By TTT Subscriber Anthony Stanley.

Anthony Stanley is the author of “A Banquet Without Wine: A Quarter-Century of Liverpool FC in the Premier League Era”, which you can order here.

Hey all. It’s been a while.

Like many, I’ve suffered with my mental health. And even before lockdown and the pandemic becoming a grim reality, I’d been taking a break from any writing. But as often happens in life, there was a marvelously serendipitous moment during the week when Facebook reminded me that it had been three years since The Tomkins Times had, still rather surreally, published my book, A Banquet Without Wine. Two days before three decades of yearning is to be finally ended, well, I just thought I had to write something for the site. In March, Chris had very kindly contacted me to make sure all was okay and I’d explained my guilty little ache whenever I thought of football. Well, now of all times – and possibly because of what’s going on in the world, rather than despite it – it’s time for me to put the guilt to bed. On the day of another Jordan shuffle, the one I’ve wanted more than anything, the one I had convinced myself would never happen without the input of a petro-state, the one I had wrestled with over the past few months and asked myself constantly was it wrong to wish for footballing immortality when the mortality of hundreds of thousands of people was being put in stark contrast. On this day, when the titular wine from my book will be flowing, both figuratively and literally, it feels right to scribble a few words. So please allow me the indulgence of a football fan’s queer solipsism. I finally feel able to articulate my feelings on this gorgeous denouement to what has been a campaign of Dickensian proportions; the very best of times and the very worst of times.

When Sister Sledge was entreating Frankie to please remember them, when George Michael crooned about careless whispers, there was a boy of eight who was a natural contrarian. The boy still remembers his father – a Manchester United fan – and the excitement that his father held for the forthcoming (live!!) FA Cup semi-final between his dad’s beloved Red Devils and the enemy – Liverpool. That match was as alien and removed from our current sensibilities as the moon; the pitch a heaving, churning and blasted landscape from a farmyard, the ball gathering mud and seeming to bloat, to defy gravity, the players, Liverpool’s bedecked in a gloriously 80s style yellow, a far cry from the hyper-athletes they would evolve into with the fullness of time. The boy fell in love with the sport but, to the understandable consternation of his father, not the team from Manchester. Because something else happened a few short weeks later – the first of the twin H-bombs that a football club would take decades to recover from. As the boy struggled to come to terms with the concept of mortality (hooliganism was nothing new, death was something new) in the summer of 1985, there was a kind of awakening. Heysel – the scene of tragedy – became the perfect juxtaposition for what would become the tapestry for the next few years and would seal a love affair and an obsession; the dance of triumph and despair, of hope and of disaster, would become the soundtrack to his footballing supporting life.

The following seasons – the thrillingly close battle with Everton that culminated in a Double, Rush’s last season as his mythic power of scoring and never being defeated deserted him before he headed to Turin, the epoch-defining (or so it seemed to a ten year old) brilliance of the Barnes, Beardsley, Aldridge attacking trident. These were all the backdrop to feverishly consuming everything on the Reds. VHS cassettes, books, Shoot, Match. All devoured with abandon, with need and desire. The boy was eleven when he walked into a newsagent’s to pick up his copy of Shoot, only to see Ian Rush in the blue of Everton, waxing lyrical about his apparent idol, Bob Latchford. The fact that the date was April 1st (and how illustrative is that of such a simpler time) was lost on that youth as he ran from the shops to his dad for solace, a feeling of dread that things could change, that Liverpool could falter, beating a prophetic pulse in his chest.

And then it seemed that life’s education – not just football – culminated in more tragedy, in the inescapable loss of Hillsborough. It was, in the eldritch memories of a forty-two year old looking back, eerily similar to the last few months of this year; football was on hold, life and death was more far more important than any sport, how could one have a passion for a game when people were losing their battle for life? Of course, an eleven year old is ultimately selfish, cannot fully grasp the enormity and finality of mortality, and can only see the impact on their own life. Even as the stark horror became apparent, even as advertising hoardings were taken down to be used as makeshift stretchers, the boy was still remembering Peter Beardsley hitting the crossbar with a looping, acrobatic volley in the opening moments of that semi-final. It took the weeks of funerals, of seeing heroes with their faces etched in sorrow, of a city coming to a standstill as the Kop was awash with flowers, for the boy to realise just what had happened. And here, I suppose, is the perfect time for an interlude, as the man grapples with similar feelings.

