So, how does the job that Jürgen Klopp is doing compare with other new arrivals?

(Also, for a great piece on the Reds’ title chances, Mark Cohen’s TTT tour de force is now a totally free read.)

Since the start of last season no fewer than four major names have been appointed as manager within the upper echelons of the Premier League; joining the once über-successful Arsène Wenger, and the talented and hotly touted Mauricio Pochettino (but who has yet to win a trophy, and has yet to even break the 50% win barrier in any of his three jobs, albeit at 49% currently with Spurs [Edit: obviously since drafting this piece he has ruined this paragraph and is now bang on 50%]).

Pochettino continues to do a good job in north London, having taken his side to the Champions League (before being limply eliminated), and mounted a reasonable title-tilt last season in a field that opened up as the big guns went through turmoil; Spurs finishing with a pretty decent but unremarkable 70 points.

And Wenger continues to keep Arsenal on a really even, steady keel, performing well year after year without ever taking the step that he used to manage when Arsenal were relatively big spenders (or at least had an expensive £XI) up until 2004. The cost of Arsenal’s £XI is creeping up again, but no clear progress is being made.

Comparing and contrasting the six managers – but mainly the four new ones – is difficult given that each inherited a different situation and each has spent differing amounts of money to remedy problems. For instance, there’s no doubt that Antonio Conte is doing a “great” job, in that results are unprecedented thus far – but he inherited a team of title-winners who were fed up with the previous boss, rather than some perennial mid-table side.

Therefore, the greatness of the job he’s doing is clouded by what kind of team you want to say he inherited and therefore the level of progress made. All you can say is that gaining points at a rate that is getting up towards 100 (on a pro rata basis) is about as good as anyone can do. The bigger question is whether this is down to a freakish 12-game hot-streak based on surprising teams with a ‘new’ formation, or actually indicative of sustainable high-end quality. You’d expect them to slow down a bit, but the extent of that cooling off is what will be fascinating.

Conte, like Klopp last season and Pep Guardiola this, has had to come to terms with the aerial bombardments and constant quest for the second-ball. A few weeks ago Guardiola observed: “Here you have to control the second balls. Without that you cannot survive. At Leicester they took a throw-in and the second ball was a goal. In many other countries, when one guy has the ball at his feet, the people know what is going to happen. The football is more unpredictable here because the ball is in the air more than on the floor.” (I’ll be looking at Guardiola later in the piece, ahead of his first visit to Anfield as a manager.)

Conte has had less trouble adapting, but he inherited a team that, one bad season aside, was replete with aerial and second-ball nous. They weren’t trying to alter the way they played too much, while City, in contrast, have looked a bit more confused in the transition: lots of silky footballers, but fairly lightweight without the brute forces of Toure and Kompany for much of the campaign (and the pair possibly melting too; Toure certainly is, and Kompany is just never fit).

Chelsea have three diminutive regulars in Hazard, Pedro and Kante, and a modest-sized defender in Azpilicueta at 5’10”. Victor Moses is also 5’10”, but Marcos Alonso is a 6’2” wing-back, and Nemanja Matic, at 6’4”, is taller than most centre-backs. And unlike Arsenal, Liverpool and Manchester City, they have a brutish, battering-ram as a centre-forward.

(Arsenal also have Olivier Giroud, but he appears to have become a perennial sub, and while tall, isn’t necessarily aggressive. Liverpool also have Divock Origi, but while also big, he’s not really a physical forward – yet. While some players will never be particularly aggressive, knowing how to use your body effectively – as a shield – comes with experience. And most players only start to bulk-up in their early-20s. Usually the best young strikers are those who run in behind defences; target-men usually come of age much later, in the way that, like the art of defending, it’s heavily reliant on canniness.)

Chelsea have sufficient height, strength and power to deal with the rougher side of the game; although it needed a switch to 3-5-2 to set them on a 12-game winning streak; up to which point doubts were being expressed about the Italian boss, with chastening defeats to Liverpool and Arsenal. Since then things have been turned around very impressively.

But right now I wouldn’t swap Jürgen Klopp for anyone in the world. You can argue that better managers may exist (although Klopp’s skill-set is shared across a coaching trio; he’s not a lone wolf), but fit is such a crucial part of management. He has Liverpool punching above their weight more than anyone else in the top six.

