The argument against Financial Fair Play – the breaching of which has seen Manchester City banned from the Champions League for two seasons – seems to be that it “allows for fairytales”. I’m not quite sure what fairytales people like to read to their children at night, but sportswashing, underhand payments, deception, mocking the dead and human rights abuses don’t seem particularly wholesome.

Cinderella was not the story of one woman pretending her shoe size was totally different in order to give her an advantage over 19 other women in the race to becoming a princess. She doesn’t get caught out for cheating, and then lie about it. She doesn’t laugh via email when one of the dwarfs dies (or am I mixing Disney stories here?), and say “six to go”.

And remember, a success story – of any kind – where someone shits on everyone else is hardly a tale to warm the cockles.

And let’s face it, are PSG a fairytale in France? All I keep hearing is that FFP stops fairytales. Has PSG’s obscene investment made the French league a better place? From the outside it seems like PSG fans win, while the fans of all the other clubs lose as the league becomes a mockery. How is that good for the sport? Surely if UEFA were able to have PSG rein things in just a little, then maybe French football would be worth watching again? PSG are strangling the life out of Ligue Une, and it would be even worse without FFP.

Also, there’s the argument that FFP stops wealthy individuals and groups from revitalising struggling clubs. There’s only one problem with that – it’s clearly bullshit.

FFP allows for an absolute ton of investment in the infrastructure of a club (although City had already gained their stadium on the back of tax-payer money).

Owners are allowed to give fans, players and staff world-class facilities without falling foul of the rules. What more do you want? Owners can take any run-down stadium, any subsiding training ground, and totally transform them, without falling foul of FFP.

And while facilities on their own won’t win you trophies, they are solid, tangible aspects of a club, that can pass the test of time; that can stay standing long after the owners have scarpered off to the Cayman Islands. If you play at a wooden stadium and train on a boggy marsh, you won’t be able to attract the same level of player – even if offering the same modest wages – as you would when playing in a fantastic stadium and training at a top-class complex.

The notion that facilities and infrastructure has no positive effect is ludicrous. It gives a club a non-financial selling point to both fans and players.

Then, all you have to do is keep the wage bill healthily proportionate to turnover, and over time, improvements on the pitch can allow for a virtuous cycle; more money earned, more money invested back into the team; and as the facilities have already been improved (a new stand, a new stadium), you can get more people in to watch the games. (Almost as if that’s the way Liverpool have become the best-run club in the world.)

City have, all the same, invested incredible sums in the facilities, such as their monstrously expensive academy – £200m back in 2014 (which, if inflated in line with transfers, would be £450m) – but it seems that this was not enough. Corners, it seems, had to be cut.

Why?

If it was about purely sporting intentions, then time is all part of the equation. Time should always be a part of any sporting equation.

If it’s about sportswashing, there’s no time to waste. Time is what sprinters have to put in, to get to the top, training day in, day out, for months and years on end, making sacrifices along the way; doping is what sprinters do when they want to jump the queue, or what fat sloggers take to hit a baseball further.

In time, if you build wonderful stadia and world-class training grounds and academies – even at the kinds of massive losses allowed by FFP (so, just like City were allowed to do by spending £200m on an academy) – you can begin to compete at the top end.

(Obviously you have to then play some of the lads from the academy at some point; unless you are so rich that you don’t even need to do that.)

But that all requires patience and expert planning. City’s owners could still have turned the club into a hugely competitive, world-class institution without all the things UEFA have found them guilty of doing – either originally (which resulted in a fine and a squad reduction), or in the deceptions that followed – and they still might have won the league once or twice; at the very least they could have qualified for the Champions League through legitimate investment, and built a base from there, like everyone else has to. Having been in the lower leagues not so long ago, wouldn’t that have been a fairytale of a kind?

