By Paul Tomkins.

I don’t know what people expected when Jürgen Klopp took over a goal-shy side in October, but I’d argue that asking a manager to inherit a squad of what, to him, were 25 strangers, when 11 games have already passed, and then to totally transform them with no preseason to train them, and no transfer activity to bolster the ranks, is not really familiar with the way the real world of football works.

Add that he faced 52 games in seven months – a quite ludicrous schedule – and as I’ve said before, this season was not so much a marathon but a marathon straight after another marathon, with a few sprints thrown in. Indeed, given that some teams played barely 40 games this season, and Liverpool played 63, it feels more like a triathlon.

What did Klopp achieve? Well, he took over a club and improved its league position from that time by two places, despite a subsequent injury crisis and adding no new players. The overall league form was still nothing to write home about, but Liverpool were mired in mid-table when he pitched up, and injury after injury was about to strike. Hell, Lucas Leiva ending up playing a cup final at centre-back. Players we didn’t even know were still alive, and those we’d never heard of, were suddenly getting games. By mid-May, possibly several hundred players had appeared for the club under the German.

So, aside from improving the league position to something closer to a reversion to the mean – and nothing more – his team also took Manchester City to penalties in a cup final; and lost on what is a fairly random way to conclude a game, with skill only playing a small part (and let’s face it, we’ve seen our club win cups on penalties, whether it was deserved or not). And, in mid-May, his team was within 45 minutes of Champions League football and a European trophy.

The collapse in the second half in Basel was hard to stomach, but I think we’d all have taken two cup finals and being that near to the Champions League back in October, as the lustre had well and truly worn off Brendan Rodgers’ tenure. Remember, this was a period when Liverpool appeared to have no idea how to break down the Carlisle United defence.

Perhaps penalties cost Klopp in both finals, with Sevilla riding their luck. I’ve never seen Liverpool have so many reasonable handball claims in one game, let alone one half, as they did in Basel – even if only one of those was clearly ball to hand (but as if that’s all that matters when referees give them).

On top of that, there was a clear foul on Roberto Firmino a split second after one of the handballs, that perhaps got lost in the appeals. Liverpool weren’t unlucky in the second half, but they were in the first.

The contrast between the offside “goals” scored in the first-half, by Liverpool, and in the second half, by Sevilla, summed up the night. Had Liverpool been 3-0 up at half-time, no one would have complained or called it unfair. Equally, no one can say that the Spaniards didn’t deserve their goals after the interval, even if Alberto Moreno helped gift them a terribly-timed equaliser (although it’s not like he rammed the ball into his own net; he got beaten by a piece of skill, albeit after a rubbish header).

I don’t think you can now say that Klopp has a poor record with substitutions, even if they didn’t work in Basel. Indeed, he has an excellent record with introductions, with so many scoring goals and changing games. But sometimes they’ll work and sometimes they won’t. It didn’t help that two of his best options (Origi and Henderson) weren’t fully fit, but it made sense to have them in the 18.

Loser?

People may say, after he has lost his fifth successive final, that Klopp is not a big-game master; to quote the latest Nivea advert, a loser.

Well, he masterminded knockouts of Manchester United, Borussia Dortmund and Villarreal, and oversaw league victories against Chelsea (away) and Manchester City (home and away), plus a win against Leicester (one of only three defeats – I know, I know; matron, more drugs please), and a 4-0 thrashing of Everton in the derby. Maybe some of these opponents had their problems at the time, but even so, that’s still a fine record.

Arsenal and Spurs failed to beat Klopp’s Liverpool in three fixtures, with his only big-game reverses the late Manchester United Anfield snatch-and-grab – before the turning tide of the Europa games – and the Stoke semi-final at Anfield, which was awkwardly poised after a fine, but narrow, first-leg win.

Indeed, the Stoke and Villarreal semi-finals sum up the difficulties of game management.

There is no doubt that intervals within games, and the gap between two legs, can lead to so much change. Half-time can be a killer. It’s why players fake injuries within games, or waste time – to halt the flow.

My sense is that what hit Villarreal after they won the first leg of the semi-final one-nil is what hit Liverpool are they won the first-half of the final one-nil. Liverpool were also nervy against Stoke in that semi-final after being fancied to win, and with a 1-0 lead to defend, as Stoke, with nothing to lose, went for it; but Liverpool were aggressive against Villarreal with a 1-0 deficit to overturn.

