By Paul Tomkins.

Okay, so have I got your attention?

Moaning about football fans on Twitter is often as pointless and interesting as moaning about the British weather. But every now and then I try to step outside of the oasis of calm that this website’s subscribers provide and see how the general LFC populous is feeling. I grow curious as to what the fans’ beefs are … and then discover that they’re less like beefs and more like steaming piles of rancid horseshit.

Some fans you can rationalise with. But plenty are just angry and ignorant, which is always a deadly combination. (See the rise of UKIP, and look up Dunning-Kruger for how this dangerous combination works.) It’s the kind of thing that makes people fly banners over stadia, although it has to be said that this seems to be a Man United tradition, so it may have been what the modern young person calls “banter”, and which I call being annoying little cunts.

Whether or not you use Twitter, with the plane flying over Anfield you got an idea of the mentality of many of its users; and whether they were classless Liverpool fans or childish Man United supporters, they conveniently used fewer than 140 characters on the banner.

This site is very different, of course. To paraphrase John Lydon, I am the anti-bantz.

Before the game on Saturday I chose to engage in a bit of ‘debate’ on Twitter, which careered past banter and into the depths of faecal matter scrawled on the walls of padded cells by drooling maniacs. I defended Rodgers’ record, and got abuse. Some of that abuse included praise of Rafa Benítez, who I happen to be a well-known fan of – so that was weird. The abuse also included criticism of Rafa Benítez, which I responded to by defending the Spaniard’s record too.

Many of these were from proponents of the appointment of Jurgen Klopp, and the kind to definitely not rate anyone who has a poor season – so don’t show them the current German league table, or their brains may explode. (Not that Klopp isn’t a great manager, as I think he is, but if you can fall to mid-table with one of the biggest Bundesliga clubs then maybe you’re also human).

As part of this great debate, someone blamed Rafa for the failure in 2007 to beat AC Milan (despite outplaying them that time), and you have to be a moron of a quite galactic scale to blame a manager for losing the final of an elite competition that the club hadn’t reached in 21 years before he pitched up, and when it was his second time in three seasons. They blamed him for throwing away the title in 2009, despite going closer than anyone else since 1990. I’ve heard all this crap before, for years now.

Equally, given that Liverpool hadn’t won 26 league games in a single season since the late ‘80s, and never scored 100 league goals in a top-flight campaign, you’d have to be a moron of an equally galactic scale to blame Rodgers for the Reds falling slightly short last season. If Liverpool had won five titles in a row, with a raft of expensive players, then yes, maybe the manager would have been to blame – but in this case it was the manager who oversaw a quite staggering improvement on the previous four seasons (which, in addition to his own debut campaign, were under three different managers).

If it was all down to Suarez – who, let’s not forget, hadn’t been prolific in England when Rodgers took charge – then Manchester United have to hand back the titles won with Critiano Ronaldo, and nothing Pep Guardiola did at Barcelona counts because he had Lionel Messi. This kind of logic is understandable to most five-year-olds. Benítez was only ever any good because of Gerrard, or then Torres, and so on.

Whilst I’m not convinced Rodgers is as good as people say he thinks he is (but managers do need a high opinion of themselves just to take on the role), the tacky protests, on Twitter and in the air, just makes me want to further rally behind him. Don’t get me wrong – I genuinely wouldn’t be unhappy if he was replaced with Klopp, but equally, I wouldn’t demand that he be sacked at all. The only manager I’ve done that with is Roy Hodgson, and his was a tenure with nothing but doom, gloom, dross and really bizarre statements – with no sign that he could handle expectations at a big club in a big league (he’d never finished as high as 2nd in one, for a start, despite his Blackburn and Liverpool sides being comparable financially to Rodgers’ last season, and I’m guessing his Inter Milan weren’t cheap either).

I’d expect Rodgers to have a better season in 2015/16, with everyone now clearly focused on what needs improving, but equally I’d be tempted to bring in Klopp simply to stop the tiresome bickering between Rodgers fans and Rafa fans, or the large sections that seem to hate them both. As someone who rates them both – I’m more of a fan of Benítez, but feel I have a handle on the task Rodgers faces – it’s utterly depressing. (I’d also be happy to see Rafa back in charge one day, if the circumstances are ever right – but as so many Liverpool fans still seem to hate him it could easily just take us back to his final season.)

Now, this has turned into another very long article – but it covers a whole host of the aspects involved in how clubs perform, with plenty that doesn’t relate purely to Liverpool FC (there’s lots about Arsenal, Southampton and Newcastle, for example). This is a whole shed-load of context – the kind that good newspapers don’t have the space for, and bad newspapers don’t care to acknowledge. It’s the kind of context the Twitter trolls will never understand, but with the nastiness about Rodgers on the rise, I feel it’s my duty to offer a forensic defence based on the situation.

Proper analysis

Now, I believe I’m an expert in certain areas of football analysis – a position I’ve achieved through years of research and writing. Equally, I’m the last person you want to ask about who is a good prospect in Serie A or the Romanian second division, or what it’s like to go to games home and away every week for 30 years, or the culture of the Kop in the 1970s – which is why I don’t write about those things, or claim to be an expert in them. I don’t watch every Premier League game (I lost interest once too many were being broadcast), and bar the play-offs I don’t really watch anything from the lower divisions anymore.

I played to a decent level as a semi-pro (and played in every position at that level bar centre-back and goalkeeper), held a season ticket at Anfield for several years, and I think I have a good “feel” for the game. But I can’t tell you all the pros and cons of every kind of formation, and the best way to counter them. I don’t understand tactical theory like this site’s Mihail Vladimirov or the esteemed Jonathan Wilson, or know about Liverpool’s 1912 team like the LFC History guys (aided by this site’s Graeme Riley), or have the contacts and ear-to-the-ground of a Tony Barrett or James Pearce. There’s a lot I know about football, as someone whose skill is observing and finding patterns, but with age and wisdom comes the realisation that you can only ever scratch the surface.

