By Paul Tomkins.

Based on the evidence of the past hundred-and-two days I haven’t shifted from my opinion that Jürgen Klopp inherited the core of a talented young squad that could, in time, go places; nor that it was imbalanced in a number of ways, and that it would only go places once those imbalances were addressed.

The main problem, which I’d put mostly down to Brendan Rodgers’ preferences in the transfer market (I retain the belief that he’s a good coach, but a poor judge of player), is the make-up of a squad that lacks pace, and more importantly, height. Since Klopp took over there seems to be a huge correlation between goals conceded and the height of Liverpool’s team, as you will see. A ‘big’ problem is that the one fit tall striker, Christian Benteke, is just not suited to Klopp’s style. The absence of Daniel Sturridge means the Reds don’t have that cutting edge.

While Liverpool could obviously use a few better players, the physical shortcomings of the senior squad is what has alarmed me. Liverpool largely outplayed Manchester United today, but were undone by the tallest player on the pitch, and, at the other end, a world-class goalkeeper.

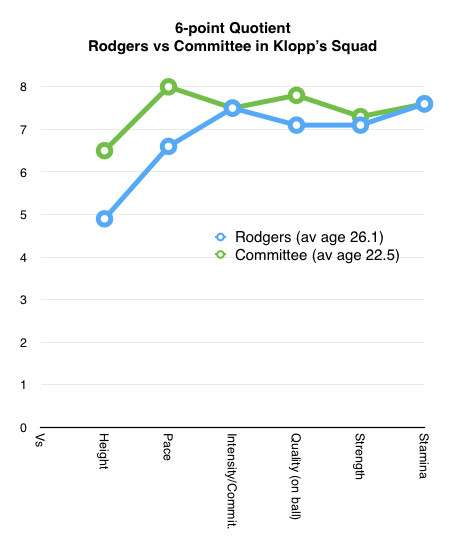

I addressed many of these physical issues two weeks ago, with the Height/Pace/Intensity/Quality/Strength/Stamina Quotient, and since then Liverpool have moved to overturn those weaknesses in the transfer market. It seems to me that Klopp is well aware of the shortcomings, in a literal sense.

Klopp inherited problems that he cannot be expected to have solved within three months. The glaring holes in the squad, exacerbated by injuries, were totally beyond his control. (Even if his training methods and/or playing style may have contributed to some of the injuries; it’s hard to say, although the insanely hectic schedule in itself suggested injuries would occur. And he cannot be taken to task if the players weren’t fit enough when he arrived.) He has had to recall several youngsters from loan this January, including a goalkeeper (Danny Ward), just to get a closer look at his options.

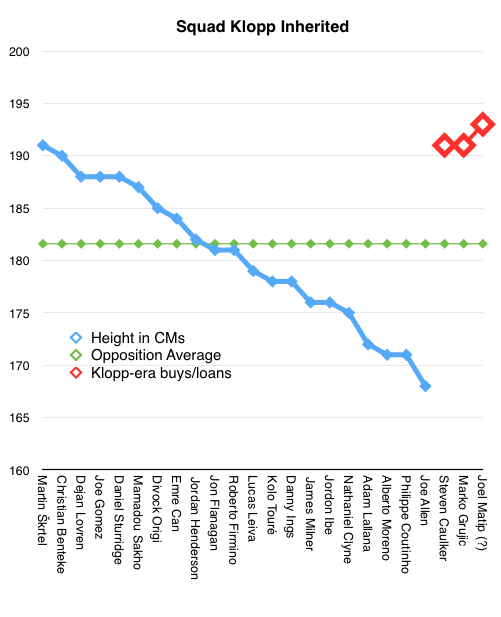

The new signings seem to fit my argument: one is only a short-term loan, while the other two (one confirmed, another – Joel Matip – heavily touted as being a pre-contract agreement) are for the summer at the earliest.

You can improve players technically and tactically, and you can improve fitness – even if these take time. But you cannot alter a player’s pace (by more than a tiny degree in relation to fitness/sprint training) and you certainly cannot alter height, short of the shin-bone extension surgery Jude Law goes through in Gattaca. You can make them a bit stronger but it’s hard to totally transform a player through gym work, and again, it takes time to make improvements. Some younger players will fill out and bulk up between 20 and 22, but I imagine that it can become a trade-off between strength and speed/agility/quickness off the mark.

