By Mihail Vladimirov.

Liverpool would have continued with the same XI used for the past two games if it wasn’t for the Lucas ban that enforced a change. Sterling came in as right wing-back, enabling Henderson to occupy Lucas’ spot beside Gerrard.

For Palace Delaney was surprisingly fit to start, and he replaced the injured Gabbidon. With Dikgacoi injured too and Bannan unexpectedly left out of the match squad (without any indication he was injured), Holloway had to make two changes in his midfield. In came O’Keefe and the available again Puncheon (he was unable to play in the last game as it was against his parent club, Southampton). In attack Gayle was replaced by Jerome.

Both teams lined-up in their recent formations, but it was how Palace seemingly were told to interpret it which added extra tactical interest early on. Still, for all the promising tactical battle, especially in the first half, the game proved to be too easily decided mainly thanks to the obvious gulf in quality and how atrociously poor the visitors were in defence, as anticipated.

This being said, this analysis won’t consist of the usual in-depth breakdown of how the game unfolded. It will still cover chronologically what happened tactically in the game. But given the lack of a tactical battle per se and the game being wrapped up in the first 20 minutes, an additional part will be added to this analysis, going through Liverpool’s formation and how the players acted within it to cover the most important aspects of Rodgers’ presumed game plan.

With Liverpool’s element covered later on, and to provide some context to how the game played out tactically, it’s important to start by briefly outlining the key parts of what looked like Palace’s starting strategy.

Palace’s lopsided 4-1-2-3

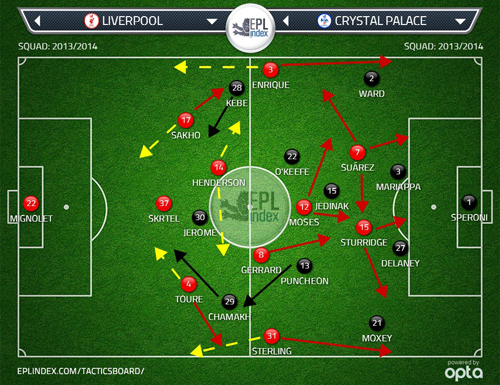

Based on the starting XIs it was assumed Holloway would start with something resembling a 4-4-2 (morphing into 4-2-4) formation. This was based on the fact there was only two natural central midfielders (Jedinak, O’Keefe), two natural wide men (Kebe, Puncheon) and two natural forwards (Jerome, Chamakh). The only possible alternative to this seemed to be a 4-2-3-1 with Puncheon in the hole ahead of the two midfielders, with Kebe (right) and Jerome (left) flanking Chamakh. Hence the surprise in seeing the team actually going for a lopsided 4-1-2-3, with Puncheon as part of a proper midfield three and Chamakh deployed as a sort of wide target man, with Kebe on the right and Jerome up front.

What bore the main tactical interest was the fact that Puncheon and Chamakh weren’t fixated to act as per what their starting positions dictated – the former as a central midfielder, the latter as a winger. The way they behaved when attacking suggested their nominal positions were more of a decoy, on top of them looking like the most important part of how Holloway intended to threaten Liverpool.

For Palace, three bodies in midfield, in a 1-2 format hence levelling the numbers with Liverpool’s 2-1, meant two key things. First, not giving the opposition a clear area of strength; and second, additional possession stability and potentially increased attacking fluidity (based on the possible patterns within a midfield and a front three that combine to offer diverse but complement attacking movement).

The first point was crucial given it was logical to expect Liverpool would dominate with the ball right from the start, meaning Liverpool would be mainly in their attacking mode. Having only two midfielders against a team going to create with three midfielders (for a second game running Moses acted more of a third midfielder than a third forward – but more on this later) and attack with two such quality and roaming forwards, is always a huge gamble. More so if you know your players have inferior players all over the pitch. The second point probably has to do with how Holloway wanted to give his team increased chances to actually be threatening on the break in the rare situations it would have the opportunity to do so. And all of this based on the potential expectation of Holloway that Rodgers would continue with the 3-4-1-2 shape. Not that it was hard to guess this, given the media coverage of this formation by Liverpool’s management in the days before the game.

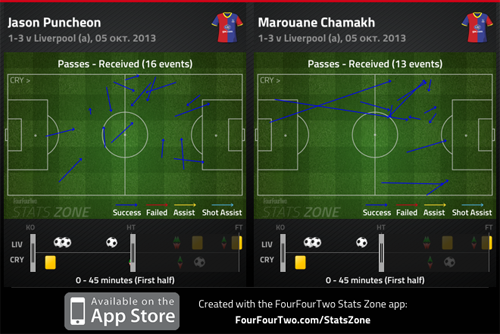

As the above diagram illustrated, when the visitors were going to break forward, Puncheon was quick to drift wide and become the de-facto left winger, allowing Chamakh to move infield and form a forward duo with Jerome. By having two wingers and two forwards in attack, in theory Palace would have a greater chance of breaching Liverpool’s back three unit, especially when compared to the variant of having one poacher up front (Jerome), a target man playing on the one flank (Chamakh) and an inconsistent dribbler on the other (Kebe). This is not only because of the increased numbers of attacking bodies but also due to the increased movement fluidity and cohesion increasing the chance to actually stretch the back three unit.

