In the seven Premier League seasons prior to 2019/20, there were over 600 penalties awarded, and at The Tomkins Times we thought it was worth looking into each and every one, in detail, to see if there was some kind of pattern of bias from referees.

This is a study of all teams, all players and all penalties. While I will also focus on Liverpool in the opening part of the article, not least due to the origins of this research (and this is after all an LFC-centric site), this is not a Liverpool-specific piece, and hopefully not Liverpool-biased in that it’s purely data driven.

However, from what we can see, the results of a potential bias against foreign players are pretty mind-blowing and according to a university professor I ran the figures by (because I’m not smart enough on my own), “highly statistically significant”.

The issue first arose when I realised (as covered on this site in the last year or so) that, since 2002, Liverpool as a team win a greater number of penalties the greater the number of British players in the side, no matter how good the team is (when compared to actual league position), and that British players win a greater percentage of those penalties.

This seemed very odd to me, along with the fact that Liverpool increasingly win most of their penalties away from Anfield, despite having better attacking “metrics” at home; and that the Kop end is weirdly a no-go zone for the Reds’ penalties domestically, perhaps in response to the old myth (perpetuated in England) that Liverpool get too many penalties in front of the Kop. Look at the reaction from the media, Twitter and opposition managers the next time Liverpool win a penalty at the Kop end and it will almost certainly centre around Liverpool “always” getting penalties at that end, despite them being counterintuitively rare. (Confirmation bias only sees what it wants to see; data tells you the true story.) Liverpool get far more penalties in Europe at Anfield than in the Premier League – during one several-year period the Reds were awarded one four times as frequently in European competition than domestically, and it’s not that Liverpool were getting a penalty every game in those Europa League and Champions League matches.

Also, another clear anomaly is that all the other big clubs get a normal percentage of their league penalties at home, which for all clubs across the entire Premier League era remains around 66%, or two-thirds. By contrast, Liverpool get a normal number (in overall quantity) of away penalties for their quality as a top six side, but an abnormally low number of home penalties, and rank 11th in the last five years for league penalties overall. The top penalty-winning sides of the past five years are, in order: Leicester City, Crystal Palace, Manchester City, Brighton & Hove Albion, Bournemouth and Everton. That, clearly, is bonkers. (Also, Man United have now won 14 penalties in their last 40 league games; for Liverpool, who won far more points in that time, it’s just eight. But this may be a shorter term blip.)

It remains true that Spurs have won more Premier League Kop-end penalties at Anfield than Liverpool since 2017, and also, the Kop-end penalty in May 2017 that James Milner missed against Southampton was the last handball penalty awarded to the Reds in the league, almost two-and-a-half years ago. Handball itself is such a weird, subjective ruling that refs could give or ignore them and justify it either way; although the Reds did get a fortunate – but clear – handball in Madrid in June. That, of course, was not at Anfield, nor in the league. (Edit: of course, the handball rule has been changed this season, so it’ll be interesting to monitor the effects it has.)

Another weird thing that the research threw up (briefly covered above) was how mid-table teams tend to win the most penalties, followed by top six teams, followed, in accurate stepped decreasing order, by the teams that finish below mid-table all the way down to the team that finishes bottom, which on average wins the fewest.

So there are lots of weird anomalies that seem to be the result of “pre-think”, the prejudicial attitudes of referees. Expect to see something, and you will be more likely to see it. Think that you won’t see something, or you are simply not expecting to see something, and you’re less likely to see it. (See the famed “inattentional blindness” gorilla experiment.)

Going back to the 2002-to-present-day data for Liverpool, I wondered why players like Steven Gerrard, Raheem Sterling, Michael Owen and even Jon Flanagan won penalties more frequently than players like Sadio Mané and Roberto Firmino. (Mo Salah was also unfairly treated in his first 18 months at Liverpool, until he started winning “too many” penalties last winter, at which point he was deemed to “dive”; something that seems less of a problem when it’s Jamie Vardy, Raheem Sterling or Harry Kane, and most recently Tammy Abraham in the European Super Cup, where all such players are said to simply “go down a bit easily” when there’s no contact.)

The correlation on Liverpool seemed clear – particularly on the relationship to British players (managed by British bosses) winning league penalties at a far greater rate. However, the data set is for just one club, and even over a 17-year-period, was “just” 100 penalties exactly; a reasonably high figure, but a bigger dataset would be more revealing.

So I enlisted the help of several volunteers and together we researched each and every penalty awarded in the hundreds and hundreds of Premier League games since 2012, and collated the full details in a database: which player won it, which player conceded it, whether it was a handball or a foul, and more importantly, the nationalities of those involved. We also listed the referees, whether it was home or away, and a few more details. In one of the fields we included a line from one of the main newspapers, Sky Sports or the BBC describing the incident, so that it was their description, not ours.

The verdict? Foreign players appear to be shafted.

Define Foreign

Okay, now defining people in 2019 is not as easy as it once was; labels can be powerful, and there’s a lot of talk now about what people “identify as”, which may be contrary to what we, as observers, would judge them as. So the definitions we use may not be perfect, but they are consistently applied based on two key factors: country of birth, and when they entered the British football system.

