Despite sitting down last night and writing thousands of words on the ongoing refereeing/VAR madness that seems to blight every Liverpool game this season, I have saved them for another piece later in the week, given that we had already planned to analyse the whole season’s decisions in depth. This piece will be a largely VAR-free zone.

I felt that the Reds, against Everton, were actually playing well enough in the 2nd half for it to be a 1-1 draw, at the very least; just as they were playing well at Leicester, until the offside goal Leicester were allowed to score (compounded by Alison rushing out of his goal moments later, after Sadio Mané had been shoved to the ground in front of the ref), and just as it was tight against City until Alisson had a mad few minutes and passed the ball to City players in dangerous areas three times in a row. All of these games were tightly poised. The “team” was not playing badly; there were individual errors.

Liverpool missed big chances again yesterday (at least two clear-cut ones), and then Everton got that surreal penalty.

Twice during the game Jamie Carragher said on Sky that “Liverpool can’t keep using the injury to van Dijk” as an excuse, as if it was just an injury to van Dijk that was the problem. Talk about oversimplification.

Seriously, it was staggering in its reductiveness.

What made it all the more bizarre was that Carragher was rightly praising Liverpool throughout the 2nd half (talking about a much better tempo, good probing passes by Thiago, good crosses and attacking thrusts by Trent Alexander-Arnold, great positions taken up by Shaqiri that he said were causing Everton all sorts of problems, as well as constant praise for Jordan Pickford in the Everton goal for making big saves in the game as a whole) … until it went 2-0 with a penalty he rightly said should not have been a penalty, and then Liverpool had suddenly more-or-less dreadful all game; which was emotional, scoreboard sports journalism at its worst.

(Carragher is often excellent on Monday Night Football, when he’s calmed down and had time to think, and been given – or selected – some data and video to work with; and is absolutely terrible as a co-commentator. I think it’s very hard to do live co-commentary, and it’s not something I could do – but he seems particularly ill-suited to it. At times in the past he’s been too biased towards Liverpool, and now, since the spitting incident with Man United fans that almost cost him is job, and since Liverpool won the league and he went too far at times with his celebrations in the commentary box, he is either bending over backwards to look “neutral”, or just feels under pressure to jump on narratives.)

As I’ve said before, Liverpool were top of the table, going into the winter, having been without van Dijk for two months, even though his incredible range of attributes were – and are – missed; not least his sensational, game-changing passing from the back, although he’s elite in just about every area of the game offensively and defensively.

Joe Gomez, Joel Matip and Fabinho were all defending excellently after van Dijk’s injury. Was that not clear? Wasn’t that stated by most people, most weeks? Go back and read the reports. Go back and watch the games. Liverpool’s defending was excellent without van Dijk.

Jürgen Klopp’s men were keeping clean sheets, conceding very few goals. Maybe it meant the midfield had to protect the defence a bit more, and then the midfield had to literally become the defence.

One by one they fell. Now Henderson has picked up his third injury whilst playing as the emergency 5th-choice centre-back. It’s not a curse; but it is a Black Swan occurrence.

To say “Liverpool can’t keep using the injury to van Dijk as an excuse” is like saying a sprinter who loses his leg – in an accident, beyond his control – is making an “excuse”; the backup option, which the sprinter later takes to rescue some kind of athletic career, is a prosthetic leg – a one-of-a-kind bespoke carbon-fibre-reinforced polymer blade (applicable to both Joe Gomez and Joel Matip in this analogy) – but then in some new freak accident that snaps; and then, in an emergency, with nothing else to turn to and no time to find fancier solutions, he resorts to a wooden leg, which allows his “foot” to reach the ground, but has no spring, no give, no comfort. Rather than sprint, he can only limp.

Each time, the ability to be “elite” is reduced. Each subsequent compromise – which has to be a compromise because you don’t have 5th, 6th and 7th choice players who are good enough to replace world-class 1st choices by virtue of, er, logic (how can your 7th choice be as good as the world no.1?) – has been a further blow.

Or does Carragher think that the 6th, 7th and 8th choices during his time could ever have been as good as himself and Sami Hyypia, who had already played for five years in the same back four before, both at prime age, they formed an outstanding centre-back partnership?

(That, even then, was still not as good as van Dijk and Matip/Gomez at their best, as van Dijk with either Matip or Gomez are taller and faster than Carragher and Hyypia, and van Dijk is a better passer than any of them. That’s how good van Dijk and either Gomez or Matip have been. They won the league and the Champions League, lest anyone forget. It wasn’t all about van Dijk, but he was the world no.1, and after Jordan Pickford almost ended his career, Liverpool were playing then with maybe the world no.9 and 11, who were all on the same wavelength after years together; and then maybe the world #40; and now they’re playing with the world #157 and #373, who have zero shared understanding.)

