A Doctor at Hillsborough by Neil Dunkin.

This piece was originally written for the Sunday Express in 2009, although they only published half of the article. Neil offered the full text to TTT in 2010, and I was only too glad to accept. I have bumped it to the top of TTT, following this week’s momentous and long-overdue news.

A perfect day for an FA Cup semi-final. As Dr Glyn Phillips drove with his brother Ian and two mates from Merseyside to Sheffield, they all agreed the weather could not have been better. April showers had been replaced by radiant sunshine and the Pennines looked stunning beneath the immaculate blue skies.

A beautiful day for the semi between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest.

Although he lived in Glasgow and worked as a GP in Lanarkshire, Dr Phillips, 34, had been born and bred in Huyton, Merseyside. A devoted Liverpool supporter, he had achieved the Holy Grail of every fan by obtaining a season ticket for Anfield and travelled down religiously to see the Reds. Now he was on his way to the Cup tie at Hillsborough where the four pals had tickets in the end allocated to Liverpool fans.

Once they arrived in Sheffield, they parked their car and strolled to the stadium, arriving half an hour before kick-off.

At the ground, they joined the throng of supporters and walked through a central tunnel into the Leppings Lane terrace, behind the goal.

“As soon as we got in, we knew it was an abnormally packed crowd,” says Dr Phillips, now 55. “We were carried along on our feet by the crowd. We got split up from our mates and Ian and I found ourselves near the front, on the pitch side of a steel crowd barrier.”

Dr Phillips had been in lots of packed football terraces but he soon realised the pressure of bodies in this pen was of a different magnitude.

“I’ve been on the Kop many, many times,” he recalls, “and I’ve never been in a crush like that before. It was on a completely different scale to my previous experiences. I’d been going on the Kop since the age of 12, for big, big games, derby games, Leeds and Man United games, European games. We always used to go right in the middle behind the goal and I’d enjoy the movement, the surges, the swaying of the crowd. It was part of the fun. But this was abnormal, quite sinister.

“We had to get away from there. I knew this was not a good place to be and we decided to move higher up the terrace. People couldn’t stand aside so we went down on hands and knees and crawled through legs. Higher up it was still so tight that standing up was difficult but we did it and even managed to meet up with our two friends. Then we were looking at each other with faces of incredulity. What’s going on?

“There wasn’t much you could do, though, because you were stuck, penned in by the side against railings. Imagine having your elbows down by your side and your hands up in front of your chest. You just couldn’t move your arms because you were so crammed together.

“Even then, as kick-off approached, we assumed the crush would ease and everything would be all right. I remember vaguely the match kicked off and Peter Beardsley hit the bar but you couldn’t watch the game because you were so conscious by then that it was a dangerous situation.

“You were constantly making sure your footing was right because if you went over, loads of other people were going to go over. There was a lot of shifting of position. You were getting moved to and fro, only small distances but it was impossible to resist.

“Then I became aware of people climbing the fence, trying to get out, and police paying increasing attention. To the side of us, on the right, down towards the pitch, alongside the fence running perpendicularly up the terrace, people were becoming very agitated. That was an area with loads of space to move around, in contrast to where we were.

“Lads were yelling: ‘Get back, get back. There’s fans crushed at the front’, and they were becoming very upset because people didn’t realise what was going on. And you see very limp bodies getting hauled out and you think: ‘Oh shit, something really bad is happening.’ Then someone ran on the pitch, yelling at Liverpool’s goalkeeper Bruce Grobbelaar to stop the game.

“Minutes later, we’d climbed over the railing into the next pen which was relatively empty. I was looking down at the pitch and could see the state of some people and I thought: ‘God, they’re dead. I’m going to have to go and try to help.’

“So I made my way down to the front where there was a gate in the fence, on top of a low wall. I shouted to a policeman: ‘I’m a doctor. Let me on the pitch.’ I put my hand out to him and he pulled me up the wall, but we didn’t realise there was a cross bar in the gateway. As I leapt up, I cracked my head on this bar.