Similarly – and I wrote this on TTT and hit send literally seconds before Sevilla equalised – it’s always harder to come out and play your natural positive game if you’re 1-0 up at half-time than if you’re 1-0 down. I had literally just typed a warning about how half-times can kill momentum when the ball was in the back of the net.

Because it’s all about what you have, and what you can lose. Indeed, the 2005 and 2006 cup final triumphs under Rafa Benítez are both brilliant examples of the momentum within games (which is not the same as the idea that moment exists between games, which is far more complicated). More than any other games – perhaps because by this stage I was writing about the Reds full-time – these summed up how momentum can switch, no matter what managers do; that they matches can take on a life-force of their own.

We can clearly see what being 3-0 ahead did to AC Milan (overconfidence), and West Ham at 2-0 (panic, at suddenly being favourites). Liverpool were overawed in the first half in Istanbul, and overburdened with the pressure of being favourites at Cardiff. Both times these mental states were alleviated by effectively having “lost” during the match, and therefore having nothing to lose.

To the leading team who feels the game is won, and then finds that it isn’t, can see the opposition like a villain apparently killed in a film, who then suddenly gets up. In 2005, Liverpool were like Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction: Milan thought that it was over, the Reds’ hopes drowned, but up they popped, back for more. Indeed, maybe Liverpool were like zombies: you simply couldn’t kill them.

AC Milan collapsed. Go and look at that team-sheet, and that manager. Look at what they’d already won. It was a team of world-class players at their peak – the keeper aside, every one is a legend, with legends on the bench, too – but watch the video and see the fear in their eyes. Nothing Carlo Ancelotti, nor Paulo Maldini, nor Alessandro Nesta, nor Jaap Stam, nor Andrea Pirlo could do would halt the slide, as they went glassy-eyed and numb. Nothing Cafu, Seedorf, Gattuso, Kaka, Crespo and Shevchenko could do could halt the Reds’ momentum. The game was at that point a runaway train.

The only thing that stopped Liverpool – and this isn’t hindsight, but can be seen in the eyes of the Italian team – was Liverpool themselves. Once it went to 3-3 there was a visible “woahhh!”, as if to go for the fourth would be unthinkable. Milan had suddenly lost the Champions League final; or rather, lost the fact that they’d already won it. And suddenly, at 3-3, they could fight back, with nothing to lose. The fear left them; at least until the penalty shootout, when it clearly returned.

It hurts more to lose when you go 1-0 up, so I can only imagine how that felt for Milan that night. (But fuck it, I won’t try too hard.) On Wednesday, losing three second-half goals after being ahead at half-time was almost a reverse Istanbul, but these two teams were more evenly matched, with Sevilla having won the competition on what feels like an annual basis. So it was nowhere near as bad a collapse as Milan managed 11 years ago, and again, look at the names of that side, and the pedigree of the manager, and tell yourself that 45 minutes of wobbling can’t happen to anyone.

If Klopp is a failure, and Louis van Gaal a success if he lands the FA Cup this weekend, then Manchester United are welcome to that type of success. (Two years and what feels like half a billion pounds in the making. Whoopee.)

I think that had Liverpool gone out to Dortmund on away goals – had they got the game back to 3-3 but Lovren missed the pivotal header – then Klopp would not have been seen as failing in Europe. It would have been a valiant effort, and the Reds would have gone out to a better side.

But then beating Villarreal 3-1 on aggregate, and being 1-0 up in the final, seemed to perfectly set the story for one of glory – something I believe was exacerbated by the unreal quality of Sturridge’s goal which, in some weird way, seemed all the more destined to win the game due to its beauty (which is of course irrational, but our emotions during cup finals are never fully rational).

Now Klopp is apparently that German guy who has lost five finals on the bounce; when some highly touted managers have yet to even reach a final.

Remember, Dortmund weren’t regularly making cup finals before Klopp turned up, and of course, nor were Liverpool. As brilliant as 2013/14 was under Brendan Rodgers – a surreal but genuine title challenge, fuelled by Luis Suarez but overseen by the manager – it’s weird that Liverpool made two cup finals in the months before he took over, and two more shortly after he was sacked. But of course, since beating Cardiff at Wembley in 2012 it’s been a case of finishing as runners-up on four occasions. It’s starting to sting, but it’s better than always finishing nowhere.

I don’t think you can say that cup runs definitely improve teams – that this will automatically make Liverpool better next season – but playing lots of extra games under high pressure suggests a greater education, and the chance for better bonding (just look at the way Sakho and Lovren reacted together at the end of the Dortmund game). The problem, in the short term, is that it’s tough on the players, physically and mentally.