Averaging eight players absent per game this season, this has very little to do with “just” van Dijk, even if he’s been sorely missed at times.

And while (as someone who hasn’t been able to do any sport for 22 years due to disabling illness, rather than the loss of a limb) I’m not making light of those athletes who lose legs (indeed, whose incredible resilience is worth remarking upon) – it’s a clear metaphor for how the human leg is ideal for a world-class sprinter; the carbon fibre blade is a superb alternative, but has drawbacks, especially when it’s first being fitted and getting used to; but a wooden leg may look okay when you’re wearing trousers, and keep you from falling over, but is fuck-all use for sprinting. It’s better than trying to run with just one leg (i.e. hopping), but only marginally.

And this season, if Liverpool were this metaphorical one-legged sprinter forced to find increasingly unsuitable solutions in order to muddle by, the wooden leg would be riddled with rot and woodworm.

This poor one-legged sprinter would be tying six tin cans together, and giving that a try; or searching the dumpsters of fashion shops for a mannequin off-cast. (A new carbon-fibre-reinforced polymer blade may be available within a year, but even then, it may take a lot of adjustments to make it fit properly, and it won’t be cheap. To fix his old one may take six months.)

Imagine Liverpool trying to win the Champions League in 2005 with Igor Biscan and Zak Whitbread as centre-backs. And then Biscan and Whitbread were to get injured, and David Raven and Salif Diao had to play there instead. At times it was bad enough with Djimi Traoré in the defence, and he wasn’t actually that bad half the time. Mauricio Pellegrino – an experienced, world-class defender when in his prime – came in past his prime, aged 33, and was pretty terrible (albeit he did help off the pitch).

Instead, most weeks it was Carragher and Sami Hyypia. Liverpool won the Champions League, in part because of Rafa Benítez’s brilliance with the mixed squad he inherited (but also by adding game-changers in Xabi Alonso and Luis Garcia), but also because of a world-class spine (apart from at centre-forward) that, as well as being elite, had been together for years: the vital “central square” of Hyypia, Carragher, Gerrard and Hamann each had at least six years at the club. You can’t buy that kind of understanding. Alonso was a rare gem who slipped seamlessly in, but into an area of the team that was well established and already elite.

That team had injuries too (and Djibril Cissé could literally have lost his leg from the first of not one but two compound fractures he’d suffer while with the Reds; Harry Kewell was top-class but injury prone), but not a glut in one key area of the pitch. Alonso had his ankle broken by Frank Lampard at New Year, but he was back by the quarterfinals, just in time to make a difference.

I’ve used other examples in recent weeks, but think of that midfield: Biscan, terribly limited overall, stood in very well at times during Alonso’s absence, but had Steven Gerrard, Alonso and Didi Hamman been ruled out – for the rest of the season! – even before the halfway point, the Reds would not have got to the quarterfinals, let alone won the thing. It would have been impossible, even if everyone else was fit.

Liverpool that season with Biscan, Diao and Darren Potter as the midfield three wins the Champions League? Not a chance in hell. No matter how great a tactician Benítez was at the time, or how solid the defence was; that’s game-over.

(Incidentally, both Carragher and Danny Murphy said that the game was already over at 1-0 to Everton when the crazy penalty was given, and so it didn’t really matter. So, Liverpool can score three second-half goals in Istanbul against the best team in the world at the time, but 10 minutes plus stoppage to get a single goal to equalise at Anfield against the same manager’s inferior side is now like being dead and buried? I agree that it didn’t feel like Liverpool were going to score yesterday, because of the lack of confidence in front of goal, but that doesn’t mean they would not have done so, even if only by luck. Being gifted a penalty would have been nice, for starters; but ludicrously for an elite team that does most of the attacking in games, Liverpool have now conceded 50% more penalties this season than they’ve won, and half of those given against them have ranged from debatable to scandalous. Almost all have cost points, or the chance of equalisers and winners. The Reds conceded one penalty last season, and it’s nine already this season. I’d say that just four were stonewall.)

Liverpool have a much better team and squad right now than in 2005, but take 8-10 players out of that squad – including several of its best players – and, just like any squad, it gets a lot worse. As I keep saying, the subs become the starters, and the U23 team become the subs. In some positions, the U23 team are becoming the starters, too.

Liverpool’s tallest established first-team outfield players going into this season were 6’5″, 6’4″, 6’3″, 6’2″ and 6’0″. Four of the five would start games if fit. They are elite players: big and strong, but superb footballers.

That would give Liverpool an immense physical platform, as it had in the past two seasons. No one could bully Liverpool, or beat them in the air. They were elite, and they were tall, and they were fast, and opponents feared them. They’d match you if you wanted to make it a fight, or out-head you in the air. There were no weaknesses, no achilles heels. Liverpool could play any type of game, and win.