“It nearly knocked me out. I was seeing stars. A hell of a blow, causing a scalp laceration. Blood was streaming down my face. I shook the blow off and walked on the pitch, which was full of people milling around. Chaos, chaos.

“I’m thinking what to do and literally the first body I came to was this young lad, a teenager. He wasn’t breathing, no pulse, ashen, grey, clinically a cardiac arrest, and I knelt beside him and started doing CPR (cardio-pulmonary resuscitation). There was a guy next to me — he said he was a male nurse — so while I did mouth-to-mouth, he did chest compressions.

“As we worked away, I was aware of a lot of people suffering in the pens. I thought if this lad is this bad and he’s on the pitch, then the ones still in the pens have no chance. I thought I’ve got to give him a decent chance, so I stayed with him.

“I asked some policemen for oxygen and an oxygen cylinder arrived. This is a big bone of contention in the statement I made afterwards and the subsequent inquiry into the disaster. To my best knowledge, the oxygen cylinder was empty. The gauge was reading empty. But this was part of the inquiry when at least one QC wanted to discredit my evidence. It was eventually deemed that on the balance of probabilities I was wrong because I admitted I was angry and I’d had a heavy blow to the head.

“Anyway we carried on working on the boy as he didn’t have a pulse. We must’ve been there five, 10 minutes and I was on the point of giving up when I felt a femoral pulse. He had developed a healthy, bounding pulse. Against the odds, his heart had spontaneously started again. He was completely unconscious but he started making some efforts at breathing.

“So we got a stretcher and carried him into an ambulance behind the goal. There were two others on the floor inside but they were dead. We put the lad on his side in the recovery position and I decided there wasn’t a lot more I could do. I don’t know if that was the correct decision, if I should’ve stayed with him, but his heart was going, he was breathing.

“I remember saying to the ambulanceman: ‘Keep an eye on him. If there are any problems, give me a shout.’ The daftest thing to say, with all this chaos going on, but you didn’t think that at the time.

“As we had carried the lad to the ambulance, I’d been aware of eight to 10 bodies in the goal area. Inside you’re struck with this desire to be professional and do what you can but at the same time incredulous this has happened in the space of half an hour, at a semi-final, on a sunny day. There are all these young lads lying dead.

“I went back looking for others to help. I tried CPR on a few more people but they were gone. It’s horrible trying to resuscitate people who are effectively dead, the taste of vomit and all that kind of thing, but I have to say there was no hint of alcohol on any of the young people I attempted CPR on.

“And getting into the game we did not observe any misbehaviour. A bit of boisterousness you get with any football crowd but no bad behaviour, nobody inebriated or out of control, in contrast to the allegations made later in some newspapers.

“By now I was basically on the pitch scouting for somebody to help. It must have been after 3.30 and by then people were walking and talking or sitting and talking or they were dead. Nothing much in between.

“The last person I tried to resuscitate was in his 20s. I think his brother was trying to revive him and I remember this girl wearing a Celtic top saying: ‘Leave him, he’s gone, he’s gone.’ I had a go but he was dead.

“Now I was down the far end of the pitch, where this mass of Forest fans were just standing, watching in stunned silence. I saw two photographers by the goal and what was growing in my mind, among all this clinical stuff and the incredulity, was that I was very conscious of what the media did to Liverpool after Heysel, where the majority of 10,000 fans did nothing wrong and as a result of the incompetence of stadium officials, UEFA and Belgian police, 26 nutters were able to cause mayhem. Juventus had their share of morons, too, but that was conveniently forgotten.

“I thought they will try to blame this on the fans. I can’t let that happen. So I went up to the photographers and said something along the lines of ‘I hope you’re going to stuff this ground when you write it up.’ I made a few remarks about the lack of facilities and they asked what I did. I said I was a GP and I’ve just been trying to resuscitate dead lads. As soon as they heard I was a GP, not just an overgrown scally fan, they thought here’s someone worth quoting, so the notepads came out and photographs were taken.