It wouldn’t have guaranteed the league title, but who the fuck has a right to that anyway? The argument that FFP stops clubs from growing and denies fans improved football is an utter straw-man. Fans can still dream of good facilities and good football – take Norwich City, Southampton, or before them, Swansea City. It may not last forever, but these are not clubs for whom winning the league has ever been a legitimate goal anyway. Wolves are competing for Europe, whilst playing in Europe. They’ve had a lot of investment, but all of it within the rules, as far as we know.

Success in football is mostly about the successful husbandry of resources – sacrificing one thing to focus on another – that makes so much of the process a big compromise. If you can just cut out all the compromises, such as never having to sell a player or lose a manager because of illegally inflated sponsorship deals and hidden payments, then everyone else who is sticking to the rules gets shafted. You then squeeze them out of the equation. Everyone else suffers.

One of the big issues I have with Miguel Delaney’s recent argument about the age of the super-clubs – which is otherwise sound (indeed, I was banging on about the widening financial unfairness of football over a decade ago) – is that Liverpool, whom he holds up as just another super-club, had spent virtually all of the 2010s ranking as the 5th-richest club in England, and qualifying for the Champions League just once between 2010 and 2017/18. Liverpool’s starting point, even in 2018, was really lower for a “super-club”.

Yes, Liverpool had a massive name, and were a sleeping giant, but as other clubs have shown, you can’t easily awake a sleeping giant if you are not petrodollar-charged. Look around, and there are a ton of sleeping giants all the way down the pyramid. What Liverpool are doing now is of course in part possible because of things that happened in the club’s past, which accrued a large and loyal support base; but past glories are not helping Nottingham Forest, Leeds United or Preston very much right now. And is FFP holding back Newcastle from being a bigger club, or is it their owner, and their current manager (with Newcastle now having the worst numbers in the league on almost every metric)?

And when Leicester City had their remarkable success in 2016, no one was sneering “but why can’t a club like Dagenham & Redbridge be champions?”, given that Leicester, in relative terms, had innumerable financial advantages over a hundred other clubs in the pyramid.

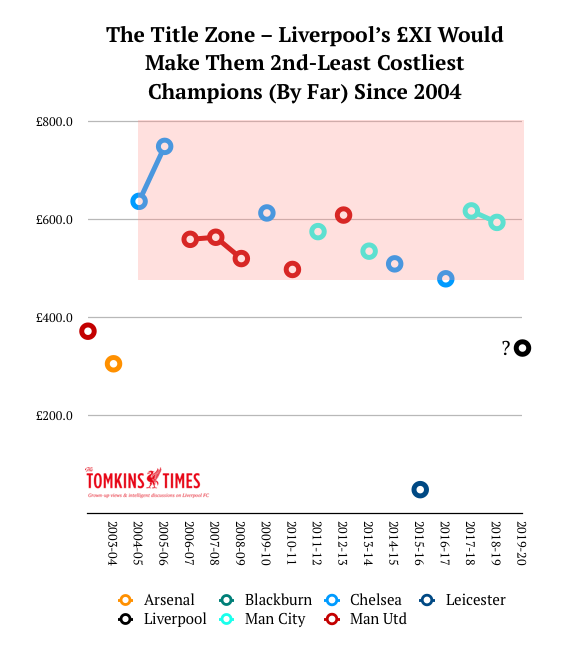

Even now, based on £XI (with the £XI being the average cost of the starting XIs across all 38 games, adjusted for inflation, as used in our Transfer Price Index work since 2010), Liverpool would be the cheapest winners of the Premier League era, bar Leicester, in terms of the financial gulf to the richest team; even Chelsea at their richest had Manchester United within roughly 70% of their financial clout; Liverpool are currently well below that in terms of the gulf to City’s £XI, and even Man United, who rank 2nd, have fallen to 68% the cost of City’s £XI, having been neck-and-neck with them until just last season. (Although United’s overall squad costs, after inflation, are over £1.1billion, with City’s at £1.3billion. Liverpool’s are just £770m – still a lot, but nowhere near the cost of most of City, United and Chelsea’s squads in the past 15-20 years.)

