“Facts” can be slippery, but some things are clearly quantifiable.

Countable penalties and VAR calls can indeed be called facts. The number of penalties a team gets is … the number of penalties it gets. It’s harder to count the decisions not given, of course (such as Diogo Jota being poleaxed at Spurs).

But we can see an absence of expected instances in the data, just as there was an absence of men in the Census data after WWI, and an absence of babies being born thereafter, with not as many men to father them.

I had prepared something on the penalty-box-touches-to-penalties issue a couple of weeks ago – using data going back to 2017, which is when Statsbomb’s FBRef.com starts listing the data. I never quite finished the piece, along with dozens of other half-finished ideas.

Indeed, at the end of the Football Writers’ Podcast this week I had to listen to how VAR clearly favours the Big Six, due to Liverpool’s penalty at Crystal Palace (which to me, was a clear penalty, based on the keeper being the one out of control and sliding; Law 12 stating that the ball just has to be in play, and not for anyone to have it under control). As ever, a good podcast was ruined by a complete lack of facts, and lots of triumphant emotion.

Then TTT stalwart Andrew Beasley wrote a piece for the Liverpool Echo on the issue, and I wanted to take his fact-based piece further. So I thought I’d finish my piece:

Andrew wrote:

This was only the second Premier League penalty awarded to the Reds once the ref had seen the footage in the two-and-a-half years that the VAR system has been in place, and the first for a foul.

No team who has been in the division through the entirety of the VAR era has been awarded fewer penalties via video review.

In total, 26 percent of penalties in the top flight have been awarded following input from the VAR where for Liverpool that figure stands at just 13 percent.

Indeed, for further context on the Big Six balance, football/stats writer Grace Robertson tweeted:

“The big six have got about 40% of the touches in the opposition penalty area this season and about 40% of the penalties. Spooky.”

“Let’s be fair, it’s 39% of the touches and 40% of the penalties. What an advantage.”

The big six have got about 40% of the touches in the opposition penalty area this season and about 40% of the penalties. Spooky.

— Grace Robertson 🏳️⚧️ (@GraceOnFootball) January 24, 2022

Correlation

What’s weirder is that if you go back to 2017, virtually the exact same pattern emerges: 39.5% of all opposition penalty-box touches are taken by the Big Six, and they won 38.1% of the penalties; so again, a clear correlation between penalty-box touches and penalties won, with the Big Six in the bigger dataset a fraction under the expected rate.

But for all this correlation, there’s a big discrepancy between clubs in the data. This is why I’m often moaning about this stuff, as I track the data, and track the inequalities. Correlation doesn’t mean causation, but it seems to track to within 1% of expected outcomes across the league … but not across the Big Six.

Unless, of course, people think that Liverpool’s strikers are not fast, skilful, lethal goal-threats spearheading an über-exciting attacking team, who therefore don’t merit penalties when they enter the opposition box?

The Big Six Aren’t Treated Equally

Ex-referee Peter Walton, writing in The Times a few weeks ago, when the Big Six clubs all seemed to get a penalty on the same weekend:

“In reality, the ‘big’ teams are more likely to attack, and the longer you spend in an opponent’s penalty area, the more chance you have of winning a penalty.”

Again, that would be backed up by the overall trend, since 2017. Overall, it’s a spot-on correlation.

However, the specific teams that get the penalties – and the number of touches they have in the opposition area – is wildly out of keeping with expectations.

Some clubs are massively helped or “over-rewarded” by decisions; other clubs massively hindered, or “under-rewarded”. It all averages out to a logical conclusion, but only due to massive inequities within the dataset.

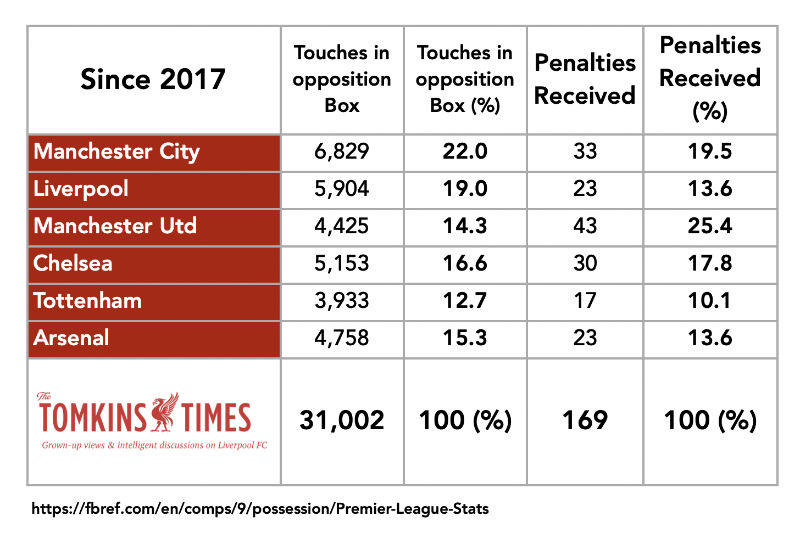

Looking only at the Big Six, Man City have 22% of the opposition penalty-box touches those clubs have racked up, ahead of Liverpool on 19%, Chelsea on 16.6%, Arsenal on 15.3%, Man United with 14.3%, and Spurs on 12.7%.

