First of all let me say that, right now, this feels like Schrödinger’s Final. Such has been the wait – it will be two weeks without a game – that I haven’t allowed myself to contemplate the outcome for more than the most fleeting of moments, before I force myself to think of something else. Just like AC Milan’s players touching the trophy as they walked out onto the pitch in Istanbul, I don’t think it’s healthy to visualise winning; you have to believe it possible, of course, but it’s dangerous to then go too far ahead in your mind.

Indeed, while visualisation techniques can be helpful in picturing how you will, for example, take a penalty kick, imagining larger-scale success – bigger-picture successes, long into the future – has been shown to lessen the desire for that success (i.e. your brain already feels partially sated). I think it’s why managers are always telling their players to take it one game at a time.

And of course, the safest mental approach as fans is always to hope for the best and prepare for the worst; not to feel a sense of impending doom – don’t try to beat disaster to the punch, as Brené Brown puts it, and suck the joy out of the situation –but instead be open to the possibility that things don’t always go how we hope, and so much is beyond our control (and even beyond the control of the team’s manager and his players; see the way James Milner was essentially punished in the home leg against Roma for having a rocket-shot hit straight at him. You can’t control everything).

Having said all that, if you’re going to Kyiv – and quite a few TTT subscribers appear to be going to the final, along with our editor, Chris Rowland – I think it’s only right to be buzzing about the travel, the camaraderie, and just the whole experience. That’s something that you have more control over than how your team actually plays.

I knew this trip was beyond my current health limits, but I obviously had the time of my life in Istanbul; and even Athens in 2007 I remember fondly, for the craic in Greece with friends and for a pretty good performance in an unlucky defeat (albeit one I have never watched back on video). However, I am trying not to even think of Liverpool winning a 6th European title. I believe it can be achieved, but one mistake, one refereeing error or one missed penalty can undo any good work – and that’s football. Also, the payoff – to win that 6th – would be incredible, and therefore to not achieve it would hurt like hell. But of course, to be at the sharp end of things always comes with the risk of pain, in the way that being mid-table or out early never does. That’s not painful, but numbing.

Therefore, Liverpool are simultaneously Champions of Europe and the losers in Kyiv. The club is existing in two states at one time, for what feels like weeks on end, depending on whether I briefly let my guard down and allow myself to dream (which causes flutters in the stomach) or contemplate life as the defeated underdogs (which is gutting, but without shame), before I override these thoughts and start thinking of, say, the brightest objects in the solar system after the sun and Roberto Firmino’s teeth (no.3 = Jürgen Klopp’s teeth).

Is Liverpool’s youthful vigour going to take control, or will Madrid “nous” their way to another win, I have found myself thinking, before trying to drown out the buzz in my brain and the butterflies in my belly by bingeing on a Netflix documentary series (in this case, one about a slightly simple man forced to rob a bank with a ticking bomb strapped to his neck, which I obviously took to be a fake. I mean, who does that, right? Footage was then shown from police dash-cams and local news crews of said bomb exploding around said man’s head, and, shocked and shaken at having seen his blurry death, I ponder if wondering about Kyiv might not be so bad after all. But by then I’m hooked into the craziest of crime stories and another day has passed without fixating on Schrödinger’s Final.)

In a way, of course, we should be enjoying the prospect of a third Champions League final in just fourteen often difficult years; even in the halcyon years of 1964-1990 – over two and a half decades – the club only reached five, albeit for a variety of reasons (not least the post-Heysel ban, and the fact that you never qualified unless you won the league or were defending the trophy; plus, the group stages provide a little more insurance these days).

It is indeed a remarkable achievement, just to be there. While I remain curious as to which players arrive next season and who will leave, it seems almost pointless to speculate and think too far ahead. They won’t be in Kyiv, will they? For now, Kyiv is all that matters. Again, the assistant-managerial position is interesting; but Kyiv comes first.

And winning the Champions League would be better than any possible transfer activity. Yes, the club has to try and improve again next season, no matter what, but when Schrödinger’s Final finally arrives, it needs to savoured. After all, even though it’s the club’s third in 14 years, it’s these kind of relatively rare occasions (alas, also the club’s third in 33 years) that we feverishly demand the club buy 2,379 expensive players to get to.

Hearts and Minds

I think it’s also worth noting that even if Liverpool fail to win on Saturday, this team will be remembered for all the right reasons. Manchester United may have finished 2nd in the league, but they have captured no one’s imagination. Liverpool are in a genuine race for the title of Champions of Europe; one game away, having scored the most goals and kept the most clean sheets. By contrast, Man United were never in a league title race. They have so many expensive and incredibly talented players (who win them games), but lack heart and cohesion. They epitomise “fear football”, almost exclusively unable to take games to the opposition (albeit the one time they did was in beating Liverpool 2-1, but hung on by somehow getting away with the referee not awarding three clear penalties; Marcus Rashford’s reward for being superb that day appears to be being benched and slated by his manager. Again, this is fear football; not trusting younger players because of the mistakes they might make, opposed to the brilliance they can bring.) They only usually start playing when behind, which is when it gets easier.