However, I’m possibly as good as anyone on the probabilities of the transfer market, and, with the work undertaken with Graeme Riley, I can show the strength of the correlation between transfer spending and league position in the modern era; even clearly pointing out how it has changed over time – particularly over the last 12 years. I feel that I’ve actually proved this stuff, and at times feel like a scientist who has presented evidence of global warming only to be counteracted by people saying, in the depths of winter, “but it’s snowing where I live, so the planet can’t be getting hotter, you douchebag”.

Those brave enough to have taken the time to properly read my writings on the subject often say that my conclusions are depressing; my take is that it’s a relief to be free of the unrealistic expectations that bring distress on an almost annual basis. I believe that I enjoyed last season more than a lot of Liverpool fans because I was convinced that the quality and experience wasn’t quite there, and that shortcoming was nobody’s fault; and when it fell apart at the end, I thought about how brilliant the ride had been, and that taking the title down to the wire was remarkable given where the team was at the end of the previous campaign, and that it cost so little compared with the big guns.

Some of what I will say will be a case of repeating myself, although I’m always looking to try to better sum up my arguments, whilst adding new angles and nuances along the way. (Although hopefully this is my definitive piece on the subject for now, and I can get on with other stuff.) Sometimes I’m driven to repeat myself because the same dumb arguments are lobbed back at me all the time, but of course, my argument is too complex to explain on Twitter, and yet the people who should be reading it don’t have the concentration span to get past the first paragraph. Perhaps, slowly but surely, I will make a few new people understand how it all works each time I explain it, and as I find new examples. And hopefully it will reach those who aren’t wilfully ignorant but who just haven’t thought about it in any depth.

For now, I don’t think I can make my points any better than I have in this piece, not least because it counters pretty much all the half-arsed (and half-decent) responses I tend to get.

The model isn’t perfect, but it’s pretty damn good

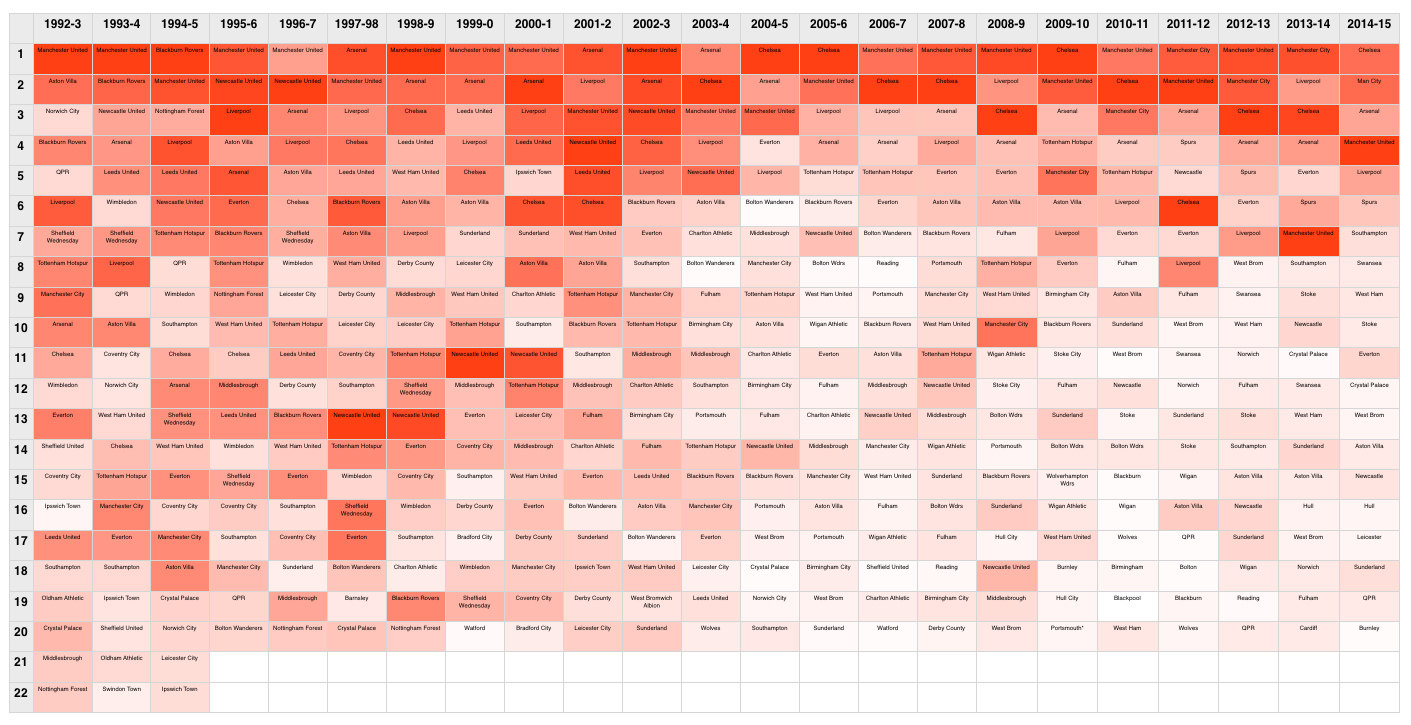

Unusual things can happen in football; but with Chelsea confirmed as champions once again, it hasn’t happened in decades regarding the top spot. Come May, most of what you see is predictable.

The TPI model that I use to predict league positions said that the potential champions would be from the usual über-rich trio of Chelsea, Manchester City and Manchester United. You might say “well, der! – these are the best three teams”. Well, precisely. This is because they cost tons more than everyone else. You may think they’re just coincidentally the best teams. I can prove that they are the most expensive by far, and therefore, there’s nothing coincidental about it.