But:

• Man City are slightly under-rewarded on penalties, getting just 19.5%, despite the all-teams correlation suggestion they should get 22% of the penalties.

• Arsenal and Spurs are also slightly under-rewarded.

• Chelsea are slightly over-rewarded.

• Manchester United are massively over-rewarded.

• Liverpool are massively under-rewarded.

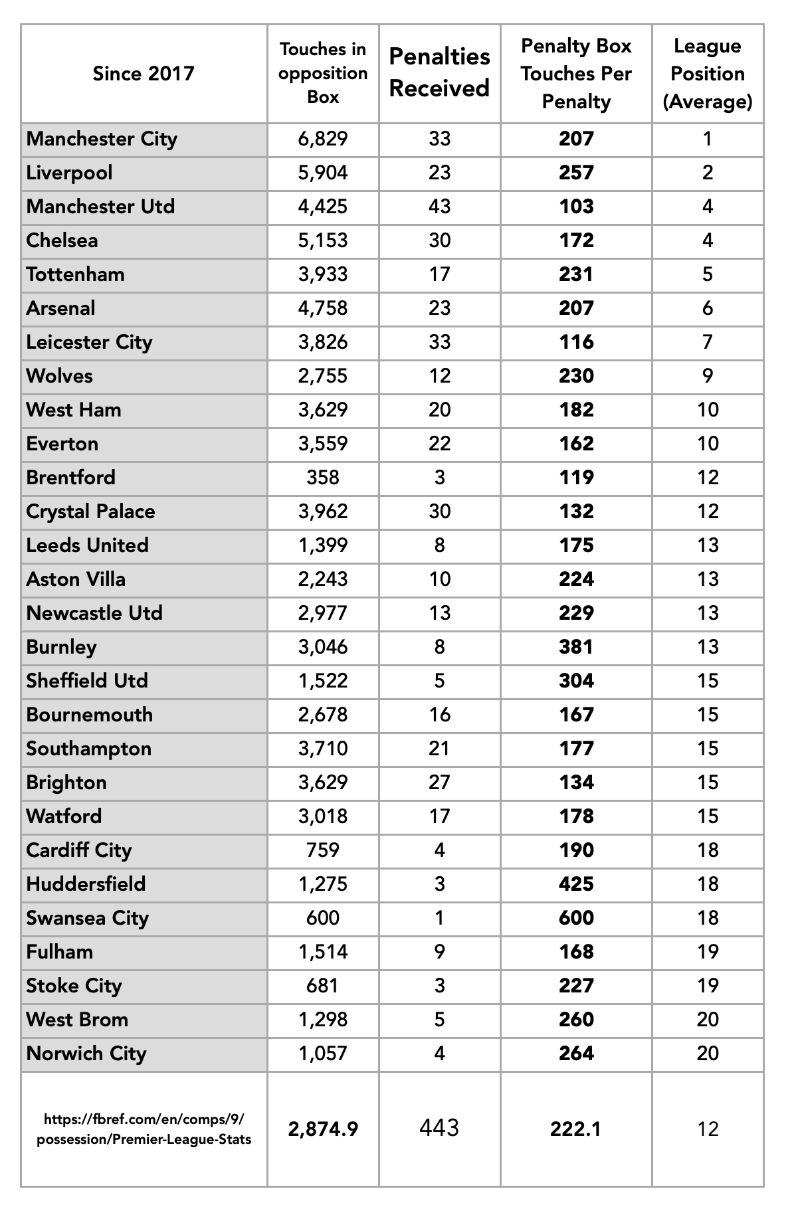

Manchester United get a penalty for every 103 penalty-box touches; Liverpool get one for every 257. All the other Big Six clubs sit in between. While City are not treated favourably by refs, Liverpool are treated even less favourably. Indeed, out of the Big Six, United get more than a quarter of the penalties.

Again, whatever you think of my pro-Liverpool or anti-Man United bias, the data is the data.

The data is the data is the data.

