How much value is removed from a squad each season in terms of personnel who, due to age or contracts running down, are lost to a club?

Whether or not players are bought and sold for profit, there will always be the inevitable wastage. I got onto this train of thought when someone said, with relation to Benítez’s net spend since 2007, “£10m a year is not enough to sustain a top side”.

Although he only cost £2.6m in 1999 (£6.2m in today’s money, according to TPI©), Hyypia’s value in his prime was way beyond that in terms of influence. Even at the age of 36, when he understandably left for regular first team football in a slower-paced league, that value hit home: he needed replacing.

And you don’t find players with a) that much quality, and b) that much ‘cohesion’ with the club ethos, the manager’s ideas and his team-mates just like that … if at all.

And you don’t find players with a) that much quality, and b) that much ‘cohesion’ with the club ethos, the manager’s ideas and his team-mates just like that … if at all.

Every manager gets a good proportion of his purchases wrong. And every manager strikes gold now and again. In Gérard Houllier’s case, it was a more a case of ‘worth his weight in diamonds’ when he signed Hyypia from Willem II; beyond doubt his masterstroke, and well done to Ron Yeats for spotting him.

As I’ve noted before, some of the best of his own signings bequeathed to Benítez – Hyypia, Hamann, Finnan, Kewell, Smicer, Babbel, Dudek – were all the wrong side of that late-20s barrier, or virtually useless due to illness or injuries (or in Dudek’s case, a lack of confidence and consistency, which, for a goalkeeper, are essential).

These were not players that could be relied upon long-term.

Many of the rest – Biscan, Cheyrou, Diao, Diouf, Le Tallec, Baros, Cissé, Traore, Vignal, Partridge, Medjani, Kirkland, Welsh, Otsemobor, Mellor and Pongolle – were all young, just not really good enough. Meanwhile, Owen and Heskey were already as good as sold.

So it didn’t leave a lot to work with: Riise, Gerrard and Carragher were about the only three who could potentially last beyond a handful of years, and only two of those were indisputably good enough. Given the way the finances have changed, Benítez has had to completely overhaul the squad – and not just replace, but improve it – with less money, relatively speaking, than his predecessor.

Clearly a lot of money was needed to turn those who weren’t good enough – and there were loads – and those who were getting old, into a side that could compete beyond the next couple of years.

Now, Benítez didn’t really have a lot of money – not in net terms – but he still made the Reds perennial Champions League threats, and registered two +82pts seasons. It’s clear that David Moores had little money when compared with his rivals, and it’s clear that Gillett and Hicks have not pumped money into the club.

Before getting onto his recent transfer activity, it’s clear that Benítez couldn’t raise billions from the sale of the duds he inherited.

Contract complications meant that about £10m was wiped off Owen’s value (2004 prices), and Babbel, Smicer, Dudek, Diao, Kewell, Hamann and Biscan were all released for nothing before too long.

How much did Liverpool lose in the way these players’ values diminished? Well, football inflation peaked between 2004 and 2008, meaning that buying the equivalent player from Houllier’s time could cost twice as much.

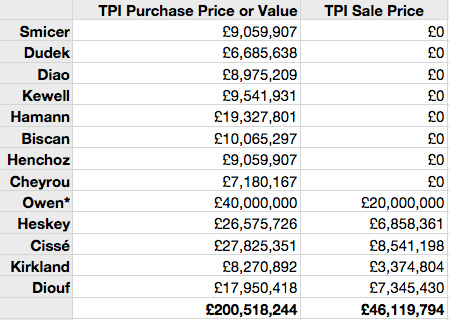

Using TPI, in today’s prices, the following six players cost Liverpool £63m to buy: Smicer (£9,059,907), Dudek (£6,685,638), Diao (£8,975,209), Kewell (£9,541,931), Hamann (£19,327,801), Cheyrou (£7,180,167) and Biscan (£10,065,297).

(A year ago, these values would have been even higher; in the past 12 months, the average price of a player has actually dropped; all in all, today’s prices still fairly closely reflect those between 2005 and 2007, when a lot of these players were released.)

What’s fascinating is how much Pepe Reina actually cost: almost identical to the original fee paid for Dudek, when TPI is applied. But Dudek left for free.

Even more striking is how Javier Mascherano, the ‘Didi Hamann’ of defensive midfielders in 2010, cost roughly the same as the German’s TPI value. But Hamann left for free.

