By Paul Tomkins.

In this in-depth article, which is a kind of 2015/16 preview, I will look to answer some of the following questions:

• Can you buy too many players in a short space of time? Can a team be too ‘new’? Is player turnover too high at Anfield right now?

• Liverpool appear to have bought very well, but can a team be too young?

• What is the unique connection between each of Liverpool’s five best Premier League seasons? – and how does it relate to 2015/16?

• Are Liverpool outsiders for the title? Or is even the top four too high a bar to set? Much was spoken about ‘par’ last season, but what should par be for this season? – has it changed? And why does it remain a fair guide?

Along the way I will introduce some interactive graphics, to highlight the points I’m making. (Note: some coffee may be required for the journey.)

Part One: LFC’s Curious Case of Net Spends and New Players

Something odd happened in Liverpool’s five best Premier League seasons – those campaigns where they either challenged for the title, finished as runners-up, and/or posted a points total of 80 or greater.

It also seems to coincide with what Damien Comolli told Talksport recently, about the pitfalls of adding too many new players at once – but more on that particular aspect later. It all led me to analyse the approaching season from a perspective that I doubt anyone else will take, as I explain some precedents that seem to limit what the Reds can achieve, but also some which show what might just be possible.

The five seasons (Vivaldi’s long-lost work)

The five seasons in which I noted a surprising – but perhaps explainable – pattern were: 1996/97, when Roy Evans’ Reds famously finished 4th in a two-horse race (in mid-April 1997, after 33 games, his side were 2nd, just three points behind Man United, with a virtually identical goal difference); 2001/02, when Gérard Houllier’s side finished 2nd with 80 points; 2005/06, when Rafa Benítez’s side finished 3rd with 82 points; 2008/09, when the Spaniard’s side challenged for the title and finished 2nd, with just two defeats and 86 points; and 2013/14, when Brendan Rodgers’ side won 26 of 38 games in finishing 2nd with 84 points – taking the title down to the last game, and finishing the closest to the Champions (two points) that the club has managed in the past 25 years.

In all five seasons – in both the summers leading up to the campaigns, and during the seasons (or during the transfer window, once that was introduced) – Liverpool didn’t spend very much money in net terms. And that struck me as particularly odd.

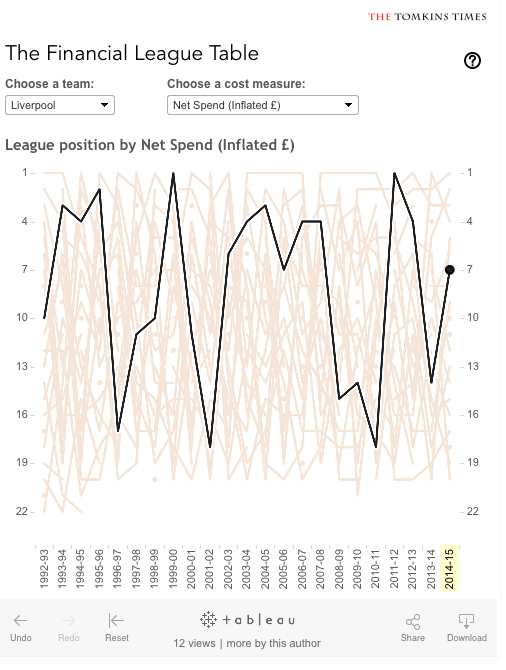

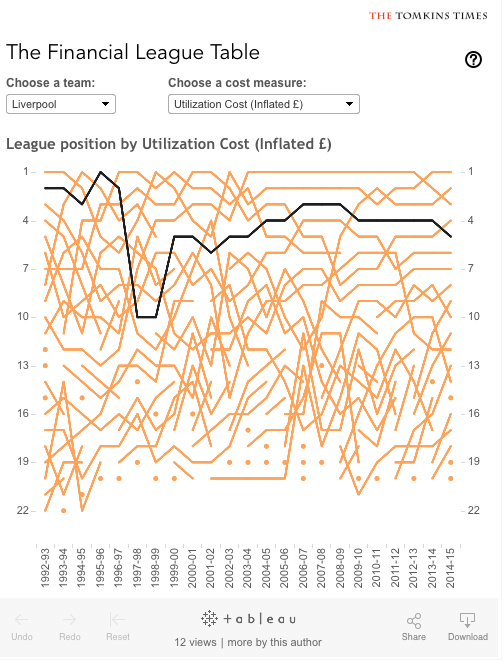

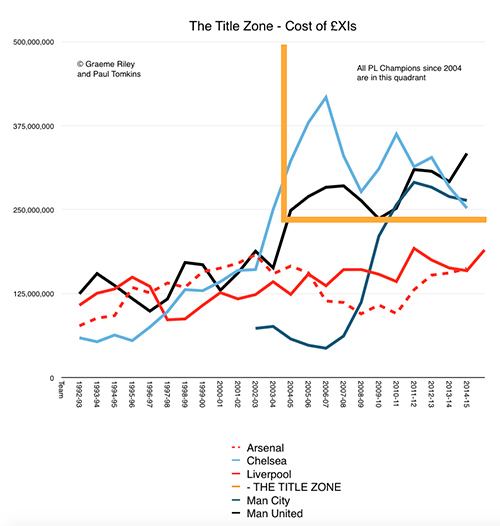

Adding to the reams of work by others, I have proved – in association with Graeme Riley, and our extensive Transfer Price Index – that money plays a big part in success (we proved it with transfer fees and inflation, others have proved it with wage bill data). check out Vice Sports this coming week for a piece I’ve written on the subject, and see the graphic below for just one quick example:

So why should this weird quirk appear with Liverpool’s spending?

I can think of two reasons that help explain it: the first is that net spend is unreliable, as I’ve been saying for some time now; and the other, which I will come to, is more intriguing, particularly given the club’s current approach to transfers – as hinted at by Comolli.

In addition to this, there are a few other precedents that Liverpool will have to overturn to challenge for the title in 2015/16 – if that’s what fans want or expect.

But first, here are some graphics – created by Robert Radburn with our TPI data – to show the seasons in question. The top one is interactive, whereas those that follow are screenshots. On the interactive graphs, you should be able to select any team, to make comparisons.