So, to say that Liverpool are just part of the established global elite is to ignore that, when FSG arrived in 2010, the club was close to going into administration, and between 2010 and 2018, was routinely forced to sell its stars due to predatory clubs, which in part led to an inability to reach the Champions League, which was a pathway in part blocked by Manchester City, at the time City were said to have broken the rules (let alone City denying Liverpool a title, although I wouldn’t expect that to be retrospectively awarded to the Reds – although maybe after this season is sewn up, it can be revisited. If City’s titles were to be rendered null and void, and no one was the champion, then what about all the fans of the clubs who paid to see their teams in those seasons, if those seasons are now said to be “shams”? What about all the losses of earnings for Liverpool and Manchester United when finished 2nd to City, or the clubs kept out of the top four? It all has a knock-on effect, which is why it’s so nefarious).

While Delaney – a critic of City’s approach – accepts that Liverpool’s rise has been in no small part due to the club being brilliantly run and managed on the pitch, it was never an automatic case of it just happening one day; after all, we’d waited almost 30 years, and other big clubs remain lost in whole worlds of hurt. Not everyone’s chance comes around again.

And while it would be nice if the league had the varied competitiveness of previous eras, it seems odd to really fixate on Liverpool when, between 1992 and 2019 – but especially between 2004 and 2019 – far richer clubs were routinely winning the title.

The cost of this Liverpool team is still well below the historical Title Zone, which I’ve been talking about for many years now – where all the £XIs of all champions between 2004 and 2019 (bar Leicester) cost well in excess of the Reds’s current figure. Manchester United, Chelsea and Man City’s £XI in that time – when all converted to current day money – far outstrip Liverpool’s current £XI.

The last Title Zone graph I produced was earlier this season, and it’s in 2019 money. As you can see below, Liverpool’s £XI this season falls well below the shaded Title Zone.

And even then, Liverpool’s success has still been in no small part built on selling Philippe Coutinho, amongst others. Liverpool could not afford to keep Coutinho and buy both Virgil van Dijk and Alisson Becker. Imagine how much better the team could have been had they managed to have all three at once? (It might not have been, of course, but the chance to see would have been nice.)

Liverpool had to take a risk, in selling a player seen as unsellable; and, had it gone wrong, the backlash would have been clear (but hindsight bias makes people forget about the existence, at the time, of that potential outcome).

That £142m injection – along with the proceeds from the unexpected run to the Champions League final in 2018, having sold Coutinho halfway through that season – have in many ways funded this success. All of it is within the FFP guidelines, following the rules.

Indeed, FSG never promised money the club didn’t generate; aside from loans – which are permitted – to help rebuild the Main Stand, it simply promised to run the club better, and help it generate more money, that would go back into the team. It promised not to saddle the club with debt, and it has stuck to that promise. They stuck to the established fair and proper ways to run a football club, just with added intelligence. And even then, they made mistakes; but honest mistakes.

When they made mistakes, such as reinvesting two-thirds of the Fernando Torres money on Andy Carroll, the club was condemned to more time in the wilderness, because they could not just go and spend £200m on three other players to cover the gaffe and spread the risk.

As it was, Luis Suárez arrived at the same time as Carroll, but it took years for him to help shoot the Reds into the Champions League. (Jordan Henderson was seen as another costly flop in 2011, but he could now captain the Reds to unprecedented glory.)

Then Suárez wanted out.

Liverpool could not stop him from joining Barcelona, because they could not offer regular Champions League football, nor could they pay the wages Barça were offering (in addition to the lure of the country and the climate).

When Suárez finally got his way, and jumped ship – and in fairness, it was a good sporting move for him – he was getting out of a club playing catch-up with City, while City made all these alleged dodgy deals. Were Liverpool supposed to cook their books too, to make it all work? What if your owners – whilst wealthy – aren’t the richest people in the world, and only bought the club because of the promises – made by UEFA – to make the sport less financially dopable?

