By Tim James

The archetypal English football team is that of a deep defensive line and continuous long balls to a big man up-front. Like many football trends, this has been modernised. Leicester utilised many of the same principles on their way to a historic Premier League victory, but with an increased focus on intelligent pressing and counter attacking over long balls. Many other teams also try to implement this style of play.

Despite strong results against the Premier League’s top teams, Liverpool have found these deeper defences harder to break down. Lower-table teams have long been an issue for the club (one special season aside), and this is partly because Liverpool’s focus has generally been away from attacking organisation.

Similarly, the key strength of Jurgen Klopp’s teams has never been their organisation in attack. At Mainz, Dortmund and now Liverpool, the German has implemented a style of play based on an aggressive counterpress and rapid transitions. Both the Premier League and Bundesliga are famed for their rapid pace, but there is one key difference: Bundesliga teams consistently press more aggressively than their lower-table Premier League counterparts. Only Darmstadt consistently implement a style of play that allows the opposition large amounts of possession.

As Liverpool manager, Klopp has been confronted with a number of opposition teams happy to cede possession and sit deep. One such team was Burnley, and again Liverpool struggled to create dangerous chances despite a huge amount of possession (80.6%). The line-up was stacked full of attacking personnel, but the Burnley defence held strong for a 2-0 victory.

So how do you break down a low block? There were immediate calls for the return of a big striker up front, mere hours after the departure of Christian Benteke. But there are many other ways to open up a low block without totally altering the team’s style of play. If the team spends much time training in a particular way, completing altering the style and strategy seems counterproductive. Instead, a similar style to the team’s norm can be utilised with a few tweaks to the implementation.

Fluidity: it is a positive?

Liverpool have clearly exhibited the ability to operate with large amounts of fluidity in the final third. Particularly within Klopp’s 4-3-2-1, the outer central midfielders can often be found as the furthest players forward with forwards dropping deep to fill the vacant space. Many of the players do not have a true position, instead floating into space organically as play develops.

This fluidity has clear advantages against a certain style of deep defensive line. When the opposition elect to utilise man-marking (or a derivative of man-marking), this fluidity can totally disrupt the shape of the opposition. Man-marking suggests the opposition will closely follow their opponent, and so positional rotations such as this can drag players away from their original position.

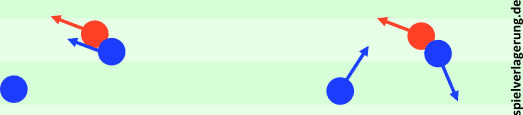

A rough illustration of the difference between man-marking and man-marking within a zone. Of course, it is more of a continuum than a strict categorisation. There are infinite potential combinations.

Utilising positional rotations against a man-marking team forces them into constant decision making. Do they switch the man they mark after a rotation is completed, or do they follow them and stick to a strict man-marking system? Both have major disadvantages: switching can be difficult to communicate and co-ordinate effectively over 90 minutes, but not switching necessitates a huge physical effort to stick with the direct opponent. It is an inherently reactive strategy and involves mirroring the opponent, who has the advantage of making his decision in advance: a sharp movement in any direction can create enough separation to receive the ball.

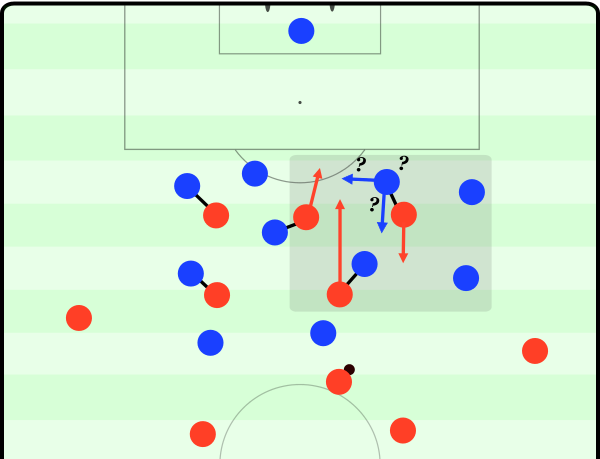

A simple example of how positional rotation can disrupt man-marking: when the striker drops to receive the ball to feet, does the central defender follow him? What happens to the onrushing midfielders? Many questions to answer in little time.

