By Mihail Vladimirov.

Summary:

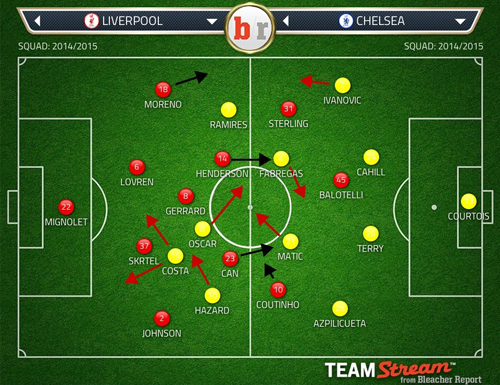

- Liverpool lined up, once again, in a 4-1-2-3 for a big match; Chelsea set up in their usual 4-2-1-3.

- Chelsea started with a broken 5 x 5 out of possession, trying to press Liverpool’s deep recycling, at the same time as preventing any counter attacking threat by retreating deeper with their five defensive players.

- Because of the Blues’ lack of intensity in the press, the Reds managed to easily manoeuvre around it and create some dangerous moments, including the opening goal.

- Henderson man marked Fabregas, frustrating the Spanish playmaker but at the same time, robbing Liverpool of a vital attacking cog.

- Can also tried to get tight to Matic at times, leaving Gerrard very exposed in between the lines.

- Chelsea targeted Liverpool’s left side, often overloading with Oscar and even Hazard on occasion. They also had plenty of cover with Ramires and Ivanovic.

- Once Chelsea started to press efficiently, Liverpool collapsed; often misplacing passes, and inviting more attacking pressure from Mourinho’s team.

- Rodgers failed to respond to these issues, and the home team continued to struggle until half-time.

- Chelsea in the driving seat after their second goal.

- Liverpool lacked a specific plan of how to score a goal.

- The substitution of Coutinho and leaving Lallana on the bench was baffling.

- Rodgers’ in-game management was passive and questionable.

Introduction

There was much debate about Rodgers’ team selection for the Real Madrid game and the fact that he lined-up with a heavily rotated starting XI. Despite him hinting it wasn’t the usual first-team players being rested, but more like dropped after a poor run of form, there was a suspicion he was always going to use them all from the start in the Chelsea game.

And so it proved: Lovren, Johnson, Gerrard, Henderson, Coutinho, Sterling and Balotelli were reinstated to the starting XI, with Emre Can the only change to the line-up from the previous league game against Newcastle (Allen was also benched). Once again, Rodgers went for the 4-1-2-3 formation in a big game. But instead of it looking like the 4-3-2-1 used against Man City earlier in the season and then in both Real Madrid matches, here the shape was more like a lopsided 4-diamond-2 with Coutinho deeper and narrower on the right flank with Sterling staying higher and wider on the left side.

For Chelsea, Mourinho didn’t make any surprising changes in formation or personnel. Expectedly, Azpilicueta was recalled to the starting XI following his suspension while Ramires was preferred on the right flank to Willian (arguably to offer greater midfield solidity and defensive abilities to cover for Fabregas’ usual roaming movement). The rest of the team was as usual in what was Chelsea’s default 4-2-1-3 formation.

Liverpool proactive in possession, Chelsea out of it

Unsurprisingly, Liverpool started dominating the game by bossing possession and attacking in a direct manner as soon as they succeeded carrying the ball forward out of their third. However, instead of retreating to their usual 4-4-1-1 (which is actually more like 2×4+2) defensive shape, focused on compressing the space through the middle and pushing the opposition out wide, Chelsea actually also opted for more proactive behaviour when out of possession.

First, the pre-game expectations that Mourinho might look to man-mark Gerrard and Sterling didn’t play out that way in reality. Neither player was specifically tightly marked beyond the inherent marking, following the fact both teams were perfectly matched due to their mirroring formations – Liverpool’s 4-1-2-3 and Chelsea’s 4-2-1-3.

Chelsea’s proactivity when out of possession was immediately clear as soon as the game started and Liverpool begun to, as usual, methodically look to play out from the back. In such instances, Chelsea’s front four – keenly helped by Fabregas – looked to quickly push forward and occupy the opposition’s deep-lying recyclers (the back four and Gerrard). It wasn’t a case of the visitors applying a fast-paced, high-intensive pressing though – it was more of a half-hearted attempt to simply stay closer to the opposition’s players and prevent them receiving the ball easily with the aim to try and slow down the passing process or just force it to go long.

The problem for Chelsea though was that such behaviour from their front five badly exposed the backline while not really putting any real pressure on preventing Liverpool quickly and purposefully playing out from the back. The lack of real effort to quickly and aggressively close down meant Chelsea’s ‘pressers’ were easily bypassed by Liverpool’s deep passing moves and the ball was successfully played into the midfield zone. The real problem though was that once the front five unit was so easily taken out of the game, now there were huge gaps opening up in the middle third. This effect was further magnified by the fact that although the front five players looked to push on and occupy Liverpool from higher up, the back four remained in relatively deep positions, leaving Matic to cover the ocean of space left throughout the whole midfield area on his own.

It’s not uncommon for a Mourinho team to look in such a ‘broken’ 5×5 way when trying to press the opposition. This was largely the strategy he used in his Real Madrid days in the games against Barcelona. The theory is that you use the front five to press from higher up, while the back four remain deeper and prevent simple balls over the top or down the channels to catch you on the break, leaving one player to patrol the midfield zone and stay on whomever of the opposition’s midfielders manages to break away off the ball. The aim simply is to simultaneously ruin the opposition’s passing flow right from its start and origin from the back, while not being vulnerable to counter-attacks, more so if your centre-backs are not the most mobile ones.

Tactically, such a strategy makes sense against teams who are dependent on a potent passing flow, continually building their attacks from the back, but in the meantime are short of counter-attacking outlets as their centre-forward usually drops deep to participate in the build-up play (so the onus is on the midfielders and wide men to provide the off-ball threat and get in behind). Which is why you leave your back four in relatively deep positions as to not be easily caught out of position with someone running past them and getting in behind. This Liverpool XI was suitable for such a strategy to be deployed as Balotelli and Coutinho usually drop deep and join the build-up play with only Sterling and Henderson looking capable to threaten in behind (but only if there is space to do so). Therefore, Chelsea’s decision to use such a ‘broken’ press seemed sensible and suitable. The problem was the execution.

The rest of this analysis is for Subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]