Look at the height of the Liverpool squad Klopp inherited, versus the league average (based on all of the starting XIs Klopp’s Reds have faced). Now look at the three new signings/proposed signings: three giants. Two are centre-backs, although interestingly, the other is a midfielder.

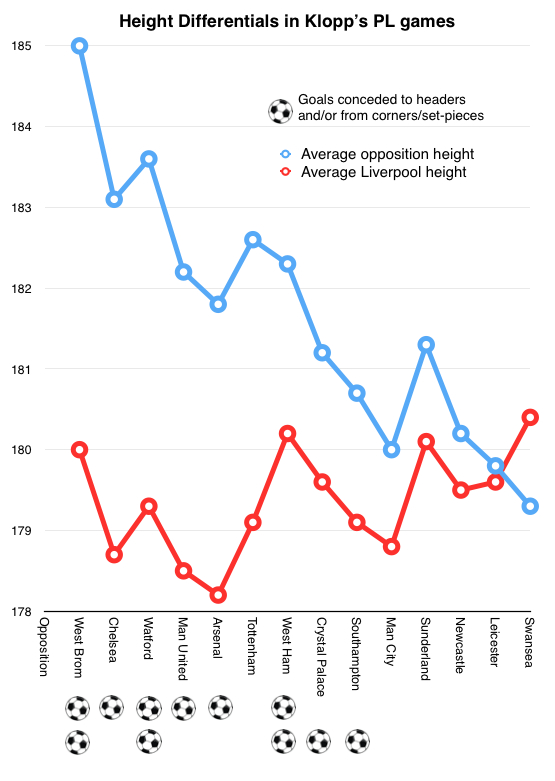

If that doesn’t seem like rocket science, the next graphic will show just how much being significantly shorter than the opposition has cost Liverpool. The greater the gulf in size, the greater the likelihood that the opposition will score a headed goal against Liverpool (or score from a corner, via bad goalkeeping).

England is a league where height counts. Yet Klopp inherited a diminutive squad. In 13 of the 14 league games Liverpool have played under Klopp the Reds have been the smaller side. The only exception, by a narrow margin, was Swansea.

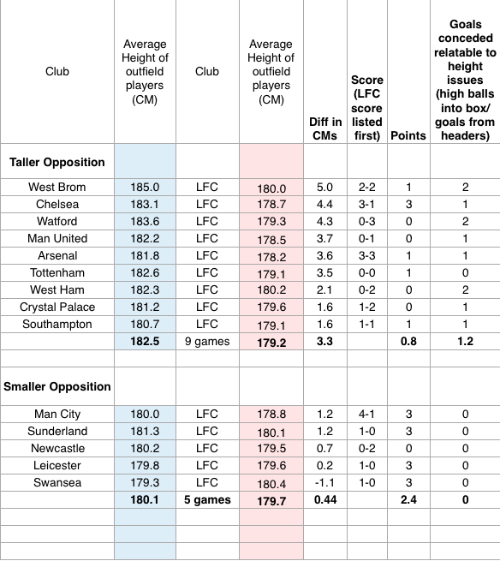

In the five games where there hasn’t been a great height difference the Reds have won four. (These are the four games where Liverpool were the shorter team by 1.2cms or less, plus the one game when they were 0.44cm taller.) No goals were conceded to corners or headers. Klopp’s side average 2.4 points in these five games.

In the nine games where the average height deficiency has been between more pronounced – between 1.6cm and 5.0cm (a massive difference of two inches) – Liverpool have averaged a measly 0.8 points per game, and have conceded an average of 1.2 goals per game to headers and/or from corners. In virtually every game someone has lost out in the air to someone who is at least a couple of inches taller.

These are small samples, but my hunch, as outlined on the pre-match thread on TTT just before the Arsenal game, was that Liverpool would likely concede from corners or crosses as Arsenal (yes, Arsenal) were on average 3.6cms taller – almost 1.5 inches (I’m trying to flit between metric and imperial, as not everyone understands both). I felt the same against United, with Fellaini clearly taller than any Liverpool player.

Is that all just a coincidence?

The problem is that the players most suited to Klopp’s style – and let’s remember, his options are limited by injuries – are mostly small, and mostly of Rodgers’ preference (Clyne, Milner, Toure*, Lallana, Allen; the committee providing Coutinho and Moreno, whilst Ibe was bought as a kid under Kenny Dalglish).

