Published March 6th 2022.

Last month, a leading data analyst at one of the world’s most famous universities (and a long-time TTT subscriber) emailed me some findings he’d unearthed doing a deep dive via FBRef.com, relating to how badly referees treat Mo Salah in comparison to pretty much every other player.

I’ve long noted how few penalties Salah wins in relation to the fact that he is almost always the Premier League player who has the most touches in the opposition box each season. He is a dribbler, a darter, a runner-off-the-ball, and a man you don’t want to let get shots away. Yet he gets almost nothing from referees. But I’ve never looked closer at the general fouling trends towards the Egyptian.

The world-class analyst ran the number of fouls Salah receives per match against a list of roughly similar attacking players from across Europe (i.e. no lumpen 6’5” strikers), but with most of the comparisons focusing on players in England.

As such, I invite you to pin the tail on this particular metaphorical donkey (no, not Harry Maguire).

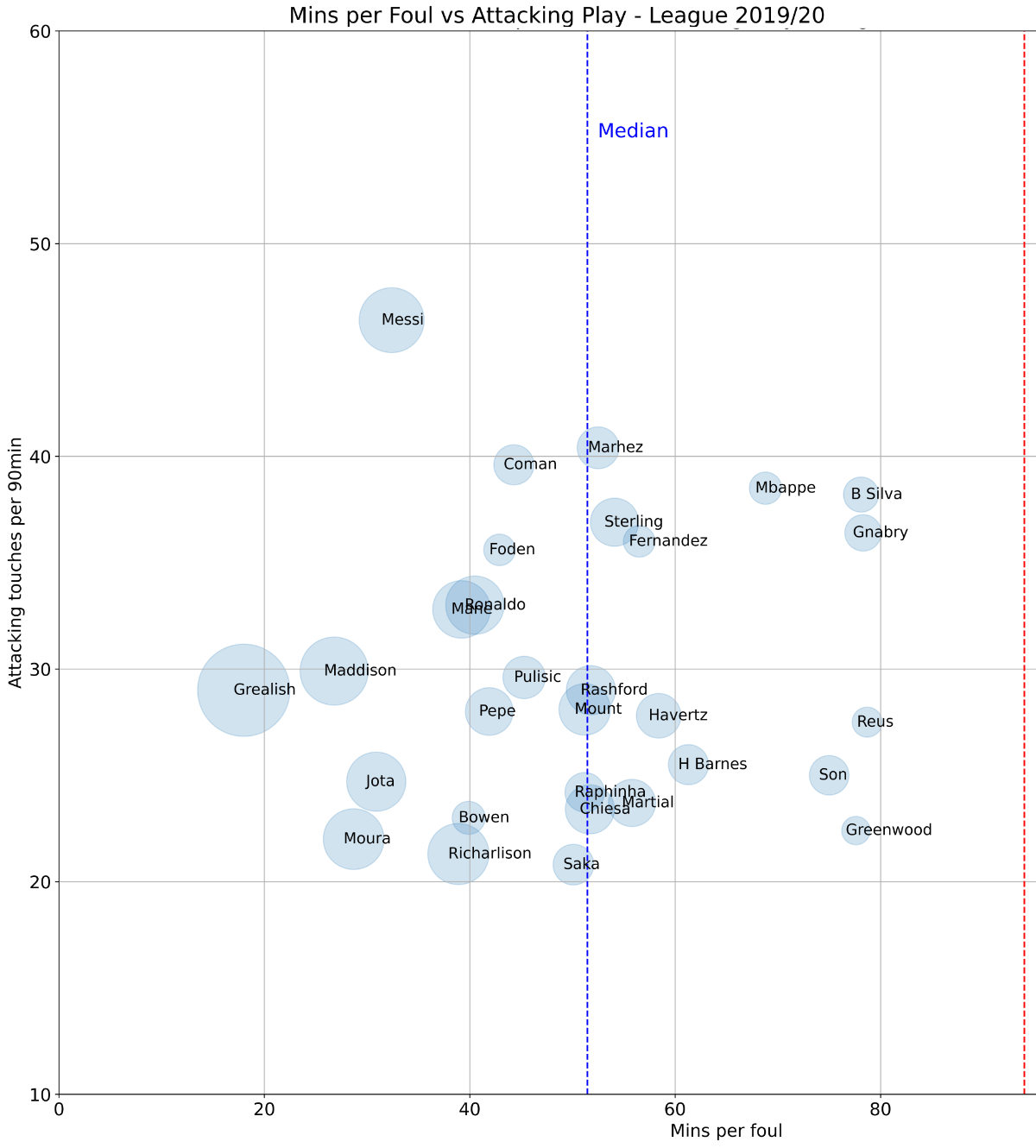

Where would Salah sit in the graph below, once I’ve explained what the graph actually plots?

The graph relates to free-kicks won in 2019/20, when the Reds won the title, but almost the exact same pattern was seen the year after, so the position would also be more-or-less true for him in 2020/21.

The metric is the number of free-kicks won in relation to the number of touches of the ball in attacking areas (per 90 minutes, so it’s all comparable), and the graph is within the outer “outlier” line of too many free-kicks to make sense (the left edge) and the outer “outlier” line of too few free-kicks to make sense (the right edge). The size of the circle means the bigger the bubble, the more free-kicks won.

(Quick aside: it’s interesting to see Jota win a lot of free-kicks with Wolves. You can guess which direction on the graph he has moved since joining Liverpool.)

Okay, where did you place Salah?

As you can see, none of the players are beyond one foul per 80 minutes, which takes you to the super-outlier zone at the red line, and Jack Grealish sits at a foul less than every 20 minutes.

Well, here’s the catch.

Salah didn’t even make it onto this version of the graph.

Not in 2019/20, and not in 2020/21.

(As of this season he is just about on the graph.)