For the purposes of this study we divided everyone into two distinct groups: British/Irish “raised” (i.e. products of the geographical area’s youth systems), and everyone else (“foreign”). Some of these foreign players may now be nationalised as UK residents and hold British passports. Others were born in the UK, but due to a parent or grandparent now may play for an entire other country.

“British/Irish raised”, for the purposes of this study, means players spent at least some time in the British or Irish school systems. So they moved to the geographical British Isles before the age of 16, even if they didn’t represent those home countries. (For the purposes of this study I will refer to British players to mean “British Isles geographically”, just because the nature of football is basically very similar, with a large degree of interchange between them all. Ireland is obviously distinct from Britain in many ways, but the football melting pot puts everyone together.)

So, someone like Wilfred Zaha is now an Ivory Coast international, but played full international games for England in the past. He moved to England at the age of four. So the hypothesis is that he is seen by referees (consciously or subconsciously) as being an “English guy”, in contrast to, say, Naby Keita, who can surely only be seen by them as African (especially as he didn’t really speak English last season).

Zaha, and Sterling – who arrived in the UK from Jamaica aged five – win penalties at a rate that no non-white foreign player does. So, without delving into the complexity of race, the issue feels more about a cultural bias than an issue of skin colour. (It’s one thing to determine where someone was born and raised, but determining someone’s race can be far more complex.)

The assumption on our part is that the “foreigner” – which we obviously don’t use as a pejorative term but where we all know it can be – is perhaps seen as more likely to dive, or possibly, by having no verbal relationship with the referee, is not given the benefit of the doubt, with no type of friendly badinage exchanged before, during and after the game. The hunch is that England internationals get preferential treatment, unless they are seen as having clear disciplinary issues.

(Everyone could see that Wayne Rooney was a hothead with regular disciplinary issues, so if he kicked someone he’d usually get punished in a way that, going back years, Alan Shearer would not. This may of course just be an image issue. The benefit of the doubt is an interesting concept as it is prejudicial by its very nature; and just one example of how referees – who are liable to all human biases like the rest of us – don’t necessarily give what they see – because what we see can be deceiving even in the most basic of senses – but what they think they see or what they want to see; or what they want to be seen as having seen, if that makes sense – so, to be seen to do the right thing even if it goes against what they actually witnessed.)

Obviously each penalty involves its own individual set of circumstances, and may have been a good call or a mistake. And each referee is an individual too; and even the same referee can be inconsistent, just as we can all have good and bad days. (Go look up the difference in punishments meted out by hungry and tired judges compared to fresh and well-fed judges. It’s terrifying.)

For the purposes of this study we excluded handballs, as they appear to be a totally inconsistent mess: some seasons there were more than three times as many awarded than others (19 in 2016/17, just six in 2017/18, then back up to 14 last season).

That left 536 penalties for the study, after excluding just a handful of penalties where it wasn’t clear who committed the foul, or involving players who moved to England at the age of 16 (and so they fit neither category, and where we installed a slight buffer zone of being in neither category, because you could argue that they could be in either category). And to be clearer, there were 536 penalties listed as won and just 534 listed as conceded, after the borderline players were removed from the equation, and because of instances where two players jointly conceded the penalty (and if they were from opposite groupings, cancelled each other out).

Across the seven seasons there are two categories for each campaign: penalties conceded, and penalties won. That means 14 sets of results.

Of these 14 categories, 12 saw British players do better than expected when compared against the minutes player, and only two saw foreign players do better than expected.

Expected Penalties

To know how to judge how many penalties each set of players “should” be winning and conceding it was vital to know the percentage of minutes played by those players.

However, to make the task more complicated, someone like Zaha would now be classified as an African player (as an Ivory Coast international who no longer plays for England) in most datasets, whereas in our study we’d already said he qualifies as homegrown. So we had to go through every single Premier League player since 2012 and manually assign them to one of the two groups, then look at how many minutes they played each and every season.

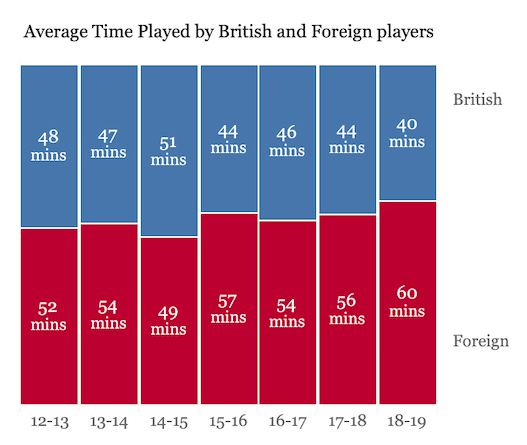

By our definitions, 45.5% of minutes in the last seven seasons were played by British/Irish players (including those who were part of our football structure before the age of 16 but now play for overseas nations, such as Zaha), and 54.5% foreign. Again, these figures are slightly different to other data you might see due to the different criteria for the reasons outlined.

