By Paul Tomkins.

The title ‘Tomkins’ Law’ was recently assigned to my transfer theory by Dan Kennett, referring to my observation that only 40% of transfers succeed. (Naming a website after myself may seem vain enough as it is – although it was originally intended to be a solo blog – so I must make it clear that this term was coined by Dan.)

Years ago I’d guessed that only 50% succeeded, but my subsequent analysis of thousands of deals in the Premier League era showed that not even half the deals proved worth the money.

The figure of 40% came from ‘TPIC’, the Transfer Price Index Coefficient I devised a couple of years ago. The Transfer Price Index’s conversion of all Premier League transfer fees to a current value (CTPP) enables comparison across the decades; after all, £7m was a record-breaking transfer fee in the mid’-90s, whereas now it’s seen as fairly average; using TPI brings it into line with current big-money deals. (For more on TPI, which I created with Graeme Riley, see here.)

For TPIC (which excluded free transfers) I took all the current transfer prices – for instance, Jaap Stam cost United £38.9m in today’s money, Fabrizio Ravenelli set back Boro £35.8m – and assigned values to the number of games started, the percentage of games started, the CTPP paid, the CTPP sold for, as well as the percentage mark-up or loss; the result suggesting that the best-ever Premier League purchase was Arsenal securing Kolo Toure, who cost peanuts, played loads of games and was sold for a staggering 821 times what he cost.

I must at this point explain that if I altered the weightings, for example making pure profit more important than percentage mark-up, then Cristiano Ronaldo would be top; as it was, he ranks 2nd, but not as a player – only as a “deal”. As a player we can all agree that he was better than Toure, even though we’re comparing apples and oranges. After various tweaks, the final weightings seemed fair – to me at least.

With the latest set of inflation figures, Ronaldo’s sale fee surges to an incredible £124m. And since 2012, even though I haven’t updated the whole TPI database to TPIC, one signing definitely has leapt from flop to über-success: Gareth Bale’s increased starting rate, and his super-high fee meaning that he virtually matches Ronaldo and the elder Toure in the TPIC rankings.

(Out of curiosity I looked at Luis Suarez, and what a hypothetical £100m sale to Real Madrid would do for his TPIC ranking. The result is that he’d surge into the top five, meaning that three of the five best signings would either have been scouted or signed by Damien Comolli. That said, hopefully Suarez is going nowhere. And of course, Comolli also has the stain of Andy Carroll to his name.)

The point I made back in 2012 was that only around 40% of deals were in the black on the TPIC scale, out of a whopping 3,019 Premier League transfers between 1994 and 2012. Now, as I made clear at the time, this wasn’t a perfect reflection of whether or not a deal succeeded; all models are wrong, after all, but hopefully this still has some value in giving people an idea of the probability of success and failure.

The problem with TPIC can be seen in a signing like Dwight Yorke, who cost United £46.7m in today’s money, yet was sold for a measly £4.9m in the same money, on account of then being in his thirties. That’s almost 90% of his fee “lost”.

As part of Alex Ferguson’s late-‘90s four-man rotating strike force, before fading from the picture in his final two seasons, Yorke only started just over half of all possible league games. But was he flop? Certainly not. He scored the goals that won big trophies. (And as TPIC covers all playing positions, it can’t really reward goalscoring, because then, for example, Claude Makelele, whose job was never to get beyond the halfway line, ends up unfairly punished. Perhaps a rating system like that used by Who Scored? would work, but then such ideas don’t date back very far, so wouldn’t work on older deals.)

Despite being a success in the late ‘90s, in today’s money Yorke also represents a loss of over £40m, and while that’s something United could afford (not least through trophies and prize-money garnered), other clubs wouldn’t have been as able to take a risk on a player who was almost 27 for what, with TPI inflation, ranks as the 19th-biggest transfer of the past 22 years.

However, despite some anomalies, most of the signings at the bottom of the TPIC rankings can be understood as poor buys, just as most at the top worked wonders for their clubs, whether world-class talents like Ronaldo and Thierry Henry, or superb clubmen like Claus Lundekvam and Jussi Jaaskelainen; men who cost little and played hundreds of games, rarely missing out through injury, suspension and loss of form. Jaaskelainen was arguably as important for Bolton as Ronaldo was for United, and that is reflected in the rankings.