The model also has Liverpool finishing 5th, and Spurs 6th. There are variations from year to year further down the table, where the financial differences are far less pronounced, but for 11 seasons in a row the title-winner has come from the Rich Three, as predicted, and no-one unexpected has broken into the top four since Everton in 2005 – perhaps David Moyes only really impressive achievement as a manager.

(As an aside, I warned in 2010, in the inaugural edition of the Blizzard, that the Premier League years were full of overachievers up to a certain point in the table who play “solid”, but often uninspiring football. These are great for clubs wishing to get into the top half of the table, and maybe to become outsiders for what was the UEFA Cup, but often don’t have the personality and skill sets to handle the pressure of a massive club. You may occasionally get an exception to the rule, but Moyes at United, like Hodgson at Liverpool, looked like a deer caught in the headlights – poor in the league, awful in the cups. These types win the LMA Manager of the Year as plucky underdogs, but that doesn’t make them cut out for winning 70% of their matches with better players. Big money wins you things, but you usually need a big character to manage it.)

Only once since 2005 has a relatively cheap side broken into the top six – and they also happen to be the same club who are the only ones since 2003 to get relegated with a fairly expensive side: Newcastle, relegated in 2009 with a relatively costly £93m £XI (so basically what Spurs cost now), and finishing 5th in the Premier League in 2012 with an £XI of £51m.

Perhaps as a kind of law of radical overachieving, the drop the next season can be very severe as reality sets in: Newcastle fell to 16th in 2013, as the pressure to do better rises. But average those two seasons together and you get a 10th-placed finish, which matches their TPI expectations over those two seasons.

Equally, average all of Rodgers Liverpool seasons together and they exactly match the TPI expectations, which is precisely the same as what happened with Rafa Benítez (who had the benefit of Champions League cachet, but the drawback of too many games for a limited squad).

Over time, very few people end up beating the odds; the times when they do so are usually part of an up-and-down swing. Everything, it seems, regresses towards the mean when it comes to expenditure and league position. It just has to be measured as team costs (£XI) and not as misleading gross or net spends, or what happens in a single transfer window, which is meaningless without the context of how much the team already cost, or what players they might be selling to finance it.

(Note: the £XI is the average cost of all 38 of a club’s XIs in a season, with transfer prices converted to current-day money.)

One thing that fans expect is constant upward projection; positive momentum. But I feel that a good way to explain it is that every club’s fortunes ebbs and flows. While no manager can now afford the first six seasons Alex Ferguson had, they fluctuated wildly. Big clubs don’t tend to drop outside the top seven these days, as noted, let alone finish in the bottom half; but even when he was winning league titles there were still seasons when United appeared to be regressing. They didn’t sack Ferguson or sell all the players. In 2006 there were articles writing off Ferguson’s squad, including players like Ronaldo, and the manager himself; they then won the title in the next three seasons. In the last four seasons Manchester City have twice been relatively crap after winning the title, with much the same squad. Under Rafa Benítez, Liverpool were almost alternatively good in Europe or in the league. Arsenal are often lurching from a perceived crisis under Arsene Wenger to finally challenging, often within the same season, before they finish in much the same position. Football is very rarely about clear, unbroken improvement. You will probably spend at least half the time thinking that your team is going backwards, but that doesn’t mean it’s not going to start going forwards again soon. Or that, when it’s going forwards, there won’t be a stumble and fall on the horizon.

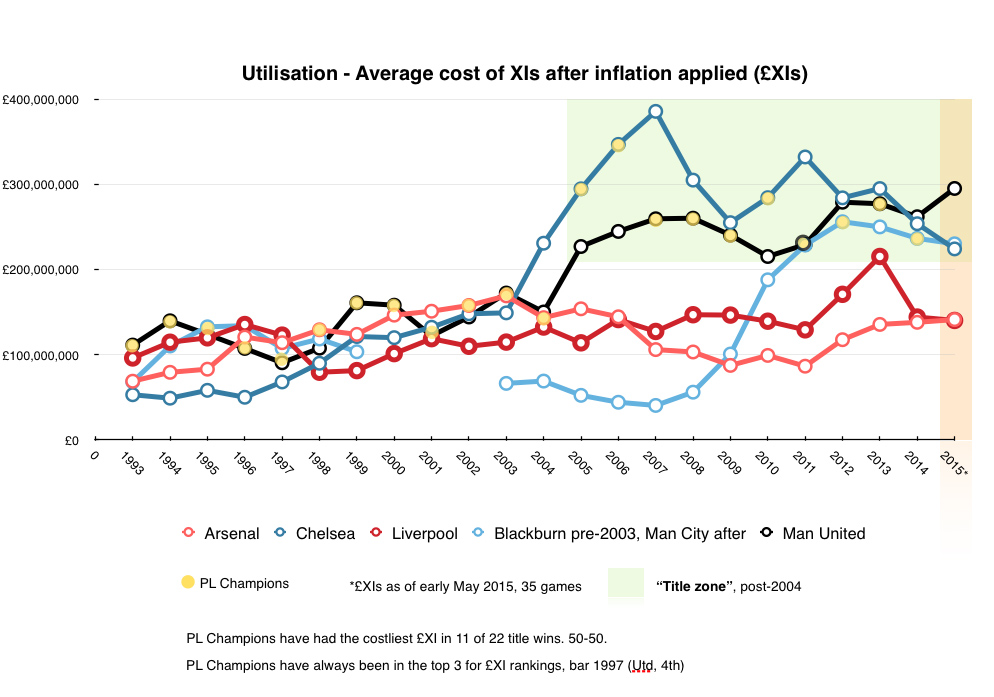

Before moving on, reminder of the graph that proves the might of the Rich Three, and how they are the only clubs in the Title Zone. This has been updated today now that Chelsea are confirmed champions.

The Rich Three can still have bad league seasons, and fall out of the top four, but never, it seems, finish lower than 7th. Inexpensive teams can have good league seasons, but almost never finish above 7th. All season long I’ve said that Southampton will falter. They’ve done amazingly well, but the first half of a season, when they were top three, can be about great management and a good side that works as a unit and is high on confidence; but the more games that are played the closer the results follow the TPI model. And by the end a team’s £XI tends to correlate closely with finishing position.