Quirks

For five years now I’ve been arguing that net spend is not a good indicator of league fortunes – it’s better than gross spend, which is hugely misleading, but net spend still relies on what can (or cannot) be sold, and often has arbitrary cut-off points. The cost of the team – the £XI as we call it on this site (that’s all 38 XIs of a club’s league season with inflation taken into account) – is far more telling; as is its wage bill (although no model is perfect).

However, net spend is interesting in terms of whether or not it gives a boost. In some ways a positive net spend can be seen like a shot in the arm, but it still depends on what resources were present to start with – a shot in the arm isn’t going to stir a corpse. A £50m net spend isn’t going to turn a preexisting £5m squad into title challengers, although it should make that team considerably better – if not ten times better (it doesn’t work like that, with the law of diminishing returns); but a £50m net spend by the reigning champions might be enough to keep them ticking over. Then again, the reigning champions might not even need to spend that much, if they’re in such good shape, and don’t have a lot of older players to replace.

So whatever the total of Liverpool’s net spend in any of these seasons, it was never going to tell the whole story – the £XI gives a clearer picture. Net spends often fluctuate wildly from season to season, whereas the £XI increases and decreases much less dramatically.

Still, it’s fascinating that these five seasons in particular show a really low net spend for Liverpool. There’s also the issue of how many of the brand new players made it into the team on a regular basis.

Dead precedents

While precedents don’t determine what happens in the future, they do show how success was achieved in the past. And until people break the usual patterns – and do so more than to simply be the exception to the rule – then it seems logical to suggest those patterns hold some meaning. After all, we’re not talking about random factors that have nothing to do with football, like the colour of the players’ hair or what their first name is. We’re talking about a lot of collective wisdom, not nonsensical coincidences, that have gone into them ending up at the best clubs.

To my mind, precedents provide a healthy guide. For example, take the fastest man on the planet. This appears in a Guardian article from 2012.

Is Usain Bolt’s height really a disadvantage?

Bolt stands at a statuesque 6ft 5in – which can, according to which expert you listen to, be a help or a hindrance. On the one hand his long legs help propel him to the front of the field; on the other, a shorter sprinter is able to move from a crouched position to upright quicker – and so can be faster off the blocks. Bolt’s start technique has caused him problems, though he says he has been working hard on improving it. Bolt’s height allows him to hold speed for longer and decelerate at a slower rate than a shorter sprinter. And his lean frame also helps, according to Professor Alan Nevill from the University of Wolverhampton, which carried out a study looking into the evolving body type of sprinters. “The sprinters with the leaner, more linear body shapes are gaining advantage towards the second part of the race,” he said. “They can keep up with the more powerful, bulky runners who get the explosive starts and then have a longer stride after about 40m to 50 metres. I believe the longer stride is showing benefit in the latter part of the race.”

At 6’5”, Bolt seems too tall to be a sprinter, but it’s also fair to conclude that someone who stands 7-feet tall would surely be too awkwardly proportioned to be as quick. Equally, someone who is only 5’6” would have a far shorter stride, and surely be too slow over that kind of distance. Until these parameters are broken, I’d say that there is an optimum height for being a sprinter – so the ten fastest men in the world probably average around 6’2”, with Bolt an outlier. (The 100m world record holders since 1977 range from 5’9” to 6’5”, with the most recent Bolt, at 6’5”, and Asafa Powell, at 6’3”. Justin Gatlin is 6’1”, and it’s 13 years since someone under 6’ held the record.)

However, this doesn’t mean that anyone over 5’6”, and under 7-foot – or who averages 6’2” – is therefore able to win the Olympic gold. It just means that someone of mere average height probably won’t be the quickest man in the world, and that anyone below average stands little or no chance. The fastest runners’ height is not a mere coincidence in their success.

Equally, spending billions on wages in and of itself won’t make you a great team unless you spend that money wisely. Teams with high squad costs and big wage bills still occasionally falter; but equally, the successful Premier League teams in the past 11 seasons have all had high squad costs and big wage bills (because there’s three of them, and all three rarely falter at once). Until someone eschews money and achieves Premier League success based purely on coaching or youth development, or with an analytics tool that helps them bamboozle the rest by finding hitherto undiscovered world-class players, then the precedents will hold some water.

A lot of collective wisdom goes into how much players cost and how much they get paid, so it’s not like – to use an example I was quoted – anyone is going to pay Adam Bogdan £5m a week. Anyone who did that could not have been working in football for long, and would not continue to work in football for long.

That was an extreme example that was created by someone to show that paying higher wages can be meaningless. And of course, giving more money to average players isn’t going to make them better, just as spending billions on average players won’t make your team better. Success is based on the collection of a lot of coveted and highly-rated players – to whom large wages are awarded based on past performances and future potential; along with the procurement of the top managers, who want to work with the best players (and the best players demand to be paid the best wages, and so on).

With this is mind I thought I’d look back at some of Liverpool’s experiences, to add to the observations on the five seasons covered earlier.

Concerns

In terms of Liverpool’s upcoming season there are two areas of concern, based on the precedent of their spending in the past two summers. This does not relate to the specific players the club has bought, who, to me, seem to tick a lot of different boxes. It relates to two other issues: age, and team longevity.

For Liverpool to excel, the team will have to disprove past rules.

The first is average age. Using the modern era for the purposes of practicality in data collection (and the fact that it’s the “scientific age” of the sport), there have been 23 seasons in the Premier League period, each containing 20-22 teams. So that’s 466 “teams” (with a single team being all league XIs of one club in one season).

Of those 466 teams, just 4% have been as young as I anticipate Liverpool’s 2015/16 team being – and that’s if the Reds’ best players are available often enough.

Liverpool’s probable best XI for the coming campaign – Mignolet, Moreno, Sakho, Skrtel, Clyne, Milner, Henderson, Coutino, Firmino, Sturridge and Benteke – average out at exactly 25. The highest position in the Premier League that any team with an average age that low (or lower) has finished is 3rd (Leeds 2000, Newcastle 2003 and Arsenal 2008).

What’s telling is that the 12 players Rodgers has competing for seven places on the bench (or who might usurp members of the XI, depending on issues of tactics, form and fitness) are actually younger. Unless Kolo Toure gets a game – and that’s unlikely – then Lucas, at 28, is the oldest player to step in. (I’m assuming that Jose Enrique, like Rickie Lambert up until the weekend, is an outcast – just waiting to be sold – along with Balotelli and Borini).