After 20 minutes against Everton – who fielded several giants, and then brought on three even bigger giants – none of that Reds quintet were on the pitch (whilst a leader like James Milner was also out injured).

Three of them had already been ruled out for the season before the halfway point. Again, it’s not just van Dijk, but Matip and Gomez, and also Fabinho and now Henderson.

In their place was a 23-year-old with no top-league experience before this season (but the only tall player left, bar the very young and raw Rhys Williams), and a 20-year-old playing his third game since arriving a fortnight ago, and who, at 6’1″, is below-average in height for the position, which these days is about 6’2″-6’3″ (but he is a fraction taller than Jordan Henderson).

As I said several times even before any centre-backs were signed this winter: DO NOT EXPECT THEM TO SETTLE QUICKLY, as it’s nigh-on impossible. It almost never happens, especially if they don’t have a six-week preseason to settle-in and work on team shape and patterns of play, as well as the team bonding that occurs on those trips.

It’s so much harder midseason, and harder still in a team under pressure, lacking its leaders who can help you along. Communication and understanding takes many months of training and playing together to build up, bit by bit. Of course they won’t be in a brilliant line all the time in the back four, as back four work takes months and months of work, each season. And that requires training time, and there’s been precious little of that this season.

Of course a new young defender who was in Germany a week earlier wouldn’t know that his goalkeeper at Liverpool was going to come 40 yards from his goal to clear up when he possibly didn’t need to.

(Had Ozan Kabak played for years with Alisson – or even just six months – he would know how unusually high Alisson sweeps; and where, if it was Matip, Gomez or van Dijk, the keeper probably knows them well enough to just let them deal with it. Clearly neither Alisson nor Kabak knew what the other was going to do, and this is what I said you will almost certainly get. Equally, the alternative was to not sign anyone and play more midfielders, or 7th-choice defenders. It’s almost a no-win situation, as a 20-year-old Turkish lad was not going to be fully established and settled within mere weeks, and now the critics are out with their pitchforks. I’m sure I don’t need to remind Jamie Carragher how utterly awful he was as a young centre-back – absolutely all over the place, to the point where he had to be shunted to full-back to save both himself and the team – before he returned to the position in his mid-20s a much better all-round player, now full of experience, strength and guile; and after years where I’d defended him because he was a young player – in the days when I just used to discuss Liverpool on a private forum – he became a genuine club legend, who defended with nous and passion. But no one should forget how bad he was when he was Kabak’s age, and when he was not new to England, new to the league or new to the club).

Last season, four of the five I mentioned (the five players who are 6’5″, 6’4″, 6’3″, 6’2″ and 6’0″) were amongst the top 25 players in the Premier League for aerial duels won, with Matip ranked #1, having won a stunning 90% (40 out of 45 aerial duels) and van Dijk in his usual place in the top ten, where every year he ranged from 70%-80% won. That’s the top 25, out of hundreds and hundreds of players in the Premier League.

These absent Liverpool players are not just “good” in the air: they are about as good as anyone in world football. And van Dijk didn’t just win headers – he absolutely powered them away, or at the opposition goal. He is 6’4″, but can also jump as well as anyone in the game.

This year, Liverpool’s players all rank really low down, as they are on average much smaller, and any taller ones who do play have to mark – or get marked by – several far taller players. When it was just down to Matip, he was easier to mark from corners with no van Dijk, although he still scored and assisted from them.

I keep stressing this, but Liverpool have gone from the best aerial team in England – where some other clubs focus only on aerial football – to the worst.

Why?

All of the best aerial players are injured (just as Liverpool are not as quick without their quickest players). It’s not fucking rocket science.

The amazing delivery is often still there; the tall players are not.

Are Thiago, Salah and Shaqiri going to score many headers directly from corners? Salah got one against Palace, but only after Matip – to whom the Palace defenders were drawn but could still not match in the air – headed it to him, a few yards out, for a simple headed goal. Mané might get one or two, if he finds space because everyone else is marked, but he hasn’t been scoring from set-pieces when the bigger guys are absent. Otherwise, what?

Phillips (who was dreadful away at Newcastle, but has been very solid – if unspectacular – since) is tall, and can head a clearances away with real determination, but he’s never scored a goal or got a headed assist in his life. (Weirdly, in over 700 games, Carragher himself scored just five goals, and no more than three could have been headers, given that I can remember two he scored with his feet. Yet he was very good in the air defensively. Maybe he was more like Gomez, and less like van Dijk and Matip.)

Liverpool now have just one set-piece goal in the 19 games (Premier League and Champions League) played without both Virgil van Dijk and Joel Matip since the August of 2018, and almost all of those games have been this season; and obviously all of those have been when the team has struggled since the winter started, and when both players were injured.