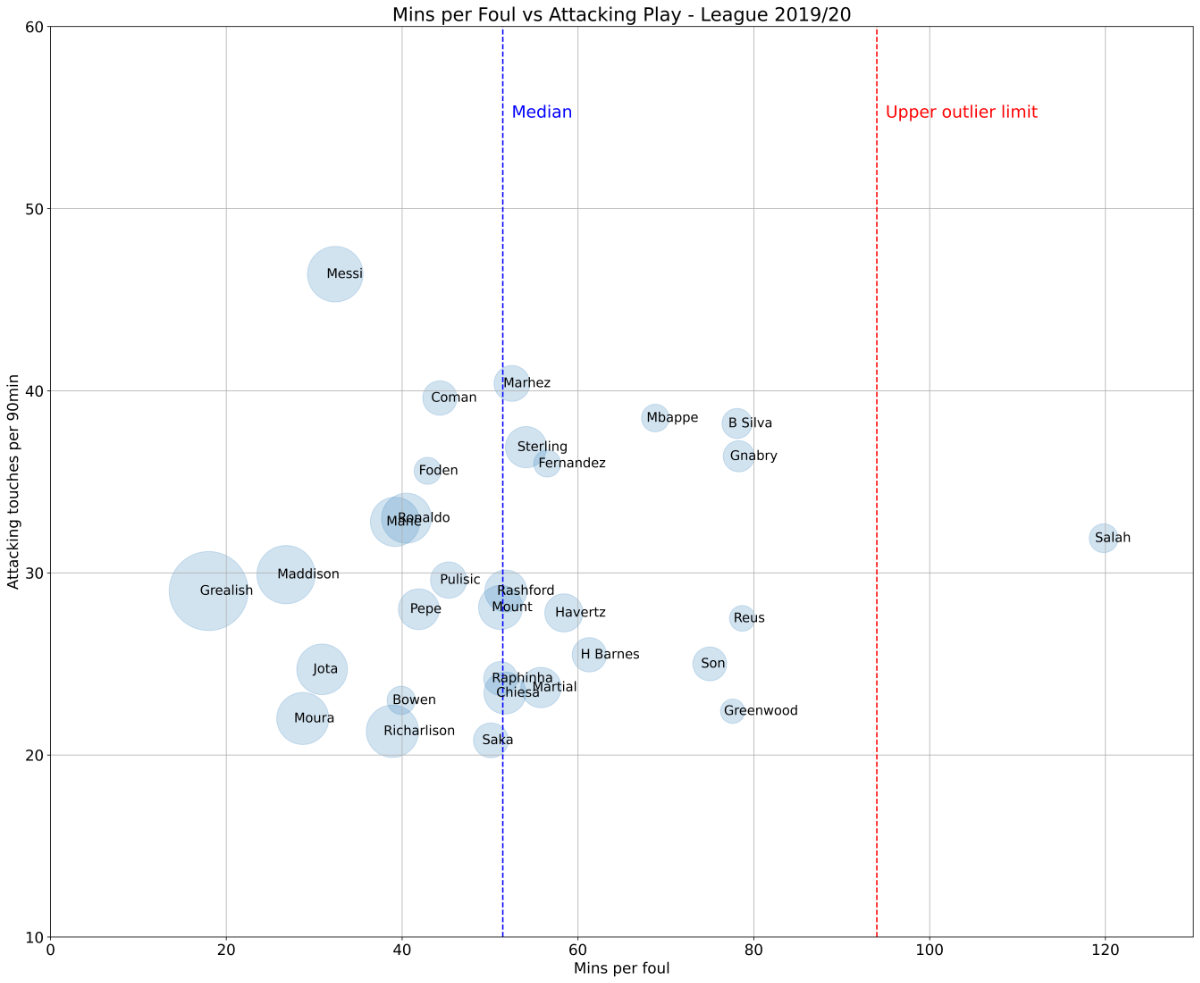

You have to widen the graph to take in the outlier region, where he sits, alone, as an island of his own in a sea of “this should not be happening” space. He is 50% more harshly treated than the next player, if my maths is any good.

You essentially need a whole new graph.