Aside from Lallana, who Rodgers likes to select (but Firmino may edge out), the players who are perhaps closest to forcing their way into the XI, as things stand, are Can (21), Ibe (18) and Origi (20); although Joe Gomez, aged 18, was one of the stars of preseason.

They would all bring down the average age to something bordering on ‘experimental’. The same would apply if adding Lazar Markovic (21), although due to the number of attacking-midfielders-who-can-also-play-wide he looks a fair way down the pecking order right now.

If Lovren replaces Sakho – something I’m not keen on (but looks likely – then the average age increases by a fraction; but if he replaces Skrtel then it decreases by a greater amount. Lucas is younger than Milner (as is Joe Allen, who is the same age as Henderson), and Ings, like Origi, is younger than Benteke and Sturridge.

It’s not unthinkable that the Reds could field a team that would average an insanely low 23 years of age (Mignolet, Gomez, Sakho, Skrtel, Clyne, Henderson, Coutinho, Can, Benteke, Ibe and Firmino), and yet in terms of talent you’d probably have no objection to it being selected. The youngest XI in the modern era – when averaged across the course of all 38 games – is precisely 24 (Paul Lambert’s Villa in 2012/13, and David O’Leary’s Leeds United twelve years earlier).

The great question is then whether a team with an average age below anything seen in two-and-a-half decades of top-flight football (and maybe much further back, if ever seen at all) could overcome what generally seems to hold young sides back: naivety, and the obvious lack of experience, which can be most obvious when the going gets tough. Perhaps a club like Ajax in Holland could thrive in such circumstances, but in a financial super-league like England there’s a more brutal reality.

Are Liverpool fans prepared for another year experiencing “an exciting young team” ? Both Leeds and Arsenal – the two best performers since 1992 with teams aged under 25 – had their best players cherrypicked by richer clubs, although in Leeds’ case it was their own financial stupidity that caused the exodus (including Harry Kewell to Liverpool in 2003 and one James Milner to Newcastle in 2004). They messed up a promising project by overspending on signings (and goldfish); their young homegrown stars (Kewell, Milner, Smith, Hart, McPhail, Carson, et al) were not the problem. It’s hard to know whether that team could have been kept together, had the club been better run, and what they might have achieved. But it yet again comes back to all clubs being vulnerable to wealthier rivals.

Then there is the sheer newness of this Liverpool team; and indeed, pretty much the entire squad.

It makes sense to see if this Liverpool side can mature together, but before it gets to reach “peak” age there will be further exits. The hope, for fans, is that enough of the better players remain, as they approach or hit their mid-20s, and that there is an average time spent at the club greater than the current figure of just two years.

It’s all so new

Going back to the five aforementioned seasons when the net spend was low, it’s interesting to note that most of those new players who did arrive failed to make it into the top appearance lists.

In 1996/97, neither of the two new signings – Patrick Berger and Bjorn Tore Kvarme – were in the top 10 for the club’s appearance makers. In 2001/02, just two of the new signings – John Arne Riise and Jerzy Dudek – were regulars. In 2005/06, only Pepe Reina was a stalwart, with Peter Crouch and Momo Sissoko ranking 10th and 12th respectively for overall appearances. (Daniel Agger, who arrived in January, was eased in, with just four games.) In 2008/09, only Albert Riera, from a handful of new arrivals, played more than half of the games (28 of 55). And in 2013/14, only Simon Mignolet (2nd) ranked in the top 12 appearance makers.

Now, a lot of these new players – across all five seasons – simply weren’t up to the required standard, or never quite adjusted to their role (or the expectations that come with the shirt). Others suffered injuries, or were only ever intended as squad players, there to provide insurance that was never really called upon.

An obvious response is: had these signings been better, then the Reds might have won the title in one or two of the given seasons.

Well, yes – but it’s always easy to say that. My argument is always that bad recruitment spells happen, and no one gets close to the magical 100% success rate; some years your signings work out, and some they don’t, and it’s not always obvious or predictable – before we add the wisdom of hindsight – as to who will succeed and who will fail. (For example, Chelsea buying Shevchenko and Torres: world-class, supposed peak-years’ players, one of whom had Premier League experience; or the “top, top” players United signed last summer, in Di Maria and Falcao, who were little better than Lallana and Lambert but cost a hell of a lot more.)

And people can always look back and say “if our transfers had been better” or “if our finishing had been better” or “if our defending had been better” – as if these things are easy to get right in unison. There’s usually somewhere that you fall short, and it’s never as simple to retrospectively correct that, and assume everything else stays the same. Any time you adjust anything in football there is a knock-on effect.

However, did the absence of new players actually help in those ‘successful’ seasons? It’s hard to say for sure, but could there be some type of correlation? Other seasons saw a greater number of successful brand new signings going into the XI, and yet these were the five best league campaigns. Why?

For example, 2007/08 is not remembered as an amazing season. Liverpool finished 4th, albeit with a fairly healthy 76 points (although they did better in the Champions League, where they reached the semi-finals). Nothing was won, but six of the top 11 appearance makers were signed in 2007, albeit two of them in the January, therefore six months before that campaign started. Still, that’s four of the summer signings, three of whom – Torres, Babel and Benayoun – were in the club’s top seven for games played that season. Liverpool were to become a better side a year later; ‘only’ making the quarter-finals of the Champions League but posting what remains the club’s best Premier League points tally – 86 – as the Reds improved by two league positions and ten points. Those 2007 signings played a fairly key role in finishing 2nd; the 2008 signings did not.

What’s also interesting is that Liverpool’s spending in the 12-24 months before these five ‘peak’ seasons was relatively high, as was the turnover of players.

For instance, in Houllier’s case the big spending came in 1999/00, with the treble of 2001 based largely on that earlier spending, and the 2nd-placed finish coming in 2002, still mostly with the 1999/00 buys at its core (Hamann, Henchoz, Hyypia and Heskey … Perhaps Liverpool should just sign players with a surnames beginning with H? This is of course a joke, lest anyone try and use this kind of silly argument.)

These four ‘H’s worked in tandem with three youth graduates – Carragher, Owen and Gerrard. For a few seasons, these seven were key first-XI players; and between 1999 and 2002 they were mostly under 25, and all under 28.

