Usually the preserve of subscribers only, this week’s tactical analysis – from Kais – is free to read by all.

Liverpool’s resurgence under Kenny Dalglish appeared to have been derailed by last week’s loss to West Ham, but the Reds emerged triumphant in this fixture, prevailing over a Manchester United team that has now lost three out of five Premier League games for the first time since 2004.

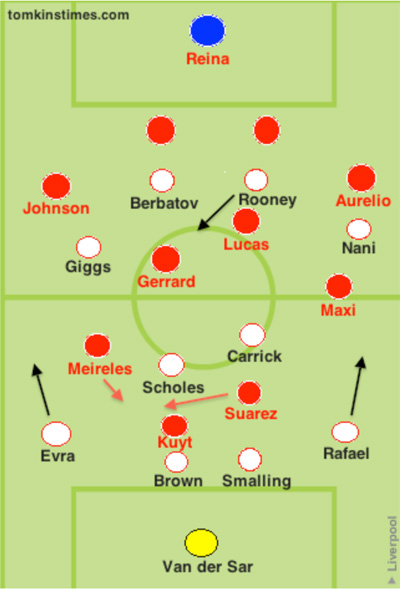

Tactical Line-ups

Having employed three centre-backs against West Ham last week, Dalglish and Clarke reverted to a more conventional back four here, as Liverpool were configured in a 4-2-3-1/4-4-1-1 shape: Glen Johnson started in his preferred right-back position in place of the injured Martin Kelly, and the returning Fabio Aurelio fulfilled the left-back role; Carragher partnered Skrtel in the centre of defence, with Daniel Agger still indisposed. Unfortunately, Aurelio’s reappearance in the starting line-up was brief, and his injury-enforced substitution saw Carragher shuffle out to right-back, as Kyrgiakos took his place at centre-back, while Johnson resumed service at left-back.

Lucas and Gerrard reprised their double pivot function, offering protection in front of the back four from their deep-lying midfield positions – although Gerrard would periodically make forward incursions to augment the home side’s attacking contingent, leaving the Brazilian as the sole defensive midfielder. Meireles and Maxi played on the right- and left-hand flanks respectively, while the scintillating Suarez supported lone-striker Kuyt from a deeper position, as he sought to find space between Manchester United’s defensive and midfield lines.

Alex Ferguson’s decision to utilise a standard 4-4-2 was somewhat surprising, given his previous inclination towards a 4-5-1/4-3-3 in the ostensibly ‘big’ games, as he did against Marseille in the Champions League recently (perhaps an admission that he no longer considers Liverpool a legitimate rival?) – although it must be noted that he used a 4-4-2 against Liverpool in the FA Cup this season, and against Chelsea last week as well.

Brown, who replaced the suspended Vidic, partnered Smalling in the centre of defence, with Evra and Rafael fielded in their usual full-back roles. The selections in midfield were perhaps the most intriguing: Fletcher was consigned to the bench, as Scholes and Carrick formed the central midfield two – which implied that the away team had no genuine holding midfielder in the line-up. Giggs played on the left wing and (budding thespian) Nani was on the right. Up-front, Berbatov was selected in place of Hernandez to play alongside Rooney – presumably in the hope that he would repeat his superb hat-trick performance against the Merseysiders earlier this season.

Key Tactical Points

The contest began in predictably aggressive fashion, with each side seeking to press the other high up the pitch, in order to disrupt the opponent’s attempts to maintain possession or construct moves from the back. Both United strikers sought to close down Skrtel or Carragher when either received the ball from a short goal-kick from Reina; Kuyt was similarly diligent in pressing the United centre-backs when they were in possession close to their own goal.

A significant tactical distinction was the teams’ contrasting deployment of the wide-midfielders: Nani and Giggs were instructed to stay wide on the touchline, in order to stretch the Liverpool defence and, by virtue of forcing the Liverpool fullbacks to track them out wide, could manufacture space in the centre for Berbatov and Rooney to capitalise on; in sharp contrast, Liverpool’s two wide-men, Meireles and Maxi – neither of whom are genuine wingers – opted to drift inside, staying narrow in order to interact with Kuyt and Suarez, while also attempting to create room for either Aurelio or Johnson to maraud forward and offer width.

