Just when I think I’ve got little new to say about Rafa Benítez and his work at Liverpool, his record comes under attack yet again, and I feel compelled to put that record straight. While Benítez can no longer even be referred to as Liverpool’s previous manager, ‘his’ players have been very much in the news this week. Again.

The latest nonsense came on BBC, following an interesting and open interview with the Spaniard. Martin Keown, sat in the Football Focus studio, said that he spent £230m on 77 players, and therefore would need money wherever he went. And so on continues the idea that Benítez was a reckless spender and a big-money waster.

Along with Graeme Riley and Gary Fulcher, I’d already covered Rafa’s record in Pay As You Play, in comparison with a number of the other major Premier League-era managers. Obviously issues can be covered in more depth in a book than on a blog, but I’ll try to point out a few truths.

First of all, the total of ‘77 players’ makes no sense.

I make it 43, because I’m not counting all the random youth players that all other managers buy for nominal fees but don’t get pulled up on. Perhaps Benítez bought too many of these, but as with the book, I’ve not taken them into account in terms of spending or recouping money. I’ve only looked at those who started a league game for the Reds.

Now, this is not done to favour Benítez; it was a rule of the book, and given the £5m recently received for San Jose, Dalle Valle, Kacaniklic and Palsson, and the £5m value of Daniel Pacheco (who’s yet to start a league match), it’s fair to say that, on the whole, he probably made more money than he lost in such deals. But the amounts aren’t massive either way.

Now, the point of Pay As You Play was to take all fees at 2010 money, whether a player was bought in 1993 or 2009. But for the sake of this piece, I will use both standard prices, and our Transfer Price Index’s CTPP (Current Transfer Purchase Price). With the 2010/11 transfer window now closed, we can calculate ‘2011 money’, but that’ll take a while to compile the data. So for now, all fees from last season are still at 2010 money. Capisce?

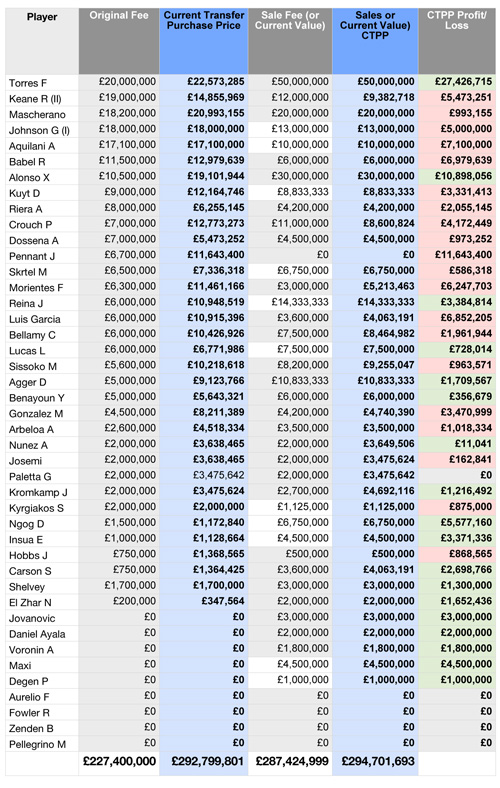

In actual money (i.e. discounting inflation), Benítez spent roughly £229m on players. So the £230m quoted on the BBC sofa is fairly accurate.

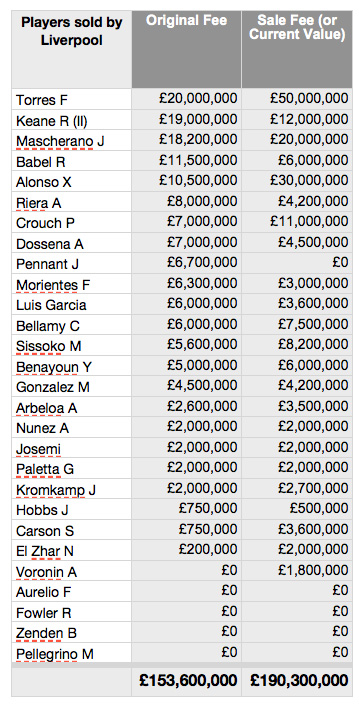

Of the 29 Benítez signings to have subsequently been sold by Liverpool, the figures are startling: £153.6m spent on those players by the Spaniard, and £190.3m recouped by himself and his two successors.