The theory suggested that having a target-man and a poacher up front could enable that pair to force the back three unit to stay narrow in order to retain a spare man. Added to this is the possibility of the diversity provided by a target-man to drop deep or stay high up (or as it was – move infield) to collect the ball and either try to feed his partners or go for it himself; combined with a mobile forward pinning back the back three unit or threatening to stretch them laterally, allowing for the wide men to offer the reverse movement and cut infield.

In practice, with Liverpool dominating in terms of possession and territory, it was a case of Palace having different ways, all of them suitable, to be dangerous on the break. Jerome’s pace up front could have served as a direct counter-attacking option either in behind or down the channels (especially when the back three unit pulls wide as per the requirement). Chamakh’s presence out wide enabled the team to have a secondary counter-attacking threat with him either collecting diagonal balls to knock down for the onrushing Jerome (drifting laterally or sneaking in behind), Puncheon (bursting from deep) or Kebe (moving infield); or move infield himself – once Puncheon starts to drift wide – to collect balls in the air or on the ground in good finishing positions.

Two situations in the first ten minutes in particular showed the efficiency of Holloway’s supposed tactical idea. In the 8th minute Puncheon moved to the left wing, once Chamakh and Kebe were infield, overloading that zone and helping him to have a ‘window’ to cross dangerously in the box from where Jerome’s header (due to him not connecting properly with the ball) went just off target. It should be noted that the congesting provided by Chamakh and Kebe being on the edge of the box with Jerome forced Liverpool’s back line to crowd out that area too, leaving the space in behind vulnerable as only Enrique was in position to cover. The quick combination to allow Puncheon to cross caught Enrique up against the quickly onrushing Jerome, who positioned better to connect with the ball.

Less than a minute later, Palace regained the ball in their third. It was a case of two passes later (Mariappa to O’Keefe and O’Keefe to Chamakh) leaving Chamakh, in-cutting from out wide, to head in the channel between Toure and Skrtel clear through on goal, if it wasn’t for his poor first touch. Still, it should be noted that Skrtel and especially Toure were also quick to close him down and limit his shooting angle.

There was another situation, in the 24th minute, that showed Palace’s ability to quickly morph in attack and commit bodies forward. In contrast to the above two, this situation was largely of Liverpool’s own making, thanks to a misplaced pass by Sterling being intercepted and leading to Palace breaking forward through the middle, with the back three unit being spread out to help transition the ball from deep with Gerrard moving higher up. Once Sterling’s pass was intercepted, it was a case of of Palace swarming with Jerome drifting wide (to secure more space for Chamakh who was on the ball), Kebe being already infield and O’Keefe surging forward from deep. With Toure and Skrtel narrowing to both cover Kebe and block any potential shoot from Chamakh, and Henderson trying to track back Chamakh in order to dispossess him, Gerrard ought to have tracked the runner coming from his zone – O’Keefe – with Sakho staying a little bit to the left to cover. Instead it was a case of Sakho being sucked too central with Gerrard (as so often) caught ball-watching and not tracking the midfield runner. Fortunately for Liverpool, Sakho was alert enough to see Gerrard was failing to track back, and his big strides blocked the dangerous shot from the incoming O’Keefe.

The next situation, around a minute later, showed Palace’s ability to put emphasis on Liverpool’s inherent weakness down the channels through playing with three centre-backs and only one wide player. Mariappa booted the ball forward towards Jerome, with Skrtel and Sakho both going for the ball. It resulted in neither clearing it assertively enough, with the ball scrambling in behind for the unmarked onrushing Kebe. Still, credit to Skrtel for quickly recovering his position and rushing back to prevent Kebe having a clear shoot on goal (although it could be said Kebe ought to have done better). The situation resulted in Jerome having a shot which would have ended into the back of the net via a rebound off Kebe if it wasn’t for Mignolet’s brilliant reflex save. But the clearances ended with Puncheon who blasted the ball way over the crossbar.

The three different stages of the first half

What made a positive impression in Liverpool’s overall play, during the first part, was how they clearly divided the half in three different stages. It’s hard to say with any certainty whether this was a pre-planned aim for the team to behave in exactly that way in these periods. But it seemed like the team was prepared and knew what to do at the start and then – based on how it goes on – how to then adapt accordingly.

The rest of this article is for Subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]