“Then I thought I’ve got to speak to someone from Liverpool Football Club, to make sure they don’t let the fans get the blame. I boldly went to the players’ tunnel. There were police all around. I said I was a GP and had to speak to someone from LFC. They didn’t even attempt to stop me. I think they were all stunned. Anyone who sounded as though he had any degree of intellect they let through.

“As I made my way up the tunnel, Jimmy Hill was there so I told him what had happened. Alan Green, the BBC football commentator, was standing there listening, and he asked if I minded speaking on the radio. Next thing he was introducing me live, I was saying what I’d witnessed and it came out, almost in one breath.”

Dr Phillips told the radio audience: “There’s no doubt this crowd was too big for this ground. Liverpool just filled the end they were given. The police allowed the fans to fill the middle terracing section to the point they were crammed in like sardines. And yet the two outside portions of the terracing were left virtually empty and I stood and watched police allowing this to happen.

“It got to a point where they lost control completely. Lads were getting crushed against the fence right down near the pitch and there were so many people in that part of the ground that nobody could even move to get out. I climbed sideways into an emptier section and then made my way on to the pitch to try and help.

“Now unfortunately there are guys who have died down there on that pitch. I’ve seen about eight to ten, I don’t know how many there are.

“There was one chap I went to, he was clinically dead. He had no heartbeat. Myself and another guy – I think a nurse – we resuscitated him for about 10 minutes. We were just about to give up when we got his heart beating but I don’t know what the state of his cerebral functions is going to be like.

“We asked for a defibrillator. I’ve been informed there isn’t a defibrillator in the whole ground, which I find appalling for a major event like this. We were given an oxygen tank to help with our resuscitation and it was empty. I think this is an absolute disgrace.”

With that, Dr Phillips ended his comments and walked back on the pitch.

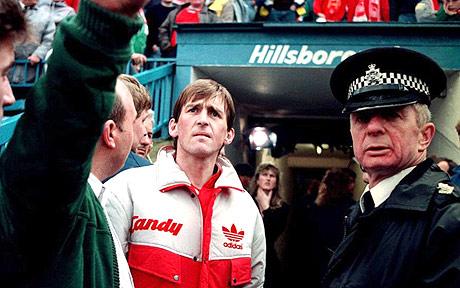

“As I was about to leave the changing room area, by chance Kenny Dalglish was there, looking ashen-faced because, as I learned later, his son had been in the crowd. I introduced myself and told him very, very quickly what I’d just witnessed and I said you mustn’t let them pin this on the fans. This was not fan trouble. The crowd conditions here were a disgrace.

“He said something like we didn’t want to play here but had little say in it.

“I then went up the terrace and rejoined my brother and two friends at the top where they’d stayed while I was on the pitch. They were stunned, disbelieving what had happened.

“I’d done what I could. I’d tried to help revive people. I’d also made sure people who needed to know what really happened had somebody with some credibility telling them. Bizarrely I’d got a chance to speak out on the radio, which had one personal advantage.

“My wife was at home in Glasgow, very upset and anxiously watching events on telly, knowing we were in that terrace. Thankfully one or two friends heard me on the radio and phoned her within minutes to say I was OK.”

The four mates left Leppings Lane and returned to their car for the journey home to Merseyside.

“I was in the back, reflecting on events and listening to the radio,” says Dr Phillips. “They replayed my little outburst two or three times, leaving me with a total sense of disbelief. What my friends couldn’t quite get was how dispassionate and comprehensible I was, which surprised me because when I was speaking I thought I was shaking with anger. More importantly, we were all horrified and upset by the steadily increasing death toll.

“We made our way back to Rainhill where my folks lived and I made an emotional call to my wife. By this time I was feeling quite numbed by everything and very conscious of the media interest. Papers wanted to get hold of me. They’d heard about this GP from East Kilbride, so the press officer for Lanarkshire Health Board had to come in off holiday and field calls.

“Next day, Sunday, I drove to Glasgow and realised how preoccupied I was because I made it in three hours, about an hour quicker than normal. I just clogged it. I was back before I realised it.