My sense here is that it takes time to bear the fruits of a big net spend; particularly if there is a high turnover of players. Many of the new signings of 1999 settled quickly – Hyypia was clearly a star from the start – but the team wasn’t as good in 2000 as it was in 2001 and 2002.

This brings me onto what Damien Comolli told talkSPORT, regarding Liverpool’s latest bout of acquisitions:

“I thought it was a huge risk last year after selling Suarez and bringing in, I think, nine. Now they have decided to change a lot again and totally rebuild. That is always a massive, massive risk. They have bought in players who have got talent, but they are going to compete against some very settled teams. Arsenal, [Manchester] United, [Manchester] City and Chelsea are making some very subtle adjustments to their squad and Liverpool are changing everything every year. I’m not convinced it is the right approach. It is too much in two off-seasons.”

The data seems to back this up, although there is one very notable precedent that suggests Comolli could be wrong; albeit a precedent (which I will come to) provided by a club in a very different situation.

Massive risk?

Many individuals – younger and older, foreign and homegrown – take time to settle; but equally, unless there’s some uncanny clairvoyance, a newly-assembled side won’t have the understanding of one that’s in its second or third season together. A wonderful new signing might provide some impetus, and add some freshness to what might otherwise be in danger of growing old or stale – but could keeping the core of a side together be a more crucial route to success? Are Liverpool taking a “massive, massive risk”, or will bringing in better players than already at the club – if that’s what the 2015 signings are – pan out for the best?

A high net spend involving young players may mean that the rewards are delayed, as potential can take time to blossom into top-level consistency. And yet I’ve no doubt that, on the whole, buying players aged 18-25 is a better use of resources than going for the perceived ‘finished product’ (not least because no matter how many ‘finished product’ signings I analyse, there’s no clearer success rate, beyond a very small increase; but with the added risk of overpriced fees, overly large wages and reduced sell-on options).

The catch-22 becomes that if you aren’t winning things it becomes harder to keep the core of an emerging side together, and that it’s harder to win things if you have no more than the core of an emerging side.

Cups (a very brief detour)

Of course, each season is different – and finding five similar patterns relating to spending and integrating new players does not mean that this will be the only reason why the Reds performed better in those seasons than in others.

In those five seasons Liverpool also played relatively little European football (compared with what the club was used to at the time), and not as much cup football in general. Only one of the five seasons resulted in a trophy, 2006’s FA Cup; indeed, it was the only cup final in these five seasons – whereas in the ten seasons either side of these five (so the one preceding and succeeding each) saw the Reds reach an astonishing ten cup finals.

Again, this suggests that unless you have a mega-squad, balancing the cups and the league is a near-impossible feat.

Research I published in May – looking at all clubs in the Premier League era – seems to prove that too much cup football can indeed be detrimental to a team’s league health. There are exceptions to all rules, of course; but that seems to be the general trend, and is more pronounced outside of the ‘rich three’ of Manchester United, Manchester City and Chelsea.

Newness

As noted earlier, the most likely Liverpool XI this season averages precisely 25 years of age and has just 2.1 full seasons at the club. So not only is it young, but it’s newly assembled.

It’s hard to think of a young side assembled in such a short space of time that has gone on to be successful – although there is one interesting precedent.

That precedent aside, there have been young sides where a clutch of homegrown players have come through the ranks over two or three seasons – although Man United’s mid-‘90s side was mixed with longstanding older pros like Cantona, Bruce, Pallister, Irwin and Schmeichel. But these situations – as also seen at Barcelona in recent times – often suggest that some harmony and synchronicity has been developed together in youth teams.

The successful Arsenal sides between 1998-2004 were built on a core of long-serving players; from the famous defence (mostly in place for a decade) and the likes of Ian Wright and Ray Parlour in 1998, to players like Vieira and Bergkamp, who were the elder statesmen by the time Wenger won what remains his final title in 2004. Chelsea’s champions of 2010 – the oldest to do so since the league was rebranded (average age just under 29) – had so many players still around from the 2005 and 2006 triumphs.

Blackburn assembled their side – one of the youngest champions of the past two and a half decades (25.5) over a slightly longer period of time than seen at Chelsea and City, not least because they were starting in a lower division; with an average of 2.5 full seasons at the club before the famous 1994/95 season began.

There have been youngish sides assembled in double-quick time, but these – Chelsea and Man City – were playthings of two of the richest men in the world, with unparalleled short-term investment (even greater, relatively speaking, than seen at Ewood Park two decades ago). Chelsea and Man City were buying large numbers of elite and often established talent, and discarding the many who didn’t make the grade (often also big names), no matter what they had cost. Liverpool don’t have that kind of money.

(As another quick aside here, someone took me to task on Twitter saying that Liverpool are surely richer now than the club was under David Moores in the mid-‘90s, not least because of the TV deal money, and the fact that the club are now in the top 10 of world football finance. I pointed out that in relative terms, the Reds were very rich 20 years ago – they broke the British transfer record in 1991 and 1995, and started the Premier League era with the 2nd-costliest side in the league, behind only Manchester United. And yet last season Liverpool had the 5th-costliest £XI, the 5th-highest wage-bill and were the country’s 5th wealthiest club in the Deloitte Football Money League rankings. It’s one thing to be the 9th-wealthiest club in the world; it’s another to be behind four other clubs in your own country. Liverpool are “richer” than Juventus, but Juventus are the richest Italian club, and that is in part why they win their league and guarantee continual Champions League qualification.)

Between 2003 and 2005 Chelsea bought no fewer than 18 senior players who each cost between £12m-£60m in today’s money – amounting to an astonishing £671m after TPI inflation. Remember, this was over a decade ago, and even without inflation it came to £209m in a 24-month period – and that’s when players on average cost only a third of what they do now. Half of the 18 were either flops or unremarkable, but the other half helped win those coveted league titles.

The 2005 vintage remain the Premier League era’s youngest champions, at 25.2 – but with the likes of Arjen Robben and Petr Cech – they were full of higher-end purchases than Liverpool are now making. And they still had a core of players in their mid-20s – Lampard, Terry, Gallas and Guðjohnsen – who had four or more years at the club. Even so, it was largely a brand-new project: the eleven top appearance makers for them that season averaged just 1.8 full years at the club at the start of the campaign. (By contrast, Mourinho’s recent title-winning squad had an average of over three seasons at the club before the start of the campaign.)

