It’s always wrong to think you have won the transfer window; remember Everton in 2017? But looking back, did that even make much sense at the time (other than to Richard Keys), buying three slow no.10s? Had anyone seen Wayne Rooney – once without doubt the best British striker, by then a plodding midfielder – play since 2015?

It’s wrong to pre-judge signings, but what you can do is try to assess the suitability and quality of those players when compared to the requirements, and how they might mitigate any shortcomings. You can’t predict injuries (unless they are recurrences of old ones), nor how players will settle, adapt and learn the language. (Although the climate in England is not an issue right now.) So you can only base it on what you know about the new signings and how you see their potential unfolding, without the aid of a crystal ball.

To me, the benchmark for Liverpool is always 1987, when four key players were signed between January and October, at a 100% hit rate. And not just a 100% hit rate, but where Ray Houghton was a clear success (busy midfielder weighing in goals), John Aldridge scored a ton of goals (albeit a fair few penalties, in the glorious era when Liverpool still won penalties), Peter Beardsley took the team to a new level, and best of all, John Barnes was a generation-defining player in the English game; the kind of player you are lucky to sign or find once every ten years.

I tend to mention 1987 at this time of the year, as I look at the general state of Liverpool’s transfer business, and add the context of the Transfer Price Index that Graeme Riley and I created to convert all transfer fees in the Premier League era to modern day money. Obviously 1987 predates that, but it remains the benchmark on how to do business.

This year has the potential to match 1987; although if you made it an 18-month period, and included Mo Salah and Andy Robertson, it could perhaps be hard to beat in terms of quantity and quality.

(As an aside here, Bob Paisley still remains the master buyer of Liverpool’s history, with an astonishing hit-rate with his signings, almost all of whom were not established world-class players before arriving, and many of whom were aged 19-24. But in some seasons he only used 14 or 15 players, and so mostly it would be one or two signings a year for the first team, and maybe a youngster here and there. Squad sizes are now easily double what they were back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, and so logically, you usually need to sign twice as many players these days. Indeed, perhaps even more than that, as a) there’s more freedom of movement for players, ever since the Bosman ruling of 1995, and b) the greater number of foreign players means a more transitory nature – players may try a couple of years in the Premier League before wanting a new challenge, whereas 99% of British players have always stayed within the British game, and therefore, more time would be spent at each club, given fewer opportunities to move.)

You also have to analyse the recent history of the club’s transfers, and how successful they were proving, which may give more cause for optimism (if it shows there’s an actual plan in place in terms of what to do with the players when they arrive); are they exceeding Tomkins’ Law, named by Dan Kennett after I analysed 3,000+ Premier League transfers for the success rate of all those transfers. By my calculations, roughly 50% “succeeded” out of all the deals, using a fairly objective – but not foolproof – set of criteria based on games played and/or resale profit, but even the most expensive deals rise to a success rate of just 60%.

Everyone could see that Virgil van Dijk was, to an impeccable degree, exactly what Liverpool required, although he arrived without having played much football for a year, and there was still the obvious risks involved, in terms of the pressure of playing for one of the biggest clubs in the world, and the weight of the fee, neither of which had affected him before. (Celtic are a big club by certain standards, but exist in a small league that is not followed internationally, and they have little European pedigree since 1970.)

Remember, other nailed-on successes have flopped badly; just think back to how it seemed that Chelsea (at least to me) would be unstoppable with Andriy Shevchenko and then later, Fernando Torres. But that was Chelsea buying superstars who could easily have been beyond their peak; megastars whose sharpness was dimming and whose hunger was perhaps not what it once was.

Perhaps big-money signings are generally succeeding more than in the past (although this is something I need to go back and look at in more detail), as clubs have generally wised up to actually integrating those players – even if’s still no guarantee.

In the 2008 book Soccernomics, there’s the story of how Real Madrid made zero effort to help Nicholas Anelka settle back in 1999, having spent a fortune on him; not even assigning him a locker, so that whenever he went to put his stuff in one locker another player came along and asked him to move it. Perhaps clubs now do too much for players, creating man-children who can’t even open a bottle of water for themselves. But they don’t just leave multi-million pound assets to sink or swim. (On this last point, this can of course be character-building. Also, it can lead to drowning.)