After all, Southampton’s £XI ranks 9th, so 7th is a fine achievement – slightly better than par – but plenty of inexpensive teams have peaked at 7th; none ever seem to go above that. Southampton lost a lot of players last summer, but they reinvested wisely in what was admittedly a tough task: getting so many new players in at once. Last season they finished 8th with the 14th-ranking £XI, and are set to finish 7th with the 9th-ranking £XI. Selling actually allowed them to increase the cost of their team (partly because Liverpool overpaid while they bought from better markets). Perhaps crucially, everyone expected them to be relegated, even though they had the 9th-most expensive team. The pressure was off, in a strange way.

Southampton’s £XI is actually £10m greater than Newcastle’s this season, but because Newcastle challenged for the title in the mid-‘90s (and have a big stadium) there seems to be a raised expectation in the north-east, where I imagine that they usually expect to finish above Southampton. Perhaps it lingers from the days of Keegan, and this is worth remembering: in 1995/96 they had the 4th-costliest £XI, finishing 2nd, and in 1996/97 they actually ranked 1st – by some distance – but finished 2nd. (Average TPI ranking over those two seasons: 2.5. Average finishing position over those two seasons: 2nd.)

When they got back into the top four in 2001/02 under Bobby Robson they ranked 2nd financially, which even I found surprising, and when they finished 3rd a season later they ranked 3rd. When they finished 5th in 2004, they again ranked way up in 2nd – but this is when the new era of Chelsea mega-wealth was about to go into overdrive, and the bigger ‘90s clubs, bar Man United, soon started to fall behind (Newcastle, Arsenal and Liverpool were all soon dwarfed). A year later Newcastle had fallen to 5th in the £XI rankings, and to 14th in the league table – Robson had gone, and the side were managed by Graeme Souness.

In 2008 and 2009 they were ranking 6th – still putting them down as should-be European contenders. However, in the past four seasons Newcastle have averaged approximately 10th in terms of the average cost of their line-ups, and whether or not that’s because the owner has been negligent is not for me to say (as I don’t know). What I will say is that when Alan Pardew took them to 5th in 2012 they were, as noted earlier, the cheapest side to get that high in a decade. This is why I thought Pardew was doing a good job, especially given the fans’ contempt this season, albeit his tenure moved with the ebb and flow that most clubs experience. (Only Arsenal seem to be constant in their finishing position, year after year. Wenger keeps getting them into the Champions League, but the Champions League arguably stops them doing better domestically.)

The Newcastle fans wanted Pardew replaced with a proper manager – but they are owned by someone who, in 2008/09, appointed Kevin Keegan, Chris Hughton, Joe Kinnear and Alan Shearer en route to taking an expensive side down. Therefore, in disliking Pardew because he was an “Ashley man”, they missed the point that Ashley was only going to appoint another Ashley man – and that it might be someone pretty rubbish. But that’s another story, and I have some sympathy with the Geordies – and I can’t pretend to know the full ins and outs of their disgruntlement.

What’s interesting is that Southampton were the definition of a “selling club” last summer – more so than Newcastle have ever been under Mike Ashley, even if the Saints didn’t appear to sell their soul in the process. Southampton were fed upon by bigger clubs, just as Newcastle were when Yohan Cabaye moved to France. It can become virtually impossible to keep players against their will when more glamorous clubs come calling. Perhaps the difference is that Southampton immediately reinvested the fees, whereas Newcastle didn’t.

But even as brilliantly as Southampton have done, they haven’t broken through the TPI glass ceiling of 7th place – in the last decade Fulham, Blackburn and Bolton have finished 7th with very inexpensive squads, but unless Southampton leapfrog one of Liverpool or Spurs, it’s going to be ten years with only one relatively cheap side (Pardew’s Newcastle) finishing in the top six. So the model tells you that a “cheap” team can finish 7th, but they almost never push beyond that.

The longer the season wears on the more it becomes about the squad. Players get injured, and those who play every week start to get jaded – while cup runs, if they occur, can add to fixture build-up. Money is required to create and maintain a big squad, unless there’s an exceptional youth policy that provides top-quality replacements – but this is very rare indeed. Almost always, money counts.

Below is an updated version of the graphic that first appeared in Pay As You Play five years ago. It shows the costliest side in each given season as the deepest shade of red, with every other side reflected as a percentage of that (so if it cost half it will be a 50% shade of red). The table has the clubs in their finishing positions, and you can see how the money is now concentrated in the top seven, whereas up to the arrival of Roman Abramovich it was more evenly spread around. The rich are getting richer. Liverpool in 2008/09 and 2013/14 are two of the (relatively) cheapest sides to finish in the top two in the entire Premier League era.

Now, people insist that you can beat these odds. And, for brief periods, some clubs appear to be able to do so – just as Newcastle did by selling and buying well prior to 2011/12, and Southampton have in 2014/15. But no one outside of the Rich Three has broken the odds and won the title in 11 years. And England is unique as it doesn’t have a Rich One (Germany, Italy) or a Rich Two (Spain). It has three powerhouses. (See the Appendix for more on Atletico, Dortmund, et al, which is a whole other story.)

What happens, virtually all of the time, is that a lack of money exposes a problem with the squad. And that problem ends up being blamed on the manager.

Think about it. It’s true, isn’t it?

Now, the manager in question may have his faults; indeed, he will have his faults, as he’s a human being. And if he is responsible for buying the players – and not all are – he will be blamed for not buying the correct players – even though all managers and Directors of Football buy the wrong players, even if they are apparently buying the right players (because 50-60% of all transfers fail to be clearly successful).