Man City’s 2012 title was achieved with an average age of 25.7 – so still pretty young, and in the ballpark of both Blackburn and Chelsea’s initial breakthroughs. And they had an average of 2.1 full seasons at the club – exactly the same as Liverpool’s current (mostly likely) strongest XI. In City’s case, the defence – where understanding is arguably more important than the improvisation of attacking – was actually fairly well established: an average of four full seasons between Hart, Zabaleta, Richards and Kompany, with Gael Clichy the one regular new addition.

City’s route to the top took a bit longer than Chelsea’s, as they weren’t already in the Champions League. Between 2008 and 2014, and with inflation added, City spent one billion pounds on transfers (or almost £700m without inflation). In that time they spent £406m on duds, rejects and underwhelmers (£300m without inflation. And in fairness, a couple of these duds still remain at the club and may turn their fortunes around). They spent £440m in today’s money in what turned out to be fairly successful or very successful purchases (£288m in uninflated money; the uninflated amount being cheaper on account of the successful buys mostly taking place between 2008-2011 – which makes them slightly more expensive in 2015 money, on account of the market conditions during the time of purchase). They also spent £130m (£100m uninflated) on players who did little better or worse than okay.

City’s successful buys averaged 24.5 years of age, and the flops averaged 24.8 years of age – much the same. And yet the mediocre bunch averaged 26.9. The success rates – roughly 50-50 – fit in with my “Tomkins’ Law” theory of transfers, but as with Chelsea a decade earlier, success was in part due to the way City could write off a high number of expensive duds without it limiting the amount of expensive new players they could gamble on (although FFP has slowed this, and Chelsea have also learnt to live within their means).

If you go back through all the other successful teams – especially those that didn’t inject unprecedented sums into the squad – then I’m pretty sure you won’t find a lower average age than Liverpool’s likely XI this season, nor a shorter period of time spent at the club. So as I said, this is experimental. As explained, there are some precedents, but they were achieved with a higher number of elite-level buys who were far more expensive than what the Reds have acquired.

Having said that, Liverpool (presumably?) aren’t looking to win the league this season. If breaking back into the top four is the aim, then there have been eight occasions where a team averaging 24-25 years of age has finished 3rd or 4th. So it’s possible – but of the 92 top four places since 1992, just 8.7% have been occupied by a team this young; and of the 46 top two spaces, it’s 0%. Of course, theoretically, if you had a team comprised of the world’s best XI 23-year-olds you could expect do better; but this is an unlikely scenario for any club.

But all this is based on Liverpool being able to field what I believe to be an approximate best XI. And this almost never happens.

Where Liverpool would almost certainly break new ground is – where this could get very interesting – is if Martin Skrtel gets injured. Then, Jordan Henderson, with just four full seasons, then becomes the longest serving player in the starting XI. Let that sink in for a minute.

Unless Lucas Leiva comes into the side, it will likely average around just 1.5 full seasons at the club; and with Lovren presumably replacing Skrtel (if/when the oldest first XI player is injured) alongside Sakho, there’s a very real chance that the average age of the side could be below 23.

Indeed, I managed to pick an XI with eight full internationals, plus Can, Gomez and Ibe, that averaged just 22.4 – which seems utterly insane. Given that players can often play U21 football up to the age of 23, this is essentially an U21 side.

Part Two: closer to the Title Zone

Liverpool’s probable strongest XI projects them closer to what I termed the Title Zone: the minimum cost of every champions’ £XI (the average cost of all 38 XIs in a season, adjusted for inflation) from 2004/05 to 2014/15.

While the Title Zone doesn’t say that this amount is definitely required for a team to succeed, it’s a pretty strong precedent.

Inflation actually means that the Title Zone – which was £210m in 2014 money – has now risen to £236m. This is because 2014 money is less than 2015 money, given that prices have sharply risen once again. If you bought a player for £20m in 2011, in terms of the transfer fee paid he is essentially now a £35m player; as that’s what the equivalent cost would be to buy him this summer. So in 2015 money, the cheapest title-winning £XI since 2004 is £236m (the most expensive is over £100m more than that).

Even so, Liverpool should move a little nearer to the Title Zone than they were last season – assuming that the best players stay fit. This is based on the team containing Firmino, Benteke, Henderson and Sakho, all of whom cost over £20m in 2015 money (not least because two of them were bought with 2015 money; even the slowest readers out there should pick that up). Add Sturridge (£19.5m) and you can see the quality that money has bought.

The average cost of Liverpool’s XI last season (the £XI), in 2014 money, was £142m. That same £XI in 2015 money now equates to £159m, but obviously the other 19 clubs’ £XI rise by the same factor (although players bought in 2014/15 do not yet have inflation applied; 2015 money is calculated at the end of the 2014/15 season, and this summer’s deals will contribute to 2016 money).

What I believe is Liverpool’s strongest XI now costs £190m, after inflation. So even though the Title Zone threshold has risen by 12.3% with inflation, the cost of Liverpool’s best XI has increased by 19.5%. Obviously where problems arise is if those better players get replaced in the XI by cheaper squad players; so by May, Liverpool’s £XI could still theoretically register around £160m. Or if things get really bad, even lower. (Remember, the £XI is not the best XI, but the average cost of all 38 XIs.)

Of course, add Lovren (£20m) instead of Skrtel (£12.6m), and the team arguably gets worse, but costlier. The most expensive theoretical XI I could concoct – with everyone in their correct positions – from Liverpool’s current squad is £233m; so still not quite in the Title Zone.

This shows the downside of suggesting every player is worth what is paid; obviously a lot of players are not, and any club’s most expensive signings will still probably have a 50-50 hit/fail rate. (Eight of the 16 most expensive Premier League-era signings, when adjusted for inflation, were clear flops.) But as noted earlier, the fees are built on logic and assessment, and are (mostly) not arbitrary amounts plucked from thin air. And players can also be worth more than was paid for them, not just less. So some balancing-out occurs.