What I can say is that, on average, long cup runs harm league form in that particular season. People are recalling the Reds in 2013/14, and Leicester this year, as examples of why next season could be better for Liverpool, and certainly smaller squads struggle with too many cup games.

Playing fewer cup games won’t in itself make Liverpool successful – it didn’t make Aston Villa much good this year, did it? – but it is one less obstacle for league success with far less travelling, and far more preparation time. You can’t just throw 25 extra games into a season and expect the players to be as fresh as daisies three or four days after each; or for points not to be dropped due to the inevitable mass rotation when competitions collide.

Generally I think the Europa League is not a risk worth taking – that is, until you find yourself doing well, and with the chance of silverware and Champions League qualification. Then it’s worth taking very seriously.

To judge Liverpool’s season, you need to understand what cup runs do to league form (and this is without referring to Everton, Watford and Crystal Palace, and how their league campaigns tailed off once on promising FA Cup runs – and that was with barely a handful of games to contend with; showing that it can just be case of struggling to focus).

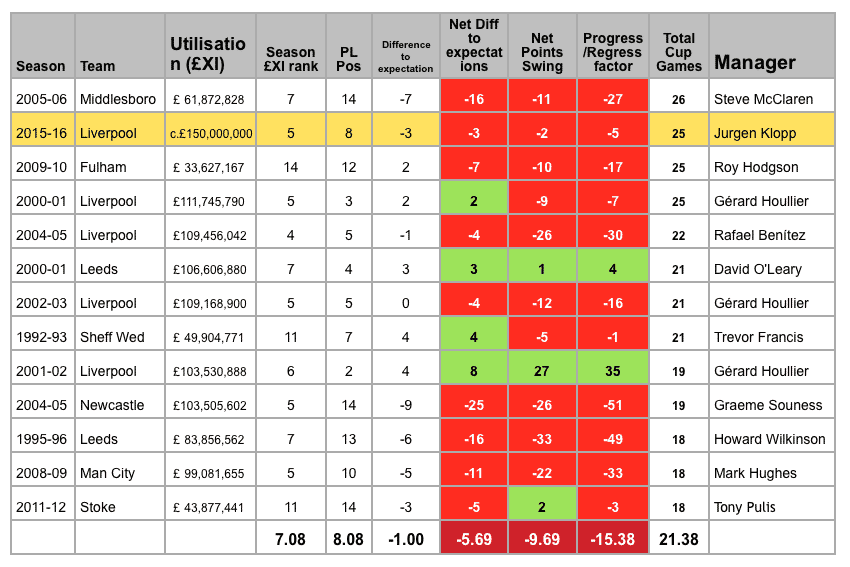

I conducted a study last year, that can be read here. It showed that, on average, one league place and a couple of league points are dropped in years with a lot of cup football – that all Premier League teams across all Premier League seasons; but that the drop is greater for the non-“über-squads”.

Excluding the über-squads (those ranked in the top three for squad or £XI cost), the only clear case of improvement I could find in the study – looking at 18 or more cup games in a season – was Liverpool in 2001/02, where 19 cup games were played; but of course, 25 were played the season before, so this was actually a decrease in demands. (Leeds in 2000/01 are the only other exception, albeit in a very marginal manner.)

The following table looks at cup games played, and the impact on league points (compared against the previous season and the subsequent season, if applicable), and also against the £XI ranking, which is usually very accurate in predicting league position (Leicester fucked that up, but then they fucked up every model, as well as every traditional pundit’s gut feelings). I’ve combined both in a third column.

As you can see, there’s a lot more negative impact than positive, with a net points swing of almost -10, or approximately five points each season. In other words, that would put Liverpool 6th, unless teams above them had also played that many games (they haven’t; Man United will end up playing 21, four fewer than Liverpool, but with a much bigger squad).

As an aside, Rafa Benítez’s Chelsea played the most cup games in the Premier League era, with 27, and in league terms improved on the season before; but that was a double-cup winning season, with the Champions League won, which in itself was therefore subject to cup strain. But Chelsea can be said to have had an über-squad. Liverpool cannot be said to have an über-squad right now, ranking 5th in terms of overall cost and utilisation.

Part Two: “I’ve Seen the Future, And It Will Be; I’ve seen the future and it works”

(© Dearly departed little purple man)

As I said earlier in the season, it was easier for teams to have a handle on Jürgen Klopp’s approach as it was so famous. He arrived with his own well-known style. But did he and his staff have a handle on the other 19 teams?