Man-marking is a common strategy within the Premier League, and Liverpool will likely find success against these teams because of this fluidity. The only team to use a similar scheme that Liverpool struggled against last season were Manchester United, who favoured man-orientations during Louis van Gaal’s tenure. It is worth mentioning that this was far from a low block, instead focusing on aggressive pressing. On the other hand, Burnley’s approach was more zonal-based, with defenders only pressing aggressively when the Liverpool ball-player moves into their area. Because of this, the midfield rotations are less disruptive to their defensive shape.

The squad is also composed largely of physical players, who are comfortable outmuscling their direct opponent in broken play and chaotic 1 v 1 situations. More of these types of situations arise within a man-marking defensive scheme, which benefits Klopp’s team. Those who are not physically strong (such as Mane, Lallana & Coutinho) are adept at using their agility and dribbling skills in these 1 v 1 moments. Even these less physical players have a natural aggression which creates a proclivity for winning individual duels.

Poor offensive spacing causing defensive instability

Positional rotations are hard to successfully implement consistently. When they don’t work, it can lead to players in the same zone and other spacing issues. One such example that has been a common theme throughout Klopp’s time at Liverpool is the midfielders pushing into the forward line, and then not being replaced by a forward dropping deep. This is particularly the case in the 4-3-2-1, where the outer central midfielders are given license to push forward.

Immediately prior to the counter leading to Burnley’s second goal: Liverpool have many players in advanced areas, but too many players on the same horizontal area of the pitch.

Having many players on the same line of the pitch means there are fewer passing options for the ball-player. When the pass is made into one of the players in an advanced area, he is likely to lose the ball unless he immediately passes straight back to the previous player because he cannot access many of his teammates with a pass. In this case, Sturridge loses possession before he can make the pass back. Whilst he was criticised for his role in the counter-attack (as was Lallana for his loss of possession against Arsenal), Liverpool’s structure was more to blame for the ease at which Burnley attacked after the loss in possession.

When there are too many players on the same horizontal line of the pitch, it also makes the team less stable defensively. It gives poor access to the ball and makes the counterpress (or ‘gegenpress’) more one-dimensional. This is particularly the case when too many players are ahead of the ball, as the opposition can merely move in the opposite direction. If players are staggered and well-spaced across the pitch, then not only will they have more immediate passing options, but the counterpress will also exert more pressure. When at their best, Liverpool aggressively counterpress from all directions, which makes it difficult for the opposition to consistently make good decisions.

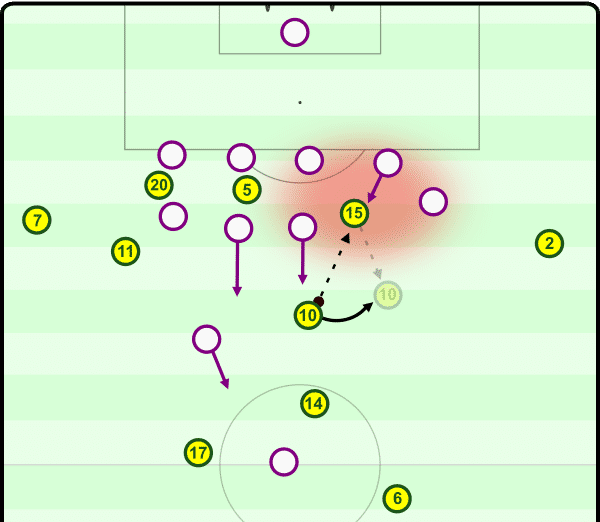

Another key reason Liverpool seem undermanned in defensive transition is the positioning of players on the far-side. If the ball is on the left of the pitch, it is less important for the team’s right-back to be in a very advanced position. Firstly, being in such a high position makes it difficult to circulate the ball to him successfully, and therefore the opposition do not need to adjust their defense because of his presence. Moreno has this issue in build-up, but both Milner & Clyne exhibited this trait during attacking organisation against Burnley.

If there is a nearby midfielder, then the effect is magnified – operating in the same passing lane as that midfielder means the full-back is not providing any additional disruption to the opposition block.

The advanced positioning of the far-side full-back also reduces his potential impact in defensive transition. Depending on the opposition, this means the central defenders and deep midfield have larger spaces to cover, which can be very difficult for any player.

How can Liverpool improve against a zonal low block?

The rest of this article is for subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]