(Applying TPI to Reina and Mascherano brings us out at £10m and £22m respectively; still excellent value for money, clearly, and an indication that, in 2010 prices, it’s hard to get much below £10m.)

But it gets worse; far worse.

In today’s money, Emile Heskey cost Liverpool £26,575,726. Cissé cost £27,825,351. Diouf cost £17,950,418. And in today’s money, Liverpool lost half of Owen’s £40m value, assuming that he was worth £20m in 2004.

Look at the above chart. Twelve players who, in today’s money, had cost £160m (plus one who was worth £40) brought in just £46m when leaving Liverpool.

(Note: in addition, small profits were made on Baros, Traore and one or two others; but small losses were made on Murphy, Sinama-Pongolle and Le Tallec.)

So when, during the first few years of Benítez’s reign, players needed replacing, the squad the Spaniard inherited had lost a lot of its worth.

This is not meant to be unduly harsh on Houllier; he had made some shrewd purchases in his time, and as I continually say, a 50% record of successes in the transfer market is pretty good going for most top managers.

But by the time he left, it was mostly ageing stars with a limited shelf-life and piles of deadwood.

Now, of course, Benítez also bought some of his own flops with the money he was given, which included the limited sums recouped from those necessary sales. However, he also clearly improved the squad. Nunez and Josemi flopped; Alonso and Garcia led the club to glory. A year later, Reina and Crouch added new dimensions, but Zenden and Morientes failed to deliver.

By my rule of thumb, if a good judge in the transfer market has to buy ten players, only five are likely to be successful; and maybe only one or two sensational. Some will be squad players who don’t get a look in because someone else is doing better; some will fail to settle; some will get seriously injured; some will fail to deal with expectations/pressure at a big club; and some will just turn out to be not as good as the scouting reports suggested.

But all the while, every year, no matter how well a manager is doing, valuable assets are falling off the end of the line. Picture it like a conveyor belt, with each passing year pushing everyone – good and bad – closer to the waste bin.

So, Hyypia left for nothing; his replacement, Kyrgiakos, arrived for £1.5m. (A true replacement would probably have cost £10m+.)

But when Hamann left for nothing, his replacement cost £18m. There’s not a lot of difference between Hyypia (past his best) and Kyrgiakos (as he is now), and not a lot of difference between Hamann and Mascherano, but they cost Benítez a fair chunk of his net spend.

Solution?

Unless you can afford to keep bringing in ready-made stars for the going rate, the only solutions are to buy your own free players, or to bring through the youth.

So far, Benítez has signed Pellegrino, Zenden, Fowler, Voronin, Degen and Maxi on free transfers. Of these, only Maxi looks to be a steal, while Fowler at least enjoyed an excellent half a season after his return. But scouring the market for free transfers is tough, as you can see; most managers would do well to get more than the occasional one spot-on.

This summer, the Reds had the chance to sign £15m-rated Marouane Chamakh on a Bosman – the first time since Markus Babbel that a free transfer would involve someone of great repute arriving, and/or wasn’t seen to be past his best.

But despite the player and his agent saying that Liverpool were his preferred destination, the negotiations were badly handled, much to Benítez’s despair. At least Milan Jovanovic, another player in fairly high demand, seems set to sign, although even that doesn’t appear to be 100% watertight just yet.

But these are the kind of free transfers the Reds must be looking out for, if funds are tight. (The Ballack-type Bosmans, when the player also nets £120,000 a week, are out of Liverpool’s price range.)

The alternative is to ‘grow’ your own stars, or pick up, for negligible fees, the top players of tomorrow. This, of course, is easier said than done. (And when Benítez wanted to do so with Aaron Ramsey and Theo Walcott, Rick Parry said that they were no better than what was already at the Academy.)

It was not until 2009 – five years after his appointment – that Benítez had a really strong say over the failing Academy. His act was to bring in Rodolfo Borrell – the man responsible for much of Barcelona’s incredible youth success in this area.

Youth Shambles

Borrell was not impressed with what he encountered. “The reality of what we found here was unacceptable,” recently Borrell told BBC Sport, in what was a damning indictment of years of failure.

Steve Heighway seems a decent man, and oversaw the successful rise to prominence of several Liverpool stars in the 1990s. But, to me at least, he seemed blinded to the fact that no local talents were coming through the ranks. Had he lost touch with what was going on elsewhere?