He would have had a good idea about Arsenal and Manchester City, from the Champions League. He’d have had a good idea about Louis van Gaal from their duels in Germany. But Leicester? Watford? West Ham? And, heaven forbid, Pulis and Allardyce?

Next season the opposition will still know how Klopp plays; but he will know much more about how they play. That has to be an advantage. After all, I think it’s fair to say that Klopp generally did better against teams the more he faced them, although sometimes he was fielding a scratch XI.

I think Liverpool could add 10-15 points next season simply by adding some height. Rafa Benítez did this in 2005; and adding more physical presence, along with other factors, added 24 points to his second season (although obviously you want quality and not just totems).

I keep drawing comparisons, but Klopp is the first Liverpool manager since Benítez that I’ve “got”; though different in temperament, both arrived with a high-pressing reputation, and were tooled-up with two league titles in big leagues (plus some cups), all achieved with outsiders, and then duly took Liverpool to a League Cup final within months of arriving, and a European one a few months later. Liverpool got ‘lucky’ in 2005 in a way that they didn’t in 2016 (although were unlucky in 2007, when they were the better side, and very unlucky in the league 2009, for various reasons, including timing, and Howard Webb – but that’s another story).

I obviously didn’t get Roy Hodgson at all, and he didn’t get the club or its fans. That was a marriage made in hell.

Obviously I got Kenny Dalglish on all kinds of levels, but I never quite got his football 20 years on, which didn’t feel the same as the heady days of 1987/88, but perhaps never could. I still wouldn’t have sacked him (and again, two cup finals harmed the league form), but it didn’t feel like it was going to click in the way that it does right now. Crucially, Kenny – with the help of Damien Comolli – had also spent money, and had longer in the job; indeed, he knew the club inside out before even returning. It was therefore a confusing time, and not one I fully got, even if his replacing Hodgson was almost like a trophy in itself.

I clearly struggled with Brendan Rodgers. I didn’t know a lot about him in 2012, but warmed to the press reports appearing that summer. I grew to like him, but never fully got him; perhaps because his talk didn’t always match his walk, as it were – but also because the teams he sent out over a 3.3-year period were so different. It felt like he was still struggling for his own identity, his own style of play. And he never had the record of success to alleviate the doubts.

That said, after some of my own doubts up until halfway through his first season, and occasionally after, I backed him until earlier in this campaign, when it just looked like the wheels that came off in 2014/15 were not being reinstated, but rather, rolling away down the hillside. As of earlier this season, I really didn’t get Brendan Rodgers.

But I feel I get Jürgen Klopp. Maybe it’s just a case of skewed perceptions – I don’t know. But I feel I understand what he’s trying to do, even if I don’t always understand what he’s trying to say (but it’s usually great fun all the same).

I think that players believe in him, and big names want to play for him. I believe that he has a strong vision, and that he won’t chop and change his ideals to be popular or look clever. It may not work out as we all hope, but I sense he’ll give everything – and demand everything from his players. (Anyone who tries to score an own goal in training will be launched from Melwood to Knotty Ash.)

So the improvement from 2005 to 2006 can be possible again, with the right kind of additions, and the right kind of training. And remember, although Liverpool had just won the Champions League in 2005, none of the signings that summer were megastars or household names. They were simply the right pieces.

Pepe Reina was clearly top-quality – even if his first Spanish cap only came months after he was signed by Benítez – but Momo Sissoko and Peter Crouch were pragmatic purchases, there to fill gaps in the squad – to add height, basically, and in Sissoko’s case, terrifying energy.

(Weirdly coincidental, in 2004/05 Benítez tried out three goalkeepers, then went back to his homeland for an uncapped, 6’2”, 22-year old compatriot who played international youth football from U16, U17, U18, all the way through to U21-level. Oh for Loris Karius to be anywhere near as good as Pepe Reina…)

As in 2004/05, Liverpool lost so many points this season due to set-pieces. Back then it was a combination of getting to grips with zonal marking – achieved wonderfully in the next season, but only after a bumpy start – and not having the tallest of sides, bar Sami Hyypia.

In this season’s case, having two short full-backs (with no alternatives of sufficient quality and/or fitness) and often one short centre-half – plus only two tallish midfielders in the entire squad – it meant that there was never much protection on crosses (the full-back on the far post was often out-jumped, and there was no Matic-type to drop into the defensive line), and just a general lack of height on set-pieces.