You get what you pay for

People understand the concept of “you get what you pay for” with individual players – even if you don’t get what you pay for as often as you think, as I’ve proved many times – but they often don’t accept the concept that if you add up everything you’ve paid, and it’s not enough to take you to the level your fans aspire to, you’ll probably fall short. Somehow the manager gets the blame.

The more money you spend on the squad, the greater the chance of having a better XI and better back-ups, and, crucially, of being able to have some expensive flops who offer nothing. The less money you have the tougher it is when you make the kind of mistakes everyone makes in the transfer market.

Think about it. Arsenal and Liverpool are always supposedly one or two players short of challenging (maybe three, depending on the pundit). But the average cost of their £XIs is always at least £80m short of the Rich Three over the course of a season.

Now, put two £30m players into their XIs, plus one for £20m, and they’ll be closer. Easy!

But if they could afford to be doing that, in terms of transfer fees and wages, as well as convincing the players to join them, they would. And also, the law of transfer averages, which I’ve pointed out many times, means that it’s virtually impossible that all three signings will live up to expectations, and seriously unlikely that all three would do so in their first season. You often have to spend twice as much as you want to get the number of successful signings craved.

So, for Arsenal and Liverpool to add those three players without being given a ton of gold bullion (that FFP then turns a blind eye to), they’ll probably have to sell some good players first. But hey, you say – why not sell the bad players? Hmm, I say – who is going to pay good money for your deadwood? Or offer a good fee for your unsung heroes?

Now, those three fairly expensive players arrive. The likelihood is that one settles quickly and is brilliant; one takes to his second season to settle; and the third fails altogether, due to injury, homesickness, poor form, or whatever. So it’s two years before you’re getting just 2/3rd of what you paid for in terms of performances. If you’re lucky, within two years you’re getting £60m benefit from £80m spent, but overall, on all transfers, you’re probably going to get £40m benefit from £80m spent.

In terms of getting what you pay for, you may get 50-60% benefit from your mega-buys, but as I’ve noted before, currently only five of the 11 most expensive Premier League signings (after inflation) can be considered clear successes. You increase your chances of getting a top player by paying more, but top players like Shevchenko, Veron, Torres (at Chelsea) and Di Maria (to date) have proved that even the world’s elite can be utter duds. Plenty of no-brainers turn out to be awful, or merely average.

And every club only ever gets 40-60% of their expenditure into their XIs over 38 games. This happens every season. On average in 2014/15, a whopping 53% of the money all clubs spent on their squads (including only those who have made at least one league appearance) ended up on the bench or in the stands.

The current top five have a “wastage” of between 46% and 55%, with Liverpool’s at 50%. That means that Liverpool’s £XI is £141m and their squad cost, after inflation, is £281m. United’s wastage is slightly lower, at 47%, but the cost of all players they’ve used in the league is a whopping £557m TPI. Now, part of this “wastage” may be down to injury, suspensions or all kind of things. But it shows that no matter what a club spends, at least 40% of that spending will not be in the starting XI, and it may be as high as 60% or more. And it’s the same further down the table: Burnley are at 49%, for example, and QPR at 60%, for the amount of spending in relation to players who don’t feature.

Odds

People think you can improve your transfer odds by going back in time and just buying players who have gone on to do well elsewhere. Even if these were obvious signings, it doesn’t mean they would have succeeded at your club, in this given season.

When it comes to assessing these things you can’t then say “If Liverpool had just bought Remy instead of Balotelli or Lambert, things would be so much better”. Because, had he signed for Liverpool, Remy may have broken down with injury in the first training session – cue a million fans going mental for signing a player with medical issues – or myriad other things. He may have been great, and he may have been rubbish. He may have been great, but also broken Emre Can’s leg in training, and then we’d be wondering why only Remy was looking a hit from the summer’s business, and why we spent £10m on a young German who is never fit.

We all say certain players should never have been signed, but then we’ve all been shocked by players who should never have been signed who went on to be excellent. We’ve all said a certain player will definitely succeed at a certain club, only for him to then fail. We can’t just keep the ones we get right and pretend the ones we got wrong didn’t happen.

Spread thick or thin?

If you spend £300m on ten £30m players, you might get five or six superb first-teamers, but you’re almost certainly guaranteed some flops. If you spend £100m on ten £10m players you might get three or four successes, and maybe an extra flop or two. Yes, it all depends on the individuals in question, but no one has worked out a way to never sign duds.

However, if you have a small squad and spend £50m apiece on two players, it might be great; but if one flops, as the law of averages suggests, and the other gets injured, as can happen, you’re screwed. If you spend the £100m on ten players you might end up with ten scraps of deadwood, though it’s unlikely. However, the odds suggest that you’ll get at least a gem or two (see Can, Emre). But – and this is the key to the whole damn thing – no matter how you slice it – two £50m players or ten £10m players – if your squad still costs only half that of your rivals, you’re probably going to finish below them. You cut the cake thick or you cut the cake thin, you still won’t get as much as someone with two cakes.

So if your £XI costs below £150m each season, and the Rich Three remain at £220m-£295m, your team is still miles short. You are as far from the title as teams like Southampton are from the Champions League; it looks possible, but really, it isn’t.

Go back to the earlier example. You’ve added the three aforementioned mythical players but it’s taken two years to get two of them to purr; but in those two years all kinds of stuff has happened: you’ve also seen your ageing stalwart decline and eventually retire, and one or two of your best talents have been whisked off to Spain because, in all reality, you can’t force them to stay against their will when Barcelona or Real Madrid come calling.

If you’re lucky you get a big fee for one of them, but another will leave either on a Bosman or as an agent-enforced just-one-year-to-go half-price sale (because he’s threatening to do a Bosman). Another of your best players breaks his leg, or snaps his hamstring, so he’s out for the season. You’ve also bought some other, cheaper players, and some of those will do surprisingly well and others will become deadwood. Some youth players will graduate, although maybe none will be outstanding.