At the current rate, Liverpool are losing close to FIFTEEN set-piece league goals this season.

FIFTEEN!

Think about that, and how many points that would be worth; how many games that could change, with more goals to follow if they broke the deadlock. Think about how many low-block teams, who concede tons of corners, could be broken down. Indeed, for two seasons, were broken down by all those set-piece goals.

TWENTY set-piece goals were scored in the league by the Reds last season; since all the centre-backs got injured, it’s been just one, and the other five set-piece goals scored were when van Dijk and/or Matip were in the team, with two coming on the opening day in one of their rare starts together in 2020/21. Fabinho and Henderson in the midfield, finding space when van Dijk and Matip are marked, would also be another set-piece threat. Roberto Firmino becomes more of a threat, at 5’11”, if he’s the 6th-tallest player in the Liverpool team, not the 2nd-tallest. Sadio Mané can sneak in at the near post or far post.

Again, Liverpool scored a set-piece goal every three games when van Dijk and Matip were partnered together since August 2018, and one every four games with Matip and a different partner. Now it’s 1-in-19. That in itself is a drop-off between title-challenging form and toothlessness in goalscoring.

It’s also a kind of madness to point out that Liverpool lack leaders when most of the leaders are out injured. Milner, Henderson, van Dijk, Matip, Fabinho and others are all leaders, but currently playing “pass the medicine ball” at Kirkby.

Or that the Reds lack centre-backs who are good enough, when most of the centre-backs – from 1st choice to 5th choice, out of the ones who hadn’t just arrived – are injured.

Or that the Reds lack quality midfielders, when so many have been injured, and others are covering for the unprecedented situation at the back.

Or that the defence lacks pace, when the quickest defenders (and indeed, as well as one of the quick and prolific attackers) are out injured.

Or to focus on the strikers, when goals from other areas have been hit harder.

Indeed, I’ve seen people say that Liverpool should have bought a player to challenge the front three, who have gone stale – which is wrong on two counts.

Was that not Diogo Jota, who was scoring a goal at the best rate of just about any player in England before he got injured?

And overall this season, the front three have done well (41 goals, in addition to Jota’s nine). It’s just been recently, at home, after a similarly barren spell away from home, after the freakish 7-0 win at Palace, that the finishing has gone to pot.

Rookie Minutes

This was another game with a lot of minutes played by two players who had virtually no Premier League (or any top-level major league) experience going into the season.

This was another game with a lot of minutes played by two players who had virtually no Premier League (or any top-level major league) experience going into the season.

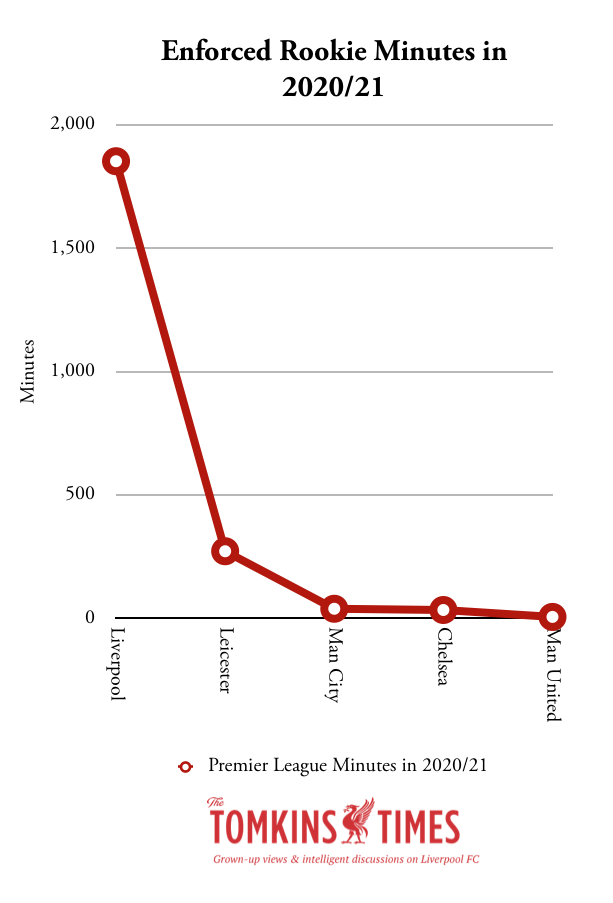

The contrast with all the other big clubs is stark. See last week’s piece, which I link to at the end of this article, which is some in-depth analysis we will be updating on a regular basis as the data changes, and as new things arise. That graph (last week’s version is published here) will only look worse once updated, as will the set-piece one and the injuries one.

