. But five of the next eleven places in the listings are players who left their clubs on a free transfer, or retired, after racking up between 302 and 404 league starts.

However, one interesting thing struck me. With inflation, the buyout clause of Neymar is almost identical to the fee Real Madrid paid for Cristiano Ronaldo. Neymar is now 25, roughly the same age as Ronaldo eight years ago (24), when he moved to Spain. And the fee Real Madrid paid for young French scoring sensation Nicolas Anelka in 1999 isn’t too far below the £160m they are reportedly eager to spend on Kylian Mbappe, another young French scoring sensation. (Anelka scored just two league goals for Madrid.) It is worth noting, however, that our inflation rates are based purely on Premier League purchases, and therefore doesn’t necessarily reflect the different financial powers of clubs like Real Madrid and Barcelona.

Anyway, in the name of curiosity, here are the eight players whose sale fees exceeded £100m in 2017 money, and the clubs who sold them (six went to Spain, but with Man United buying one, Chelsea the other).

1 Ronaldo C, Man Utd, £225,991,870

2 Bale G, Spurs, £162,040,878

3 Anelka N, Arsenal, £141,047,793

4 Ferdinand R, Leeds, £132,902,073

5 Luis Suarez, Liverpool, £127,629,404

6 Overmars M, Arsenal, £117,353,677

7 Torres F, Liverpool, £116,819,474

8 Juninho Paulista, Middlesbrough, £105,478,862

Liverpool FC Analysis

The top 20 Liverpool FC buys, and analysis, follows below for subscribers only. This also includes the worst 10 buys by the club, as well as what Philippe Coutinho would need to be sold for (if he was sold) for him to top the list as the Reds’ best value buy of the Premier League era.

[ttt-subscribe-article]