“I got into work on Monday morning and knew I couldn’t do the job. It felt as though I shouldn’t be there. I needed to be in Liverpool. So I told my partners in the surgery: ‘I’m going to have to go off for the rest of this week.’

“That evening I returned to Liverpool and we went to Anfield where we tied some flowers with our scarves to a barrier. That was emotional but I had such mixed feelings. It had been pointless and preventable. Innocent lives had been lost and in the midst of all this you’ve got despicable elements in the media attacking vulnerable people, bereaved parents, brothers and sisters having to read or hear rubbish about their lost loved ones.

“I was increasingly angry with the media and notably the most astute observation of that whole week came when Neil Kinnock, the Labour leader, was being interviewed on the pitch at Anfield. He was surrounded by scallies and whatever and this teenage voice piped up about the police: ‘The bizzies fucked up.’

“I thought that sums it up. Why isn’t he being interviewed? Absolutely dead right, and subsequently it was established he got it right. The stewarding and policing were incompetent.

“While staying on Merseyside with my family, I gave interviews to ITN, Granada, an American TV company at Anfield. Then I just had this sense I wasn’t going to resolve this. By now there was a video running in my head about the events of the day, what I did, what I should’ve done. I thought I’ve got to go to Sheffield to find that boy on the pitch, find out what happened to him.

“The following Friday I drove over on my own and went to the ground. People were there to offer support and I was met by a woman social worker, Dee, who was great. She allowed me to walk all the way around the pitch and I told her my story, what had happened, what I’d witnessed. She was very, very supportive. That was therapeutic.”

After qualifying as a doctor at Leeds University, Dr Phillips became a medical officer in Royal Navy nuclear submarines and he says: “In military psychiatry, there’s a well-known phenomenon, a need to resolve traumatic events. It’s called revisiting the battlefield. Being back there on a calm, sunny day when the chaos has gone, that helps put the matter into perspective.

“Going back certainly helped me. When you’ve been part of a traumatic event with loss of life which is very upsetting, returning to the scene and seeing it’s no longer going on definitely helps people get through these things.

“From the ground, I went to the two main Sheffield hospitals to find the boy. I thought he’d be in intensive care if he’d survived. I was discreetly allowed to look at some people who were being cared for and I didn’t recognise him. I now know why, because he was totally swollen up. But he was there in intensive care.

“I came to the conclusion he’d died and I felt pretty low about that. I beat myself up, thinking I should’ve stayed with him. Having got him going again, I should’ve made sure he was OK.”

After the tragedy, West Midlands Police launched the biggest inquiry in British legal history to ascertain what happened at Hillsborough and in March 1990 Dr Phillips was asked to watch video footage. He went to Knowsley Hall, Lord Derby’s home just outside Liverpool, where investigators had temporary offices for the examination of tapes which they hoped would establish where people had been on the fateful day.

“I was watching this video with a police officer,” says Dr Phillips, “and by chance I fleetingly saw myself on the pitch, on my knees over this body. I said that’s the first lad I tried to help. The constable said: ‘We’ve got his name and I don’t think he died. I’ll look through the records and get in touch with you.’

“A week afterwards, the police officer phoned: ‘We know who it is, an 18-year-old lad, Gary Currie. He survived and his family is very keen to meet you.’

“So we arranged to go down to Huyton and see Gary. Coincidentally he lived about half a mile from the primary school I’d attended as a young boy.

“Meeting him was a moving experience. Sadly he hadn’t survived unscathed. His heart had stopped and he suffered some anoxic brain damage, so he’s not as he was. He’s disabled, on permanent medication, and can’t work. But he can walk and talk and has still got his sense of humour. And he is still a massive Reds fan.

“His family were just delighted he lived. Two years after the disaster we were invited to his 21st and have kept in touch occasionally ever since. In fact, every Christmas he and his mother Alice send me a Liverpool FC calendar and a kind gift for my son.”

Dr Phillips was also called to give evidence to Lord Justice Taylor’s inquiry into the disaster but oddly he wasn’t invited to the subsequent inquest.

