By Paul Tomkins.

The notion that Liverpool have bought success, as opined by the Manchester Evening News’ Stuart Brennan, is frankly ludicrous. He also Tweeted that:

…while Liverpool do have a couple of home-grown lads in Gerrard and Jon Flanagan, it is outrageous to suggest they have not bought their way to success.

Liverpool have of course spent some money to get into the hunt, but nothing compared with that spent by Chelsea, Man United and City in winning their titles of the past decade, during which time football became about billionaires and even trillionaires. Liverpool have five huge games left, but if they win the title it would make them the ‘cheapest’ champions in many a blue moon.

Brennan throws out a random series of numbers in his article and tweets – Liverpool’s gross spend in the past six years, then the Reds’ net spend over the past 20 years – without acknowledging any context, such as Liverpool becoming something of a selling club between 2009 and 2011 as the cowboys, Gillett and Hicks, looked to recoup all the money they could, and FSG offloaded anyone who wanted out, or who needed moving on (Alonso, Torres and Mascherano were all sold in that period; those three alone raised £100m.)

As I noted a few years ago in Pay As You Play, the argument of net spend is very flawed indeed; the only thing in its favour is that it’s slightly better than using gross spend, which is virtually meaningless. (A team can have a gross spend of £100m in a season – Ooh, big spenders you say! – but at the same time sell its entire existing team for £10m or £200m, and it still has that same £100m gross spend. It’s like looking at the background of the Mona Lisa and calling the work a landscape.)

The biggest problem with net spend is deciding where to make the cut-off point; because whatever you choose will always be fairer to some than others.

You can start with the moment a certain manager arrives, but if, for example, you take Jose Mourinho in 2004, he joined a club that had spent £100m the previous summer (which is around £200m in today’s money). So it wasn’t just the £100m he himself went on to spend in 2004, but all the money leading up to that point. Mourinho might not have rated everyone he inherited, but it was a squad full of top internationals to pick and choose from.

Net spend is even more problematic with Manuel Pellegrini (who was my choice to replace Rafa Benítez in 2010), because he inherited an expensive squad packed with the talent bought during Mancini’s time, and beyond. After all, it’s not like a manager starts with no players at all, is it? He doesn’t start from scratch, but from where his predecessor left off. If every manager had to assemble an entire squad of their own at the start of each season, net spend would make some sense.

Pellegrini hasn’t spent an absolute fortune, mostly because he already had Hart, Kompany, Silva, Aguero, Toure, Zabaleta, Dzeko and various other world-class and/or top Premier League players (plus Joleon Lescott). Therefore net spend is an irrelevant argument in this case, as it is in many others. This shouldn’t detract from the fine job he is doing in changing the playing style, and the fact that City’s summer signings were mostly excellent value for money.

How much a team costs, once inflation is taken into account, is what matters; as we showed in our book and various articles. Our Transfer Price Index inflation system is not going to take the vagaries of football into account – unexpected things happen – but by contrast, gross and net spend arguments seem petty and misguided; it’s like going back in time, to a pre-enlightened age.

(Note: TPI inflation is based on the average price of all Premier League transfers each season, which leads to far greater rises than “standard” inflation. TPI inflation means that transfers are approximately ten times what they were in 1992, and twice what they were in 2004.)

How much a squad cost to assemble only tells you so much of the story; it shows the existence of a safety blanket, but not how much that reserve gets relied upon. Ultimately it’s the cost of the talent that plays that determines whereabouts a team usually finishes. We call this the £XI (average cost of the XI over 38 games after inflation is applied). It usually predicts to within two places of where a team will finish, making it more accurate than using squad costs.

Obviously the bigger, costlier squads have expensive players to replace expensive players when rotation or injuries occur; and while you get costly flops on the bench, on the whole you get better odds of a success when buying someone for £30m than £3m (even if it’s still never guaranteed, and we can all name £3m signings that proved better than £30m ones; but the overall rule is that more money increases your chances of a gem).

Inflation is vital when assessing or comparing teams assembled across many different seasons. You cannot say that when Rio Ferdinand cost £30m in 2002 it was roughly the same amount as Marouane Fellaini (at £27.5m) in 2013. Ferdinand’s fee was huge, a British record, for an elite player who’d possibly make the all-time Premier League best XI in his position; Fellaini’s was upper-mid level fee, and no more, for a mid-level footballer with a giant sponge on his head.

Go back to 2009, when United were at the peak of their powers; they had already locked down a player in Ferdinand whose fee, when adjusted for inflation, was by then up around the £50m mark (reflecting that he was the best centre-back around when taken off the market by Alex Ferguson, and he was still performing at a very high level). Funnily enough, the British record rose shortly after, in 2011, to … £50m.

In the past people have used the example of Ferdinand to say to me “well, he’s not a £50m-£60m player now, is he?”; proof, therefore, that the concept is flawed. But actually, the thing with Ferdinand is that he shows up as part of the squad cost (just as he’s still a huge wages drain on the United accounts), but he barely registers in the £XI – because he’s now old and doesn’t play that much. Therefore it doesn’t particularly skew the figures. It bloats the squad cost, but we ignore the squad cost.

