I’ve heard it said – by Jonathan Wilson amongst others – that football managers usually only get a decade at the top. Indeed, I’d written a passage in my first book, back in 2005 (which at the time was about how Rafa Benítez was taking Liverpool into the modern age), discussing how the title-winners from the first three years of the ’90s – Kenny Dalglish (1990), George Graham (1991) and Howard Wilkinson (1992) – were by that point, a decade or so later, out of work; the point being that new men with new ideas come along, and shunt them out.

So, is the notion that managers get a decade at the top true? I thought it was worth further investigation. And while there are always exceptions to any rule (Alex Ferguson’s success spanned more than 20 seasons; Joe Fagan’s was a brief and brilliant flourish), it seems to hold some water.

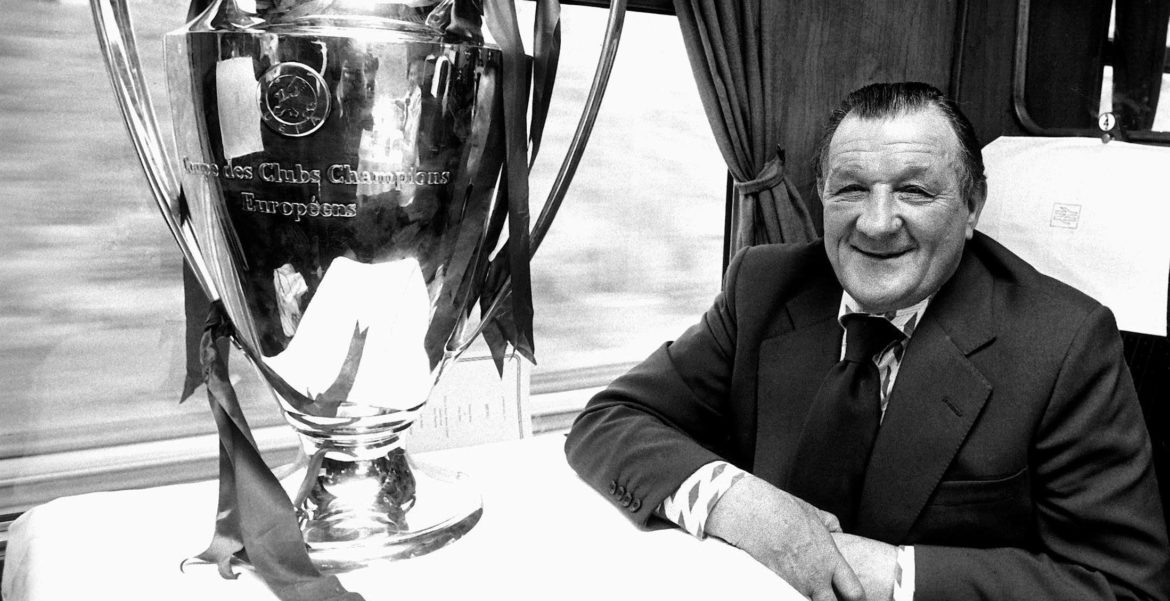

Bob Paisley, after a disappointing first season, won one of the two biggest trophies in each of the next eight years in a nine-year spell as boss – an unparalleled achievement, with not a single season between 1975 and 1983 where he didn’t win either the league or the European Cup. We’ll never know if he could have gone on longer, or if the magic touch would have faded; but I’d argue that no other manager in the history of football has come in, done what he did, and then got out, before the standards slipped even 1%.

Even Ferguson’s incredible success pivoted on the changing of assistant managers, with the input of fresh ideas; his longevity was unique, but he retained consistently strong financial backing (compared to, say, Arsene Wenger, and the fallaway in Arsenal’s finances with the new stadium), and in addition to the money, Ferguson’s inspired refreshing of his coaching staff kept him at the top.

For the purposes of this study I went through and found (hopefully) all of the most successful managers of the past 40 years, focusing purely on football within Europe, and then worked with my old school friend and current Tableau Zen Master, Robert Radburn, to create the visual which follows further down the page (which he will later share on his own site, along with part of this article; but for now, the bulk of the article – beyond this intro, my explanation of the graphic and the graphic itself – will be behind this site’s paywall.)

Please note: it’s easy when researching something like this to make it so big that you can’t actually complete the work, so you have to make decisions. I narrowed the search, and set specific criteria that not everyone will agree with (but you’re free to research and write your own articles…). I focused on the elite of European club football, and that means no inclusion of South American achievements, for which I apologise, but a) I needed to make the project viable, and b) I’m not sure if people believe South American club football has been comparable to its European counterpart for 20-30 years now, partly because it’s top talents end up in Europe anyway.

And of course, some hugely influential coaches – such as Marcelo Bielsa – have won nothing that qualifies them here, but still made an impact.

And the criteria I chose means winning at least two major trophies in the last 40 years. (Anyone who did so would be included, and, if included, I’d then look back at their whole careers, predating 40 years ago. Example: Rinus Michels won the European Championships with Holland 30 years ago, so qualifies, but started managing in 1960, so his career is covered from 1960.)

My definitions of major trophies (and minor ones) can be seen below. It’s slightly different from the way people would call the League Cup a major honour and the Charity Shield a minor trophy, in that this is about the elite.