Excessive Hit Rates and Excessive Flop Rates

The £XI, as a predictive tool, works fairly well on account of this balancing out – particularly when it’s across a large number of expensive signings. It can occasionally be horribly wayward, in terms of what a club ends up thinking a large number of players are worth; so, for example, when the Blackburn team assembled by Roy Hodgson got relegated in 1999, shortly after he was fired, it remains the costliest £XI to suffer that fate. It was a horrible misjudgement. While Hodgson did very well at Fulham and West Brom, his time at bigger clubs (as Blackburn were back then) was fairly disastrous.

In today’s money, signings like Kevin Davies (£28.3m), Christian Dailly (£20.7m), Sebastian Perez (£11.7m) and Nathan Blake (£16.6m) – £77m on four 1998 arrivals – helped do nothing more than root Rovers to the foot of the table. And although Brian Kidd improved them in the second half of that season (better points per game, raising them one league position in the process), the further £70m (TPI) he spent on Ashley Ward, Matt Jansen, Jason McAteer, Lee Carsley and Keith Gillespie, to try and buy Rovers’ way out of trouble, just meant that £150m in 2015 money was very unwisely invested. In hindsight, those players as a collective weren’t even worth half of what was paid.

However, in the new millennium there is usually a much greater wisdom at work at the richest clubs; indeed, it was seen at Blackburn 20 years ago, before Hodgson arrived. For all Kenny Dalglish’s perceived faults as a modern-day manager, he bought some exceptional talent between 1985 and 1995. In today’s money, the collective of Alan Shearer, Chris Sutton, Tim Flowers, David Batty, Henning Berg, Tim Sherwood, Stuart Ripley and Graeme Le Saux – bought between 1992 and 1994 – cost virtually the same as what Rovers paid in that single ill-fated season under Hodgson and Kidd, and helped them to the title.

And whereas the £150m Kenny Dalglish spent on the eight big successes on way to winning the title was turned into £200m with sell-on fees (win the title, make £50m profit when selling the players), the £147m spent by Hodgson and Kidd recouped a horrific £29m, for a loss of £118m. (Dalglish also signed a few flops between 1991 and 1995, although they only cost around £30m combined.)

Dalglish’s Blackburn bucked the 50-50 success/failure transfer rule, but it was an era of fewer squad players, who now “fail” by definition of being barely used. Dalglish’s best Liverpool side – 1987/88 – also bucked the trend, in terms of an incredible hit rate; something that the Scot could not maintain later in his first tenure (albeit directly after Hillsborough).

However, 1987/88 also touches on the issue of whether a number of new players disrupt the flow. Interestingly, the spending that had a near 100% success rate – Aldridge, Barnes, Beardsley and Houghton – was split between January, June, July and October; with Nigel Spackman – only a short-term success – arriving in February 1987. So Aldridge was already settled (if not really scoring) by the time Barnes and Beardsley arrived in the summer, and Houghton was added 16 games into the famous 1987/88 season; five key players in that campaign (Spackman played 27 times in the league), but each phased into the club at different times during the calendar year.

The biggest clubs now have all kinds of experts to identify and procure elite players. And although they still often end up with the same circa 50% success/50% fail rate from shelling out big fees, they fill their teams with the top-class buys that come off, and aren’t bankrupted by the 50% that don’t. They keep Drogba and write off Shevchenko and Torres and Wright-Phillips; they keep Rooney and write off Veron and Anderson and Di Maria; they keep Silva and write off Robinho and Jo and Jovetic; and so on. (Even so, the collective wisdom means that they are not having to choose between keeping Kevin Davies and Nathan Blake.)

On average, an £XI will be roughly half of what the club’s squad costs in current money. In other words, most seasons will result in a club not using half of its expenditure in the starting XI. (My TPI co-creator, Graeme Riley, wrote about Wastage here: on average over the past 23 season, only 52% of all club’s squad costs have been reflected in their £XIs; for the past dozen champions it’s been 55% utilised, 45% “wastage”.)

Of course, it also depends on those more expensive sides being managed in the correct way; put a monkey in charge and you’ll get chaos (and some bananas). But the richest clubs tend to make sure they have the world’s elite bosses; and when they don’t, as seen with United and David Moyes, they can fall below expectations.

Spending sprees

Since 2010 Liverpool have spent approximately £550m in today’s prices on over 50 players. But they’ve also recouped over £300m in 2015 money in the past five years; which means that (as was the case under Rafa Benítez), the squad was never expensive enough at any one point to be able to select a consistently expensive XI. (And obviously none of the current squad have been sold; that’s over £300m in expenditure.) It’s a continual process of selling in order to try and improve, or selling because the players were unsettled by bigger and/or richer clubs (Mascherano, Torres, Suarez, and now Sterling).

Before the outcasts like Borini and Balotelli are sold (assuming that they can be), Liverpool’s current squad costs £384m in 2015 money, and, bar some unexpected signings, is likely to drop below £350m by the end of the window, once the deadwood is cast adrift.

The Rich Three have squads that cost in excess of £600m. The law of averages suggests that picking a strong £236m side from that is easier than doing so from one costing £350m.

So for Liverpool to be title winners – if people think it’s possible – they’d have to essentially find that 70% of the money spent on current squad costs work out exceptionally well; but for City, United or Chelsea to do so, they’d only need have less than 40% to field an £XI that costs £236m – the Title Zone starting point since 2004.

They have far greater insurance policies, and these kick in during periods of fatigue, injury and suspension. If Liverpool could get 70% of their signings (or 70% of the money they invest) spot-on, it would be breaking all general precedents. However, as shown with Dalglish at Liverpool (first time around) and Blackburn, the laws can be broken on a short-term basis.

But if Liverpool did just that – and hit a 70% success rate – it would still theoretically put them at a disadvantage over the Rich Three if those rivals only got 50% of their investment spot-on.

Does the Title Zone hold water?

Of course, most people could theoretically assemble a title-winning side of purchases that cost under the ‘magic’ £236m that has been required to win the league in the past 11 seasons. For ‘just’ £200m I could assemble, in theory, the XI of Hart, Zabaleta, Kompany, Cahill, Ivanovic, Schneiderlin, Fabregas, Coutinho, Silva, Sturridge and Costa, based on those players’ Premier League performances in the last two years. With a decent manager that lot could probably win the league.

But what are the odds of buying eleven players that good? If doing so with just eleven signings – with just £200m to spend – I’d say 0.1%, at a random guess. And if you took those eleven players to a new club, which automatically changed the dynamics involved, some would suddenly struggle, while others may get serious injuries.