Liverpool haven’t had to play any rookies as forwards this season. But they have in midfield, all across the defence, and in goal. Stability of selection has been impossible. Rotation has been impossible.

Finishing Gremlins

Finishing in football is often pretty random. We all know it can be streaky, and so to write off any of the front three at their ages is ludicrous.

At times they haven’t played as well as they can, and not all three are necessarily ruthless finishers in the classic mould, but the non-penalty goal drought at Anfield is simply a freakish occurrence. (And it’s been just one penalty to Liverpool in that time, given by the only ref who is worth bothering with, who gives decisions for and against Liverpool, and not just against Liverpool. Yet in this 2021 goal drought at Anfield, Burnley, Manchester City and Everton have all been given penalties. Two of them were clear-cut; one was a joke. Liverpool should have had at least two, if not three or four in that time.)

You can’t force finishing. You can’t make players finish better by putting more pressure on them. It needs to be a mix of focus and relaxation. So many strikers have streaky periods. Timo Werner just went about 20 games without a goal, and he was a player who, at £50m, was “half price”, as his market value a year ago was £100m. He’s new to England, and so he needs to be cut some slack, but he started on fire. Next, he couldn’t hit a barn door, after a career spent getting goals.

I said at the time – lest people think I’m just an apologist – that no way did Liverpool “deserve” to beat Crystal Palace 7-0. It was freakish. Liverpool had eight chances and scored seven goals. 4-1 would have felt fair. Yes, it was joyous to win 7-0, and the goals and the finishing were sublime, but it was a much tighter game on the balance of play.

So we have to acknowledge that the scoreline flatters the Reds when it flatters the Reds.

It’s the same as when you “deserve” points and don’t get them, like in some recent games. Had Liverpool won 3-0 at Palace, and then “saved” the other four goals for the games against Burnley, Brighton and Everton, when the big chances were there to be taken, it would have been so different in terms of results, but no different in terms of overall team performance or finishing (in totality); just the distribution of the same number of goals. But you can’t save your goals.

At Anfield, Liverpool’s forwards are having what is collectively known as a “Peter Crouch”.

Crouch eventually scored 22 goals for England in just 42 games, and scored over 200 goals in club football. Obviously he wasn’t a “pure” goalscorer: he was roughly a 1-in-3 striker, who laid on assists with his height and his clever flicks, chest-offs and neat skills.

Yet after he joined the Reds he went over 24 playing-hours without a goal: 19 matches, spanning four months, or almost half a season.

He broke his duck with a ludicrously deflected goal (see last week’s piece for more on the randomness of deflected goals) that after the game ended up being taken away from him anyway; but crucially, at the time, he thought it was his goal and his hell was over, and so then, finally relaxed, he promptly added another in the same game. Twelve more goals followed in the second half of the season. From none in 19 games to 13 in the next 30. That is an utterly crazy distribution, but that’s football. (Weirdly, it mirrors, in reverse, the Reds’ goalscoring from set-pieces as discussed earlier.)

Andrew Beasley will be looking at this more in a superb subscriber-only piece on taking clear-cut chances this week, but the odds of Liverpool missing so many clear-cut chances (as well as all the other shots, bar Mo Salah’s penalty against Man City) are astronomical.

The odds will be in the range of many thousands-to-one, just as it would have been for Crouch to go 24 on-field hours without a goal from all the opportunities he had.

Now, Roberto Firmino is more of a Crouch in that he’ll average a goal every three games (84 in 279 games for Liverpool) – because his game is about linking play, making space, pressing, and providing assists, rather than being the primary goalscorer; and Bobby is off form in front of goal. Sadio Mané is closer to 1-in-2 (92 from 202), and Mo Salah is far better than 1-in-2 (118 in 187 games) – albeit with around 20 penalties once he finally took over from James Milner.

That’s nearly 300 goals between the trio, in just 4-5 years at Liverpool. Had Milner not taken the penalties for the first few years, they could easily be over 300 goals by now.

Now, if they have a terribly barren streak, aged 28-29, are they washed up? Really?

Or were they never any good to start with?

Clearly not. They were the best front three in world football, according to many pundits.

Weirdly, the goalless streak began in games that were both home and away, but then they started to relax away from home, once Salah scored in the cup at Old Trafford, and they are now taking their big chances away from home at a more normal rate (i.e. not taking every single one, but converting enough). The Reds got two at United, three at Spurs, three at West Ham, one at Leicester and two against Leipzig. Away, with the players relaxed, the goals are flowing – 11 goals at a time when they’ve scored just one (a penalty) at home.

At home they are snatching at chances, and every game it gets worse; and when they do connect brilliantly, which is intermittently, the visiting keepers are making some amazing saves.

Again, this is not me sugarcoating anything. Anyone who thinks that is being too simplistic.