In 2018 money, based on Premier League inflation, Anelka cost Real Madrid £210,061,893 (I’ve copied and pasted the figure from the database for this article, so I’m not trying to make a big deal of the accuracy to the last pound). This is the third-highest figure in the entire database, and all three of those figures are for exporting players at a cost higher than the Premier League had ever paid for an individual. (Cristiano Ronaldo £336,568,756; Gareth Bale £241,326,808; Nicolas Anelka £210,061,893.)

Last summer Ronaldo was around the £200m mark, which is also what the world transfer record in actual money ended up being when PSG bought Neymar. British and world records tend to jump more sporadically, sometimes not being broken for a few years; but all the while the average can be rising. Inflation for last season was at over 40%.

At this point it may be worth reminding you that each year with the Transfer Price Index we take the average price of all players signed by Premier League clubs and that forms the index, and this tracks inflation. (Many of you will know all this, but it’s worth including a brief explanation each time I write about it.)

The more a player cost in relation to the overall state of the market in any given season, the greater his fee will seem in 2018 money. In particular, the players bought by Chelsea and Man United c.2002-2004 will always seem astronomical, which is because, on average, the prices of Premier League players were falling, due to the collapse of ITV Digital and the reduced Sky television deal of the time; while Roman Abramovic injected his own considerable personal wealth into the transfer pot.

As the market fell – by 20.53% in 2002/03 and another 17.20% in 2003/04 – Man United and Chelsea were the only two clubs who seemed unaffected. Remember, at this point Liverpool weren’t even able to pay half the British transfer record for their most expensive player (Djibril Cissé).

Chelsea, in particular, rewrote the rules, and the importance of factoring in inflation can be seen with how people could now argue – in the age of illogical arguments – that Chelsea’s unique, astronomical and indeed, mind-blowing spending from the time – which must always remain astronomical and mind-blowing within the context of the day – could be written off as fairly unimpressive now; like saying that the brand new Rolls Royce Phantom delivered to Princess Margaret in 1954 was actually cheap because it “only cost £8,500”; when of course it would be well over £200,000 in today’s money. To not use inflation means that a bespoke Rolls Royce limousine for royalty cost 50% less than a current Ford Fiesta. Hence, converting transfer fees to current day money is the only thing to do.

Another reason we created football inflation is because normal economic inflation means prices in our daily lives have only doubled since 1992; but the average price of a footballer is now 27 times what it was 26 years ago. When the index rises as sharply as it has in recent seasons, then there’s even a huge difference between buying a player in 2016 and 2018. (Paul Pogba cost Man United the world record fee in 2016, at £89m rising to £94m. That is therefore more expensive than a player costing £100m in the new inflated market would be.)

At the time they occur, pretty much all big-money signings tend to feel right, and sure to succeed, as the fee relates to how someone is either playing right then – and recency bias makes us judge how “hot” someone is – or had played to that level consistently in the past. There are other factors in play, but it’s rare for big-money signings to be relatively unheard of.