Many deals ended up as fairly neutral in TPIC: low purchase price, low percentage of games played, low sale fee. These ghost players clog up the mid-section of the list, joining and leaving clubs while barely being noticed. It has to be remembered that in the age of 25-man squads almost 60% of players will be sitting idle when any given match kicks off; and some of those will have been bought for emergencies that never arise. Players will rotate in and out, but often not ‘in’ enough to be seen as outright successes. Also, some regular starters will be homegrown, further narrowing the scope for signings to impress. The modern way means that a certain number of signings will inevitably make little impact.

The signings that do succeed spend more time in the XI, with the failures drifting to the fringes. But this isn’t a new phenomenon; I first mooted a “50%” rule when writing Dynasty, noticing that Bill Shankly, like Rafa Benítez, signed a roughly equal mix of duds and gems (whilst some other managers signed mostly duds). The only Liverpool manager to sign an exceptionally high number of successes was Bob Paisley, which perhaps partly explains why he won three European Cups.

Overall, approximately just 40% of all signings were in credit once put through the TPIC mincer. This is, to quote Dan Kennett, Tomkins’ Law. (Note: players who were still at their clubs were excluded from TPIC as none of their figures are set in stone, and they have no sale fee to include.)

Alternative

An alternative to ranking players based on fees and appearance data is to subjectively decide if a player did well following a transfer. This is also fraught with perils, as fans will always argue about such conclusions. That said, I wondered how such a method would compare with the 40% success rate seen in TPIC. Hopefully my judgements are valid enough to make it an interesting exercise, although I obviously know some players better than others and expect to have got at least one or two calls wrong.

To make it more manageable I decided to focus only on the top 100 most expensive players signed and sold since 1993 (after applying inflation), plus the 42 most expensive players still at the club at the time of writing (i.e. Wayne Rooney, Fernando Torres, Edin Dzeko, et al. The cheapest of the 42 ranked at £20m; all figures exclude players signed initially on loan. Also, there were 42 players out of the overall top 200 still at their clubs.)

I went through and declared each deal either a success, a failure or merely neutral.

It was easy to label Shevchenko – still the league’s most expensive signing (£80.5m in 2014 money) – a flop, just as it was easy to label Rio Ferdinand’s move to United a success, even though he cost “£73.3m” and left this summer on a free transfer. I tried not to take the fee into account, but of course it colours perceptions; if Shevchenko cost mere pennies then people would have been less scathing, and yet we can’t totally ignore what anyone cost when making a judgement call. Maybe the once-great Shevchenko wasn’t that bad, but it’s hard to argue a case for him.

Other players were more hit-and-miss, and difficult to label good or bad during their time at that particular club; perhaps they started brilliant and faded, or were slow-burners, or were simply hot and cold from one week to the next.

If I couldn’t decide, such as with Mesut Özil, I marked them down as neutral (in that he had bright moments in the season and anonymous periods too; he’s a top player, but as yet, not a top signing. Remember, this doesn’t take into account anything other than his football for Arsenal to date).

Out of the 142, I rated 40 as flops, 40 as neutral and 62 as successes. Based on my subjective judgements, then even at the expensive end of this transfer spectrum (remember, every player cost £20m or more in 2014 money) it seems that only 44% of deals can be said to be clearly worthwhile.

However, excluding players still at their clubs (such as Özil), it dropped to a precise 40% success rate (which was spooky, given the eponymous law). Of the 42 players still at their clubs I found I’d been more generous, ranking 52.4% as successes; but of course it’s far easier to conclusively judge a signing once they’ve been sold, and there’s time to reflect. While I was neutral on Özil, for instance, if he left this summer, especially for a cut-price fee, I think he’d be widely remembered as a flop. By contrast, Juan Mata, playing in a struggling side, did pretty well during half a season at United, and I labelled him a success on that limited sample size. None of this means that they won’t get better, or indeed worse, next season.

More Expensive?

What about players who cost more than £30m in today’s money? Coincidentally this more-or-less halved the list, from 142 to 69, and there was indeed a difference in the split.