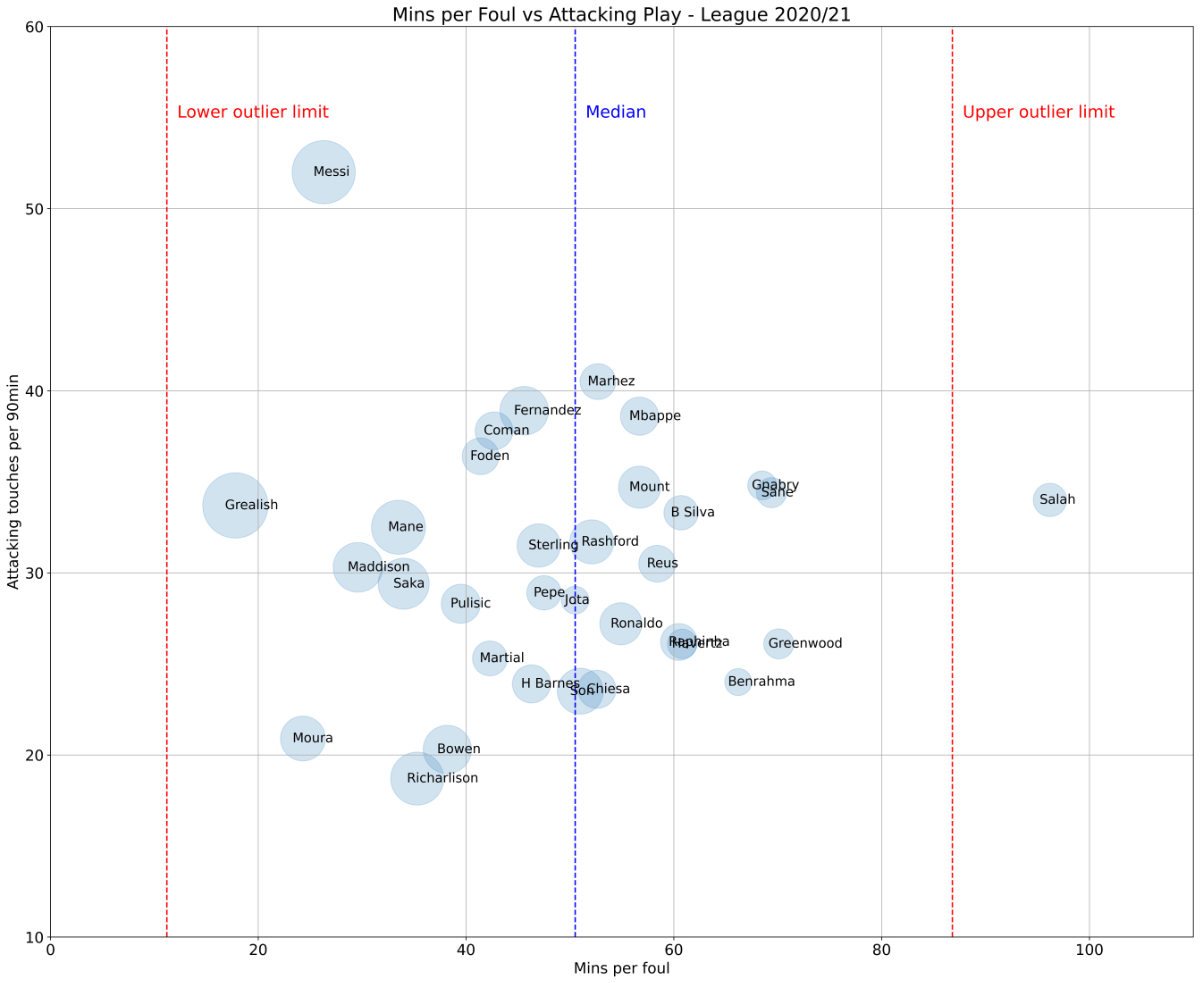

The exact same pattern appears the season after, too (below), albeit not quite as “off the charts”, but still, well, literally off the charts.

Literally, literally off the charts.

While some players were winning a free-kick every 20 minutes, Salah needed to play the equivalent of full-time and extra-time in a Premier League game to get just one.

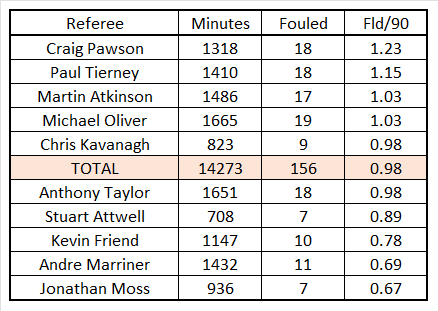

This season he’s come in from one every 120 minutes to one every 100 minutes (still insane), but some refs give him just two free-kicks every three 90 minutes of Liverpool games they officiate when he’s on the pitch: one foul every game and a half.

Remember, this is a player hardly ever booked for diving. He can exaggerate his falls, of course, but which striker doesn’t after being fouled? (The entire notion that a foul has to be enough to take you off your feet is moronic.)

Far bigger, stronger players collapse in a heap on a regular basis, but if there has been a foul, it’s often to highlight it to the refs, who punish strikers by waving play-on if they do stay on their feet despite the infringement costing them possession or even a shot at goal. We can all see that. Whenever Salah is tripped at pace, slow-mos remove all context, and he’s labelled as going down to easily.

Several less-talented, less-skilful, less-fast and less-committed English players won free-kicks at 5x or 6x the rate that Salah did between 2019 and 2021, and continue to do so around 4-5x as much this season. (This was before Jon Moss gave Salah nothing yesterday, and thus increased his minutes per foul for this season.)

So, when Salah was booted up in the air after 15 minutes against West Ham, nothing was given by Jon Moss. Two more potential fouls before the 19th minute were ignored, albeit both could have been fair, hefty tackles, as we didn’t get to see replays. Another, later in the match – a clear grab – was ignored. There were your four fouls, two of them clear, two of them less clear, that lesser English players routinely get each match.

(I mean, James Maddison? PLEASE! At least Jack Grealish is a dribbling freak … albeit that also applies to him at 4am after a night out in Ibiza. Maddison’s game-plan is often to lay the ball off and the jump into the air. He’s fairly skilful, but not quick, not a constant goal threat, but has a stock move to simply win free-kicks. And yet social media and phone-ins don’t go mad about James Maddison.)