With the money from the Suárez sale, Liverpool had to rebuild again. As with the Torres money, some of it was wasted, but one of the biggest successes was Emre Can, who – because Liverpool had to stick to the wage structure – left to join Juventus, for much more money. How many key assets have walked away for free, at a prime age, from City?

(As an aside, Dejan Lovren and Adam Lallana played reasonable roles in moving the club forward after Jürgen Klopp arrived, and Divock Origi, while still not consistently good, must have paid his transfer fee ten times over with the bonus earnings the club has made on his goals.)

How many key players have City lost to Real Madrid or Barcelona? Or even to other Premier League clubs? None. If you are never in danger of losing your players you have a massive advantage.

City essentially preyed upon Liverpool, given that City were – to a reasonable degree – keeping the Reds out of the Champions League; they could then afford to buy Sterling, pay him huge wages, and offer him the chance to play in the elite continental competition. That then helped make it even harder for Liverpool to get into the Champions League.

Now, lest I be accused of hypocrisy, Liverpool prey on other clubs, such as Southampton; but Southampton prey on other clubs, such as Celtic; and Celtic prey on other clubs … and so on.

It’s a food chain. It’s how it’s always worked.

As with Suárez a year earlier, you could not argue, on sporting grounds, against Sterling going to a club that could offer more – unless what City were offering was something their illicit payments were helping to achieve, that made it an unfair fight; or rather, even more unfair than the natural food chain dictates. (No one said these things could ever be utterly egalitarian.)

But it’s been a long road for Liverpool, with almost a decade spent in City’s shadow; and if City’s huge shadow was cast by shady activities, then obviously we’re going to be pissed off, just as you’d expect if the roles were reversed. If it came to light that all Liverpool’s finances were corrupt, everyone else would go mad. But that’s not the case.

Liverpool lost great players in part because City were gaming the system, and as such, Liverpool fans suffered the consequences. Our “fairytale” was Roy Hodgson, Charlie Adam, Christian Poulsen, Milan Jovanović, Joe Cole and the rest of the dross or has-beens that worked their way through the club on account of an inability (at that time) to pay big fees – unless someone better was sold – and sustain high wages.

Liverpool’s general lack of European qualification – and lack of progress once qualified – between 2010 and 2017 meant that when the Reds did get back in, it was with a low coefficient. So it was one more thing the club had to overcome; something for which a rich history did not come with bonus points.

If it turns out that City were essentially successful – making new money – on the back of a kind of financial cheating, then that is akin to someone “legally” making interest in one bank off the £1m they stole from another. If City’s initial success was achieved by underhand means, then that granted them a share of the Champions League and Premier League prize money that allowed them to fund the rest of the operation, at the expense of others. If Ben Johnson had spent his life living off the interest of victories achieved whilst doping, that’s hardly deter cheating. Equally, if Johnson, on account of his juicing, was entered into an elite stream of competitions that garnered him massive annual rewards, that would make zero sporting sense, and harm the chances of all the non-juicing runners.

If City had achieved all their success legally, in terms of the rules they agreed to adhere to, then there could be no arguments. We wouldn’t like that they had the richest owners around, but what can you do about that? We don’t like Man United’s wealth, but it all seems legally accrued.

But City, as it was with Chelsea the previous decade, were keeping Liverpool – and others – out of the upper reaches of the league. It stung when Man United did the same, but they gained their wealth through being a big historical name that timed its newfound success with the newfound riches on offer; allied to excellent marketing and merchandising, which most Liverpool fans looked on at with envy. (All fans seem to hate the tackiness of marketing and merchandising, whilst at the same time wanting that revenue.)