The procurement of Joel Matip and Marko Grujic shows that this is clearly being addressed (note: this doesn’t mean Liverpool should only sign tall players), but one of the current full-backs has to be replaced, and Alberto Moreno would be most people’s choice. Some of the criticism has been excessive, even vicious, but his flaws appear just too glaring.

Liverpool’s full-backs are a real conundrum: Moreno is super-quick and full of energy, and is good, if not amazing, going forward; but he’s small, rash in the challenge, and switches off. (Some of the criticism of his positioning when he’s upfield is unjust; in the mid-‘90s I played semi-professionally as a striker, but ended up with a stint at wing-back due to my pace. I’d get get bollocked to get forward, then as soon as I got forward I’d get bollocked to get back. And let’s not ignore that Moreno is essentially a wing-back in what’s asked of him.)

Clyne is almost as quick as Moreno, is as strong as an ox, and rarely gets beaten defensively unless it’s in the air, but doesn’t make the most of the space he’s given to attack into, perhaps because teams know he’s mediocre on the ball – flat-footed crosses that rarely cause trouble, and not many worthy shots at goal. If you could take the best of each you’d have the perfect modern full-back, if he’d still a shade short at Clyne’s 5”9”. Still, Clyne seems worth keeping in the XI.

Pace is another area of concern, and perhaps a reason why both of the aforementioned full-backs have been so important this season, despite their faults. Frankly, they are two of the only quick first-team players.

None of Coutinho, Firmino and Lallana can effectively run in behind, nor leave players for dead; they can bamboozle them with skill, and work half a yard, but they can’t do what Eden Hazard did in 2014/15 (and again, at Anfield, the annoying tosser), and not be caught. The interplay between Coutinho, Lallana and Firmino has to be intricate and inch-perfect, as they can’t just chase balls into space, in the way that Origi can, and in the way that Jamie Vardy helped to win the league (I know, I know. Nurse, more morphine!). Often it has been inch-perfect, but it wasn’t in Basel. The option of a quick ball over the top or in behind has to be in the XI somewhere.

And Daniel Sturridge’s injuries have clearly taken a toll, perhaps permanently – but we’ll have to wait and see; the way he was easily done for pace in the second half was painful to watch. He used to absolutely glide across the turf – not a long-stride sprinter like Thierry Henry, but with the same ease of movement.

He remains a world-class finisher, but he won’t terrify defences if he can’t run in behind. He effectively becomes like Robbie Fowler circa 2001/02: a great asset, but an awkward problem too, in terms of fitting into the system and offering every kind of threat. Back then, Houllier preferred Emile Heskey and Michael Owen, and although Fowler had my eternal football love, it seemed a better pairing – at least until Heskey grew less effective (by which point Fowler had been sold).

Contrast Sturridge with the way Kevin Gameiro played on the last shoulder of the Reds’ centre-backs, and scared them silly; in the way that Harry Kane and Jamie Vardy did all season for Spurs and Leicester respectively.

Gameiro, Kane and Vardy are all inferior “footballers” to Sturridge. But they are all better physically, and can unsettle entire defences with their running.

Alan Hansen always said that centre-backs hate to play against pace more than anything else. Klopp’s problem is that, as a spearhead forward in the lone-striker system he prefers, the new half-paced Sturridge isn’t an ideal fit – but of course, Sturridge is always going to be in any manager’s thoughts, given his goal return. As I noted earlier in the season, Klopp’s Dortmund were big, strong and fast; the squad he inherited is not in that mould.

Divock Origi isn’t as good as Sturridge yet, but he panics defenders. Liverpool’s front four in the final all like to play in front of teams; only Origi, on the bench due to injury, ever goes behind them, and he wasn’t fully fit. When he came on against Sevilla it was out wide and couldn’t get into the game. It was too risky to take Sturridge off, but the change didn’t work on the night. Sturridge has the skill and vision to drop deep and play behind Origi, but then he’s in Coutinho’s space.

It’s a conundrum Klopp will have to solve, but as he might say, it’s not so bad having two top strikers. And it’s not so bad having Coutinho, Firmino and Lallana to choose from.

But in order to take the team to the next level, some changes may be essential – although let’s not forget the improvements that can be made on the training ground, and let’s not forget how a team that spends more time together, and whose players mature, can also improve.

Still, my hunch would be to replace Lallana in the XI with a quicker, more direct attacking midfielder, who has more end product – no change in my assessment there. However, Lallana has certainly done enough to now feel like an important squad player, who presses hard and chips in with at least (at last) some goals and assists. I just think that, ideally, the front four probably needs to include only two of those who started against Sevilla, with the other two on the bench.