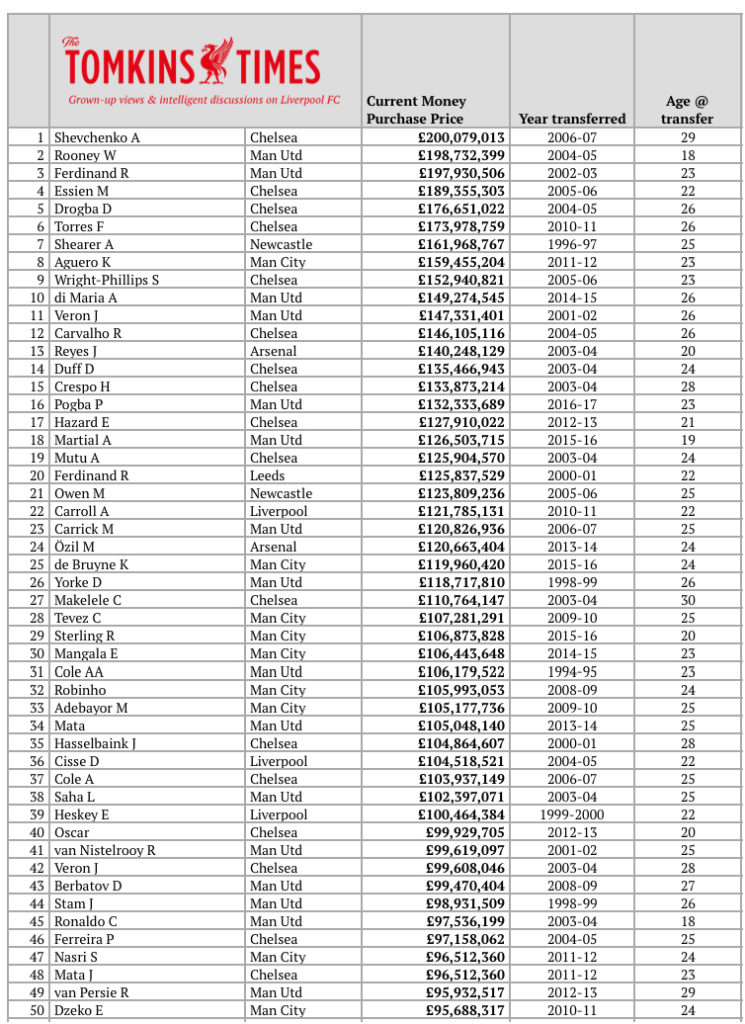

But Angel Di Maria (£149,274,545), Juan Veron (£147,331,401) and Paul Pogba (£132,333,689) are seen as failures at Man United (Pogba still has time to correct that perception), and Andy Carroll (£121,785,131) certainly failed to live up to hopes at Liverpool; although that was an unusual case of his “11th hour” fee being whatever Chelsea paid for Fernando Torres, minus £15m. Either way, it didn’t exactly work out for anyone bar Newcastle.

To further clarify, using our Transfer Price Index, “2018 money” is calculated up to the end of the January 2018 transfer window. So even though it’s 2018 money, it is based on the season, rather than the calendar year.

So anyone bought in 2017/18 has the same value as their actual transfer fee, because it’s still 2017/18 money; and obviously new players retain their actual fee. But at the end of the January 2019 transfer window we will convert 2017/18 players to 2018/19 money (while players bought in 2018/19 are already in 2019 money). So Paul Pogba’s price in 2018 money is £132,333,689, but in 2019 money (this season’s money) it could perhaps be over £150,000,000. As such, £66m on a goalkeeper in 2018/19 isn’t necessarily that expensive.

If there was a 10% rise in the average price of Premier League players this season (which in itself would be way down on last season, but I chose that figure as it makes the maths easier to explain) then van Dijk’s fee will increase to £75m + 10% = £82.5m (and Pogba’s would be £132m + £13.2m). But of course, everyone else’s fee (bar those bought this season) will also increase by the same percentage.

In other words, if football inflation was a nice round 10% every season, then someone bought for £50m would rise to £55m after a full year, then £60.5m, then £67m, and so on, with every passing year. But of course, it usually runs much faster than 10%.

Getting back to some other big buys who failed to deliver, Shevchenko, at £200,079,013, remains the most expensive player bought by a club in the Premier League era, and was a clear flop; while Torres (ranked 6th at £173,978,759) also generally underwhelmed for the Blues. Also, Hernan Crespo (£133,873,214) scored a pretty decent number of goals, but didn’t really fit in beyond that. Shaun Wright-Phillips (£152,940,821) and Adrian Mutu (£125,904,570), both of whom were bought by Chelsea, and Jose Antonio Reyes (Arsenal £140,248,129) complete the list of flops within the top 20 – which Chelsea dominate. (Andy Carroll just misses out – not because he wasn’t a flop, but because his fee is ranked 22nd.)

Adjusted for inflation (which, when done for a team over the course of a league season, we call the £XI), then even the costliest possible team Liverpool could field this coming season would not match the lowest £XI of 13 of the past 14 champions; and that’s ignoring the fact that Liverpool will not be able to field its costliest team all season, as no one ever can.

Leicester were the obvious exception, but otherwise (adjusted for inflation) an £XI of a minimum of almost £600m in 2018 money has won every title bar on since 2004; and Liverpool could top out this season around £550m.

(In order since 2004, the £XIs of the title winners, in order: £778.9m, £916.1m, £683.9m, £689.1m, £635.8m, £749.8m, £608.6m, £703.2m, £655.1m, £744.5m, £623.4m, Leicester = £58.3m!, £585.3m, £753.1m.)