Three years ago he said Jay Spearing was ready for the Liverpool first XI. Last night, Spearing was a sub in a Championship play-off match on loan at Leicester City; he’s had some (unremarkable) games at Liverpool, but the idea that he was ready for the Reds’ first team three years ago seems utterly ludicrous. He’s a decent, honest player; no more, no less.

And yet Spearing is one of the best local players to come through the ranks; all the while, Heighway’s statement put pressure on Benítez to pick players who were patently not good enough.

The problem appeared to be that Benítez wanted the youth system overhauled, but Heighway was a firm ally of Rick Parry, and that pair kept him at bay; Parry’s son just happened to work with Heighway. In 2007 Parry appointed Piet Hamberg as the Academy’s Technical Director, and things appeared to get no better.

Clearly all Benítez wanted was players good enough to be regulars in the first XI, rather than barely touch the fringes; no manager ever wants otherwise.

Since then, the U18s have been revamped, with new additions to the squad; as opposed to the headlines of Youth Cup runs, their league campaign has produced some sensational stuff.

The initial signs are very promising – the U18s look an exciting side, and the U16s thrashed Man United 6-0 – but it could take years for it to bear fruit. That’s the problem with youth development – it takes a hell of a lot of time, and requires masses of patience. And as far as Benítez is concerned, it’s possibly all too late to save his ill-gotten reputation.

(As I also noted recently, rather than rely on almost 100 part-time, amateur local scouts, some of whom were in their 80s, Benítez has whittled it down to a dozen-or-so professionals; the aim that no more mistakes occur to rank with Liverpool fan Jack Rodwell not being scouted.)

Mistakes have been made by Benítez and his overseas scouts, too; too many average foreign kids have arrived, although crucially, most have been no worse than the English.

Martin Kelly, Nathan Eccleston, Stephen Darby and Jack Robinson have all featured in league games this season, although only Kelly appears to be truly ready as things stand.

Insua and Ngog, both teenagers when signed, have had tough seasons, but have shown promise – not just naivety. Nemeth has experienced some senior football on loan in Greece. And Hungarian keeper Peter Gulacsi has made the bench, and believe me, he’s a real prospect (even if Pepe Reina will never be shifted).

Then there’s the Spaniards Pacheco and Ayala, who appear to show that, when it comes to sourcing his homeland for talent, Rafa has the right scouts in place.

Benítez has handled Pacheco well, bearing in mind the fans’ clamour to see him more regularly, despite the chasm in quality between the reserves and the first team. Both of these 19-year-olds have been blooded in meaningful fixtures, and that’s the key.

Now, three or four of these players can happily take their place in the Reds’ 24-man squad for next season; two or three might make the 18. Jonjo Shelvey, signed from Charlton, is another who may have the potential to push straight into the 18, although it’s too early to be certain.

But beyond 15 or 16 players, that 24 has looked too weak, and beyond one or two really bad buys on the manager’s part, this has been a result of breaking even to pay off debt, rather than strengthen; gone is the yearly investment to replace those like Hyypia with similar talents.

Unlike Houllier, Benítez has made profits on a lot of his own transfers, and usually, at the very worst, a player will not lose all value (Pennant is the only one I can think of).

What Next?

Albert Riera will raise a few million, as will some of the others who may be surplus to requirements, such as Ryan Babel. And as with Voronin, the fee procured by selling Degen will at least cover his wages while at the club.

But where does the money for five or six new players come from? Selling six or seven might bring in enough cash to buy three or four, and even with a bit of luck (law of averages, etc), only two or three might be successes.

This is where riches are at their most telling: no matter how many poor signings Man City made last season, and will make this summer, they will get enough right to improve the squad, while the rest – £19m Jo, £32m Robinho, £18m Santa Cruz – are shrugged off. C’est la vie.

The most damning financial statement is that Liverpool are currently paying £110,000 A DAY in interest on bank loans used not to improve the club, but simply for a leveraged buyout.

That is roughly the weekly wage of a world-class player (a top-class one, at least) every single day. That means that every single week, Liverpool could be paying David Villa, David Silva and five others, rather than interest on loans that have done nothing to improve the club.

Of course, not that there’s the transfer kitty to sign such talents.

Liverpool’s current squad costs approximately £143m. The club’s debt is more than twice (arguably three times) that amount. Whatever Benítez’s mistakes, the overriding fact is that he’s trying to build a bastion on quicksand, with two Yanks having made off with his foundations.