Zidane Clustering Theorem, from what I can tell (and while I like numbers, I’m no mathematician), is as follows:

How good a team is depends not on adding their quality ratings (out of 10) together (i.e. 8 + 6 + 9 and so on through all eleven players) but to instead multiply those figures. It is designed to show that teams full of very good players are better than those with a few superstars and a collection of also-rans making up the numbers (the ‘Zidane’ referring to the Real Madrid approach during the time of galácticos.)

How good a team is depends not on adding their quality ratings (out of 10) together (i.e. 8 + 6 + 9 and so on through all eleven players) but to instead multiply those figures. It is designed to show that teams full of very good players are better than those with a few superstars and a collection of also-rans making up the numbers (the ‘Zidane’ referring to the Real Madrid approach during the time of galácticos.)

So compare these two teams.

7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 = 77

10 + 8 + 6 + 9 + 4 + 5 + 8 + 7 + 5 + 6 + 9 = 77

But when multiplied, the first team, despite lacking the three outstanding (10,9 & 9) and two very good players (8 & 8), is far superior: 1,977,326,743 compared with 1,306,368,000. It works on the theory that the weakest link in a chain is just that: something that dramatically brings down the quality of the whole.

Such ideas are interesting, and fun, but are they conclusive of anything?

However, as they are interesting and fun, why not investigate?

Of course, this whole model is based on knowing exactly how good players are. But how do you assign a definitive numeric value out of ten to a player? And after all, a 10/10 player can have a 5/10 game, and a 6/10 player can play a blinding 9/10.

Of course, the most reliable barometer of effectiveness in football is consistency. Being world-class one week, Vauxhall Conference-class the next is not the hallmark of outstanding talent but the epitome of inconsistency. A regular and equal mix of 10/10 and 5/10 suggests that the player is, overall, 7 or 8 out of 10; a match-winner one week, AWOL the next – certainly no Zidane.

Then there are those who are described, by way of a compliment, as ‘7 every week’ players. This was often used on someone like Jamie Carragher, in his days as a full-back, before his emergence as an outstanding centre-half.

Every week he’d do a very good job, but rarely deviate from that steadiness due to the fact that he wasn’t really equipped for the overlapping part of the game. (Whereas someone like Roberto Carlos could look like 9/10 or a 2/10 player, often within the same game.)

And let’s face it, Steven Gerrard is as close to a 10/10 player as you’ll get, yet this season, for the first time in memory, his average marks per-game would have him nowhere near that level.

The theory cannot take into account tactics, form, or the balance of a side. But it does give an idea of just how good a team can be when everyone is playing to the best of his ability.

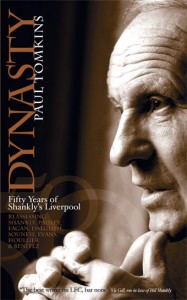

With all this in mind, I’ve calculated what I belief to be the players’ overall ratings, with the help of what a series of long-time Liverpool experts helped me devise for Dynasty.

With all this in mind, I’ve calculated what I belief to be the players’ overall ratings, with the help of what a series of long-time Liverpool experts helped me devise for Dynasty.

From this, I have created my own analysis of the Zidane Clustering Theorem, as applied to Liverpool FC teams from the Shankly era to the current day (see below).

What you make of it is entirely up to you (and I’m looking forward to interpretations from Subscribers.)

The rest of this post is for Subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]