The Data

See the data for yourselves:

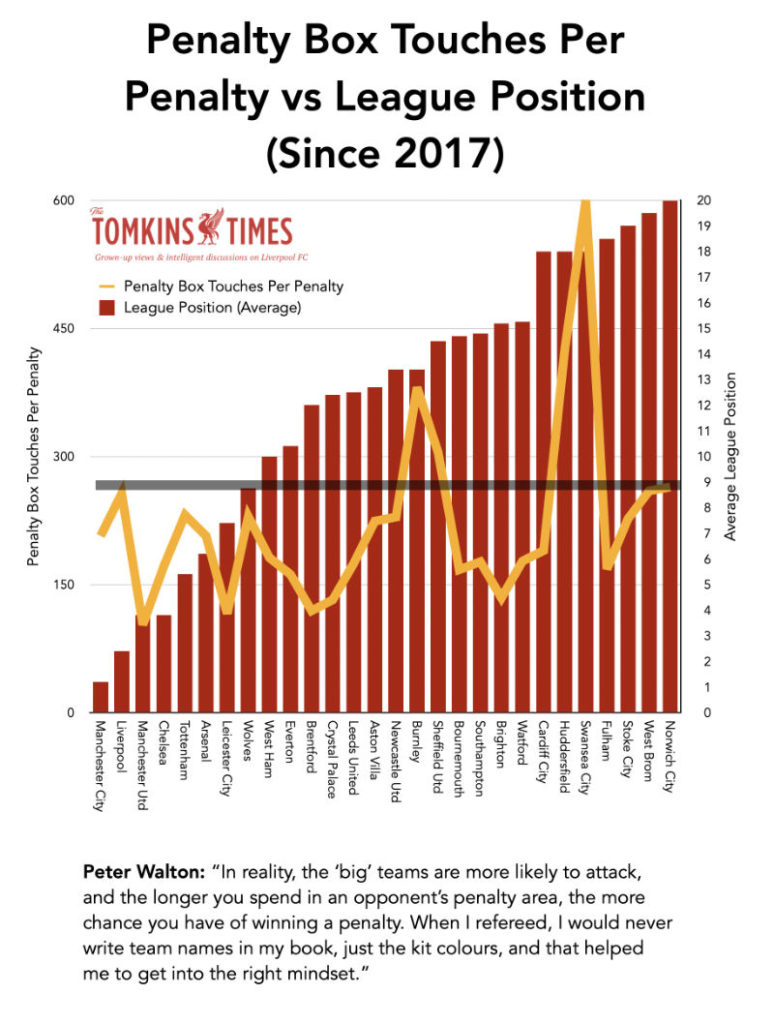

The chart below, while a little busy, shows that only a few clubs (where the orange line goes above the grey horizontal line) need a high number of penalty-box touches to get penalties, with the red bars representing the average league position since 2017.

You have to go all the way down the table to Burnley (average league position 13th to find a club who gets fewer penalties per penalty-box touch.

Here’s the full list of Premier League teams, penalty-box touches and penalties, dating back to 2017 (correct as to a couple of weeks ago).

Go back even further (to when Jürgen Klopp arrived), and Liverpool rank below Crystal Palace, Everton, Brighton and Leicester City for penalties received, as well as most Big Six clubs. (Bournemouth averaged two penalties more than Liverpool per season when in the top flight.)

You can accuse me of all the bias in the world, but what I do is based on data, not impressions, and not the confirmation of a theory by one highly-publicised incident (which gets magnified in people’s minds to being far more widespread; as with high-profile news stories that make such events seem more prevalent).

Equally, I have shown that over the past 5-6 years, English players receive a statistically significant number of decisions (about 10-20% more than expected) in their favour at both ends of the pitch, when it comes to penalties. You can talk about my biases, but the data shows officiating biases. (There appears to be no bias based on race, but a bias based on foreigness.) If you’re the England captain, you probably get treated even more kindly.

Again, I’ve showed that the big issue is often Anfield, where Liverpool get scandalously few penalties. The bend-over-backwards bias is one I termed for anyone who has to ignore reality to not be accused of bias.

Bias Goes Backwards

Take the situation Jamie Carragher finds himself in at Sky. Going back a few months, Mo Salah scored the 2nd-best goal of the season, a week after he scored the best. This appeared in The Athletic:

He [Carragher] offers the example of Salah’s goal against Watford recently: it didn’t receive the full “giant iPad” treatment on Sky Sports’ Monday Night Football, which wasn’t a conscious decision, but the idea of lavishing too much praise on a club with which one of the show’s main pundits is associated was a consideration when leaving it out. [My emphasis.]

So, er … it wasn’t a conscious decision to not feature the goal, but it was a consideration – and considerations are conscious by their very nature.