I used to call this basic figure the Title Zone; a mark that needed to be surpassed to win the league. Leicester dented that theory somewhat – although nothing is ever 100% set in concrete in sport – but the Title Zone has only been broken once in 14 years. Liverpool were frequently only halfway towards the Title Zone under Rafa Benítez, Brendan Rodgers and Jürgen Klopp.

But it’s getting closer. This season the Reds could be fielding a team that costs £500m+ after inflation; but the Manchester clubs will both be at £700m+, and maybe even more if they pull out some late big spending. (And if they don’t spend big, they still have all those mega signings in their squads. They don’t have to start with only their youth team this season, do they? Paul Pogba doesn’t becomes cheap because of the Rolls Royce Phantom logic.)

Liverpool are moving in the right direction, achieved by selling a key asset (Philippe Coutinho), reaching two European finals in the past three seasons, expanding Anfield, and generally being a well-run club now. The sale of Coutinho was seen by many as a travesty; a lack of ambition. But it was what it always is when an insane fee is offered: a chance to bring in two or three top-quality (but undervalued) players with the money. It won’t always work (see the sale of Luis Suarez), but the aforementioned apotheosis of transfer dealing – the 1987 rebuilding of an entire attacking team – was funded by the sale of Ian Rush to Juventus.

It’s worth reiterating how Liverpool are suddenly able to spend money lately – the fact that it has been raised by now being one of the best-run clubs in the world; by progressing on the pitch, and by Klopp improving players to the point where almost all are worth much more money (beyond the simple rise in inflation) than when they were signed.

A tweet attributed to Transfermarkt (or using their data) read: “Since Klopp has taken charge of #LFC the club’s squad value has increased by €557m. At the start of his reign, the squad was worth €356m and it’s now worth €915m. No other club has had a bigger increase in their overall transfer value.”

[Note: these values are nothing to do with our inflation model, but relate to increases in estimated market value; whereas our “current money fees” are essentially what was paid in, say, 2012 or 2017, converted to 2018 money. Obviously the estimated value of players also increases with inflation too – everyone’s value seems to rise when a new transfer record is set – but Mo Salah’s new valuation of £135m on Transfermarkt – which may still be on the light side – relates in part to the market doubling in value in the past year or so, in addition to his outrageous success, minus a small amount for being a year older.]

Obviously part of this increase in LFC’s squad value is from buying players like van Dijk, Alisson and Keita, for fees above £50m. But also, Liverpool have “lost” a £150m asset in 2018, and crucially, have added value to not only a ton of value in reasonable-prized signings like Salah, Roberto Firmino and Sadio Mané, but turned cheap players like Andrew Robertson and Joe Gomez into far more valuable assets.

The incredible success rate (to date) of Jürgen Klopp and Michael Edwards

Liverpool appear to know what they’re doing now, and much of it relates to the excellent relationship between Jürgen Klopp and Michael Edwards, ably assisted by Mike Gordon.

The excellent Melissa Reddy wrote a fine piece for Joe.co.uk the other day on the three ‘wise’ men, which I suggest you all read, to better understand how the club works.

However, as I said the other day, I don’t think the owners are suddenly changing tack: they put the money raised from transfers back into the team (if not immediately, then when players become available, with Klopp himself often preferring to wait for players than throw money at an inferior solution), and are raising revenues to raise the wage bill, without bowing to superstar culture and crazy demands.

I have defended FSG for this from the outset (if not always some of their decisions, but then judgement calls can always go either way), as it’s the way I think football clubs should be run; a belief predating even my knowledge of FSG, or NESV as they then were.

It just so happens that the wisdom of Liverpool’s transfer “committee” is now tied to an elite world-class manager who works with them, rather than against them. This is doubly beneficial because Klopp is not only a better, higher-profile manager than Brendan Rodgers, but Klopp is also less insecure (and therefore less likely to create egotistical squabbles). Rodgers will feel he had a right to work the way he did, but it was adversarial in terms of the whole transfer team and all that knowledge. By contrast, Klopp taps into that knowledge.

Liverpool are not suddenly trying to “buy the league”, as the money has been raised by progress on the pitch and selling an “unsellable” player. To not then spend that money if the right players can be identified would be perverse. In no way are the Reds just throwing money at it, as I will prove.

Liverpool are doing many of the same things as before, but doing them better because of a shared vision, and also, the increase in quality of performances and players under Klopp has a) raised more money from European adventures, and b) enabled the club to finally compete in the Champions League in a second consecutive season in FSG’s tenure, having finished in the top four at a time when there are six very strong contenders.