(*Small for a centre-back.)

You can argue that small players can still win headers. Well, they can. But on average they will have very poor success rates in aerial duels, as I will come onto, because they always start at a disadvantage. But it’s not just about those players being small; it’s that most of them lack in other areas.

Those Six Qualities

You can transform fitness, but it is said by those within the game that most of the important work happens in preseason. Once games start coming thick and fast – and no team in Europe has played more times than Liverpool since Klopp arrived – it’s hard to work on fitness beyond recovering and going again.

Prior to the Arsenal game I asked a panel of 25 TTT subscribers, including Dan Kennett, Graeme Riley and Daniel Rhodes, to rate the Liverpool squad in terms of the six key attributes that I outlined a fortnight ago.

The 25-person TTT panel rated Rodgers’ buys that were within Klopp’s squad as having similar strength, stamina and commitment to the committee’s buys, but were, on average, significantly smaller, slower and had less quality on the ball.

The best teams are quick, strong, skilful and usually big. They have all of these qualities, to varying degrees; but rarely have a marked deficiency in any department. Barcelona are probably the exception to the rule, with their tiny playmakers, but they had exceptional players and La Liga doesn’t place as much emphasis on physicality. If you are the best in the world at passing (half the Barcelona team), dribbling (Lionel Messi and others) and goalscoring (Messi again), then you can compensate for a lack of height.

But this is England, where Liverpool don’t have a monopoly on such talent, and where you play teams like Watford and West Brom (the “Stoke Citys” of the previous decade, and Wimbledon before that). This is not to say that these are purely Route One teams, but if you get into a physical confrontation with a load of bigger men, and you are merely a bunch of little men, you’ll probably lose. (Someone on TTT pointed out the boxing adage that “a good big ‘un will usually beat a good little ‘un.”)

(Interactive Tableau graphic created by Robert Radburn.)

Height, in particular, has been a serious problem to Liverpool this season, as further evidence in this piece will show.

Deficiencies

Some smaller players are good in the air. But only if they get a good leap. Defenders often have to wait longer before starting their jump – a striker can gamble and jump early, and if he misses the ball it’s no big deal, because he knows that if just once in three attempts he gambles right he can easily get a goal.

However, if a defender jumps early it’s the same as diving into a tackle – he can present a golden opportunity by guessing wrong and taking himself out of play. This is one of the reasons why, on average, top teams have centre-backs aged over 25. Through years of trial and error they come to know when to anticipate and intervene, and when to hold off.

Also, with set-pieces, someone attacking the goal can run 15 yards and leap; whereas when marking a set-piece you don’t see defenders starting 10 yards behind the goal in order to charge out and get some running momentum.

It’s even harder to get momentum in the jump with zonal marking, of course, as every lazy ex-pundit will tell you without the flip-side: zonal marking wards against the totally free header (full man-marking can result in block-offs and lost runs that can leave a key section of the 18-yard box unmanned). Aside from the three or four players who man-mark near the penalty spot (whatever the system there is usually some man-marking here) there is less scope to get a running jump. So it seems logical that merely being a good jumper is often more helpful attacking set-pieces (or crosses) than defending them.

Being a diminutive side means you can be rendered nervous simply by conceding set-pieces; you can look at the opposition and panic if they tower over you. Add a goalkeeper whose strength is shot-stopping and whose weakness is command of the area (and “presence”), and that sense of panic is amplified.

Liverpool started the game in midweek with no-one over 6’2″ (188cm); Arsenal had players who were 6’4″ and 6’6″. Arsenal scored from a corner, albeit a low one, and the first goal came when Giroud beat Sakho in the air (injuring both men, and ultimately creating the space that Ramsey ran into). Marouane Fellaini is almost 6’5”, and out-jumped four or five Liverpool defenders – but only marginally. Those extra inches made the difference, even though Liverpool had generally dealt with him quite well up until that one crucial moment.

Arsenal aren’t even a physical side, but they’ve added height in recent years. And as Andrew Beasley noted on here, they had just six crosses (less than a third of their usual amount) and yet created three chances from them. United aren’t especially a physical side either, but they are much stronger in the air than Liverpool.

Klopp’s problem is that Liverpool are more fluid without Benteke, so to bolster the side with his height means a massive compromise on movement and pressing; a trade-off that is hard to justify. And yet another trade-off is that Benteke has just one fewer league goal than Lallana, Firmino and Coutinho combined. Benteke is a good player, but sticks out like a sore thumb when it comes to movement and pressing.