If you can’t afford to pay the highest wages (and FFP limits spending in relation to a club’s turnover) then you can’t afford to keep all your best players and buy only top-class new ones. Somewhere the maths breaks down. You gain in that period of time, whilst simultaneously losing.

What tends to happen is that if you’ve got a mega-squad you can lose a player for three games at a key stage of the season and prevail; if you have a smaller squad, which costs much less, you bring in Iago Aspas and you fall short. If you don’t fall short then, then you fall short at some other point.

On a lower budget, the law of averages suggests you don’t have seven international-class replacements on the bench, and six more who can’t even get into the match-day squad. You can stupidly blame the manager and players for bottling it, or bemoan the tactics (or rotation/lack of rotation), but it’s ultimately moaning that the blanket doesn’t cover your toes when you pull it up – when, if you pushed it down, it’d leave your shoulders cold. All the while your rivals can afford a bigger blanket, that covers more areas (as they eat their two cakes in bed).

And if these clubs change the manager the shortcomings in the squad will expose him too. He’ll be better at tactics but too conservative for your tastes; or he’ll be a better motivator but not as clever; or he’ll like pretty football but be too soft; or he’ll give you midfield enforcers but you’ll think he’s denying you a cutting edge. He’s never going to look like Pep Guardiola deploying Bayern Munich’s players. He’ll never be the best manager with an impeccable squad.

Few managers are perfect, and even Jose Mourinho last season, upon seeing that he had an expensive squad that wasn’t ideal, gave up the ghost and accepted 3rd place and no trophies. Now, Chelsea bought brilliantly in the summer, but when he was hamstrung he wasn’t quite so good, was he? He inherited a ton of top players in 2013, some of whom he’d signed or coached first time around (such as Petr Cech, Frank Lampard and John Terry), but he couldn’t make a top side out them until he’d brought in two £30m players in 2014 on massive wages. The loss to injury of just one player – Costa – almost cost them, but in fairness they dug in and, without much of a challenge from anyone else to put them under serious pressure, they saw it through.

My argument is that, since 2004, Arsenal and Liverpool have been financially hamstrung compared with the Rich Two (up to 2009)/Rich Three (once City joined them). They are always caught in compromises, like Mourinho last season.

Get a new manager and you’ll probably just find something else to moan about, and whatever you moan about won’t necessarily be true anyway: Benítez was “too negative”, for example, but in 2009 his team were the Premier League’s top scorers, and his Chelsea also scored loads (while his Napoli team score a lot too). Rodgers “can’t coach a defence”, and yet Swansea had a load of clean sheets under him in their debut Premier League season (13 I think), and his Liverpool side have kept clean sheets in seven of the last eight league away games, which is unheard of. These managers have weaknesses, of course, but the squad cost limits them – there’s always the time when they look to the bench and it’s Aspas or El Zhar. (And it’s not necessarily the manager’s fault there’s an Aspas or an El Zhar – just the difficulty in building a big squad on a limited budget, where holes will always exist, because bad transfers happen to everyone.)

Cups with a limited squad

In Rafa Benítez’s case I believe he takes his teams on so many extended cup runs it makes the league form harder to keep constant – because he always ends up with rescheduled fixtures and games crammed in towards the end of the season; and even the biggest squads can struggle there (and only at Chelsea has he had a big squad). This leads us into another area, in that silverware is important – but the cups (and particularly the Europa League) damage league form.

If playing games every three or four days increases the likelihood of injuries (and the famed AC Milan lab said it did), then to play 60-65 games a season means more injuries, which means you need a bigger squad to cope. But if you have a limited budget, you almost certainly cannot add both quantity and quality. You add quantity, and it’s spread too thin; you add quality and you don’t have enough fit and able bodies and risk losing all of your investment in one or two bad injuries. (Youth graduates are one answer, but they are often inconsistent, and that inconsistency then becomes the gaping hole in the squad.)

My sense is that even for an outside chance to win the title, Liverpool have to focus solely on the league, and use all of the cups for squad players and youth graduates, with Rodgers (or Klopp, Benítez or whoever) not even travelling with the team to cup games, but staying at Melwood to drill the senior side for the league fixture. But I don’t think any managers are ever keen on that, because they need trophies for their CVs – and some fans will want silverware and league success, because they think it’s 1986. And no one who pays to travel to watch games wants to see a shadow squad put out. It’s just that it might be for the greater good.

Managers want to win trophies, to instil a winning mentality. And the ‘problem’ is, when you finally get into the Champions League you naturally have to take it seriously – and then, of course, your league form can suffer, and you fall down the league table, perhaps out of the top four. The answer? Bigger, more expensive squads. Something which FSG can’t afford, and in Liverpool’s case, FFP won’t allow. The owners had a brief go, as could be seen in the spending of 2011 (Liverpool almost went into the Title Zone), but that was their first year in charge, and the only year when they could spend big and not fall foul of FFP. Since then it’s been far more complicated, with some expensive duds, some supposed duds who came good, and Luis Suarez, who came and then went.

Benítez and Rodgers – hamstrung managers

My opinion is that at Liverpool, neither Rodgers nor Benítez had/has a squad that costs anything remotely close to those of the richer clubs (this part is fact, to paraphrase a certain Spaniard, not opinion). And therefore, holes in the squad were/are inevitable; just as those with less money than Liverpool, like Everton, will mostly have either more holes in their squad (enough to fill the Royal Albert Hall), or weaker best XIs. Sometimes these holes will be exposed and other times they’ll be covered up, but they’re always there, waiting for November or February or May, when it becomes obvious. Unless you are a genius in the transfer market, who can beat the odds in a way that no one seems able to do over a long period of time, and/or are bringing through a crop of amazing kids, the holes are never far away.

Being rich doesn’t mean you’ll be successful, but being successful in the Premier League, beyond certain glass ceilings, happens only when you’re rich.