He says: “At the Taylor inquiry, a panel of barristers represented various bodies … South Yorkshire Police, Sheffield Wednesday, South Yorkshire Ambulance, St John’s Ambulance, the stadium engineers. There was a row of them. On his high desk was Lord Taylor and below him the Treasury Solicitors, QCs representing the Government.

“I naively thought I was providing a public service but only after my questioning started did I realise this was a game, not a very funny game. At least one QC wanted to discredit me, basically a dirty tricks technique. I had been widely quoted as being critical because there wasn’t a defibrillator and the oxygen cylinder was empty, so they wanted to make me look like an idiot.

“I was handed this photocopy of a series of heart readings, ECGs. They were very poor quality and it was time for trick questions. A QC asked: ‘What do you think this first tracing is?’ I looked at it and it was just a squiggly line.

“The subject under discussion was a condition called ventricular fibrillation where the heart has effectively stopped beating but is electrically quivering. I said it could be VF and he jumped right down my neck, smugly saying: ‘Actually, Dr Phillips, this is a recording where the leads of the machine have been loose.’

“I thought what a smart arse. I instantly went from naivety to the full realisation this was to make me look stupid. I could feel my hackles rise. If it hadn’t been in that setting, I’d have given him a piece of my mind. We’re trying to find out what happened to young people who died unnecessarily and you’re trying to make me look like an idiot, having volunteered to give evidence. I thought, all right, that’s what we’re playing, are we?

“Then he brought my attention to another tracing and asked: ‘How would you treat that?’ As disdainfully as I could, I said: ‘Well I wouldn’t treat it because it’s a piece of paper. What I want to know is some detail about the patient it represents. Is he conscious? Is he breathing? Has he got a palpable major pulse?’

“And the QC just looked at Lord Justice Taylor and I looked at the two Treasury Solicitors. They both had broad smiles on their faces because I was playing the game how lawyers play it. And this first QC said: ‘Oh, we’ve already had expert witnesses about defibrillation. I think I’ll leave it at that.’

“That was distasteful. I really felt quite low at that point. I’m offering some helpful observations and you want me to look like an idiot and you weren’t even there. I felt disgusted. Anyway my evidence was over pretty quickly and I just left feeling totally deflated. We’d had it from the media and now we were getting it from the legal profession. In all fairness, though, I believe that Lord Taylor was more than a match for such tactics and that in general he did a great job in deciding what was the root cause of the disaster.”

Now, every year on the anniversary of Hillsborough, Dr Phillips thinks back to what happened and still feels a sense of utter disbelief.

“For decades, fans had been treated appallingly by football clubs, treated with contempt,” he says. “At away games that contempt was shared by local police forces. If you went on the terraces, you were basically unworthy. We put up with it because we loved the game. We didn’t realise the danger we were in.

“When you were in a crush, there was always an assumption it would ease, the wave of pressure would go. The difference at Hillsborough was it didn’t ease. It just got worse. This had happened before when Tottenham played there. People had to be put on the pitch because the crush was dreadful.

“What made it deadly this time is they didn’t police or steward the influx of fans and this crazy notion they would find their own level was literally a fatal mistake.

“I still feel a terrible sense of waste. These young lives were lost pointlessly through going to watch a football game and the families feel their case hasn’t been properly listened to, especially at the inquest.

“There’s another abiding memory, my disgust at the legal profession. An hour later they’ll all be in the bar, having a drink and having a laugh about that witness who’s got one over on the opposition. It’s a game. But this was literally talking about life and death.

“My brother and I had been on the pitch side of the barrier which subsequently broke. It could well be that our instinctive decision to crawl up the terrace saved our lives because we got away from where half an hour later 80 or more died.

“Ian is 13 years younger than me and I’d introduced him to being a Kopite from an early age. I had nightmares for months about what so nearly might have happened to him.

“We were the lucky ones though.”

Neil Dunkin is the author of Anfield Of Dreams: A Kopite’s Odyssey From The Second Division To Sublime Istanbul