And of course there should be something in place to stop the Glazers from acquiring United in a leveraged buyout, then saddling them with debt; in the same with George Gillett and Tom Hicks fucked over Liverpool. But in both cases, FFP was allowing clubs to self-harm (or be harmed by their “parents”), which has no relation to what City are accused of; and indeed, Liverpool (up to 2010) and United having financial leeches should have given City even more leeway to succeed without having to breach FFP. United were – still are – throwing away tens of millions of pounds a season on interest on debts the owners saddled them with. That, in turn, helps City, just as it helps Liverpool.

Much of Liverpool’s decline was self-inflicted, starting in the 1990s, and when Roman Abramovich financially doped the living shit out of Chelsea he was entitled to do so, as FFP was not in place.

So as much as I hated the way Chelsea were able to act, it was not a breach of the rules. It just made it harder for everyone, including even the mighty Manchester United, to compete; although United started to match Chelsea’s spending, as the only club capable of doing so. That said, they made two sales – David Beckham and Cristiano Ronaldo – that brought in over £500m in current-day money (£300m of it for Ronaldo), to reinvest in players, which was something Chelsea never had to do. To this day, they are two of the top four most profitable sales in the Premier League era.

And while City weren’t solely to blame, Liverpool’s drop from the top four in 2010 coincided with the Citizens own cash-injected rise; which essentially meant there were now just three Champions League places on offer to everyone else, as long as City didn’t self-combust. Liverpool’s attempt to get back into the top four was made harder by one of the teams already in the top four being found guilty of disobeying the rules.

The fact that Man City agreed to obey FFP in order to play in UEFA’s own competition seems lost to a lot of people. You can’t agree to drive at 20mph near a school, and then drive at 47mph when there are no speed cameras around; even if you think there should be no speed rules, as it’s 100 yards down the road from the school. To say that UEFA should not be in charge of their own rules is absurd.

The excellent Mancunian David Conn, on the latest Guardian podcast, said that the issue this time with City – even though it relates to the FFP breaches of a few years ago – is more about City’s deceit, and using a similar metaphor to mine above, stated that if you get done for speeding you get three points on your licence; if you lie to the police, and say that your partner was actually driving, you go to jail. Hence, the crux of this case is the seriousness of the deceit; and if you are finding someone guilty of deception, then by default you can’t say that everything else they are doing is to be trusted.

Now, I can’t claim to be an expert in City’s finances, nor the vagaries of the case against them – beyond what I’ve read from reputable sources. And no one seems to know what the game-changing evidence City allegedly have, waiting to blow a hole in UEFA’s case, other than promises to outspend UEFA on lawyers and tangle the case up in red tape, which seems wonderfully sporting.

But what I can do is show how their financial doping has made it harder for everyone else.

And so, the fairytales. There has been only one true fairytale in the entire Premier League era, and that happened after FFP was in place. While Leicester winning the title was a moonshot, they are ten points clear of the chasing pack in the top four. By being well run, and from having unexpected on-field success, they have funded the building of a stronger, self-sustaining model.

They won the title with the third-cheapest £XI in the Premier League in the 2015/16 season – costing about 15 times less than the Manchester clubs that season – and it remains by far and away the cheapest side to win the title in the modern era. It was a one-off; but it didn’t happen prior to FFP, in part because Chelsea and Man United were too rich too fail. (If one had a bad season, the other did not.)

You cannot bank on Leicester’s type of success; but as of the 25-game mark in 2019/20, they now rank 9th, with an £XI – at almost £150m – that is roughly three times the cost of their title winning team. They’ve gone from ranking 18th to being in the top ten. They are now outsider-contenders.

It’s still nowhere near the bigger clubs, but it’s competitive. If Leicester winning the league is not a fair standard to hold others to – given that it was so freakish – then Leicester finishing in the top four twice in five seasons certainly is. Because clearly they are doing something right, beyond sheer luck, that bigger clubs like Newcastle, Aston Villa and, in the Championship, Leeds United are not doing.