The spring of 2020, four months after Alexander Arnold’s right foot made it 4-0 and finally, finally, I’d allowed myself to say this is our year and actually mean it. Now, the world seemed to be burning in eschatological and apocalyptic fire as the virus gripped our imaginations as well as potentially our body’s cells. The oft-quoted Shankly-esque idiom of football being more important than life and death, well, I was struggling with that. I wavered between a quiet rage inside my soul, a lashing out at the capricious universe for denying us our league and a stoic acceptance that I may have to give up on football – and, in particular my obsession for Liverpool. And then, listening to the Anfield Wrap one day (this in itself was rare in April, I could rarely bring myself to listen to football podcasts), I had an epiphany. I think it was Paul Cope that articulated something I had been struggling to articulate, something that had been bubbling away inside my subconsciousness, buried but, like Ozymandias, barely so and a legacy of the past. Because hadn’t I written – on this site – before on so many occasions that football was just a part of life that we humans had invented to make our time on earth more bearable. What’s the point of life without the arts, without The Sopranos, without Ian McEwan and Irvine Welsh, without Radiohead or Elbow or Sigur Ros, without The Dark Knight or Trainspotting, without everything we have invented to spend our time on this planet.

Without football.

The whole worry of the pandemic was (and is) not life or death; it’s life and dying early. We all know we are going to die but we hope that our loved ones and ourselves will get our three-score and ten. Humans are truly ingenious at inventing things to pass the time, to stop us thinking about grim reapers and to fend off existential angst. We invented money, religion, war, in a real way, time itself, to help define our lives. So it was that as tentative news of project restart began circulating, I felt like I could embrace my passion again without guilt. There would be worry, of course there would, for my loved ones and for the impact of my dying (I’m asthmatic and an arch-worrier, not a great combination right now) on them. But I could allow myself to thrill again at the prospect of my beloved Liverpool adding meaning to my life.

Back to 1989, when Tim Burton reinvented Batman and Michael J Fox, decades before his own existential crisis, sealed his iconic superstardom with Back to the Future Part 2. Football came back – it will always come back – and the Reds, those beautiful, gorgeous heroes, reeled in Arsenal and defeated Everton at Wembley, a supercharged occasion that had that eleven year old boy in tears, struggling to make his peace with life and death, with triumph and tragedy.

With football, and its place on this bewildering and kaleidoscopic landscape we call existence.

Another Double beckoned, surely. The boy suffered an asthmatic attack soon after the FA Cup victory. He listened from his hospital bed as, days after Ronnie Whelan had lifted the latest in a long line of silverware, Liverpool battered West Ham United 5-1. Arsenal now had to come to Anfield and win 2-0 to take the title from the Reds.

We all know the fucking score here.

Again, that dance. That dance between life and death, between football and its place in things. The boy in his hospital bed on a drip as his dad arranged for a TV to be brought into the ward. The boy knew he was lucky, even then, in his immature consciousness, he knew that asthma was relatively trivial. There were kids with cancer in the same ward; some of the children he had met in the preceding week had no hair and were pallid as they struggled to hold off an enemy they couldn’t see. But this Friday night, the nurses brought in the TV and a boy and his dad – one a United supporter, the other on a drip but bedecked in a full Candy Adidas strip – confidently waited for the Reds to lift their eighteenth title. The boy’s dad had to go near the end of the game – another three siblings were waiting at home – but, despite Alan Smith’s glancing header, this was Liverpool at Anfield.

Those of us who are old enough, will never forget that moment. It was on Sky Sports recently and I broke out in gooseflesh watching it. Sitting on the hospital bed in 1989, moments after my dad had kissed me goodbye, it was hazy and dream like. Time didn’t just slow, it became sluggish and heavy.

“It’s up for grabs now!”

Tears again, the taste of salt and defeat and knowing that I shouldn’t mourn too hard but unable to stop myself. Hearing myself weep and aware of my surroundings, of the specters that hovered near me in that hospital bed.

The dance of life and death, of sport and of triumph and despair.

There would always be more league titles. And of course there was, one more, a year later. Aston Villa came close but the boy skipped out to his dad in the back garden as news came through that John Barnes’ penalty had sealed title number eighteen. We’d had a bet, you see. Car washes would probably be the currency in which the boy would forfeit but, this was Liverpool, this was their bread and butter, and as the boy gleefully received five pounds from his dad, the sky did indeed seem the only thing above us.

That boy was remembered seven years later. It seemed an age to a nineteen year old, now in university, with life a glorious smorgasbord of possibilities. Seven years without the league title. How was that possible? The Souness years, the decline and fall, Ruddock, Dicks and Piechnik, Rosenthal’s open goal; all were about to be forgotten as the new power, the behemoth that Manchester United were becoming, arrived at Anfield. It was April of 1997 and a win against the champions would surely see us with a huge chance of winning what was already being talked about as that elusive Premier League title. David James steps forward. Disaster. 3-1 and we meekly retreated back to our dreams, now gaining the sheen of just that. One epic drinking session later and the hangover seemed to stretch on for years.