Having paid over £30m (in today’s money), the success rate rises from 44% to 53.6%. But even spending such a fortune only bought success just over half the time; little better than a toss of a coin as to whether someone will succeed or fail when looking at the fee alone.

So, what about taking it a step further, and focusing on the deals that cost £40m+?

Again, the success rate rises, but only to 57.7%. Of the 26 players bought for such a fee, there’s no escaping Shevchenko, Mutu, Shaun Wright-Phillips and Fernando Torres moving to Chelsea, nor Michael Owen’s £47m holiday at Newcastle’s physio room. Then there’s the painful £44.5m that Liverpool buying Andy Carroll now equates to; a big lump if ever there was one.

Add Juan Sebastian Veron’s to United and Jose Antonio Reyes to Arsenal (although Reyes’ fee may be lower due to clauses not being met), and it makes for eight serious wastes of money out of 26 “£40m+” deals; or a ‘car-crash ranking’ of almost a third. (Of course, plenty of the aforementioned players won trophies, but that doesn’t mean they were key to those successes, or that it leaves them in credit over the course of the time at their club.)

Half of these 26 mega-deals were signed by Chelsea; 13 players costing over £40m TPI each. Four were fairly disastrous, seven (53.8%) were clear successes, and two were in between.

What’s interesting is that only one of these 26 was bought by Man City: Kun Aguero. (Carlos Tevez could perhaps be another, but there’s a lot of controversy surrounding his fee, reportedly ranged from £25m at the time to a whopping £47m subsequently; we took it as the first fee but are aware it could be the latter.) City do have a total of thirteen players out of the 69 to cost £30m or more in today’s money; Man United have fifteen, while Chelsea again lead the way, with twenty-two.

Liverpool, meanwhile, have just six: Carroll, Cissé, Heskey, Torres, Collymore and Aquilani. Only one of those – Torres – was an undeniable success. Also, bear in mind that the signings of Dean Saunders and Paul Stewart narrowly predate the TPIC years, and they too would be in that price bracket.

If these prices, with inflation added, seem unrealistically high, it’s worth noting what now constitutes a really expensive signing, with Gareth Bale almost touching £90m. If Bale is worth £90m, then Ronaldo has to be worth £124m. And with a much bigger TV deal in the Premier League, prices will probably rise again; they always have in the past. So it could be that £4m is the new £2m.

Lambert, No Butler

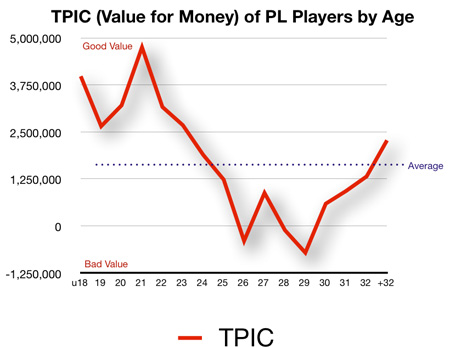

A couple of years ago I wrote about the value for money of a range of players using TPIC, splitting them down into 16 different age groups. The chart below highlights the results, which shows that 29 is the worst age to purchase a player; they’re not yet 30, so they can still command the fee of a twenty-something, yet as with buying a new car, they instantly depreciate the minute the contract is signed.

It’s not until the age of 32 – the age of Rickie Lambert – that it becomes more economical. By this stage the fee is negligible, but as seen with Gary McAllister in 2000, some older pros still have a couple of years left in them. Obviously quite a few of these 32+ deals are goalkeepers, who peak much later, but as long as the player remains hungry, and isn’t carrying various chronic injuries, then it’s worth a punt.

If there’s one thing TPIC cannot tell you it’s precisely who to sign. Every individual is different, as is every situation they are transferred into. What it will do is show you that mistakes are unavoidable, even if the bank is broken. Of the thirteen transfers that cost over £50m in today’s money, less than half – just 46% – worked out well.

NOTE TO SUBSCRIBERS: There is less than ONE WEEK remaining to preorder the new TTT book. Only a limited number will be printed, based on preorders by TTT subscribers; no physical copies will be available after or to anyone outside of the subscriber base.