On average, there has been a drop in British minutes, from a high of 50.8% in 2014/15 to a low of just 40% last season. Yet the percentage of penalties Brits win remains higher than expected, and the penalties they concede remains lower than expected.

271 penalties were won by British players, and just 263 by foreign players. This is not a huge difference, but it’s still more than expected for the Brits and less than expected for the non-Brits.

Professor Mike Begon of the University of Liverpool applied a chi-squared test to the results.

He explained:

“Statistical convention has it that results are significant if P<0.05 (less than 5% chance of such a result arising by chance), highly significant if P<0.01 and very highly significant if P<0.001 (chance of less than one in a thousand).”

And in this instance Mike said that the discrepancy was statistically significant, but not highly statistically significant. (However, it was close to being so.)

But then we get to the really weird results. Of the penalties conceded, a whopping 328 were by foreign players, and a measly 208 by Brits. Mike described these results as “highly significant”; which means a one-in-a-hundred likelihood of appearing by chance.

So, it seems that foreign players are treated unfairly in terms of winning penalties, and very unfairly in terms of conceding penalties.

As you can see below, the expected amount (E) almost always sits above the actual amount (T) for foreign penalties won, but almost always sits below for foreign penalties conceded. And obvious the reverse is true for the British/Irish players.

Why?

Of course, we could then argue that British players are better attackers and better defenders, ergo their superiority is reflected in the results.

But really, does anyone who actually watches football think that?

For starters, any non-EU player has to be deemed exceptional to even get a work permit (something that was never required of Paul Konchesky, unfortunately). People could rightfully counter that a lot of foreign players end up looking terrible, perhaps due to not being suited to English football, not speaking the language, being homesick, and so on. Foreign players certainly have more adapting to do than someone who grew up in our football and, of course, who knows how our referees interpret things.

(Which is why I think British players “flop” down as a dead weight rather than arch their backs when they dive. So that could play a big part, but then it’s actually in the conceding of penalties where foreign players seem more unfairly treated.)

However, to get a vague baseline of quality we looked at the top attacking players, statistically speaking, for the seven seasons in question; based on the combination of goals and assists. (This doesn’t necessarily suit the strengths of every attacking player, but goals + assists is still a pretty good basic rule of thumb.)

This resulted in 174 player seasons, with some players obviously appearing multiple times as they have been in the Premier League for some or all of those seasons (Sergio Aguero is included for all seven seasons, as a mark of his consistency, so he has seven player-seasons).

Yet of these 174 “players”, a paltry 28% were British. However, the British players, despite comprising 45.5% of the total playing time and posting just 28% of the elite numbers, won over 50% of the penalties.

And with British players conceding just 38.8% of the penalties since 2012, are we saying it’s because British defenders are better than Virgil van Dijk, Vincent Kompany, Laurent Koscielny, Toby Alderweireld, Jan Vertonghen, Aymeric Laporte, et al?

Weirdly, those guys are much more likely to concede penalties than one-man walking disaster zones like Phil Jones, or the persistent in-box fouler, Ashley Young (I know this is a bit of a dig at Man United, but Young’s reputation as an ex-winger and “nice guy”, seems to spare him from refs seeing his blatant fouls).

It’s harder to assess defenders individually in terms of statistics because a lot of what they do is unit-based. But it’s not clear that there are a ton of great British defenders in the league and far fewer elite foreign ones. If anything, the Premier League has the best British defenders, plus the best defenders from many of the best nations in the world, like Holland, France, Belgium and so on.

There may be other reasons for the clearly contrasting results, but in trying to be fair to referees, there aren’t too many more things we could come up with (let us know if we’ve missed anything obvious).

With the introduction of VAR we should see a levelling out of what seems like clear unfairness, assuming that the officials are not allowed to fudge bad decisions by saying “it was only half wrong, therefore the decision stands”.

And in a rare defence of Man City, I don’t see why VAR did not overrule Michael Oliver (otherwise the best ref by far, and, statistically, pretty much the only one who gives Liverpool big decisions at Anfield these days) missing the foul on Rodri in the first-half of the match against Spurs. My hope was that VAR would simply call attention to all clear penalties, no matter what the ref thought he saw, because he has 10 fewer angles than VAR and no slow-mo; and that was a clear penalty. VAR should be given the power to overrule a referee, and setting the bar as a “clear and obvious error” appears to be another way just to retain the status quo. But that’s another issue entirely.

Whatever happens, referees urgently need to be taught about all cognitive biases – or, no matter how well they know the laws of the game, they will never be able to apply them fairly. Reading the work of Daniel Kahneman should be as important as knowing the back-pass law.

At the very least, we can hope for some correction of what looks an undeniable – conscious or subconscious – bias on the part of referees against foreign players, and as such, we will revisit this issue at the end of the season, to see if there is any change. It may end up helping Liverpool, but of course, helping Man City too.

Researchers: David Whitmore, James Fleming, Matthew Beardmore, John Gordon, Tim Buckley, Daniel Rhodes, Paul Tomkins. Data viz by Robert Radburn.