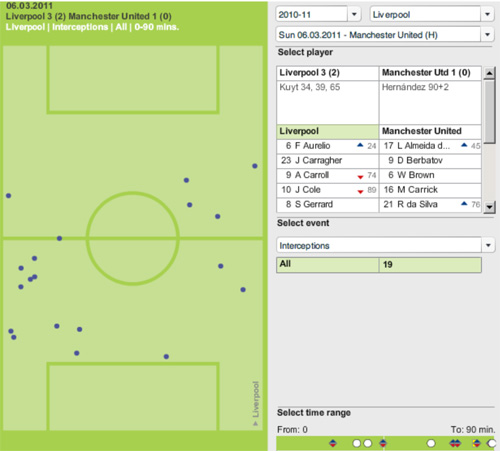

Liverpool’s interceptions chalkboard demonstrates perfectly United’s intention to constantly use the wide areas in order to breach the home team’s backline:

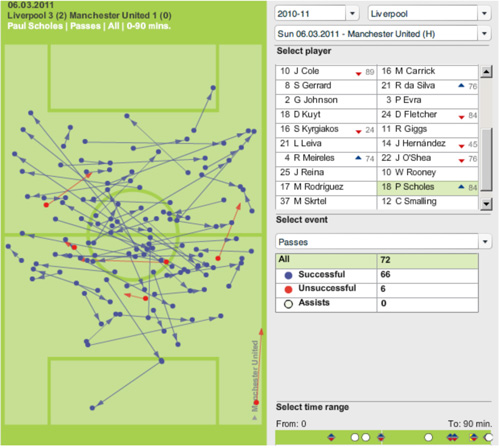

The two divergent strategies necessitated a different passing style by each team’s central midfield unit as well; Scholes and Carrick’s principal remit was to remain in deeper areas and play lateral passes to each other, before releasing more expansive, diagonal balls to either Nani or Giggs on the wing, constantly switching the orientation of attack in order to drag the Liverpool defence from one flank to another in order to facilitate a crossing or shooting opportunity.

Scholes’ impressive passing chalkboard illustrates this approach perfectly:

Lucas and Gerrard, on the other hand, tended to play forward passes to Meireles and Maxi, who were stationed in narrower positions – the intention was to engender chances by moving up the pitch using the now familiar ‘pass-and-move’ schema of Dalglish’s Liverpool.

As a result, during the initial stages at least, the home team found it easier to keep possession (the possession statistics were 61%-39% for the first 10 minutes) and infiltrate United’s defensive areas, as there were always shorter passing options available in the centre of the park, given the predilection of both wide-men to come inside and advance the circulation of the ball up the pitch in that manner.

Further, Suarez’s propensity to drop into deeper positions to collect the ball meant that Liverpool often benefited from overmanning the central areas and inside channels of the pitch. The interchange between the Reds’ most ‘attack-minded’ three – Kuyt, Suarez and Meireles – lent variety and unpredictability to the Liverpool team in attack; there were times when Kuyt and Suarez would drift into deeper areas, leaving Meireles as the most advanced player – which left the United centre-backs with no one to mark and generally unwilling to distort their defensive structure and leave space behind them by pursuing the Liverpool forwards into those sectors of the pitch (although Smalling did push out on occasion).

Suarez often drifted out to the right, in order to exploit the space vacated on that flank by Evra’s surges forward; in fact, 61% of Liverpool’s attacking play came down that side in the first 20 minutes. The home team’s passing chalkboard for the entire game also reveals a general bias toward attacking down that flank (Maxi’s 4th minute chance and Kuyt’s 2nd goal, for example, originated from that side of the pitch); the intention was presumably to target the rusty Wes Brown, who played as the centre-back on that side and was frequently left susceptible to LFC’s attacking incursions when Evra was stranded upfield:

The same fluidity was conspicuously absent in the away team, with their structure being more ‘rigid’ in terms of positioning – reinforcing Steve Clarke’s observations earlier in the week that this particular iteration are more “functional” and do not possess the level of “flair” that Machester United teams of the past did.

The intention of deploying Scholes and Carrick in withdrawn midfield positions was to enable them to make unrestrained passes from less congested areas, which would presumably lure Gerrard and Lucas up the pitch to confront them; this, in turn, would unlatch the two holding midfielders from their position in front of the LFC defence and create pockets of space for Berbatov or Rooney to benefit from if they decided to waft into the resulting corridor between LFC’s defensive and midfield lines.

However, Suarez’s willingness to track back and pick up up the deepest-lying United midfielder (usually Scholes) until the United man crossed the half-way line – after which he would be ‘passed on’ for either Lucas or Gerrard to contend with – allowed the home team to maintain the security of the double pivot in front of the back four and constrict the space for Rooney and Berbatov to operate in, whenever they attempted to evade the centre-backs by dropping off into Hitzfeld’s Red Zone.