You cannot be successful with such compromises. Either Benteke improves his movement (possible, but only within limits) or the others start scoring more goals.

Small and Mediocre

My issue has been not just with the smallness of Liverpool’s players but also the fact that, Coutinho and perhaps Moreno aside, none is an exceptional footballer; and even Moreno is flawed defensively (but his role, in 80% of games, is likely to be that of a quasi-winger; he is the top chance-creating full-back in the Premier League, according to Andrew Beasley).

Most of the smaller players have certain admirable attributes, but the problem arises when too many are in the side at once; their size, and in some cases their lack of pace, leaves too much for which the others must compensate. The problem is that the alternatives, some of whom are taller, are no better.

Clyne is good enough defensively (on the deck, at least) and makes lung-busting runs forward, but just about qualifies as good enough overall, despite his poor end-product on those overlaps. I like Clyne a lot, for his pace, strength and work ethic, but he’s terrible in the air, and mediocre on the ball.

The problem then becomes having two small full-backs at the same time, which means tall strikers (and midfielders) can pull onto Liverpool’s left-back or right-back (which Fellaini did on Clyne), meaning the tactic isn’t limited to one flank. You can limit the number of crosses and long-diagonals, but it’s impossible to totally eliminate them. And it’s hard to avoid giving away corners.

Those two full-backs, plus Coutinho, in the XI and you’re at three small players – probably the limit to carry unless you can play like Barcelona and play against non-English sides.

Then add any one or two of Milner, Lallana, Lucas, Allen and Toure and you are overloaded. Add three or four and you’re likely to seriously struggle (I was going to say fucked, but I’m trying to be polite). Liverpool have been going into games with six or seven players below the average height of a Premier League footballer, and below the average rate of success in aerial duels.

Milner excels at work-rate – he is the league’s elite runner. He has weaknesses that don’t necessarily help, but he can partially mitigate for being only 5’9″ with phenomenal running and a few goals and assists. But is he good enough overall?

Ibe is one of the league’s best dribblers (3rd, based on take-ons this season), but is still learning the game and, in time, should develop into a fine winger.

Lallana presses hard but this season has had zero end-product: lovely turns, but in the league, just two clear-cut chances created for team-mates and zero goals. This is not good enough. He is symptomatic of the hard-work that Liverpool require, but where the sufficient level of quality is not quite there.

All of these players would be better if their weaknesses were being redressed by others, but they’re not. It’s the same with Moreno and Clyne – either is fine; together there are problems.

Terrible Aerial Ability

While I noted that Nathaniel Clyne is good defensively, he’s actually very poor in the air. Indeed, over the past season and a half he’s won a lower percentage of aerial duels (based on Opta data) than Alberto Moreno, who is also poor in the air.

While the data can’t tell us how difficult each aerial challenge was, it backs up the theory, and the eye-test, that Liverpool aren’t very good in the air – mainly because, being short, they are at a big disadvantage.

For the most part, players are achieving fairly consistent figures when compared across last season and this, even if they’ve moved club, like Clyne; which suggests the data is fairly reliable, with only the occasional wild swings in aerial fortunes from season to season to raise alarms.

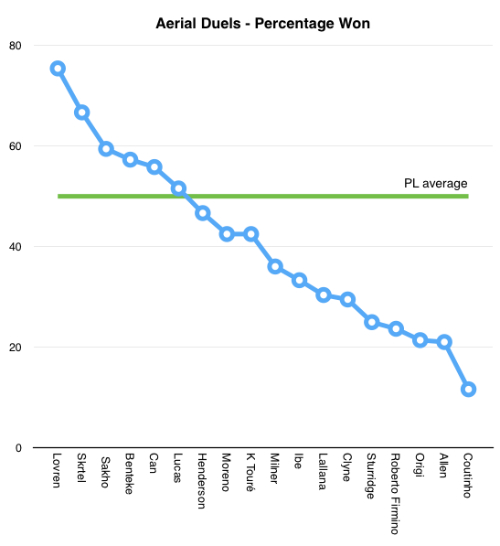

Clyne won roughly one in every three headers at Southampton last season – poor stuff. But he’s down to worse than one in every four this season. He ranks almost as poorly as Joe Allen, Liverpool’s smallest player. This pair are down near the bottom of the lists of between 300-400 players ranked in 2014/15 and 2015/16.