This – along with Klopp’s presence – creates a virtuous cycle, whereby it’s easier to attract better players as there’s the Champions League, better team-mates to play alongside, and the attraction of the giant gurning, grinning German, for whom top players want to play. Unlike Rodgers, Klopp – with is stellar reputation and incredible relatability – can talk to top players and suddenly they only want to play for Liverpool.

As before, the squad is not being filled with established world-class talent, a slew of older pros, egos and players on outsized wages – although part of the loss of direction in Rodgers’ final 15 months included buying a melting striker (Rickie Lambert) and the one-man-team-spirit-wrecking-ball that was Mario Balotelli.

FSG and Edwards are still targeting young players with the logical benefit of sell-on values, but perhaps now aged 22-25, rather than 20-22; although this is in part, I think, related to how, even in the last 10 years, life in the Premier League has got harder for 20- and- 21-year-olds, let alone kids even younger than that. There will always be exceptions, but the teenage prodigy has become rarer, and it seems that now most players are only of the sufficient physical and mental maturity at around the age of 22. The faster the Premier League gets, the stronger, and the more high-profile, the tougher it becomes for players at the far edges of the age spectrum.

(Liverpool’s 19-21-year-old signings have proved a mixed bag, as you might expect. Philippe Coutinho was an instant hit, while Jordan Henderson and Emre Can eventually thrived; but Divock Origi, Sebastian Coates, Luis Alberto, Fabio Borini and Lazar Markovic saw their careers stall – although time, and a change of scenery, can often help these players prove themselves later in their careers. Both Dominic Solanke and Marko Grujic are nicely placed to have good careers at Liverpool, but at this point it seems it could go either way for either of them.)

In the same period Liverpool have also obviously had flops in the 23-25 age bracket, as age itself won’t guarantee success. But this narrow band – just 24 months in the age bracket – includes Suarez, Sturridge, Firmino, Mané, Robertson, Wijnaldum, Oxlade-Chamberlain and Salah, and Alisson and Keita are the latest additions to it (van Dijk was 26 when signed).

Resale value is important because it enables you to do what Liverpool did with the sale of Coutinho: improve several positions, if done well. But Salah and van Dijk will see a dip in their transfer values in the next few years, as they get closer to 30; but if they continue to be as successful on the pitch, and want to stay at the club, the resale value becomes unimportant.

That said, when you don’t want is for your whole team to all hit their 30s at the same time, so that the entire team will start to melt, and little money can be recouped to rebuild the side. Of course, some clubs are still willing to pay what seem silly amounts for players as old as 33. But if Liverpool have a core of 4-5 players so successful that major honours are won in the next 3-4 years, then losing some transfer value will be offset by the rewards of success, and success allows for a steady reinvestment in fresh players in other positions. And again, if Liverpool have a core of 4-5 players so successful that major honours are won in the next 3-4 years, and then those players can move to Spain or Italy at the age of 29 or 30 for a reasonable fee, then that’s another win-win.

(The full list of older players – aged 27+ – who have been signed since 2010, albeit with four of them arriving before FSG took over, reads as: Meireles, Bogdan, Cole, Konchesky, Jovanovic, Milner, Poulsen, Klavan, Doni, Bellamy, Toure, Lambert and Manninger. Bar a couple of exceptions, that’s a big OUCH! Not a lot lost in transfer fees, admittedly, but that’s a ton of wage expenditure right there.)

Value For Money

Since Klopp arrived, the only clear non-successes (or yet-to-have-made-it-youngsters) have cost less £6m or less (or £11m if adjusting the pre-2017/18 signings for inflation).

These are Marko Grujic (bought for the future, maturing nicely without yet breaking through); Dominic Solanke (bought for the future, played well last season in general terms, and remains a top prospect, but failed to score headline-grabbing goals); Alex Manninger (very old 3rd-choice keeper on a free for a year); Loris Karius (poor first season, but much better second season until Kiev, but only 38% of league games started since arriving, and now consigned to no.2, at best); and on loan, Steven Caulker.

But if we were to base it on minutes played in relation to fee, Solanke would be a hit, and he would also be a hit – if not a runaway smash – in my judgement of his playing style, even if it’s still a little rough around the edges; it’s just that, subjectively, people don’t yet understand his value. So I won’t argue that he’s been a hit, yet.