Major = Champions League, or a League Title in Top 5 League: England, Spain, Germany, Italy and Holland (up to 2008; until then, Holland had clearly been superior to nations like France and Portugal, before Holland fell off the map somewhat). Plus, World Cup and Euro Championships.

Minor = Europa League, FA Cup, League Cup – in the aforementioned leagues – and any of the minor European cups (Europe League, UEFA Cup, Cup-Winners’ Cup, etc). Does not include any Supercup games, World Club, Community Shield, etc, where it is essentially a one or two game showpiece play-off system. If you think these are important, fine. (But they’re not.)

This means some great managerial achievements lower down the ladder are admittedly overlooked, but those are all relative achievements; such as gaining promotions for clubs or taking a club on a low budget to 3rd in the table. To be on this list of 38 managers, managers have to be the elite, and that means winning two major trophies.

And if a manager achieves such relative lower-level successes they should then expect the chance to manage at a club with greater odds of winning something – even if Alex McLeish winning the League Cup wasn’t a precursor to better things; but Alex Ferguson winning the European Cup Winners’ Cup with Aberdeen later helped him to get the Man United job.

And of course, we can argue all day long about the true value of achievements, as everyone has different budgets, different players (even if they have some of the same players they will be at different ages) and different time constraints.

To me, Bayern Munich winning the Bundesliga as their own wealth grows (and as they raid their rivals), pales compared to when Dortmund won back-to-back titles with Jürgen Klopp, just before Bayern’s “close rival asset-stripping” schemes started.

How good is Zinedine Zidane when winning European titles with Real Madrid’s mega-squad? Klopp taking Liverpool to the final, as 40-1 outsiders on a fraction of the budget, is a far greater achievement, relatively speaking. But you also can’t criticise Zidane for continually reaching finals.

Interestingly, if I were to widen the criteria to “reached a major European final”, then Klopp would have three extra “points” in the last six years. But as I said, I had to draw the line somewhere (although hopefully I’ll be updating this after Kyiv and adding a major trophy to Klopp’s data.)

And so on. For now, we’ll have to agree that a major trophy (by the criteria I have set) remains a major trophy, and not add any caveats – other than the countries of inclusion, as mentioned earlier. (Adding financial components isn’t feasible here, as personally, I only have such data for the Premier League.)

From all this data I could see how long it took managers to become successful at an elite level, how long that success lasted, and how it then (usually) tailed off; including all those seasons in the wilderness trying to rebuild a reputation, or in the “retirement home” of international football.

Imperial Phase

To borrow from popular music, there is a quote from a few years ago where Neil Tennant of the Pet Shops Boys described the point in which an artist is regarded at their commercial and creative peak simultaneously as its “imperial phase”*, and this term seems fitting for football managers too.

(* From Wikipedia: “The phrase was coined … to describe the period between the release of their album Please in 1986 to the release of the single Domino Dancing in late 1988. After a sequence of number one singles it only peaked at number 7. Tennant later said: “…it entered the charts at number nine and I thought, ‘that’s that, then – it’s all over’. I knew then that our imperial phase of number one hits was over.”)

To me, the imperial phase in football is simply the greatest clustering of trophies, with priority given to major ones over minor ones. So even though Alex Ferguson’s trophies were spread out fairly evenly from 1993 to 2013, there was a slightly greater cluster from 1993 to 2001 than after that point, which included a few more fallow seasons. (Note: for the purposes of this piece I’ve just used the end of the season date, so 1992/93 is 1993, and so on.)

Obviously some managers who are still currently working may not even have reached their imperial phase, or they may still be in it, but only hindsight will confirm it. And there are of course slow-burning managers (Ottmar Hitzfeld – 300 league games as a manager in Switzerland before success in one of the major leagues); intermittent-burning managers who dip in and out of great success (Jupp Heynckes); and largely burnt-out managers (Arsene Wenger, whose career – with a decade of relative stagnation – is almost identical to Brian Clough’s reign with Nottingham Forest, as I will discuss later in the piece).

Any manager who wasn’t working at any given time is listed as having “no trophy”, even though they may have been inactive for an extended period (like Kenny Dalglish) and thus unable to win trophies.

This is because – unless voluntary – most managers will be out of work because they are no longer valued, rightly or wrongly. A lot of hitherto highly-rated managers eventually end up at clubs where there is little chance of winning things, but this in itself is in some way reflective of their diminishing powers (or perceptions thereof, by the big clubs who overlook them; they may remain great managers, but one bad spell, and, like a movie star whose last film tanked, they are avoided like the plague).

Equally, anyone working in a lower league or a division that is not England, Spain, Germany, Italy and Holland, has no data listed; so Arsene Wenger’s trophies in France don’t count in this particular study, just as Sven Goran Eriksson’s in Sweden or Portugal don’t count – but any European trophies with those clubs are included. (Again, if you want a wider study, do your own research!)

So anyway, here is the interactive data-viz created by Robert Radburn, which should be self-explanatory.

What follows is my takeaway from the data, with a slightly more LFC-centric perspective, given the nature of this site.

The second half of this article is for subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]