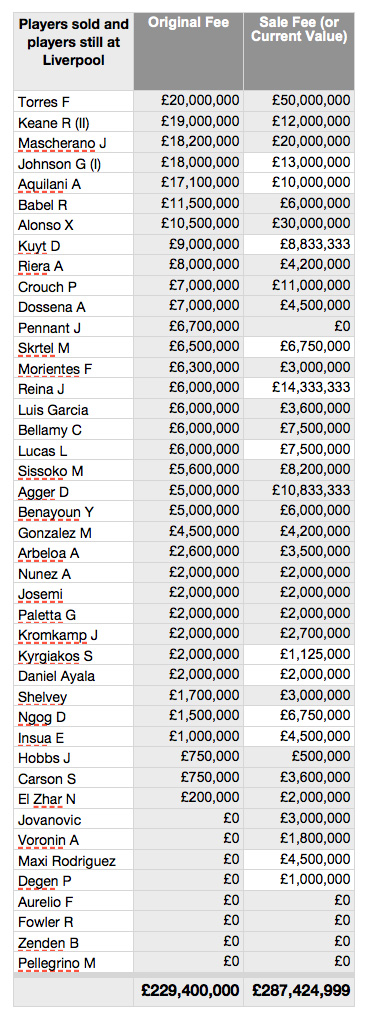

Add the other 14 signings still at the club, and it comes to £229.4m spent, but £287.4m in money recouped. In other words, if the rest of Rafa’s signings were sold off this season, he’d end up roughly £60m in profit, without inflation taken into account.

Now, current values of existing players were set by a panel of experts (football journalists, scouts) for the book. So these are speculation. What’s interesting is that Mascherano was valued at £20.1m, Torres at £48.8m and Babel at £7.8m, or £76.7m combined; the actual sale fees ended up at £76m. So while player value depends solely on what two clubs agree is acceptable, and change depending on the player’s form and fitness, our estimates of market value were fairly accurate.

One figure I would take umbrage at is the £14.3m valuation of Pepe Reina; word was that Arsenal bid in excess of £20m in the summer, so if anything, he (like many keepers) was undervalued, and one of Rafa’s best purchases is worth even more than listed. However, in other cases, players may be viewed as overvalued. But again, on the whole there is no way the figures are skewed in Benítez’s favour.

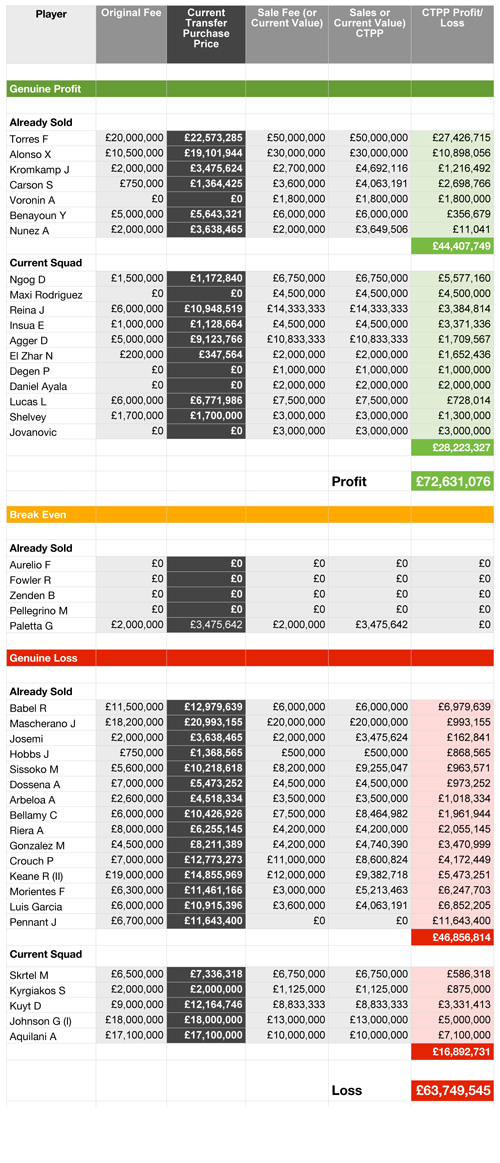

Genuine Profit

One of the concepts devised for Pay As You Play was ‘genuine profit’. In other words, it takes into account the value at the time of purchase when inflation is applied. A clear example is Xabi Alonso: £10.5m in 2004, but that equates to £19.1m in 2010 money. So with the sale for £30m, the ‘actual’ profit was closer to £10m rather than £20m.

This means that as, on average, prices rise more than they fall, it’s harder to make a genuine profit.

The following shows that, even under this harsher ‘rule’, Benítez comes out favourably. And the same is true by comparison with his contemporaries, with only Arsene Wenger outperforming him (and by a a small amount). Of the top points-scoring managers in the Premier League history, they were the only two who operated at a genuine profit.

The table below splits his signings into genuine profit – already sold and still at the club (i.e. rise in value) – break-even, and genuine loss.

Of course, in time this could all change; Glen Johnson’s value will depreciate as he nears 30 (though he’s still only 26), Alberto Aquilani may not yet be sold to Juventus if the Italian club can’t afford the pre-agreed fee, and so on; then again, players’ values can rise as well as fall, and a youngster like Jonjo Shelvey could be a £10m+ player of tomorrow. But when every last one of his signings has moved on, the club will almost certainly have earned more money in terms of transfer fees than it shelled out. Yes, there are wages to take into consideration, where even free transfers resulted in a ‘cost’; but there’s also prize money, which, following four extended Champions League runs, was at high levels between 2004 and 2009.

(As with all transfer work, the caveats are listed in the book – although many can be read here, in the Introduction.)

The Benítez chapter from Pay As You Play is available below for subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]