You could also argue that Joel Matip, on a free, and Ragnar Klavan (£6,244,961 after inflation) are not exactly successes, but they’ve played a decent amount of football for almost no transfer fees (Matip featuring in 64.5% of league games, Klavan 40.8%), and both have had really good spells, as well as some ordinary ones. Again, minutes played in relation to fee would have both down as successful transfers, but it could be that they are Liverpool’s 3rd and 4th choice centre-backs this season, with Joe Gomez perhaps challenging for that role, too.

As of December 2017, approaching the mid-point of last season, you’d have said that Andy Robertson and Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain were also flops. Even though you should never be premature in doing so, if you had to judge them purely on their output up to that point, you’d have struggled to say they were proving successful buys.

Certainly they were not succeeding at that point, based on minutes played in relation to fee, where the more expensive Ox got more minutes but looked lost, and Robertson did pretty well but Alberto Moreno was in surprisingly good form, and so the new Scot rarely featured. But then between December the end of the season (or mid-April for Ox) that all changed, and both would go down as successes at this precise juncture, albeit with Oxlade-Chamberlain due to miss this coming season, and now having a long road to recovery to establish himself again (and to retain the perception of a successful purchase, rather than a good buy turned sour because his career was ravaged by injury; a bit like Kevin MacDonald in the mid-’80s).

Of course, with every successful new purchase made, a club increases the odds of someone else becoming a flop. Hitherto successful purchases can be edged out of the team as upgrades arrive, albeit a process that gets harder when the quality is already at a high level.

I’m a big Gini Wijnaldum fan, and think that he’s one of the best midfielders in Europe at what he does: holding onto the ball in tight spaces and finding a way to move the ball to team-mates close by, with neat passing and nifty footwork reminiscent of John Barnes in his later role in the midfield, and with a similar ability to shield the ball (but with less girth).

He should be scoring more goals, and creating more for others, even though his position has dropped from an attacking central midfielder to an even deeper role at times. Even ignoring the vital goals scored in big games (mostly in 2016/17, but one huge one in 2017/18), he’s clearly been a hit up to this point, and has featured in 80% of the Reds’ league games in his two years at the club; the 2nd-highest amount of any of Klopp’s signings who have been at the club for more than a few months. (Mo Salah leads the way at 90%.)

But will Wijnaldum become surplus to requirements? I hope not, and yet in a way, I hope he does, if it means the new midfielders are operating on a whole new level. Wijnaldum could still have a very important role to play, but my sense is that Fabinho will edge him out of the holding option, and that Keita could genuinely become the best attacking midfielder in the world – he really is that good.

On the subject of Keita, when someone like Daniel Sturridge is blown away by a new signing’s abilities – given who Sturridge has played with at Liverpool, including Suarez, Gerrard, Coutinho and Salah – you know it bodes well. Keita is not only a creative passer and thrilling dribbler, but he wins the ball back in the final third like an elite holding midfielder might; and, allied to the pressing of Bobby Firmino, could leave Klopp to have the best possible “creative” source of final-third regains.

When teams look to totally bypass the press of Firmino and Keita, they will hit the giant defensive diamond of van Dijk, Lovren (or Matip), Fabinho and Alisson, who can then get the ball quickly to Salah and Mané, and back to Keita and Firmino.

Evolution, Not Revolution

An adage for Liverpool since 2015 could be: “Don’t bring in too many first-team players in at once”. In each of Klopp’s three summers to date he and Michael Edwards have brought in four or five players each time. (Six with Alex Manninger, but not sure how much he counts, as his role seemed to be to tie the nets to the goalposts at Melwood.)

And, don’t throw them all in the team at once. Only Mo Salah started last season as a 1st-teamer, although van Dijk was an obvious addition too, in January – but which again proves the above adage of staggering their introductions.

Seven arrived in the summer of 2015, months before Klopp was involved with Liverpool, and 10 were signed in the summer of 2014. The summer before that it was eight (and in fairness, that was one hell of a season). But it seemed like more of a throw-mud-and-sees-what-sticks approach, which is what worked for Chelsea 15 years ago – you buck the trend of hits and flops by buying so many players that you get enough successes – but of course, they did so on a whole other scale, as I will later come onto.