You have to look at your good luck when things are going well, and your bad luck when things are not. The better your luck goes, the easier it can become; the worse your luck goes, the harder it gets. Pressures can be eased by good fortune, and increased by bad fortune.

Liverpool were sensational in getting 97 and 99 points, winning the league and the Champions League, but every few games there would have been some favourable luck; or the team was playing so well – with virtually no injuries – that bad luck didn’t affect the game, or bad decisions were at less influential times.

You don’t have near-faultless seasons without also often having the bounce of the ball at key moments, or your keeper making big saves, or your strikers scoring at just the right times.

Liverpool had the reverse luck last winter to that now experienced at Anfield: over FIFTY attempts against Liverpool across a string of games resulted in ZERO goals conceded as 2019 turned into 2020, with big chances missed week after week by opposition players, or saves – difficult and easy – made by Alisson.

That was a super-hot streak of good luck (and great goalkeeping). This is a super-cold streak of bad luck and great opposition goalkeeping (and in some cases, at the other end, uncharacteristic bad goalkeeping).

Because, finishing often involves a lot of luck. You can score lucky goals when you do nothing right – one can hit you in the back of the head when you’re not even looking (a bit like a Dominic Calvert-Lewin knee); and you can be denied world-class efforts, where you do nothing wrong. You can score a legitimate goal and it be incorrectly ruled out, and you have done nothing wrong, or score an offside goal and it be allowed to stand. You can be be given penalties for nothing, or see penalties given against you for nothing. That’s why the officiating is so important, particularly big decisions at big moments in matches.

One thing I know a bit about is finishing. Although I played as a semi-pro (for a club formed 150+ years ago, in the 1860s, some 24 years before Liverpool FC existed), it was only for one season, due to my health problems starting to become more noticeable (and I finally got my own season ticket for Anfield, having been sharing use of a friend’s dad’s, and chose to use that instead).

I’ve told these stories before, but new readers might not have read about them. I was the new guy, shunted from position to position, and only occasionally getting games as a striker – I scored a first-half hat-trick in preseason in my usual role up front, but was moved to left-midfield at half-time and stayed there for a while. I had a game up front, but froze when the real games started, and was moved to right and left midfield, then back up front for a game or two. I played in central midfield for a couple of games.

At first, whenever I played up front, I couldn’t find the back of the net, apart from the occasional scruffy goal, albeit one of those was as a wing-back after we switched formations (which was the most knackering position to play). While this is not elite football I’m talking about, I constantly analysed things. Every time I stepped up to a new level as a player, I had to work new things out. I always apply that same logic to my analysis of football now.

I was under pressure. I didn’t feel like I belonged, even though I’d always scored a ton of goals at school level, county level, university 1st-team football leagues, and the top Sunday League divisions at a time when there were 7 or 8 divisions (one season I got 48 goals in 27 games, a club record). But as a semi-pro I was snatching at chances. In an FA Cup game early in the season I missed some easy chances that, if playing against the same players on a Sunday morning (where some of the same players also played), I’d have taken with my eyes closed.

Then, after returning from illness over the winter – consecutive viral infections – I returned to play in a local derby watched by hundreds of paying fans. It was my second game back, and I’d missed a big chance in my first game back.

Anyway, in this derby the goalkeeper came rushing out at 1-1 near the end of the game and I had no option but to lob the bouncing ball over him. I had no time to think – it was the only solution with the ball bouncing, and it went up and … in. I felt relieved, but I wasn’t exactly full of confidence. I’d got a goal here and there before, but still never felt settled.

Then, a few minutes later as the game moved towards the 90-minute mark, I intercepted the ball on the halfway line and my pace took me beyond all the opposition defenders on the inside-left channel, with a perfect touch. I knew I had bags of time, as I was as quick as anyone at that level, and I was clean through, down the inside-left channel.

Yet my next touch was far too heavy, so the keeper, sensing his chance, came flying out.

Again, he made up my mind for me, and I knew I just had to beat him to the ball, and how quickly I did so would dictate the finish; I got there just in time, and with my right foot curled the ball past him (weirdly, a bit like Divock Origi’s attempt that hit the bar against Burnley), and it went into the far top corner. This time, even though my first touch had still been ropey, I sensed I would score as soon as I took the shot – the pressure was not totally off (I hadn’t proved to myself that I belonged at that level), but I was fairly relaxed when I hit the ball. However, I knew that had the keeper stayed closer to his goal, and I had to take more touches having just taken a really loose touch, I might have screwed it up.

As ever, when you’re not full of confidence you work better when there’s less time, and you rely on instinct. We won 3-1.