Most defenders should be above 60% when it comes to winning aerial duels. And the top centre-backs are up pushing up towards the 80% mark. Dejan Lovren ranks 6th this season (79%) and 17th last season (73%). According to these figures, Skrtel is about average in the air for a centre-back; roughly 66% won, this season and last, which puts him just inside the top 50. Sakho is worse, at an average of c.60% over the past 18 months (although was generally immense against United).

Weirdly, Glen Johnson ranked 6th out of 381 players in the Premier League last season; 77% of his 40 aerial duels won. Then again, he’s 6’0”, and a former centre-back. He’s down to a success rate of just over 50% at Stoke, but contrast even this poorer figure with Liverpool’s current full-backs, who aren’t even winning 33% of their aerial battles. Indeed, perhaps Brendan Rodgers foresaw a problem by playing Joe Gomez at full-back; he won 50% of his aerial duels before he lost his place, and then injury struck.

Possibly the worst player in the whole league in the air is Philippe Coutinho. But that’s hardly a reason to drop him, as he’s a creative lynchpin (even if his output is questionable for such a talented player). Still, Coutinho is definitely a player who won’t help you one bit when it comes to defending set-pieces. He has attempted 59 aerial challenges since the start of last season and won just seven.

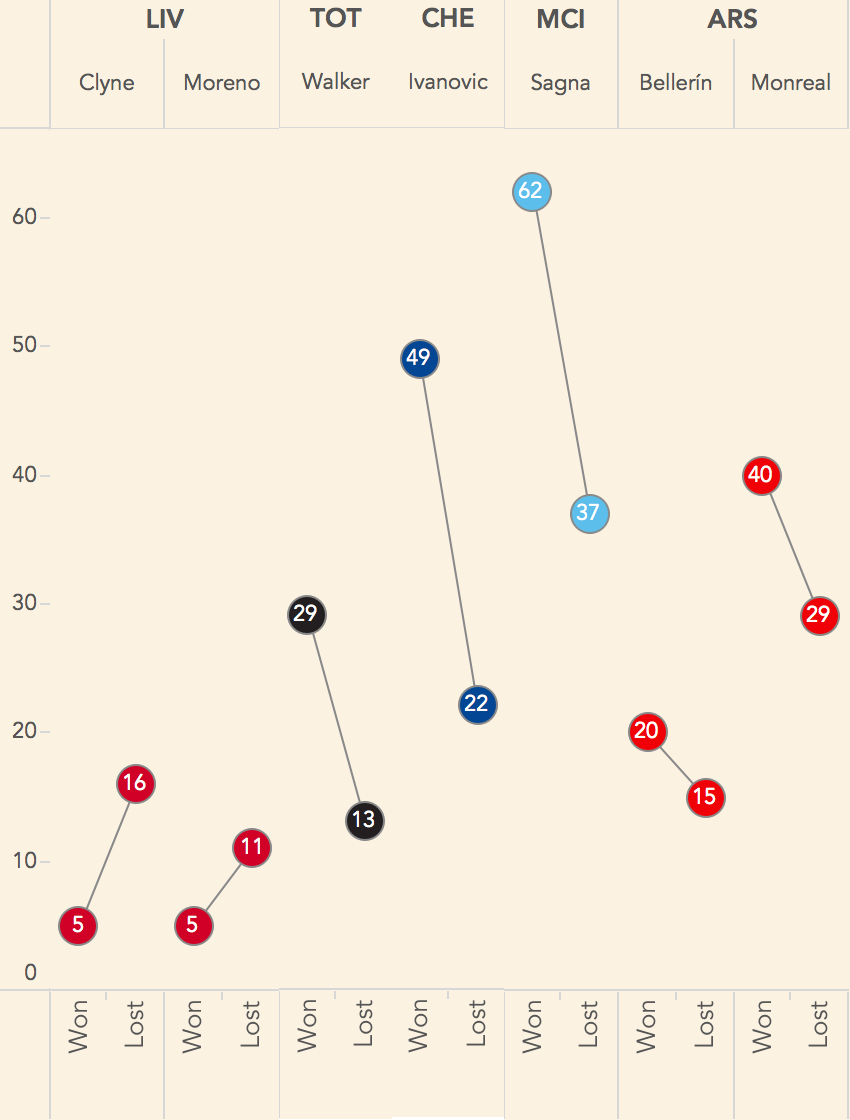

Unfortunately, Clyne and Moreno aren’t much better. They aren’t winning even one in every three aerial duels, and yet Arsenal’s full-backs, both 5’10”, are up around the 60% mark. Chelsea’s full-backs are between 56%-70%. Spurs’ Kyle Walker is just shy of 70%.