Individual players are rarely, if ever, worth exactly what they originally cost, or what that fee amounts to with inflation. Clubs pay the fee at the outset, before he pulls on their shirt, with only some reflection of future performance seen in achievement-related payments. It’s a punt, an educated guess at value. Unlike transfer fees, wages (eventually) get upgraded to reflect performance, and they’re obviously a good guide too; but they don’t take into account injuries, which means that a club’s five highest-paid players could all be sitting in the stands for six months, not out there affecting the result.

Overall, though, once a club has shipped out its costly mistakes, it will tend to have a mixture of free, cheap, expensive and club-record breaking signings in its squad, with the best of those appearing in the XI. The law of averages brings this spending into something resembling a logical hierarchy. Of course, teams can perform below their cost/value, like United this season (or City in 2012/13), or above it, like Liverpool in this campaign (after a few years falling below the expected return).

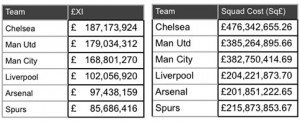

In a follow-up to the piece, Stuart Brennan tweeted that the Liverpool team at the weekend cost over £100m, as if this was 1998 and £100m was still a big deal. With inflation, the Reds’ £XI (averaged over 33 games) is £102m, which ranks them 4th in 2013/14, just as the squad after inflation cost also ranks them 4th; but in both cases a mere fraction ahead of Arsenal. I’m guessing that the Gunners’ current wage bill is higher, due to regular Champions League participation, with Liverpool’s ranking 5th, ahead of Spurs (whose £XI is £86m).

What about the above says Liverpool have any right to lead the table in April based on outlay?

An £XI of £102m pales in comparison with City’s £169m, United’s £179m and Chelsea’s £187m. In the past decade, the cheapest £XI to win the title is £164m in 2011, and the average is £184m.

Along with the fact that no-one jumps from outside the top four to challenge for the title anymore (you have to go back to the ‘80s for the last time a team jumped from 7th), the reason I felt Liverpool stood no chance was that the side is so relatively cheap. So while Brennan may have a point in that Liverpool aren’t total paupers by Premier League standards – and I’m not sure anyone said they were? – in the relative terms of finishing 1st they actually would be.

Random figures like the gross spend of the past six seasons, in which the Reds have also shipped out several dozen players, or the net spend in the Premier League era, given that it includes a decade where Liverpool spent terribly, seem almost arbitrary. (How much money did the Reds waste between 1992 and 1999? The answer is a ton. And what does it have to do with Brendan Rodgers?)

To put it further into context, Chelsea’s current squad, with inflation, cost almost half a billion – £476m; with United’s at £385m and City’s £382m. None of these clubs has reached even 50% in terms of the transfer costs of players making the £XI, suggesting a lot of fat on the bone, whereas Liverpool are at 64%.

This could of course mean that those richer clubs have been more injury-hit, but the figure tends to reflect squad depth more than anything; almost two-thirds of the Reds’ expenditure has, on average, taken to the pitch, whereas the richer clubs have had more in reserve.

In Rodgers’ favour, he hasn’t had to play his stars in Europe or extended domestic cup runs; in my view that has helped even the playing field a little, because bigger (and usually costlier) squads are required.

But even so, it’s not success that’s been “bought”. All that was bought was a decent chance of the top four, with logic dictating that the top three would be the same as last season (although Moyes was always like to turn expensive players into mere drones like Hodgson at Liverpool), and that, based on £XIs, Arsenal, Liverpool and Spurs were fairly evenly matched in the race for 4th.

One thing TPI proves in City’s favour is that they didn’t “buy” success in terms of assembling costlier £XIs and squads than United or Chelsea; but that, like Blackburn in 1995, they levelled the playing field. Back then, United had already accrued a whole host of expensive players (breaking the transfer record in 1993 on Roy Keane and 1995 with Andy Cole), to go with their emerging golden generation; the difference being that it feels more false if a team is assembled in two years rather than six or seven, and even more so if the money is pumped into the club in all at once, without having been generated in the traditional way (turnstiles, shirt sales, TV revenue).

The game-changer in English football was the arrival of Roman Abramovich. That was the one huge jump in investment; City didn’t blow their rivals out of the water in the way that Chelsea did, not least because Chelsea still had their wealth when City joined the party. Even now Chelsea have the costliest squad and most expensive £XI, and despite Mourinho’s ludicrous protestations about his brave young troops, are the joint-oldest side in the top four, at a very experienced 28.1; the exact same age as City based on the starting XIs so far. Liverpool are a full two years younger, at 26.1. So Rodgers has neither money nor experience on his side.

Another way to override the TPI predictions is by using loans, a subject covered well by Martin Samuel when discussing Everton this week. If you take his guess that Lukaku, Deulofeu and Barry would cost a combined £50m, then assuming they played regularly, their £XI would rise from the very modest £40m to £90m, making their contention for the top four more understandable (even if Roberto Martinez has still done a great job).

So there you have it. Liverpool are young, inexpensive and inexperienced when it comes to winning titles, and yet lead the table with five games to go. City probably remain favourites, but anything less than a point on Sunday, and they will face an uphill struggle.