Salah is also constantly fouled off the ball, or when just about to receive it. His runs are so dangerous that he gets blocked, tripped and shoved. Every game someone taller and stronger has him round the neck.

We’re talking about one of the top five attacking players in the world on a consistent basis over the past 4-5 years, and you’re telling me he’s only getting fouled once every 1.3 games?

Perhaps half the time, referees just guess. It’s just guesswork. Refereeing is guesswork, and in England, it’s guesswork by portly middle-aged men who can’t run, and whose brain processing can’t be as sharp as someone younger and fitter; managed by one of their peers, also in his 50s.

It’s just prejudicial guesswork based on biases, as I’ve shown in how penalty decisions are so unevenly distributed, so as to favour English players in both boxes to statistically significant degrees.

(Based on all 600 penalties over a seven-year period, with a different data analysts and scientists helping on that, including the statistical significance portion run by a Liverpool University professor; and the data on other aspects of fouling collated and checked by a graduate of Harvard and Oxford who works as a project leader at one of the world’s biggest companies. While there are still silly jokes on TTT, often made by me about David Moyes’ face, we have some very smart people in our ranks, who know a shit-ton more about data analysis than I do.)

Are English strikers really so much better that they should win more penalties than expected? Are foreign defenders so much worse that they should clumsily concede so many more than expected? The best players at both ends of the pitch are mostly foreign, with a small number of England internationals the only ones who can get close to matching them. Ergo, something is very wrong with the way English officials make decisions.

The aforementioned article from a year ago, pulled together other weird aspects of refereeing that we’d been noticing for a while. Once you deep-dive the big data, it undermines your faith.

I’ve been noting for years that Liverpool win far fewer penalties than expected per penalty box touch, and that since Jürgen Klopp arrived in 2015, rank outside the top six for clubs with the most Premier League penalties. Indeed, but for the slight balancing out by just two refs, Liverpool would get penalties at the same rate as a team in the relegation zone.

Due to being a top six side for pretty much all of the Premier League era, along with only Manchester United (Chelsea and Man City haven’t always been big clubs, and Arsenal have fallen a long way since 2004), it makes sense for those two clubs to have the most penalties since 1992, but since 2015 Liverpool rank well behind other clubs. This, despite incredible attacking metrics. Clubs like Leicester City, Brighton and Crystal Palace win more penalties than Klopp’s Liverpool.

(To show this is not my bias, Liverpool always got more penalties when there were more English players in the side. Lots of English players equalled lots more penalties. As the number of English players rises and falls, the number of Liverpool penalties follows suit.)

Again, it’s often guesswork by officials, and guesses favour your “friends”. Look at how little clue refs have when the ball goes behind as to whether or not it’s a corner or a goal-kick. It’s often difficult to see, so they go on who appeals first/loudest, who it’s easier to give the decision to (usually a goal-kick instead of a corner), and maybe which players they are on first-name terms with and which they dislike or have biases against. Some referees clearly dislike Klopp, despite him never putting pressure on referees before games. (Yes, he shouts at them during games, but he shouts at everyone. Only poor little flowers would take this to heart.)

That’s why I thought VAR would help, but in England the PGMOL use VAR to confirm that their mistakes were not mistakes, rather than to seek clarity. Instead, we get the gaslighting. (Again, this was the same ref/VAR team that screwed Liverpool over at Spurs to such a farcical degree.)

After the latest bit of gaslighting, Mike Riley finally spoke to the English owner of Everton and to the English manager of Everton, to apologise for the mistake the English officials made. Football, with Mike Riley’s gang of 50-something mates, feels like an old boy’s network of chumminess and nonsense. Would Riley have phoned Rafa Benítez or Farhad Moshiri? Would Riley phone Jürgen Klopp or John W Henry? It all feels a little like cronyism.

And of course, that decision, fudged and fumbled into nonsense before the apology came, affected the title race, too; the same ref and VAR as covered here, and some previous gaslighting.

Do the PGMOL do any data analysis to show how much they get wrong? I doubt it.

Meanwhile, Liverpool are one of the lest-helped teams by VAR, yet #LiVARpool trends on the rare occasion that people can’t tell their confirmation bias (in their case, what they shit from) from their elbow.