In a highly surreal explanation of why FFP isn’t fair, Gary Neville – talking as an owner of Salford, who have not been subject to FFP laws – said on Sky that FFP stops clubs like Leicester doing what Leicester have been doing; or words to that effect. Isn’t the whole point that Leicester’s owners invested heavily but within the FFP limits? And that, over time, they experienced success?

(That said, Leicester did pay a fine for breaking the Football League’s FFP rules. But that’s another issue; as far as I know, they haven’t done so since being promoted, and their spending doesn’t look unusual with regard to the financial rewards they’ve accrued from winning the league and reaching the quarter-finals of the Champions League, whilst also selling a lot of their stars for big money.)

And while financial might obviously correlates with success, Leicester will have had a far more successful five years than Manchester United, who have spent gazillions more. FFP has not stopped Leicester from giving us the greatest fairytale of all, and having a couple of decent sequels, too.

Wealth Comparisons and Inflation

For all City’s wealth, the costliest team and squad, after inflation, remains Chelsea’s 2005-2007 era. When people talk about the most expensive teams ever assembled they ignore inflation; just as £66m for Alisson Becker, followed by £72m for Kepa Arrizabalaga, pale in comparison with over £250m, which is the rough cost of Gianluigi Buffon’s move to Juventus in 2001 when adjusted to current prices.

(Just to explain, football inflation runs a lot faster than standard inflation; in the Premier League, the average cost of a player is 30x higher than it was in 1992, whereas “normal” inflation has only doubled. All our football inflation is based purely on Premier League spending, so it’s just an estimate to apply it to Serie A.)

Just how much did it cost Liverpool, being out of the Champions League? In many senses it can be seen in the fees received for the players they could not hang onto.

And of course, one of the players Liverpool lost – Raheem Sterling – was to Manchester City. An inability to be able to hold onto Suárez was a link in the chain on the way to Sterling also departing.

Adjusted to 2020 money, Raheem Sterling cost City £109.8m.

Since that move in 2015, inflation has seen player prices more than double, although the process has not been linear; in 2018 money he would have cost £106.9m, but in 2019 money there was actually deflation – as tends to happen once every five years or so (or more frequently if the TV market bottoms out). A rise again this season means prices are up to their highest ever level, although only fractionally over the 2018 values – the season when Liverpool paid £75m for Virgil van Dijk (as such, that £75m is still less than £80m now).

Adjusted for inflation, Liverpool’s most expensive player right now is Alisson, at £85m, given that £66m in a deflated market equates to more than £75m in an inflated market. Even so, City have five players who cost more than Alisson when adjusted for inflation, and most of them date from around the time of City’s FFP infringements. I’ve seen arguments from City about how they haven’t bought the most expensive players, but of course they have, as that’s how inflation adjustment works. (Just as Star Wars didn’t gross as much as many average-grossing films now, given that cinema tickets were much cheaper in the 1970s. Obviously.)

Agüero, £163,292,032

de Bruyne, £123,189,716

Sterling, £109,750,838

David Silva, £89,082,527

Fernandinho, £86,677,744

City have 16 players in their squad who cost £45m or more in 2020 money. Liverpool have roughly half as many, at just nine. The 19th most expensive player at City, Claudio Bravo, cost £26m in 2020 money; Liverpool’s 15th-most expensive, Xherdan Shaqiri, cost £17m after inflation. Next comes Andy Robertson at just over £10m, and by squad position number 20 the Reds are on free transfers and home-grown freebies. City’s squad cost 85% more than Liverpool’s.

So, to not apply inflation – and pretend City haven’t paid big fees – is to ignore the massive spending that City agreed to as far back as when paying £162m for Sergio Agüero, or £123m for Kevin de Bruyne.

And these are just the players they kept. Eliaquim Mangala, at well over £100m, cost almost 50% more than van Dijk, when adjusted to 2020 money. This is the luxury of never having to sell players to buy players, as Mangala was written off like a man crashing his Ferrari when he has 50 more back in his garage. C’est la vie.