At the age of 32, that bright eyed boy was a distant memory, as was the league title. But in 2009 we were in it again as Rafa’s best side danced with possibly Ferguson’s best United iteration. Benitez had, of course, secured memorable trophy wins but, oh, how we craved the league. The Mancs could overtake us in league titles. How was that possible? We tried, by Christ, how we tried and there were moments of sublime glory. I will never forget my 32 year old self, in the midst of a horrible break up and struggling to hold on to a teaching job because of this, as a Benayoun shot gave us a late 1-0 victory in the dying embers of a contest with Fulham in late April. Delirium, absolute delirium in the pub. That man, now grappling with the reality that life could bite hard and leave you a bewildered and fragile mess, danced the night away, sure that it was finally our time.

It wasn’t. The dance continued, that dance that seemed our lot in life, that dance of triumph and despair.

Life was good again in the spring of 2014. I was about to be married and it was our engagement weekend (my girlfriend had long succumbed to my obsession by a sort of benign osmosis). Coutinho swivelled and scored against Manchester City and for the first time in a quarter of a century, the Reds made me cry. I sank to my knees and sobbed in the middle of a heaving pub in Dublin. The title was finally ours.

Tears after Stevie’s heartbreaking fall? None, I was just numb, a state of being that probably lasted – in a sporting sense – for a year or two.

And finally, as I type these words in the summer of the surreal of 2020, as I look out the window at ten year olds playing in their Liverpool strips, now sleek and unforgivingly tight (at least for a middle aged man’s body) I still can’t fully process it. The journey we’ve all made. When Chelsea defeated City a few weeks ago, when Jordan and Jürgen cried live on air, I wept myself but it didn’t really sink in. Because of that dance, that dance of tragedy, of life, of death. Of triumph.

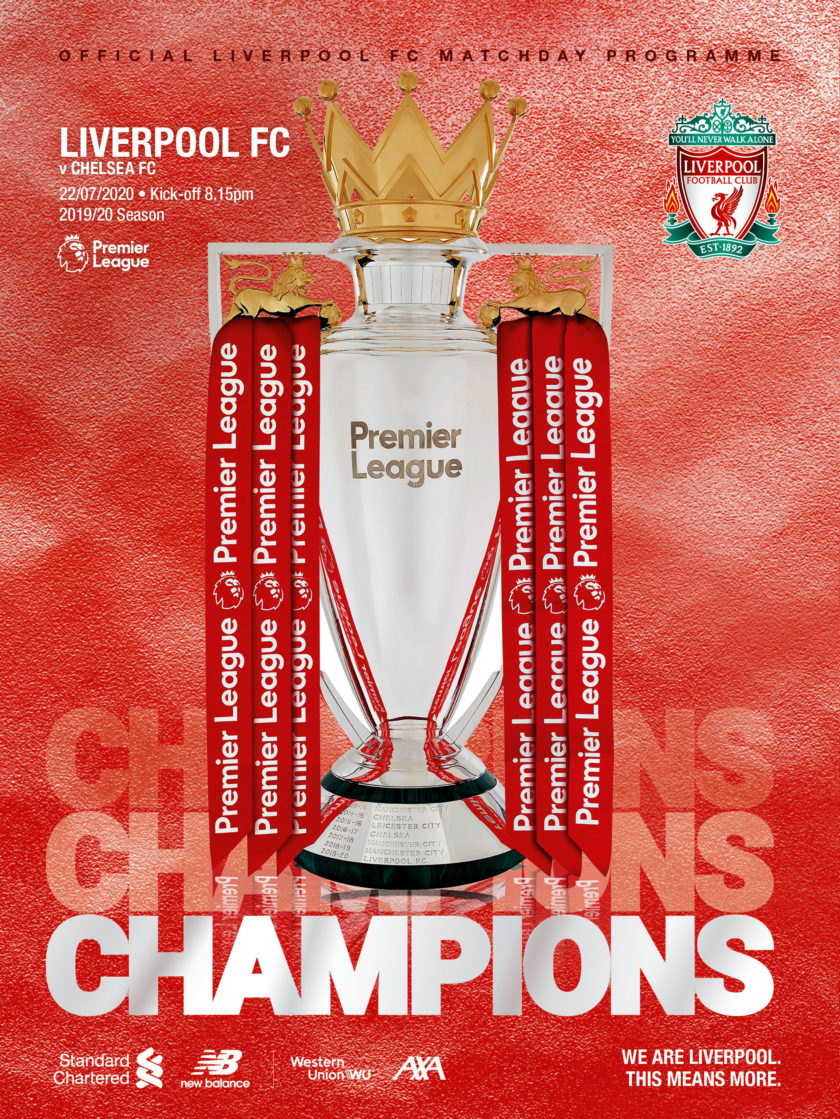

Only now, after lying awake for much of the night and knowing that this evening we will lift the Premier League title, can I start to really celebrate. It’s ours, number nineteen. The world will bounce back, the delicate equilibrium will be re-established. Humanity – in all of its glorious and brilliant fragility – will win out.

The dance will go on.