My motivation for writing about Liverpool has always been to give credit where it’s due, rather than where the mass media prefer to place it.

I am currently in the process of updating “Dynasty: 50 Years of Shankly’s Liverpool”. Since the book was published in late 2008, we’ve seen: Rafa Benítez’s best and worst league seasons; his subsequent replacement with Roy Hodgson, which led to two performance lows that outstrip any in the book (worst league start and worst domestic cup result since prior to 1959); and the remarkable return of Kenny Dalglish, and the upswing in results that followed. Add the club changing hands yet again, and there’s plenty for me to get my head around.

As with all of the managers covered, I will look to see what was done well, and also where mistakes were made.

However, one of the more unfathomable myths that grew up around Roy Hodgson’s tenure was the he, unlike Rafa Benítez, gave youth a chance. While it’s true that Hodgson fielded some youngsters in the Europa League, it’s also true that they barely got a sniff where it matters, in the Premier League. (And if we’re talking about blooding kids, look at the teams Benítez often fielded in the relatively unimportant League Cup, or in Champions League qualifiers and dead rubbers.)

Aside from the league, the Champions League is the only other place where games are high-profile and must-win – and where clubs do not readily field weakened teams due to prioritising (unless it’s a dead rubber). It’s not Hodgson’s fault that he never got to participate, of course, and that Benítez did. But the fact remains that the Europa League is a ‘B’ competition.

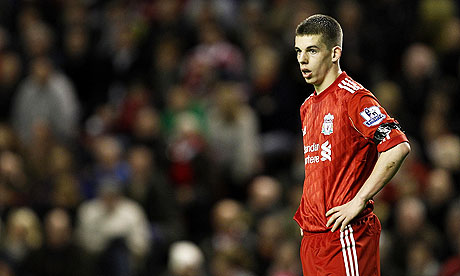

It could also be argued that Hodgson can’t be blamed if the kids he inherited weren’t good enough for league action. But a mockery was made of this by anyone who had seen the largely ignored Martin Kelly play during the previous season, or indeed, after Hodgson’s exit. (Or indeed, Kelly in the Europa League.) It’s also the case that Hodgson brought in a clutch of substandard players with an average age of 30, and in meaningful games chose them over younger players on the books.

So, how many under 21s – and by this I mean literally, and not the international football definition of U21s where, somewhat confusingly, 23-year-olds sometimes play – did Hodgson start in the Premier League? How often did he bring them on? How many debuts did he give to the starlets?

(Note: I chose under-21 as it seems a standard football cut-off point in terms of what represents a young player. Anyone 21 or over is discounted, because they are not, by definition, under 21.)

Well, in his 20 games, Hodgson started with a mighty two: Martin Kelly, at Wigan and at home to Chelsea. On top of this, seven young substitutes were introduced.

In total, Daniel Pacheco received five minutes, Nathan Eccleston nine minutes, Martin Kelly six minutes, and Rafa’s penultimate signing, Jonjo Shelvey, was given his league debut and three further substitute appearances totaling 58 minutes. Aside from Kelly’s 180 minutes, the sum total of the other under-21s was 78 minutes, still 12 minutes shy of a full appearance.

Ngog and Spearing, both over 21 by this stage, got playing time, although Spearing’s was in Europe. The only young lad who received his league debut was Shelvey.

In came Kenny Dalglish in January, and in his 18 league games, 15 starts were handed out to players under 21, spread across Martin Kelly, John Flanagan and Jack Robinson. A further eleven appearances were made by kids from the bench. In just one of these substitute appearances, Jonjo Shelvey played 78 minutes – precisely the amount of time Hodgson handed out to all of his U21 subs.

Now, of course, Dalglish, like Benítez last season, had a bigger injury crisis, therefore he had to resort to playing the kids on occasion. (Then again, Dalglish still chose them ahead of some of Hodgson’s signings.) And Dalglish still got better results with the kids than Hodgson managed with his more experienced selections (as did Benítez).

So, if Hodgson compared badly with Dalglish, how did he fare against his predecessor, Rafa Benítez, who supposedly “never gave the kids a chance”?

Well, here is a good opportunity to point out the difference between giving the kids a chance, and giving the local kids a chance. Clearly Benítez played younger overseas signings like David Ngog and Emiliano Insua more than he played local ones. But then, for the most part, Arsene Wenger does that, and he still gets a lot of credit for playing ‘the kids’ (and no-one says that Messi coming through the ranks at Barcelona doesn’t count because he’s from Argentina). There’s a difference here between buying full internationals like Lucas and Babel at the age of 20, and giving debuts to 17/18/19 year olds. I’m only interested in the latter example.

Let’s look at Benítez’s final season, seeing as that is the closest to the current day, and includes many of the players Hodgson inherited. Rafa started an U21 on 28 occasions, and introduced one as a sub 21 times. (This includes Insua and Ngog only up until each turned 21 during the campaign, in January and April respectively.)

While that pair comprise the majority of starts, league debuts were also given to Daniel Ayala, Daniel Pacheco, Martin Kelly, Stephen Darby, Jack Robinson and Nathan Eccleston. That’s six youngsters making their league bow last season, with four of them ‘local’ (from the north-west).

Indeed, Kelly was given his first start – in impressive fashion – in the big Champions League game against against Lyon, although he suffered a serious knee injury that sidelined him for several months; otherwise he would have featured more often.