The aim of the data analyst who collated the Salah report has been to expand the list of players, at my request, before publishing; but I thought I’d run his initial findings here, after a match with a ref who was not going to give him a single thing all game.

While I may spend 90% of the little time I log onto Twitter moaning about refs, the use of VAR and the PGMOL (which makes me not really worth following, as at times I seem a like a gibbering nutcase), it’s because I know that the data shows something is very, very wrong.

Each incident is “just another mistake”, but the bigger picture is one of institutional failure. Sometimes it will just be a genuine error; other times it’s confirmation bias, or personal animus, or whatever it is that skews the data beyond a point of realistic expectations.

As noted by Matthew Syed in Black Box Thinking, with botched operations at hospitals where the surgeon says “it was just one of those things”, it’s not until an overview is taken of how many “just one of those things” happen that we know if something is awry.

Any decent governing body would look into how Mo Salah can receive so few fouls he’s literally off the charts. The PGMOL, therefore, will not.

Addition: 15th March 2022

Saturday saw an incident when Mo Salah, through on goal, was dragged to the point where his shot was affected, but not to the point where he was hauled over. No penalty was given. I didn’t even expect it, as it’s Mo Salah. An illegal grab of the shirt or shoulder when shooting should be a penalty, if it puts the striker off balance. It’s cheating, just as much as other forms within the game.

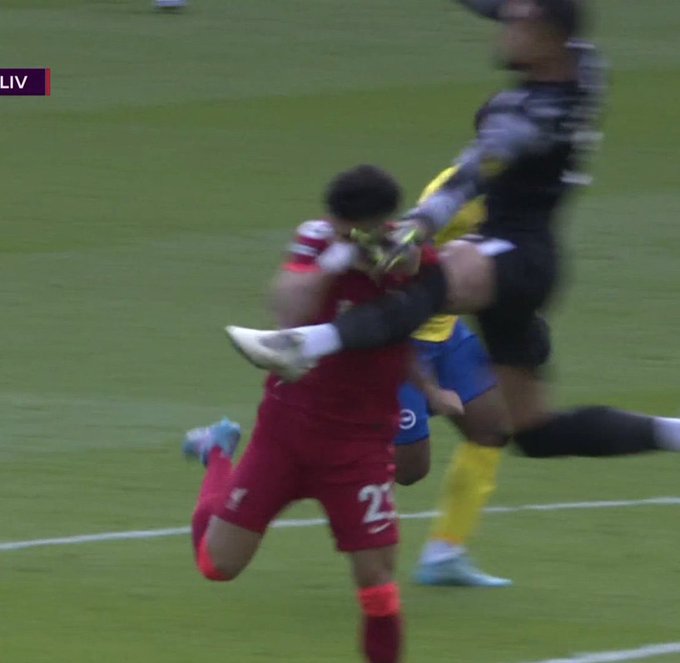

This was the same game where no red card was awarded for the most red-cardable offence you can get: hitting someone in the upper chest with your knee whilst smashing them in the face with your hand. (And the video looks even worse than the still image.)

This was the same game where no red card was awarded for the most red-cardable offence you can get: hitting someone in the upper chest with your knee whilst smashing them in the face with your hand. (And the video looks even worse than the still image.)

Yes, it was accidental, but the recklessness of it could have left Luis Diaz in hospital. It was no higher than Harald Schumacher’s infamous foul on Patrick Battiston. It’s no exaggeration to say that Diaz was lucky to not lose his teeth, break his neck, end up in traction, like the poor French player 40 years ago.

Keepers were protected for a reason (forwards could go in too aggressively), but now they can produce possible career-ending recklessness, and as with Jordan Pickford last season, not even get booked. It makes zero sense, to have opposition player safety endangered just because they are goalkeepers. Diaz could have joined Virgil van Dijk in needing a massive operation.

That the VAR cannot find the confidence to make this decision speaks of an avoidant culture at the PGMOL, where people are paid good money to say “nope, I saw nothing”. (This is why they have to be miced-up, and on camera, discussing their thinking, if any thinking takes place.)