They spent a fortune to dog-out narrow wins since October, and to lose badly on the biggest of stages. They bought Alexis Sanchez, it seems, because they were afraid of Man City getting him; and give him £500,000-a-week to be on the periphery of games. Again, fear.

Contrast Jose Mourinho’s Man United with Newcastle in the mid-’90s (who also cost a lot of money), and how people mock Kevin Keegan for failing to win the league; but they are remembered, and not just for blowing the title. The Holland side of the 1970s are the most famous example of teams winning nothing but hearts and minds.

To win has to be the ultimate objective, but in an age where money gives the richest teams the edge, and the trophies are clustered around the three richest clubs in each country (or in some cases, the only rich club in a country, like in France and Scotland, and less so, Germany), there’s a need to thrill fans. Klopp’s football, with Dortmund and Liverpool, will be talked about in 50 years’ time.

Kings

In recent history, and very, very ancient history, Real Madrid are the the Kings of Europe (or el rey de Europa, as Google translate tells me). But between 1967 and 2013 Liverpool actually won the European Cup/Champions League almost twice as often as Real Madrid. All the insane talents (managers and players) and the obscene spending – the Galácticos – landed them the biggest trophy of all just three times in that period, in amongst their 12 overall. They are currently the masters of big-game football, albeit still fallible. And right now, given the age of the team, they are past their peak, but still capable of finding ways to win.

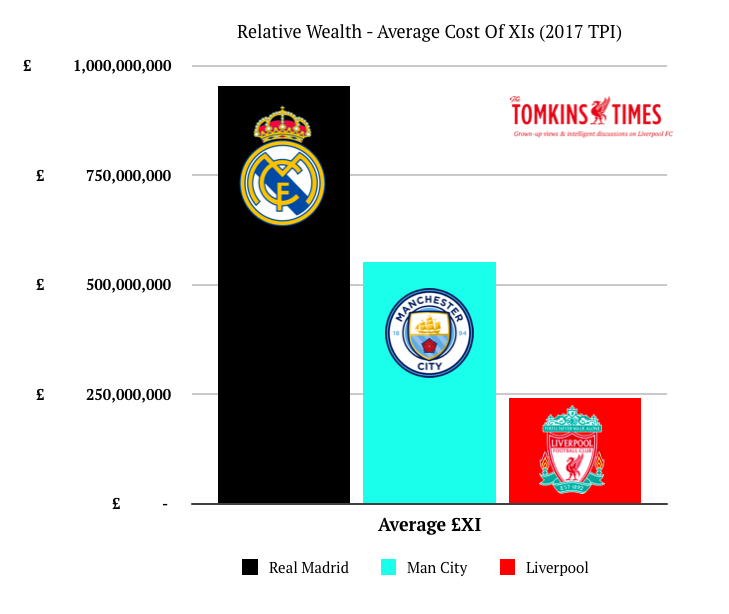

They play in ice-cold white, to Liverpool’s red heat. Almost to a man they are old; Liverpool are young. Mostly they are slow (or slowing down); mostly Liverpool are fast. They are experienced trophy-collectors; Liverpool are on the hunt for a rare one these days. The are not short of egotistical superstars; Liverpool are humble hard-workers. They are perhaps the most expensive team in the history of world football; by contrast, Liverpool’s 2017/18 side ranks a lowly 51st in terms of £XI (cost of all 38 XIs adjusted for football inflation) in the Premier League since 1992. This is not one of England’s historically expensive sides; this is not Chelsea between 2004 and 2015, or Man United from 1999 onwards. Liverpool have one expensive player.

Indeed, while I will go on to explain the financial gulf later in the piece (behind the paywall), I will leave this graph directly below, to show the comparative chasm. The difference is roughly the same as that between Liverpool and Stoke City; and it’s credit to Klopp that the Reds go to the final as underdogs, but underdogs with a more than decent chance of winning. (Note: Liverpool and Manchester City’s figures are £XIs, the average inflated cost of all 38 league selections in 2017 money, while Madrid’s figure – as we don’t track the Spanish league – is the inflated cost of the eleven, with Premier League inflation applied – which is fairly accurate given most of their spending went to Man United and Spurs – likely to start in the final.)

No Country For Old Men

Hopefully Kyiv will prove no country for old men (bar James Milner). Cristiano Ronaldo is 33, Sergio Ramos 32, Luka Modric 32, Keylor Navas 31, Karim Benzema 30, Marcelo 30; while Toni Kroos is 28, as is Nacho. Gareth Bale turns 29 this summer. Two of those players broke the world record for transfer fee; for fees that, with our Transfer Price Index inflation, now rank over £200m; indeed, Ronaldo is getting up towards £300m.

Aside from Marco Asensio, 22, and Mateo Kovačić, 24, their younger regulars are Raphaël Varane, 25, Casemiro, 26, Lucas Vázquez, 26, Dani Carvajal, 26, and even Isco – who seems to be permanently defined as a youngster – is now 26.

The average age of Liverpool this season is just 24.2, making them the youngest Premier League team.

The majority of this article – which includes previewing the final and looking more deeply into Klopp’s hugely impressive European record over the past six years – is for subscribers only. See below for how to sign up and enjoy all the subscriber-only content and discussion.

[ttt-subscribe-article]