Darby also started a Champions League game, but that was the dead-rubber against Fiorentina. He also gained one minute as a league sub, and Jack Robinson gained just two, although at 16 it did make him the Reds’ youngest-ever player. Eccleston got 12 minutes, Pacheco 39 minutes in four appearances, and as well as two full 90 minutes, Ayala added 54 minutes across three introductions from the bench. (Ngog made over 100 minutes of appearances as a sub that season, before he turned 21.)

This makes for 49 U21 appearances in Benítez’s final 38 league games, or 1.2 a game.

Marginally ahead, at 1.4 per game, is Dalglish.

Miles behind both, Hodgson’s nine in 20 equates to 0.45 a game, or roughly three times less frequent than Benítez.

So how the hell, apart from smoke and mirrors, has Hodgson got this reputation as ‘giving the kids a chance’? This, after all, is the man who left Mark Hughes a team with an average age of 30, and who bought players for Liverpool with that same average age. While he has his qualities (even if they weren’t really seen at, or suited to, Liverpool), working with kids is not really one of them.

Perhaps the perception also includes Jay Spearing, a player who turned 22 in November 2010. As such, he doesn’t qualify as an U21 under Hodgson or Dalglish; he is, after all, the same age as Andy Carroll. And anyway, he never started a league game under Hodgson, but did so under both Benítez and Dalglish.

Spearing made his debut in 2008, just after his 20th birthday, coming on as a sub along with 18-year-old Martin Kelly in the final group match of the Champions League at PSV Eindhoven, with just top the spot at stake having already qualified; so, almost a dead rubber, but not quite, given how top spot is seen as fairly vital.

Benítez got a lot of stick in his final two seasons for preferring Lucas over the local lad, but as much as Spearing has improved, the Brazilian won every LFC 2010/11 Player of the Year vote I’ve seen – and therefore clearly remains better.

This was not bias on Benítez’s part, just common sense in picking a Brazilian international over someone yet to even be capped by England at U21 level. Spearing has come on leaps and bounds, but of course, only since Gerrard has been injured and Alonso, Aquilani and Mascherano haven’t been around.

Average Age

Last summer I warned about Hodgson, and his preference for older players. So, was I right?

The average age of Liverpool’s starting XI under Benítez in each of his six Premier League seasons ranged between 26.0 and 26.5, with 26.3 the average in his final campaign; marginally above his overall average of 26.2.

Hodgson’s? No less than 27.73. As you can see from Benítez’s figures, the key is to lose older players and replace them with younger ones, to keep things at the same sort of level. Look at how incredibly stable the average age is. In came Hodgson, and suddenly it jumped a year and a half, even though several older players had fallen off the metaphorical cliff.

There’s nothing automatically wrong with older teams; Chelsea’s pensioners won the league last season, Inter’s infirm achieved a remarkable treble and Hodgson’s Fulham geriatrics did well in Europe. But it’s a short-term approach; particularly in English football, where fitness is such a key issue.

Overhaul

One thing I am pleased to see is that, in some quarters at least, Rafa is getting the credit for overhauling the Academy. In terms of credit where it’s due, it’s an important point to make; and one that Kenny Dalglish has frequently acknowledged.

I know from my own conversations with Rafa just how important he felt it was to produce – or find – the best young players around, and how frustrated he was with many aspects of the way the system was being run (from shoddy scouting to outdated coaching).

Benítez gave league or Champions League debuts to Zak Whitbread, Danny Guthrie, Darren Potter, Neil Mellor, Stephen Darby and various other players who never proved good enough (and still haven’t proved him wrong), and yet they were the best that he was given from Kirkby. He tried to sign Aaron Ramsey from Cardiff for a small fee several years ago, but was told that there was better at the Academy.

Following the summer of 2009, when he was finally able to assume full control in terms of overseeing the youth set-up, he brought Raheem Sterling, Jonjo Shelvey and Suso to the club: three teenagers as good as any seen at the club since the late ‘90s. And no fewer than seven Liverpool players are now in the England U19s set-up, no doubt aided by the influence of the Barcelona coaches that Rafa appointed.

And of course, Rafa brought back Kenny. Would Dalglish be in charge now but for that decision? Almost certainly not, given that it assuaged some of the doubts about him being ‘out of the game’ (in that he’d been in the game for the previous 18 months). Part of the allure was that he knew the personnel, particularly the kids.

As Rodolfo Borrell said this week: “We now have a situation where the first-team manager of the club knows all of the names of the players and staff from the U8s right up to the likes of Steven Gerrard and Luis Suarez. That is quite unique in modern day football and it means the world to all of us. I think Liverpool will benefit greatly from this in the future.”

Success from appointing a manager in this way is not without recent precedent. Frank De Boer took over at the Ajax academy in 2007, and this past winter, in a move mirroring Dalglish’s, took charge of the senior side. They too experienced a big improvement, although in their case they won 13 of the new manager’s 17 games, and snatched the title on the final day.

And of course, coach of the best team in the world (by far) Pep Guardiola spent a season in charge of Barcelona’s B team, which plays in the lower leagues. While this isn’t a youth team per se, it is still a collection of younger players. Sergio Busquets, then 18, played most of the games that season, and Pedro, then 19, was another regular. Bojan Krkić and Jeffrén also played in that team around the same time.

You could excuse Roy Hodgson for not knowing the Liverpool youngsters as well as Dalglish, and perhaps Benítez too. (Benítez will have been aware of them for longer, but only Hodgson knew how good they were in 2010/11, in order to spot any development.)

Ultimately, Hodgson picked teams he thought would win games. While I disagree with his overall approach, it was not his job to pick youngsters, particularly when most of the senior squad were fit. However, the fact remains that, in the league at least, he did not give the kids a chance.