Then, fairly early in the next game away at the league leaders, I took the ball down on my chest about 35 yards from goal, let it bounce onto my thigh, and then volleyed it into the top corner. Bar some mazy dribbles, where constant skill was required, it was probably the best goal I ever scored at any level, and it was at the highest level I ever played. It would not have been something I’d even have attempted but for the two goals at the end of the previous game.

It was almost like an out-of-body experience, as I had no conscious noise in my head: pure silence and flow, for the first time at that level. I can still feel my body, with not even the slightest hint of tension that can make muscles more rigid and cause slight – or serious – interference with the movements. I was totally “loose”. Utterly unhurried, even though there were defenders close by.

I can still sense the silence in my head, and the way I could foresee what I was going to do before I even did it, without consciously thinking those thoughts. They almost coexisted in a different part of my brain to the silence: it was wordless, with neither doubts nor hopes. It’s what the state of “flow” feels like. I knew it was in as soon as it left my boot, yet looking back, it felt like I knew it was in before I even took the shot.

But later in the season – after yet another viral infection laid me low (I was missing more and more games) – I had a game where I missed a few chances again, felt weak and low on energy, and my confidence vanished. I was no longer in a state of flow; my head was full of noise. I would beat myself up for days about bad misses. In the last few games I was terrible again.

Had I not had to give up playing at that level in 1997 (and in 1999, aged 28, give up all sport when diagnosed with M.E.*), I believe I would have started the next season feeling like I belonged at that level – got back to being sharp and confident – and had I not been ill, I could have moved up the leagues; but done so in gradual stepping phases, adapting then moving up, until I found my limit.

(* M.E. is a kind of constant, incurable post-viral systems meltdown similar to what we are now seeing with Long Covid, where so many of the body’s key functions are disrupted. In December 1990 I almost died of an asthma attack, and needed all kinds of interventions to be kept alive, and from that point, aged 19 and at the time it occurred, supremely fit, I could never get fully fit ever again – only partially fit. From that point on I had extreme fatigue after games, that as the ’90s wore on it went from lasting 3-4 hours to 3-4 days, and all kinds of things like blurred vision, migraines, giddiness, agonising muscle pains, inability to climb stairs, and various other issues that always followed playing football. I feel that this is worth mentioning again, given that M.E. research is now being tied in with Covid research, and it doesn’t hurt to raise awareness, without any sense of self-pity – I have adapted my life, and found new opportunities, even if I will always miss playing football. It’s also a constant reminder to me about how adversity – while you don’t necessarily want to go looking for it – builds character, teaches wisdom, and how whatever doesn’t kill you really will often make you stronger. That clearly can also apply to Liverpool, after this season.)

Had I not been ill, and done a second season as a semi-pro, the issue would be more about form – as it was at the end of the season – rather than “can I do this?” I knew by then that I could do it, at that level.

My point here is that Salah, Mané and Firmino can “do this”. They know they can.

Despite none really getting going until they were in their 20s – all three were late bloomers – they have a mind-blowing 294 goals for Liverpool and almost 600 for all their clubs and countries (584), despite not yet being in their 30s.

So, when players as prolific (if not “ruthless”) as this miss clear-cut chance after clear-cut chance, it’s not that they are bad strikers. Far from it. It’s not that the team is playing badly, either, if you create the chances to win games; finishing is almost a separate debate to how a team plays, even if it is still part of the performance.

It’s how football works. Usually at Liverpool, one would have a bit of a barren spell but the other would be on fire. If two were off form, the other would bag a hat-trick.

None of them are like, say, Dominic Solanke a couple of years back, who had been very prolific at youth levels but who had never quite clicked at senior level. You couldn’t blame Solanke, as he tried his best, but equally, he wasn’t someone you’d expect to score 20 goals or more in a season, or to take a string of big chances. He got one goal in about 25 games.

The current trio are proven top-level goalscorers. But all proven goalscorers have more prolific periods and less prolific periods. All experience droughts. If they overlap you might have problems, but you can’t put force players to score. They will always practice finishing in training, but it often needs a bit of luck to get out of a personal slump.

Add in the lack of goals from midfield (because Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain is far too rusty and appeared woefully off form after six months out, and Naby Keita is not quite ready after missing a ton of games), and the lack of goals from van Dijk and Matip (and set-pieces in general, to which they contribute to goals, even if not scoring), and there’s more pressure on the strikers at this moment – at a time when they are misfiring, and mentally blocked, at Anfield.

Add that the team is constantly changing at the back, and in midfield, and in recent games, Alisson made some uncharacteristic and very costly mistakes, the pressure on the strikers is just getting greater. If your team is keeping clean sheets, your strikers are freed from a lot of that pressure; just as if your strikers are scoring goals, your defence and goalkeeper are under less pressure. A team is a holistic enterprise: it defends together and attacks together, and a collapse of confidence in one area can spread to another. They are not totally separate units like unconnected islands.