At times, the richer clubs will screw up and appoint a bad manager or buy the wrong players, and you may overtake them. But it’s usually only briefly; before long they change the manager and spend tons of money again. The poor can beat the richer in individual games, as we all know – and occasionally do better in seasons as a whole – but never if the rich are at their best. Depending on the wealth gap, the richer will win (or finish higher) seven, eight or nine out of 10 times.

Sometimes Everton will finish above Liverpool, but mostly Liverpool will finish above Everton. Sometimes Liverpool will finish above Chelsea, but mostly Chelsea will finish above Liverpool. And as I’ve been stating for a long time now, if Liverpool are only likely to finish above Chelsea occasionally, and United occasionally, and City occasionally, then what are the chances of finishing above all three at once? The only chance, of course, is if all three have bad or below-par seasons at the same time. And the chances of that are remote; it hasn’t happened so far.

What are the chances of a team that cost £140m finishing above three teams that cost £220m-£300m, given that at least one of those expensive teams will almost certainly have a good season?

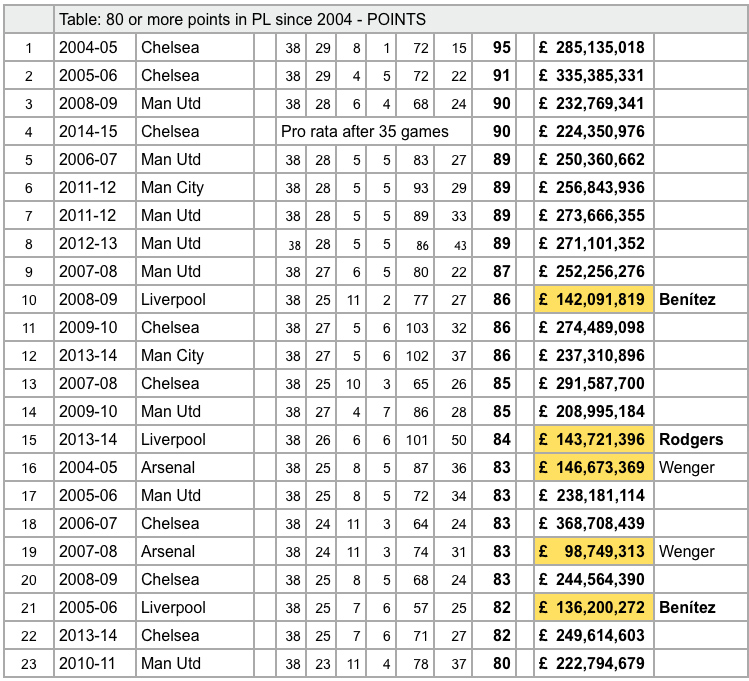

And how often does a team costing £140m (all of these figures are in 2014 money ©TPI) finish with enough points to even stand a chance? Without including Chelsea, who are on par for 90 this season but could still hit 92, the title-winners have averaged approximately 89 points in the past decade. In the decade before it was 81. How does a non Rich Three team hit 90 points?

But for now let’s look at just those who reach ‘only’ 80 points.

Since 2004 – when Chelsea first mixed money with Mourinho – 23 “teams” have finished with 80 or more points: Chelsea and Manchester United tied on eight times each, with Liverpool (surprisingly) third – having achieved it three times, while both Arsenal and Man City have achieved it twice. (Arsenal are currently on par for 77 points based on points-per-game, but could theoretically hit 82 with three wins; while Manchester City’s maximum possible is now 79, so they can’t reach the magic mark.)

Hitting 80 points is one thing; hitting 10% more than that something else. The top nine points-scoring sides since 2004 – ranging from 95 down to 87 – have all cost in excess of 220m, with the average at £262m.

Only one single time since 2004 has a team costing less than £224m finished with more than 84 points: Benítez’s Liverpool, who rank 10th in that time with 86 points, achieved with an £XI of just £142m: only two-thirds of what the nine above it, and the four directly below it, cost. (And people tell me he wasn’t very good in the league.)

So that’s just one of the top-14 points-scoring teams since 2004 (Benítez’s from 2009) costing what, for that kind of achievement, is pittance. Everyone else has cost north of £224m to hit the 86-point mark, with the peak £XI being £335m of Chelsea’s 2005/06 vintage.

What’s interesting is that in 15th place is Rodgers’ Liverpool, with 84 points, costing £143m – virtually identical to Benítez’s team that went two points better, but didn’t take the title right up until the last day (but they were up against the United of Ferguson, Ronaldo, Rooney, Tevez, Berbatov and co.). And the 16th-highest points scorer (since his Invincibles of 2004) is Wenger’s 83 of 2005 and which cost … £146m. All very similar.

In today’s money, the £XIs of Arsenal and Liverpool dating back to 1992 have never been higher than £169.7m. Liverpool and Arsenal average 20 league wins a season, and 70 points. Since 2003 they’ve averaged 21 wins a season, and 71.6 points.

What’s interesting is that since 2011, when combined, Arsenal and Liverpool have had an £XI that averages out at £142m. This season, Arsenal’s £XI is … £142m, and Liverpool’s is £141m. When Rafa Benítez’s Reds finished 2nd in 2009, the £XI was – remember? – £142m. Increase that by 50% and you still don’t get what the cheapest Rich Three side amounts to right now.

People talk about Liverpool having spent £770m in the Premier League era, but it doesn’t contain the context of how and why it was spent, and it doesn’t change that fact that Liverpool’s squad and £XI – at least since the ‘90s – has always been dwarfed by other clubs. Gross spend arguments are dumb; net spend arguments are flawed, but better – and team/squad cost arguments (as shown in our TPI work) are infinitely better than either when it comes to predicting where a team will finish.

What Benítez achieved in 2009 was incredible in relation to the budget – finishing 2nd with a team costing £142m, behind only United, whose average cost was £232m that season, and ahead of Chelsea, whose was £245m.