Even in 2013/14, none of the new players, bar Simon Mignolet, were regulars that season, with the next-most-frequently-used player being Kolo Toure, with 20 Premier League games played, then Victor Moses (mostly as a sub) and Mamadou Sakho, who featured in just half of the league games. The core of that side were players at Liverpool when Brendan Rodgers arrived, or added by the committee in January 2013, when the Ulsterman’s poor judgement in transfers in 2012 had seen him lose his right to make the calls. (Without doubt, Rodgers’ coaching skills helped most of these players to improve, but it was short-lived, in part because he was given back more transfer power based on that thrilling season and the squad ended up as a jumbled mess.)

The downside to the approach is that it’s too much churn; too many new faces, no stability, no unity. You can try and address all your problems at once (if money is no object), but what happens? No one has any understanding with one another, and if the team struggles to find its harmony and rhythm in the early weeks the pressure ramps up, then the new signings who don’t hit the ground running can get almost railroaded out of the side. Potentially good buys can get lost as the season starts to fall apart.

If it takes a year for most players to learn the intricacies of a well-drilled pressing system, and if players (obviously) learn more about each others’ games through time and practice, then churn becomes a problem. If it takes time to properly bond with other people, and create an outstanding team spirit, then churn is a problem.

Everton, when “winning the transfer window”, signed SIXTEEN players in 2017/18! (No wonder Sam Allardyce didn’t trust them to try and pass to each other.) A couple of them were 20 years old, and maybe not meant for the first team, but that’s a staggering amount of churn. The only time I can remember so much churn actually working was also involving Ronald Koeman, when Liverpool and others raided his Southampton team, and the next season the new additions instantly settled and surprised everyone.

Having said all that, there’s one batch of signings from Premier League history – albeit in amongst a ton of churn, and several financial differences – that, surprisingly, reminds me of Liverpool’s work these past couple of years. The method – slow addition vs megabucks churn – is very different, but the key successes of that megabucks churn share some characteristics with Liverpool’s buying this past year.

Liverpool Are Replicating The Successes of Chelsea’s Buying of 2004-2005 (But Without the Insane Fees)

One thing for starters: Liverpool cannot ever hope match, with inflation taken into account, the insane amount of money paid by Chelsea in the mid-’00s.

The total spent by Chelsea – in NET terms – between 2003 and 2007, when adjusted for our Transfer Price Index inflation, is a mind-blowing £1.4bn.

Over the next two seasons (2007-2009) their inflation-adjusted net spend was just £15.3m – or just 1% of what they had been spending.

Of course, the main flaw with net spend (which is at least better than the terrible gross spend arguments) is that the difference between the cost of the team in 2008 and 2009 was not that different to 2005 or 2006, because they still had a lot of those players.

(Ditto with Jose Mourinho claiming his Man United can’t now compete this season. You still have all those expensive players, Jose! You still have Pogba, Lukaku, Mata, Valencia, Young, de Gea, Lindelöf, Fellaini, Jones, Sánchez, Martial, Shaw, Rojo, Bailly, Matic – they don’t all disappear because they were signed before this summer.)

The average cost of the Chelsea side between 2003 and 2007 (the average of the line-ups over 38 league games) was £826m in 2018 money, and between 2007 and 2009 it was £732.2m, a drop of “just” 11% – in contrast to 100x less net spend. (Hence, net spend is a shit argument, but again, better than gross spend. Gross spend is a terrible argument as it never takes into account what you have lost.)

But what Chelsea got right, in amongst the chaos of dozens and dozens of transfers and some hefty fees – before vanity signings like Andriy Shevchenko started pitching up – was the signing of certain types of player: young, hungry, fit, strong and often from far-flung places, like Africa (via Europe). Indeed, I can find four super-successful Chelsea signings in that period that match closely to what Liverpool have done in the transfer market in the past year (without wasting hundreds of millions on dozens of flops in the process).

Didier Drogba and Michael Essien were emerging talents, bought not from elite European super-clubs but from the French market. Drogba, an African goalscorer, was 25 at the time; just like Mo Salah last summer. Essien, from Ghana, was 22 at the time, the same age Keita was when the deal with Liverpool was struck (he’s 23 now).

Then there’s Petr Cech, bought in 2003 for what now adjusts to £67,733,471, aged 21. Again, an outstanding piece of business, for a fee almost identical (after adding the essential factor of inflation) to the one Liverpool have just paid for Alisson.