When Liverpool had their own über-costly mistake – Andy Carroll, at almost £130m – the club had the scrabble around for cheap strikers, as the money was gone, and Carroll was a liability. My argument against financial doping is that it allows clubs to stockpile expensive mistakes and offload them with impunity, keeping only the successes; using my old “Tomkins’ Law” as a rule of thumb in that roughly half the buys will work out (based on a study of over 3,000 signings in the Premier League era) and just discarding the rest with no adverse consequences. That’s just loading the dice. It’s not clever, nor is it fair on other clubs, nor the players who get stockpiled.

And remember, it was just 2018 when Liverpool were last scalped of a world-class player. No club chooses to be a selling club; the market just does that to them. For the first decade under Abramovich, Chelsea never had to sell its players; but in 2019 they sold Eden Hazard for a fee that, while initially £89m, could exceed £150m (and with the Transfer Price Index, Graeme Riley and I always calculate the maximum amount payable).

That’s how it works when not financially doping.

While I don’t have all the sales fees converted to 2020 money, in 2018 money (which was just a couple of percent less), the Reds have five of the top 25 outbound transfers, and all from the last 11 years. All the players wanted out; Xabi Alonso while the cowboys were still owners, and Torres, Suárez and Sterling all following the near-implosion of the club and its tentative rebirth under FSG, and Coutinho leaving just before it was clear Liverpool were going to be something really special. All of these sales were forced on the Reds, and all meant rebuilding the team.

Ranking 70th is Javier Mascherano, sold for a baffling £20m by the cowboys, which now equates to £70m.

That’s six world-class players lost in eight years (excluding melters like Pepe Reina, Jamie Carragher and Steven Gerrard), in some cases because Liverpool could not get back into the top four, with City blocking their path. Liverpool’s wage structure – within FFP guidelines – meant they couldn’t just offer to double someone’s money to keep them; or would not make iffy payments in paper bags.

Manchester City have only one expensive sale in their entire Premier League history: Shaun Wright-Phillips, who ranks 11th since 1992 at £153m. Prior to their Sheikover, City only had one player really worth selling.

But more tellingly, since the Sheikover, they haven’t had to sell anyone, despite having about 30 players worth selling for big money in that time.

The only reasonable fee they’ve received since the Sheikover was for Mario Balotelli, at c.£75m, and he was someone the club wanted to get rid of. He doesn’t even rank in the top 50 for inflated sales figures. Robinho, the first buy of the new era, was bought for over £100m in current day money and sold for half that. Emmanuel Adebayor cost over £100m, left for a fifth of that. Carlos Tevez cost over £100m, left for less than a fifth of that. Successes or not, these losses of fees were easy to overcome. At first it was possible because of no FFP; but then FFP stopped clubs spending so wildly, and clamped down on the writing off of big losses in the market.

Edin Džeko, Joleon Lescott and James Milner each cost City over £90m (almost £300m combined), and recouped a grand total of just £14m. Other clubs could not afford to operate like this, and if people think this is “fair”, I don’t understand that. It’s a disposable culture; writing off Ferraris.

Indeed, the way Chelsea have had to change the way they are run – their £XI dropping steadily over the past decade, as their compliance with FFP becomes clear – shows that it’s not fair on others if they stick to the rules and City don’t. And obviously my heart will never bleed for Chelsea, but if they’re sticking to the rules, shouldn’t City? If all the clubs are being honest with UEFA, why should City be different?

Whilst Chelsea’s £XI has massively dropped – mostly in the past five or six years – they have still won the title twice, and still often finish in the top four. They are sportingly competitive now, in the knockout rounds of the Champions League and in the top four in the Premier League; not doping the hell out of the league. It hasn’t turned Chelsea into anything other than another serious contender, rather than being so far ahead of everyone else in wealth that the league title was theirs half the time if they wanted it. This is good for competitive balance, surely?