However, what Rodgers achieved last season was comparable. Manchester City cost £237m last season, and Chelsea, with Mourinho as manager, cost £250m. (United cost £257m; this year they average at £295m.)

This is why I defended Benítez at the time, and why I defend Rodgers now. I don’t just make this shit up – it’s all documented going back years (to 2010 in the book Pay As You Play) in terms of how effective the £XI is at determining league position. The correlations are clear to see, and the process can be seen from the Introduction written five years ago.

(It works out very similar to wage bill analysis, but this is the data we happen to own and use. We also find that the squad cost, once inflation is applied, closely matches wage bill analysis, but the benefit of £XI is that if a club’s expensive players all end up injured it will be reflected in the total – whereas wages stay the same no matter who is fit. Like any model it’s not perfect, but on average most clubs tend to finish within two places of their £XI ranking – see Southampton for the earlier example. There is far more variation in finishing position in relation to £XIs lower down the table, but everyone’s finances are more closely clustered: the team that ranks 13th may be only 10% richer than the team that ranks 14th, whereas the difference between 3rd and 4th is a drop of 50%. Equally, the Rich Three have vaguely similar finances, so the order in which they finish isn’t as clear-cut as the fact that at least one of the trio will be champions.)

The main change since that book, and since Benítez’s time at Liverpool, is the emergence of Manchester City. They pushed Liverpool from the 3rd- or 4th-ranked financial power into 5th, and squeezed the Reds out of the virtuous circle that rewards the top four.

Add two semi-finals and Liverpool have had a pretty decent season. The problem is that it hasn’t looked that way when watching the matches. Performances have been very poor for much of the season (almost unwatchable at times), with no strikers worthy of the name. And yet, even without a decent fit striker, and with an ageing talisman, and with a young side, and without a certain world-class Uruguayan, Liverpool are hitting ‘par’. That tells me that, for all his faults, Rodgers isn’t doing as badly as the critics suggest.

It’s up to other people to decide if someone else can do much better, and whether this is indeed just part of the ebb and flow of football.

(Edit: just to add here, I don’t want to kill all hope, which is what some people seem to think I’m doing. But Liverpool’s best seasons/teams since the glory days were in 1996, 2001, 2005, 2009 and 2014 – or roughly every five years. Maybe that’s our success-orbit now: Fowler, McManaman and Collymore in 1996; the treble of 2001; Istanbul; the excellent 2008/09 side with Torres, Gerrard, Alonso, et al; and last season, with Suarez and Sturridge. While this isn’t a set five-year pattern, I’m using it to show how rarely we feel totally excited by our side, but also, that these moments of joy and pride do still come around. The key, for me, is that these are now rare treats. But please, if you’re in the ground then stay hopeful and make a noise – however, don’t fall quiet if we’re not 2-0 up against a certain side because you think we should be winning the title, or think that the manager must be changed if we have a tricky spell. Hopefully FFP will level the playing field again, and make the sport more of a sport, and less of a case of financial doping; but again, don’t hold your breath.)

Appendix – Additional Points

TPI vs Finishing Position

That everyone eventually evens out to their financial level is a fact from our TPI work, based on the past 10 years, and the top 10 positions in the Premier League; i.e. the average finishing position for the richest club each season is 1st, the average finishing position for the 2nd-richest club each season is 2nd, and so on, without fail, down to 10th. This doesn’t mean that the 2nd-richest club in any given season will always finish 2nd – it means that over ten years they might finish 3rd, 1st, 2nd, 2nd, 3rd, 5th, 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 1st. And just to be clear, the second richest team may be Manchester United one season and Manchester City another, then United again, or Chelsea, and so on.

Poor teams can beat rich teams on any given day. But richer teams win more often, and poor teams rarely finish above rich ones; if they do it’s because the rich team has under-performed, and left the chance there.

Atletico, etc.

People keep pointing out the brilliance of Atletico Madrid to me, and whilst true, I keep pointing out the difference: they are the 3rd-richest club in Spain, where four teams get Champions League revenue; Liverpool are the 5th-richest club in England, where, once again, only four can thrive.

Atletico had an amazing season last year, and Simeone is almost certainly a world-class manager. But they also needed both Barcelona and Real Madrid to get much lower points totals than they averaged in the previous five years to stand a chance (a drop of around 10%, which is almost ten points; Barcelona are currently on course to get 94, closer to their recent average of 96!). Atletico jumped from 3rd-ranked to finish 1st in 2014/15; last season Liverpool jumped from 5th-ranked to 2nd. This season Atletico have fallen from 1st to 3rd, back to par; this season Liverpool have fallen from 2nd to 5th, back to par. No one is calling Simeone an idiot, and Rodgers was two or three points away from a genuinely world-class achievement last season. Yes, you don’t get anything for being nearly-men, but Liverpool won a fairly incredible 26 games last season, and it turned out they needed to win 27.

In Germany, Dortmund achieved a hell of a lot under Jürgen Klopp, but as the 2nd-or-3rd biggest club in the country; and they’ve also seen the biggest fall from grace that I can remember a massive club experiencing, and far worse than what we’ve seen at Liverpool (but that doesn’t make him a crap manager). Porto do brilliantly with buying and selling, but they’re part of the “Big Three” that usually end up in the Champions League every year. None of these clubs is the 5th-richest in a four-place system, or the 4th-richest with three places.

Let’s be clear: Atletico, Porto and Dortmund are selling clubs. They have built excellent sides over recent years by selling their best players and reinvesting wisely; as did Lyon and Udinese before them. They cannot keep their elite players, as they are not at the top of the food chain; so they sell them and try to improve. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. They try to buy young, hungry players on the up; but those players may be inexperienced, and not quite ready. Older players often cost more, and demand bigger wages, but the downside with them is that they may have lost their desire, or accumulated niggling injuries and wear-and-tear. When the younger signings work, it’s the best way to do business. When they don’t, those clubs should have done the opposite. Obviously.