By Nick Haley (TTT Subscriber NoWorkinForFergie).

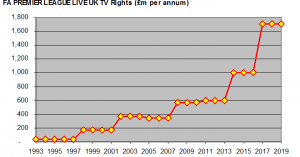

Shortly before negotiations started for the live broadcasting rights for the newly formed FA Premier League (FAPL), our adopted Jamaican wing-wizard John Barnes reportedly became the first football player in England to be paid £10k a week – his reward for being the finest player in English football playing for the finest team in English football. BSkyB subsequently agreed to pay £38m per year to the FA for the UK broadcasting rights.

Fast forward twenty plus years and to secure the same UK live broadcasting rights for the three seasons from 2016/17, Sky and BT Sport have committed to pay £5,136m, or £1,712m a year. Add non-live, overseas and commercial revenues and you’re around £2,500m a year flowing to England’s top tier football clubs, just from the FA.

In a world where we are bombarded with large numbers every day, maintaining any sense of context for what those numbers mean is incredibly difficult. The 2016/17 number is not a 45% increase on the Premier League’s inaugural season, it is forty-five times that amount. That figure takes some processing.

Time addles the brain, just like big numbers do. Comparing 2017 to 1992 is stretching the old grey-matter perhaps more than is comfortable. A week is a long time in politics. Twenty six years is a generation. What else has changed in that time?

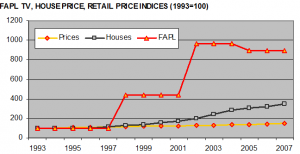

We witnessed average UK house prices rise from around £52k, when Manchester United started their successful campaign in 1992, to £182k when they won it again in 2007, according to Nationwide. Had house prices kept up with football revenues they would have averaged £466k in 2007. So the FAPL achieved something like 2.5 times faster growth than house price inflation in its first fourteen years.

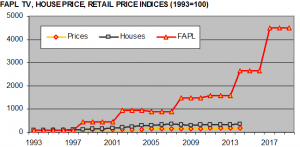

House prices subsequently fell and rebounded such that the average when Manchester City were crowned champions in 2014 was £186k. Had they kept up with football revenues in that time, they would have averaged nearly £1.4m in 2014 – growth a little over seven times faster than average house prices to now. Football has divorced itself from the rest of us in the process.

That all still feels fairly hazy, to me at least. We can make things a little easier and remove some of the mists of time and look at the here and now.

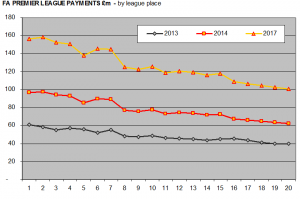

Four short years separate the champions of 2013 from the champions of 2017. Manchester United (quelle surprise?) earned a total of £60.8m from the FA while winning the Premier League in 2013. In 2014, Cardiff City finished 20th out of 20 and were paid £62.1m. The prize for being the worst team, one year later, is the same as the prize for being the best team the year before.

We have just experienced a quantum-leap in FAPL revenues that we struggle to mentally – let alone morally – process. Is it a freakish anomaly, something we can and will adjust to? Well, no, actually. It is something that is about to repeated in a little over 18 months. The winners in 2016 will make a little under £100m from the FA. The worst team in 2017 will earn a little over £100m, the best, a little under £160m, based on the 2014 income distribution.

Between 2013 and 2017 the average Premier League team will have an additional £78m each per year from the FA for Premier League participation. The top four, something like £96m each. To put that into houses again, it’s like the average house reaching £2.25 m rather than something around £200k in 2017.

Between 2013 and 2017 the average Premier League team will have an additional £78m each per year from the FA for Premier League participation. The top four, something like £96m each. To put that into houses again, it’s like the average house reaching £2.25 m rather than something around £200k in 2017.

The rest of this article is for Subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]