You’d probably need to sign 30 or 40 players to end up with that level of team for that kind of budget, and even then I think it’s highly unlikely. Every successful Premier League team since Wenger’s Invincibles has had to throw in a greater number of £30m-£80m buys (in 2015 money) to bolster the side and boost their odds. Only four players in my mythical side cost more than £20m, and none more than £36m (Silva). No one unearths such a high number of cheap future superstars at such a success rate – or if they do, it’s a freakish outlier.

What are the odds of getting a goalkeeper as good as Joe Hart? Maybe 10%; perhaps an elite Premier League club could buy one of the few comparable talents in world football (such as David De Gea, Petr Cech and Thibaut Courtois). But what about getting some as good as Hart for just £1.6m, which is what Hart cost in 2015 money, and is part of keeping my side at £200m? Maybe 1% at best.

After inflation, Courtois cost £13.8m, Cech £28m (to Chelsea, in his prime; or £13m to Arsenal aged 33) and De Gea £32.6m. So you’re instantly highly unlikely to be able to fashion an elite team for as cheap as the hypothetical one I listed, because no sooner do you start than you find filling the first position on a budget almost impossible.

How many centre-backs would you have to sign to end up with one as good as Kompany for the £8.1m he cost after inflation? Or even £30m? It’s almost a one-in-a-million buy; on a par with the equally cheap Sami Hyypia in 1999. City then threw £38m at the position with Lescott and £42m with Mangala, and couldn’t repeat the ‘lucky’ shot they had with the Belgian. If they could repeat it, they would; but it was a freakishly good bit of business.

Aside from players who’ve come through the system (like John Terry and Jonny Evans), the average price of a title-winning centre-back, in 2015 money, is more than Liverpool have ever paid for one.

You get the incredibly cheap buys like Kompany at one end of the spectrum – exceptions to the rule – and the other end contains Rio Ferdinand, £82m in 2015 money (think of how costly he was in 2002, at £30m), Carvalho at £60.5m, and Lescott at £38m. In the middle is someone like some-time centre-back Ivanovic, at £17.5m. These seven ‘purchased’ centre-backs who helped win their clubs the title in recent years (as regulars in the position) cost £32m on average.

Again, this is just one position. What about the average cost of the recent title-winning strikers? – Rooney, van Persie, Tevez (at City), Drogba (when bought in 2004), Costa and Aguero average out £56m apiece. These are the successful ones their clubs kept to win those trophies, but they still spent similar amounts on players who had a similar pedigree but didn’t prove as successful (Torres, Adebayor by City, Dzeko, Robinho, Shevchenko), all of whom ended up as squad players or were sold for big losses.

The average price of that ‘failure/squad player’ quintet in 2015 money? Also £56m. So these clubs are often paying £56m for hits as well as paying £56m for duds.

And what are the odds of my hypothetical team staying fit for all 38 games? I’d say zero percent, especially with some of those eleven being injury-prone, and given that no team has stayed fit for a whole season in the modern era. So then, unless you have a rare crop of homegrown talent (think United and Liverpool in the ‘90s), the squad players need to be of a sufficient quality, and then we’re back where we started, in terms of what they cost.

Again, it all comes down to odds and probability. We all know that in the Rich Three squads, as well as Liverpool’s and Arsenal’s, there are players where the investment – such as with Lovren at Liverpool – currently falls below what has been hoped for, and so that’s £20m spent on a player who, if everyone is fit, probably doesn’t play (although this is a new season and Rodgers seems prepared to give him another try; something I’m very uneasy about, whilst accepting that centre-backs are usually at their best between 25-33, and plenty of players come good in their second season).

In a sense, Liverpool can only afford fewer such buys – because a greater proportion of the money spent has to go into the XI in order to compete. Richer clubs can afford more Lovrens without denting the first XI.

And yet the Rich Three are also spending bigger individual sums than Liverpool; and the more you pay for a player, the greater the chances of success (but the difference tends to be increased odds of just 10-20%; you may get a 50-60% success rate with the mega-buys, rather than 30-50% at the lower end of the market).

Players like Rooney, Aguero and Hazard are more expensive, after inflation, than anyone Liverpool have bought in the Premier League era; as are 16 other signings (weirdly, two of which were made by Newcastle: Shearer and Owen).

With the addition of Sterling, City currently have eight players who cost over £34m in today’s money; Chelsea have three (but several who cost just below); Man United have four including Di Maria, who looks set to leave (with seven more who cost in excess of £28m); Arsenal have two; Liverpool have none.

Even with inflation, the £32.5m the Reds have paid for Benteke makes him the squad’s most expensive Premier League player. (Liverpool have signed eight others since 1992 who cost more, but they were all sold at some point; Carroll, who cost £50.5m, was the most expensive, with Cissé and Heskey ranked 2nd and 3rd.)

Following on from Benteke, and again accounting for inflation, Firmino is the current squad’s 2nd-costliest player in 2015 money, with Henderson, at £27.6m, third. Chelsea have seven players more expensive than Henderson in 2015 money, City have nine, and United have twelve.

While this is just a guide, it’s important to note, once again, that Chelsea and Manchester City broke from also-rans to title winners not by simply employing better managers with clever tactics and advanced fitness methods, but by investing heavily in players (something Alex Ferguson also did between 1988 and 1992, which probably coincided with his best success rate). All this investment in players predated the title wins – so in this case, the egg came before the chicken. (And the same was true of Arsenal’s title successes under Wenger, before they went from having the costliest £XI in 1998 and 2002 to one always outside the top three.)

Obviously now it’s more of a virtuous cycle for City and Chelsea: success on the pitch is providing them with new financial rewards. But they only entered the Title Zone with immense investment.

Damned If You Do…

Whatever way you approach your transfer policy – buy for now, buy for later – if you have richer competitors who can unsettle and steal away your players, there’s probably a ceiling to what you can achieve; again, something I’ve spent a lot of time illustrating over the years. (And the greater the number of richer competitors, the worse your odds of ultimate success, on account of the need for a greater number of rivals to have bad seasons. As brilliant as Atletico Madrid were two seasons ago, both Real Madrid and Barcelona had uncharacteristically poor league points returns, approximately 10 points down on the average of the previous past five seasons; and normal service was resumed in 2014/15.)