Adding Origi and, say, Mario Götze to the equation would massively liven things up, and then you could have Sturridge slightly deeper, or pick Coutinho and Firmino instead, with Lallana joining Sturridge on the bench. At the very least it would provide a lot of options.

Of course, Danny Ings may also be an answer. It’s been so long since I’ve seen him at full fitness that I can’t recall if his pace is electric or not, but he’s certainly in the Klopp mould of busy attackers who are, at the very least, sprightly. I think there’s more to come from him. He’s one of the rare players who caught my eye in the lower divisions where I thought “he has it”, aged 20.

One thing Klopp certainly improved this season, albeit over a period of many months, was the fitness of players, and Ings may benefit – especially with two of the Bayern Munich experts moving to Merseyside, as part of Klopp raising the standards. (That said, I’m working on the assumption – based on empirical evidence – that elite clubs employ elite professionals, and that it’s therefore good news when you poach them. This doesn’t mean smaller clubs only employ duffers, of course.)

I’ve noted before that after Liverpool bought players from Southampton – where they’d been trained in the high-fitness, high-pressing style of Mauricio Pochettino – they didn’t get the same “players”. (Why is more not made of this? Players are what they are in any given environment, and change when they are moved to a different one.)

The Southampton trio were entered into the lower-intensity (greater ball-work) training of Brendan Rodgers, and suddenly Lallana, Lovren and Lambert all looked sluggish. Ings is another who arrived from a famously hard-working manager (it was Burnley’s main quality during Ings’ time there), and could look even better than we saw early season.

Sheyi Ojo has genuine pace, and the skill and composure to match – so I think he’ll be in the reckoning more next season, albeit if, at that age (he turns 19 this summer), a dip in form almost always happens. Jordan Ibe’s dip has turned into pretty much a full season, but he was the only senior winger Klopp inherited, and one of only two senior players, full-backs aside, with searing pace.

I personally wouldn’t give up on Ibe, but equally, he’s fallen down the pecking order on merit. Ojo is already a more rounded player – he has that vision and game intelligence, and a mature weight of pass. I think Ojo is a future superstar (barring injuries and ego), but it would be asking a lot at 19 to become a major player at a club like Liverpool; it could happen, but it’s expecting too much.

Lazar Markovic is another whose pace seemed diminished under Brendan Rodgers – I remember thinking “this guy was quick” before he arrived, and not looking it in a red shirt.

While I always think of pace as a constant (you either have it or you don’t; and that you can lose it, but never gain it), I’ve come to realise that maybe 10-20% can depend on fitness (obviously this can be greater when talking about someone returning from long-term injury, who may only be at half-speed, but my point is between “fit” – such as some managers get players – and “super-fit”, as trained by the über-pressers).

I’m not sure Markovic has quite got what it takes mentally to succeed in England, but he wasn’t given what he would see as a fair chance last season, with his brief run of games as a wing-back. I’d like to see him under Klopp, but if it was a choice between him or Götze, the latter wins hands down, not least because of his relationship with the manager, as well as his superior goals record and experience of higher-pressure games.

With Ojo emerging, to add Götze, Ings and Markovic to the squad Klopp had to work with this season, and to keep Lallana, Coutinho, Firmino and Ibe, would mean an excess of vaguely similar types (all under 6ft, all not quite out-and-out attacking talents, and all pretty much able to play wide).

But a lot depends on what happens in the transfer market (now that Liverpool have no European football to offer), and what happens at the Euros, with so many players there; and indeed, if the Brazilians go to the Copa América Centenario.

Dejan Lovren isn’t going to France, so that’s one player who’ll be rested; another is the banned Mamadou Sakho, who could be available again by October if he gets six months, but he might not be able to play football again until 2018, if things don’t go his way.

The prodigious Joe Gomez – big, talented, quick – should hopefully be fit for preseason training, as will Danny Ings. Jon Flannagan now has a chance for a good preseason. And Jordan Henderson and Daniel Sturridge won’t be exhausted come August after missing huge chunks of 2015/16. (Emre Can and Nathaniel Clyne, who missed so few games, are more concerning.) So it’s more a question of sharpness after the delayed preseason, following the summer tournament.

But anyway, there’s plenty of time to look ahead. Before then, TTT will be running separate pieces on each of the players from this season, written by site stalwarts such as Dan Kennett, Andrew Beasley, Simon Steers, Daniel Rhodes and Chris Rowland – plus, of course, yours truly – as well as some debuts from the community’s best commenters. Most of these will be for subscribers only.