Speaking on the generally excellent Second Captains podcast (probably the best non-Liverpool podcast around), Richie Sadlier was making the point that City will struggle to hold onto their best players because those players had been “sold” to the club on the grounds of Champions League action, and will have bonuses linked to it. It was a fair point. However, one of the presenters was arguing that City could still choose to honour those bonuses – which, by contrast, seemed to miss the whole point.

If City are to be without the Champions League for two years (and all the TV money, gate receipts, legal sponsorship money, etc), that’s a potential loss of £100m per season. If they can only just about currently pay the wages with financial chicanery – if the sponsorship deal is still inflated, which may be possible given the financial shitstorm that is Etihad’s finances (“Etihad Airways posted a loss of $1.28 billion in 2018, extending the deficit over three years to $4.8 billion” – Bloomberg) – then they sure as hell won’t be able to afford to pay them when they are denied one of their biggest revenues streams. On top of that, if Etihad then upped the sponsorship to cover the shortfall, that just brings City back to a further ban, as any sponsorship would be worth less without the Champions League, not more. Again, at least in terms of the ban, UEFA say that City are guilty of being totally untruthful.

The best news of all, as a Liverpool fan, is that the Reds have overtaken City before City’s punishment. To be honest, I assumed that, just as with Chelsea a decade earlier, the chances of Liverpool finishing above City were remote. City fans were trying to call Liverpool’s title charge “tainted” because, on average, the Reds have now had a “for/against” balance of one VAR decision overturned (whereas other clubs are in credit to seven overturns in their favour), yet City’s 2013/14 success is the one that clearly looks tainted; and that success brought in “legitimate” – or laundered – finances to get stronger still.

(And remember, as an aside, there was a Mancunian referee and a Mancunian VAR giving Manchester United two unbelievable decisions last night, and with other referees from Manchester also allowed to officiate for them, Liverpool are not allowed to have Mike Dean, who supports Tranmere, unless Liverpool are playing Everton. Imagine the outrage if Liverpool had Scouse referees and Scouse VARs giving them massive decisions in huge games!? Liverpool often have to play both Manchester clubs with a referee from Manchester. The big game at the Etihad last season saw Anthony Taylor of Manchester not send off Vincent Kompany, for what everyone agreed was a blatant red card offence. This handed the title initiative back to City. Again, imagine if Mike Dean had done that at Anfield in the reverse fixture! Imagine if a Scouse referee let Liverpool players kick opponents in the balls, and the Scouse VAR said “on you go!”)

Pep Guardiola is a brilliant manager, and the team he produced played amazing football. But if it was aided by underhand payments or lying to UEFA about income, then it enabled them to build a bigger squad with greater depth and more world-class talents, and pay higher wages to retain those world-class talents (and keep all potential predators at bay), then it was gaming the system. As it was, much of City’s current legal wealth has been accrued by gains made from the period where they were fined but not expelled from the Champions League (in part because a special deal was struck with Gianni Infantino, then the head of UEFA).

All of which highlights how brilliantly Liverpool have done, to go from 5th in the financial rankings up until very recently, up to 3rd, based on the steady – and then explosive – on-field progress made under Jürgen Klopp (spending bigger only followed earning and selling bigger), and to overachieve even with a squad that costs 60% of the Mancunian Rich Two. (Until this season there was a clear Rich Three, but Chelsea have really cut back.)

Ultimately, whatever punishment City will face will be because of the rules they signed up to and broke, and how they deceived UEFA in the aftermath. If all of this is true – and let’s remember, whilst everyone utters “allegedly” in fear, they have been found guilty – then who is to say what else they do to sway the odds in their favour?

(Note: if City are later found to be innocent of these charges I will gladly retract or update this piece. However, we don’t say that convicted killers are “allegedly” guilty, even if they wish to appeal. Innocent until found guilty, and then guilty until further notice.)