If your players (and team) does really well, like Suarez and Liverpool in 2013/14, you can still lose that player; and if the players (and team) does poorly, like Sterling and Liverpool in the final third of 2014/15, you can still lose that player. If you aren’t super-rich, or über-glamorous, you can always lose the player, particularly in the age of player-power and agents who make Bebe Glazer look like an angel.

On both occasions – Suarez and Sterling – a richer club with recent league titles and consistent Champions League qualification lured away key performers. Despite Liverpool playing hardball, the club knew that it was essentially powerless to stop these exits. (The danger with banishing want-away stars to the reserves – as much as I’d like to see it done – is that instead of sending a message of strength, it could be interpreted by existing players – and potential future players – as an unfair tactic, given that, funnily enough, players see things from a player’s point of view. Liverpool played hardball, but ultimately they didn’t strong-arm the player into submission. And obviously, £49m to reinvest can make more sense than no money and, with him banished, no player.)

Conclusion

I’ve written extensively this summer, elsewhere on this site, about the individuals Liverpool have signed and what they can offer, so I didn’t want to go over that again; other than to reiterate that I like the different options the wide range of signings potentially offer. I think that Brendan Rodgers now has more options, and that Benteke, in particular, can mix skill and pace with brute force.

It all means that Liverpool are left with a new, young squad, full of what seems like great potential, but which has come at the cost of selling two of its best players in the past 12 months (along with losing Steven Gerrard, no less! – albeit after his legs had inevitably gone.)

However, if enough of what amounts to £124m for just two players is reinvested wisely – and it’s highly unlikely that it all could be, no matter what the transfer approach (and we already know that some of it hasn’t) – then the Reds can still thrive within relative terms. (I know the £124m didn’t come in one lump sum, but the point remains.)

If, from that £124m, Emre Can and Divock Origi – bought last summer for c.£10m each – develop into world-class talents within the next year or two, and Nathaniel Clyne continues to progress into an outstanding right-back, and Roberto Firmino translates his Hoffenheim form into a red shirt, then that will still be only half of the £124m received for those two players Liverpool would have ideally kept but were essentially forced to sell. It’s not unthinkable that those four could be real difference makers; big delivers.

Add one more successful signing out of that money – say Lazar Markovic or Adam Lallana, if they improve, or Christian Benteke if he fulfils his potential – and then, even if you wrote off £40m of the £124m, it could theoretically make for a better side than keeping Suarez and Sterling would have done. It would mean outstripping the Tomkins’ Law success rate, but it can happen.

Selling your best player doesn’t have to lead to decline; sometimes it does, of course, but at others it helps spread the talent wider across the XI and the squad, to make for an overall improvement. Again, to return to the 1987/88 exemplar, Ian Rush’s departure should have been a hammer blow, and yet it was turned to the club’s advantage. The same was true ten years earlier, when Kevin Keegan left, and Kenny Dalglish replaced him.

Perhaps the problem Liverpool had last season was that six or seven of the new players were either simply not good enough (bad judgement calls) or still acclimatising/adjusting/developing. This meant that, overall, no single position was actually improved; and that, indeed, the loss of one outstanding player in a pivotal position (such as centre-forward), was in this instance more harmful than buying various options – at least for the short-term of one season (these players are still at Liverpool and can yet improve; indeed, some almost certainly will).

But let’s add here that last season was more complicated than that: Daniel Sturridge’s injury; Steven Gerrard’s decline and departure, and the carry-over of the whole slip-gate nonsense; the psychological blow of losing Suarez and, indeed, the league title; so many players at the World Cup; Raheem Sterling’s escalating disenchantment and its unhelpful public airing; the steep increase in the number of cup games; the young average age of the XI most weeks; the spell where Mignolet got so bad that Brad Jones became no.1; the mixed tactical experiments; and the fact that wherever Mario Balotelli goes the team soon falls apart, which, as much as I wanted him to succeed, gets harder and harder to put down to coincidence.

The new signings either suffered because of these other issues, or they added to (or created) many of the issues themselves, either by their lack of talent and/or suitability, or just by being one more new component in an unfamiliar side getting to know each other. (And in fairness to Brendan Rodgers here, he started the season by gently blooding the new buys two or three at a time, before injuries meant they all ended up thrown in together. In the early game at Spurs everything looked perfect, but then it fell apart.)

A year on, maybe it’s time for at least half of these signings to push on (some will simply push off). Some – such as Adam Lallana, Lazar Markovic and Dejan Lovren – will feel a bit less burdened by their price tags, especially as more expensive players – Firmino and Benteke – have arrived (although that of course simply transfers the pressure to them). Some, like Can, Origi and Markovic, will be a year older, which makes a lot of difference when so young. (Moreno is already slightly older, but the same applies.) In Origi’s case, simply being in Liverpool will be an upgrade on what he offered the club last season, which, due to the loan agreement, was nothing.

Some – particularly Lallana – will hope to have fewer niggling injuries (the same is true of Sakho, two years in). And the ‘homegrown’ teens who broke through last season – particularly Jordon Ibe – can easily become twice as effective within a very short space of time. And perhaps the prodigious talents of Sheyi Ojo and Pedro Chirivella – and/or one or two others – will turn them into handy squad players, if they aren’t loaned out for vital experience.

Not all of these positive outcomes will transpire, of course, but some should, and that might be enough to help improve the team; just as youngsters coming through during Graeme Souness’ tumultuous tenure were only sufficiently matured by the time Roy Evans was in charge, and were then part of a team that then challenged for the title in 1997. If Liverpool’s new summer signings settle quickly, as they did in 2007 or 1999, then the team could improve radically – although it may be the season after, as happened in those cases, when the team started to really purr.

The downside of the current project succeeding is that there will probably be just one shot at it. Then the next group of vultures will be circling. If he excels, Firmino will be on Real Madrid’s radar; if not him, then Coutinho. But we should enjoy these players while we have them, and hope that – somehow – it all comes together just how we’d wish.

Subscribing to TTT helps us to maintain the site, pay various contributors and provide free content to those who can’t afford to sign up. It gives you the chance to interact with the writers and editors, and other smart people, as part of a troll-free discussion environment.

Alternatively, buy our books to support our work, including my new anthology.