I don’t know how many baffling decisions affecting the title race I can keep listing, but referees appear scared of giving clear red cards early in a big game as they’ll “ruin the contest”. This is no way to operate. Thus, you get Harry Kane not sent off early in Liverpool’s costly 2-2 draw at Spurs, and no penalty given for a NFL tackle on Jota; but Andy Robertson gets sent off late in the game, when it seems to feel “safer” to the VAR. This is not acceptable.

A clear bias – seen in the data – against certain players, and certainly overseas players, is also not acceptable.

I’m constantly picking fault with officials because I track the data, and find patterns that need some explanation. It’s a world-class game officiated in an amateurish fashion, with an apparent cronyism in how many 50-something peers of Mike Riley still referee, barely chugging around with their middle-aged spread.

I’m hugely biased, of course, but big data backs up my claims. If I don’t see something in the data, I let it go, or change my view in line with the data. Of course, I take a few lame, cheap-shot jokes at rival players and managers (I’ve never denied being a bit of a dickhead), but I still try to stick to proper evidence in serious claims.

By all means go away and do your own analysis with the data, if you think I’m too Red-eyed.

(As an example, I had an issue with Mancunian Anthony Taylor after he failed to send off Vincent Kompany in 2019, as another major example of early-game bottling. But actually, the data I went through a year ago suggests that he’s pretty fair to Liverpool overall, as one of only a small number of referees who fit into that category. The vast majority of officials rarely give Liverpool big decisions, especially at Anfield, and as I keep saying, especially at the Kop end – where a fear of giving a decision is clear, as they’ll get mocked on social media, by rival fans, and opposition managers, for bowing to the Kop’s power. Martin Atkinson hasn’t given Liverpool a penalty, or a red card against an opponent at Anfield since 2015, when Steven Gerrard lambasted him in his autobiography, and when Jürgen Klopp arrived. Stuff like that starts to smell a bit fishy, especially as Atkinson gave Liverpool big decisions at a fairly normal rate – every few games – before then. We all have our biases, but the idea that officials can’t have personal grudges or biases of their own seems preposterous. They are human, but their human errors should be addressed.)

Keith Hackett, still ranked one of the top referees in football history (source: International Federation of Football History & Statistics), worked as general manager of the Professional Game Match Officials Board (PGMOL) in the mid-2000s. So, he knows what he’s talking about, when discussing Mike Riley and the current PGMOL.

This weekend he tweeted disbelief at the challenge on Diaz not resulting in a red card, and further cutting remarks about the way the PGMOL is now run:

“@HACKETTREF what will it take for Riley to be held to account for the utter incompetence of his employees and the appalling use of VAR. This #CHENEW is showing how far standards have fallen”

“We see it – he [Riley] and the Board of Directors of the PGMOL have their heads in sand. They clearly know nothing about the game.”

It’s hard to disagree. While football has a lot of big issues to deal with right now, having officials few people have faith in – for good reason – is not helping the game either.

Note:

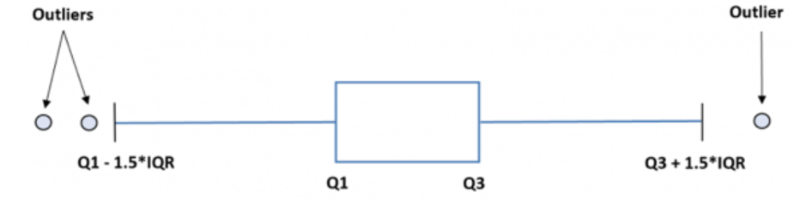

Note about defining ‘outlier’ from the analyst:

An outlier is an observation that lies abnormally far away from other values in a dataset.

Defining Outliers using the Interquartile Range

https://www.statology.org/find-outliers-with-iqr/

Interquartile range (IQR):

- difference between the 25th percentile (Q1) and the 75th percentile (Q3) in a dataset

- measures the spread of the middle 50% of values (NB Q1 and Q3 are only equidistant from the median in a normally distributed dataset)

Outlier using IQR:

- has a value 1.5 times greater than the IQR, or

- has a value 1.5 times less than the IQR

This article will also be emailed via our Substack newsletter.