While Gerrard has been justifiably criticised for his tactical ineptitude and lack of posititional awareness when playing this position in the past, he remained more circumspect in this match, working in tandem with Meireles and Johnson (later Carragher) to curb the threat emanating from United’s left flank; he dropped in at right-back, for instance, to cover for Johnson’s upfield jaunts in the first half; he helped to ‘double up’ on Rooney when the United man attacked from the left wing in the 2nd half; and he restricted his attacking excursions, in order to assist Lucas in executing their deep-lying defensive brief.

Consequently, while United were later able to dominate possession – although this was primarily in the 2nd half, when Liverpool had a two-goal lead and were content to retreat and preserve their advantage – they generally seemed to lack penetration in attack, despite Berbatov’s astute lateral movement.

Nani’s unfortunate injury from Carragher’s terrible challenge, and his subsequent substitution late in the first half by Hernandez required Rooney to go out to the left wing, while Giggs switched to the right. United were now playing with ‘inverted’ wingers on both flanks; each player was naturally disposed to cut in with the ball, rather than going on the outside. While this allowed United to maintain possession better in the 2nd half, as there were now passing outlets for Scholes and Carrick in narrower, closer positions, United were unable to permeate Liverpool’s defence, which had now withdrawn closer to goal in order to counter the veritable threat posed by Hernandez’s pace.

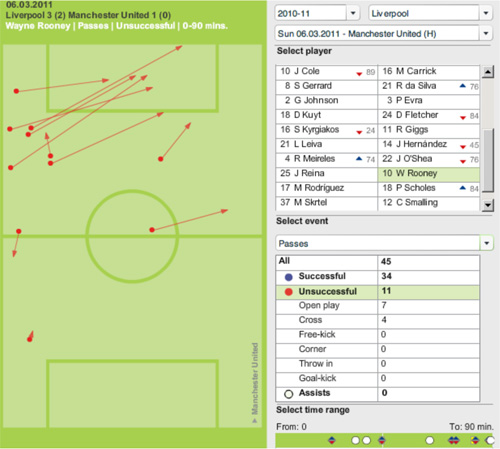

Johnson was able to comfortably subdue Giggs’ attempt to come inside, as it was onto the Liverpool defender’s stronger right foot; and even though Rooney was able to elude Carragher’s marking on the other flank, his crossing to the far post was quite woeful and often overhit – a symptom of United’s overall impotence in attack – as this passing chalkboard illustrates:

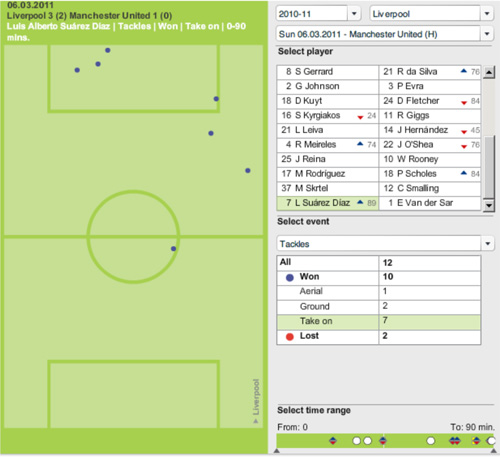

The ineffectual Rooney and Berbatov were eclipsed by Liverpool’s two protagonists: Kuyt and Suarez. Kuyt’s intuitive movement off-the-ball allowed him to link up play effectively for Liverpool, while his positional prescience yielded the close-range finishes for his first hat-trick as a Liverpool player. Suarez’s coruscating brilliance on-the-ball – epitomised by the exquisite turn that led to the first goal, which was vaguely reminiscent of Torres’ goal against Marseille in 2007 – provided a dimension in attack that Liverpool have been lacking for quite some time: a direct, pacy threat. His affinity for ‘taking-on’ a defender is aptly substantiated by the following chalkboard:

That Suarez was frequently liberated to pick up the ball in space is perhaps an indictment of Fergie’s perplexing and rather cavalier decision not to include a defensive midfielder (although, to be fair, Fletcher was apparently ill), or to sacrifice one forward and employ a third central midfielder to pack the midfield, as he has done previously in matches of this magnitude. The Scholes-Carrick partnership, for all its assuredness in possession, lacked vigor and proved incapable of resisting Liverpool’s surges in the centre of the park.

This was, ultimately, an unequivocal tactical victory for Dalglish and Clarke – one distinguished by Suarez’s effervescence and Kuyt’s plundering of Van Der Sar’s goal, as well as the reassuring introduction of Andy Carroll, who might well forge a useful partnership with the Uruguayan.