It shows the nonsense of bias, and trying to hide it, lest people go mad at you. It’s not a “conscious” decision … when it’s clearly a “conscious” decision.

It was a goal that, more than 99% of the others you’ll see analysed on Sky, deserved the “giant iPad” treatment. But the pressure on Carragher and Sky was to turn a blind eye, a bit like a referee who sees Mo Salah scythed down in front of the Kop, and who knows what online, radio, newspaper and television abuse is coming his way if he points to the spot.

Carragher also said:

“You’re always going to be accused of bias but it doesn’t affect me one bit. I think you’ve got to be careful, so you can’t be accused of that all the time. Sometimes you think it’s best to leave something, because you might get accused (of bias).”

Again, if you leave something out because you’ll get accused of bias, then you can’t say “it doesn’t affect me one bit”. You’ve just admitted that it changes what you include in the show. Clearly Carragher, who loves the club, wanted to include analysis of the goal. Who wouldn’t?

This is how bias works in the modern world: everyone has to signal that they’re not biased, sometimes with illogical behaviour or untruthful statements (to keep their job/friendships/followers/in-group).

I fully understand the position Carragher is in (especially with the lunatics on Twitter who constantly barrage you, which makes the outrage feel even greater than it actually is), but someone like Micah Richards on the BBC has no such qualms, as a blatant Man City cheerleader.

(Phil Thompson also used to be totally red-eyed on Sky, and lots of ex-players don’t hide their biases, but they tend to not want to be taken seriously as pundits, whereas you can tell that Carragher and Gary Neville take what they do seriously, banter aside. I find Carragher and Neville offer better analysis on Monday Night Football, when they’ve had time to analyse some data that they may have requested or been handed by researchers, and they’re not reacting emotionally, or trying to hide their true emotions – even if the show is clearly being edited to reduce accusations of bias.)

I get that, in “neutral” media, people often have to try and suppress their bias, but this can also suppress the truth (i.e. Mo Salah scored an otherworldly goal at Watford, and the entire show should have been centred around it, instead of ignoring it. While obviously not as serious, this is like a right-wing or left-wing media outlet ignoring or downplaying a terrorist attack because it was from “their” side, whilst the other side uses it as propaganda. If it’s your side who is being violent, the person will often be deemed “mentally ill” or a “lone wolf”, and downplayed.)

I got accused of bias on Twitter for saying that the Palace keeper was out of control and Jota had a right to take the hit; but I also said that Alisson was nowhere near the ball last season when Ashley Barnes essentially kicked Alisson to win the penalty, and that it was still a penalty. (Given that Alisson slid, missed the ball, and Barnes was free to take the hit. It’s not Barnes’ job to leapfrog Alisson so as to not get a penalty, and to leave his foot dangling meant there was contact, but Alisson was the one out out control.) I also thought that Roberto Firmino’s role in the 2nd goal should be deemed offside, as I think – not through bias but through my views on the game – that any player who tries to play the ball (or dummies the ball) is interfering in a direct way, as opposed to the less direct, but still interfering, runs off the ball. But those are rarely given.

I try not to adjust my views on football to fit what happens with Liverpool FC, but the accusations were there. (Of course, we all have biases, and we all fail to conceal them at times – but we should try to acknowledge them, but also, try not to go too far the other way.)

This is the problem with biases: the biases themselves, and the overcorrection to actual or perceived biases, where the narrative is skewed too far in the other direction.

To get back to penalties, a referee is reacting to the perception that Liverpool get too many penalties; and too many penalties at Anfield; and too many penalties at the Kop end.

All may have been true in the past (which is how biases can form), but they are the opposite of true between 2015-2022.

A referee is worried about being accused of bias. As it is, Liverpool get a relatively rare penalty at Crystal Palace (after a keeper slid into a Liverpool player who chose not to get out of the way), and as ever, the whole world seems to explode over it.

Our analysis of the referees who give far fewer penalties to Liverpool than expected (from 2015 onwards) showed that older referees, who grew up with the myth of the swaying Kop influencing referees, were less likely to give the Reds decisions than younger referees.

It showed that the nearer to Liverpool a referee was born, the less likely he was to give the Reds a penalty. (Or rather, those from the north-west were the harshest on Liverpool, with the acceptation of Anthony Taylor; and those born between Manchester and Liverpool were harsher than those born in Manchester.) Referees born outside the north-west were generally fairer, and yet Covid-19 meant more local referees took charge of games (to reduce travelling), and last season, Liverpool were shafted even more than usual.

Whether or not it should have been a penalty at the weekend, the outrage about “how many” penalties Liverpool get is just another way of making sure that the Reds get even fewer penalties.

A good place to start, as ever, would be to look at the data.