Cech would have be classed as better value in one sense, as he was four years younger than Liverpool’s new keeper, meaning he could potentially play longer than Alisson will; and we’ll all be happy if Alisson has just a few years like Cech at his best.

(While keepers can go on to their late-30s, their best years for save percentage average out at 28-30, although the elite ones should still be producing the goods at 33, but perhaps not 37 anymore. Cech himself is a good example of how keepers’ reactions can start to look much slower with age. Most, with just one or two exceptions, look washed up by their mid-30s now.)

Finally, the commanding and assured mid-20s centre-back: Ricardo Carvalho, costing a whopping £146,105,116 in 2018 money. By contrast van Dijk looks a bargain. Indeed, Rio Ferdinand was also far more expensive as a centre-back, costing Leeds United £125,837,529, and Man United £197,930,506 (the third costliest transfer in the database), albeit with the player a big success at both clubs, first in terms of profit for Leeds, then longevity and trophies for United.

Eliaquim Mangala’s fee when joining Man City is now an eye-watering £106,443,648. With inflation, van Dijk ranks as the 11th most expensive Premier League defender, and isn’t even Liverpool’s costliest; that honour goes to Glen Johnson.

(Although why is so much being made of Liverpool breaking the world records for defenders and goalkeepers, when these amounts are a mere third of what the actual world record is? Why do these two positions have to have their own records? It’s all just money, just as City paying £50m for full-backs last season was somehow allowed to become a big deal, thanks to Mourinho’s moaning, when Mourinho had just spent £75m-£90m on a single player, having done the same in 2016?)

Indeed, in terms of all players signed by Premier League clubs, Virgil van Dijk ranks way down at 99th – before the addition of this summer’s transfers – in the list of most expensive signed since 1992; and Alisson at 131st, costing Liverpool, in relative terms, the same as what was paid for El Hadji Diouf in 2002.

As I do every year, here’s the list of the most expensive players after inflation, in current day money, before I move onto the concluding part of the article.

Conclusion

As noted before, the market can also drop. This window feels hard to judge right now. First, there’s the obvious big-money signings, but it’s easy (before going through all the deals, one by one) to miss the high number of cheap signings who fall under the radar, and lower the average.

Then there’s the World Cup, which delayed some transfers, and the new transfer deadline (thankfully) brought forward to the eve of the new season, which means a lot may be crammed into the coming two-and-a-half weeks. Some clubs may hold out to the last minute to get a better deal, but I like how Klopp tries to get all his signings in as early as possible, to know what he has to work with, and indeed, to start working with them. Saving £2m by delaying the deal to deadline day can seem a bit of a false economy.

Anyway, to go back to that excellent Chelsea side that won back-to-back titles (but lost back-to-back semi-finals against Liverpool), it was a young team that Jose Mourinho began working with in 2004; winning the league aged 25.2, which is in the 95th percentile for a Premier League-era team, and the youngest champions in the Premier League era until Manchester City last season, at 25.1. (Liverpool’s side last season averaged out at just 24.3.)

While following the latest trend is often fraught with problems, I wonder if Mourinho’s time in the game has made him less trustful of younger players, the older he himself gets, and the more distrustful he just seems in general. He seems to be buying – and being linked with – a lot of older players, to add to a fairly (but not remarkably) young side that will be a year older anyway.

I guess the beauty of the Premier League, and football in general, is that different approaches can lead to success. And right now I wouldn’t write any of the top six off from finishing in the top four (although two will have to fail).

But for the first time in years it feels like Liverpool can be one of maybe only three or four clubs that can win the title, if the Reds’ new players settle quickly (or at least start delivering before the winter), and Klopp’s men get a fair dose of the necessary luck required on the way to a title.

Given that only three years ago we were all praying just to be able to make the top four, and less than eight years ago were praying that our team could get out of the relegation zone (and avoid going into administration), it’s been a significant improvement.

This is a young side that perhaps has three years to try and land #19. But the beauty of Jürgen Klopp’s sides is that there’s rarely a dull moment, and the ride is often a joy in itself. Winning is important, but excitement and long-lasting memories aren’t to be sniffed at.

For the season ahead I will again try to make as much of TTT’s content paywalled, with the occasional freebie, as we rely on subscriptions to exist. Our latest book, Boom!, is also, we hope, worth adding to your Amazon basket.