I managed to find 10 full-backs who were above 60%, with Ivanovic, Tomkins (the West Ham one, not me), Walker (Spurs) and Fuchs of Leicester all above 65%. So it’s clear that Liverpool have a massive weakness here, even if both Clyne and Moreno look like key parts of the quick, hard-pressing style Klopp is trying to implement.

Then you add Joe Allen (21% won), Jordon Ibe (33%), James Milner (36% at City, 36% at Liverpool) and Adam Lallana (30% over the past 18 months) and you’re looking at a whole collection of players who – mostly due to their height – aren’t very successful in the air.

Firmino is at only 25%, despite being 5’11”, although he’s still adapting, and has also played as a centre-forward, where the success rate is generally lowest (for example, Rickie Lambert is at only 37% for West Brom, and he’s 187cm, or 6’2”.) Three or four of these players often play, in addition to Clyne and Moreno. Yet Klopp has very few alternatives. A few of the (rare) taller players in the squad are out injured.

Look at Manchester United over the past 18 months, and they have ten players above 50% for winning aerial duels, including every single defender (bar Danny Blind), and only one player (Mata) below 34%. Liverpool have eight players below 34%. And while Moreno is just above this figure based on the past 18 months, this season he’s below it. This season Liverpool have both full-backs, plus a defensive midfielder (Allen), who barely win headers when he plays, as well as often starting with Coutinho, Firmino, Milner and Lallana – the best of whom wins only 36% of his aerial duels.

Even Emre Can and Jordan Henderson are only around the 50% success rate over the past 18 months – nothing special (50% being league average, obviously, in a situation where the outcome is always one winner and one loser). With almost all of the Reds’ other players down around the one-third mark (including all strikers bar Benteke), to be 50-50 is a big improvement on the alternatives. (Lucas is 60% this season, perhaps boosted by some playing time in defence, but only 45% last season; 52% in total.)

For contrast with some other central midfielders, Matic was c.65% last season, as was Coquelin. A smattering of midfielders get into the high 60s and early 70s in percentage terms (N’Zonzi and Glen Whelan last season, M’Vila and Shelvey this season), so it’s another area where Liverpool are well below average. Even Jordan Henderson wins slightly fewer aerial duels than he loses (47%), so one of Liverpool’s “bigger” players (still just below 6’0”) is not adding a tremendous amount in the air, but is at least better than Milner and Allen.

Liverpool have just five players (out of the 18 main senior players to heave featured under Klopp) who are above average in the air based on the past 18 months’ of aerial duels, and three play in the same position (so one will always miss out); and two of those are out injured right now: Lovren and Skrtel.

Right now, almost no one is compensating for the weaknesses in the air in both full-back positions, and when Kolo Toure is in the side it makes for yet one more weak aerial player (just 42% of duels won last season, which is horrible for a centre-back).

Even the forwards aren’t redressing the balance by any great amount: last season, for example, Balotelli and Sturridge were both in the low 20s (%), as is Origi (and as was Ings last season, although his Liverpool figures are not included, perhaps because he did not meet the minimum threshold of events). The one massive outlier is Christian Benteke, whose 56% at Villa has actually risen to 59% at Liverpool.

It’s harder for forwards to win a high percentage of duels, because they favour the centre-backs: after all, they are facing the play and looking to head in the direction the ball is arriving from, often just looking to get it up the pitch rather than to a team-mate. Then again, at set-pieces they should favour the attacking side, although in these situations defenders can become attackers and vice versa: often everyone goes back to defend, and every tall player goes up to attack (and although attackers can get a running jump, the side attacking the corners rarely sends everyone forward).

Considered Conclusion

Based on all this analysis, my recommendation would be that Liverpool buy some bloody big bastards.

They’ve brought in a couple already this January, with another linked (Matip), and more bloody big bastards should be right at the top of the transfer list. (Oh, and a goalkeeper too.)