In addition, Nick Pope, Sam Johnstone and Jordan Pickford all had exceptional games at Anfield in this run. So it’s not just been about bad finishing.

Liverpool’s finishing has often been nervy, but on the efforts they’ve caught just right the keeper has denied them. Again, that happens. How an opposition keeper plays against you is also often random; those same goalkeepers gifted goals to some of Liverpool’s title rivals at a time when Liverpool were still in the title race. Those keepers have helped take Liverpool out of the title race, whereas in other seasons keepers helped put Liverpool back into the title race.

Go back a year, as I said, and opposition teams were missing all their big chances against Liverpool, and Alisson was in exceptional form.

But go back two seasons, and Pickford was just one of half-a-dozen goalkeepers who absolutely gifted Liverpool vital goals. They were dropping them into their own net, punching them in, throwing them in, hauling down Liverpool players. Tight games were turned in the Reds’ favour due to a series of goalkeeping errors. Back then, neutrals said Liverpool were “lucky”.

Three seasons, and three different Black Swan sequences in the goalmouths. Two benefitted Liverpool, in the seasons when the Reds finished with 97 and 99 points; one is working against the Reds, and the team, riddled with injuries, is sliding towards mid-table having been top in December.

If you add Alisson’s own bizarre mistakes, in costing three key goals in two big games within a week, you can say that it’s freakish, statistically, at both ends of the pitch in 2021. Just as you can’t force a striker to score a goal, you can’t stop keepers making mistakes; they happen in the moment, and as with strikers missing chances, often one mistake leads to another mistake, as it starts to play on the mind. It becomes a negative spiral. It can be overcome, but it often takes time to settle back down.

Liverpool’s play in the middle of the park is still good. All the stats back this up. They boss possession, and are creating big chances. They win a ton of corners. But why can’t they score from these set-pieces? (You know the answer.)

This is a great team, with a great manager, great coaching staff and great backroom and recruitment/analytics staff – all have proven as much – run by owners who have taken both the Red Sox and Liverpool back to the top after many decades of misery before they took over. This is a tough season, for myriad reasons, and it may get worse, as any negative feedback loop or vicious cycle can. But any kind of summer reset – switching off, to recharge and then refocus – and with the key players back from injury, can easily change things, just as Man City did this season, after far fewer injury issues last season. Hopefully the Reds can salvage something from this nightmare of a campaign (and reaching the quarterfinals of the Champions League would be a start), but the baby must not be thrown out with the bathwater.

Anyway, while this is now itself a fairly lengthy article, last week’s in-depth piece (that covered more issues) can be found at the link below, which we will continue to update, as a resource for all the things that have gone wrong, many of which are just the way the cookie crumbles sometimes.

(And that’s without that piece looking at things like the lack of a crowd – Liverpool are losing soulless games at home under Klopp after three full years undefeated with full crowds in the stadium; or the lack of a proper “Kloppian” preseason, that hard-pressing football requires; or the refereeing and VAR madness, that we will feature in its own piece this week.)

Later this week we will be assessing the VAR and refereeing madness of the season.

Please note: we are giving away these “free” articles at the moment (even though the site costs several thousands of pounds per month to host and staff), to help try and provide perspective to all fans who are interested in context and extenuating circumstances, and who are smart enough to know that an “excuse” is usually something mild and often irrelevant, and thus, not applicable here. A flat tyre is not an “excuse” if you are late to work, because you had to change it for the spare and it took a lot of time; being stuck in a tunnel on a broken-down train for hours, likewise (you can’t get off, and you can’t fix the train yourself); being hit by a bus is even less of an “excuse”.

If you are either smart enough to add to our knowledge pool, or eager enough to learn, then please subscribe for £5 a month (but if you are some know-it-all blowhard, please do not). Either way, feel free to share these free pieces if you think they add to the general debate, and if people elsewhere on the internet disagree with them, or even hate them, that’s their prerogative. We can live with that.

But remember – it’s harder than ever to be intelligent, thoughtful and to look at complex situations in any depth, and with any nuance.

I’d urge people not to pander to the knee-jerk instant-outrage that much of the internet and media thrives upon; the hot-takes during and straight after games that are often just hot air. (It doesn’t help that so many people in the media spend so much time on Twitter, and lose their perspective when getting drawn into constant sniping and snarking that it creates, that then gets carried back into the media, as if everyone is just responding to, or trying to outwit, Twitter trolls the entire time.)

Or if you do, don’t bring it onto this site, as we’ve never done that. Similarly, we do not run advertising – and haven’t for over a decade now. We rely on people paying to read our work, and to give themselves the chance to join in the debate, as long as they don’t act like TTT is Twitter and lose that chance.