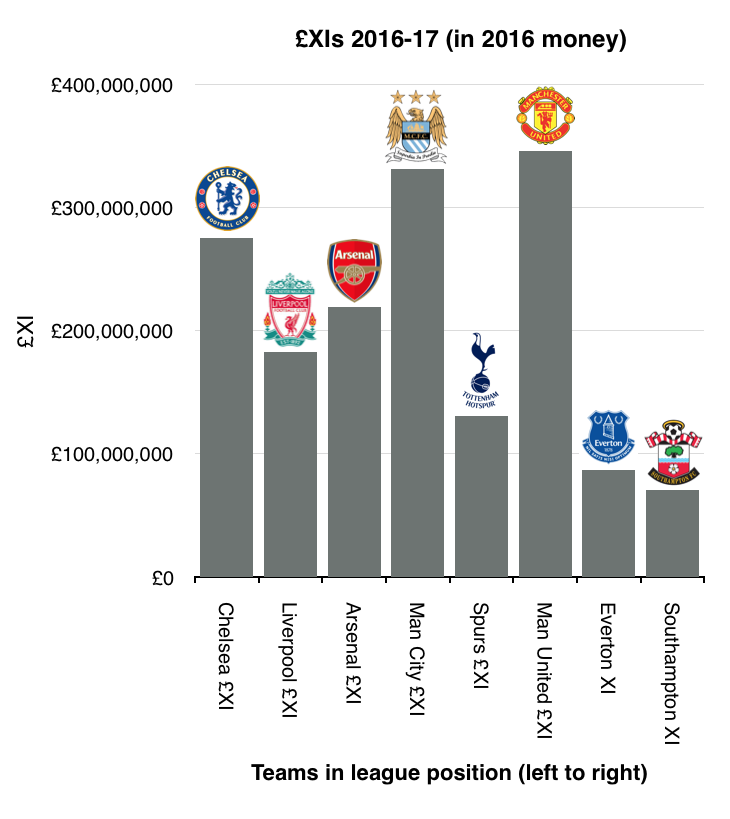

Although Leicester temporarily – but spectacularly – torpedoed what I used to call the Title Zone (teams needing to have an £XI of a certain amount to win the title ever since 2004), the current top six are the top six ranking sides for £XI (with “£XI” being the average cost of the starting XI with transfer fees adjusted for the Transfer Price Index inflation model I co-created with Graeme Riley, based on analysing every Premier League transfer).

Even more incredibly, Everton rank 7th and sit 7th, and Southampton rank 8th and sit 8th, with both a reasonable distance ahead of West Ham who rank 9th on spending (but 11th in the table).

So the eight “richest” teams (in £XI terms) occupy the top eight positions at what is just one game before the halfway stage, albeit with the top six – clearly with more financial power – pulling away from the chasing pack.

However, the order of the top six is never set in stone by spending; other factors come into play, as it always does – money only accounts for so much, with tactics, unity, fitness and myriad other issues at play in all areas of the league (but the gulf in finances means the richest usually rise towards the top).

The rule is usually that if you have a lot of money and spend it fairly well, and invest in a good manager (who hasn’t alienated the squad), you won’t be far away.

Last year was such an outlier as all the big clubs had major issues, and yet now are racking up points at an amazing rate. In 2014 Liverpool lost the title partly due to a record-breaking goalscoring of the winners (103 scored, that Liverpool almost matched but fell just short of with 101), whereas this year Chelsea are on course for a record points haul. (People talk about Liverpool’s defence costing the club in 2013/14, and maybe it did, but just two more goals – in the game against Chelsea, or before that at Palace – could have altered so much.)

Liverpool now, as in 2013/14 and 2008/09, may be better than a fair few recent title winners and yet destined to end up empty-handed due in part to timing. (Aka Sod’s Law.) I certainly hope that won’t be the case, but ultimately Liverpool can only do their best and see where it gets them.

Liverpool are now some way behind Arsenal with the 5th-highest ranking £XI – the first time Arsenal have really pulled away from Liverpool since before the Emirates was built (having fallen behind during the past decade), with an £XI that’s now £37m greater – but Arsenal themselves are a fair way adrift of Chelsea, while the two Manchester clubs are miles ahead of the rest.

Arsenal narrowly overtook Liverpool to rank as the 4th-highest £XI in 2014-15, but neither Wenger nor Klopp believe in big spending; Wenger possibly more of a spendthrift, and Klopp possibly more wary of big egos and anyone upsetting his complete desire for unity.

Klopp has the advantage of some extra time on the three big-name summer 2016 appointments, although Mourinho has spent much longer in the league; even though he was still moving clubs (which can lead to an obvious transition), and arriving at a giant labouring under the pressure of being in a genuine rut, he still had three years with Chelsea to assess the opposition and the various tactical approaches, in addition to an earlier three years at the club. Unlike what Klopp faced last season and Guardiola this, there shouldn’t have been anything to really surprise Mourinho this season, aside from yet again trailing Wenger, after years of getting the better of him. The longer that goes on, the more his “specialist in failure” jibe will come back to haunt him.

And yet, even though next month will mark Klopp’s third transfer window, he essentially did nothing in his first one; meaning that in 2015/16 he signed no one to improve what was a mixed-bag of a squad (which produced a mixed-bag of a season), bar Joel Matip and Marko Grujic for the summer, as well as taking Steven Caulker on a brief loan. The German had to mix a crazy schedule with assessing his players, assessing the opposition and making sense of the broad spectrum of approaches faced, and even then, was never going to try and solve all his problems with the chequebook.

So Klopp and Mourinho inherited very different situations: it’s fair to say that Mourinho would have extensively scouted Manchester United and their players since arriving back in England in 2013, and known more about his new squad than Klopp probably knew about Liverpool’s a month into his time on Merseyside. The Portuguese knew the players to be wary of in opposition ranks, and the players to go after (although his four buys were all imports).

He also immediately brought in a world-class star on a freebie, albeit on £300,000-a-week; and in fairness, Zlatan Ibrahimovic has surprised me with how well he’s done given his age and the physical nature of the league (but a little bit more on him later).

Paul Pogba’s fee broke the English record, albeit only ranking 5th since 1992 when adjusted for inflation.

Indeed, Mourinho has now signed four of the six most expensive players in the Premier League era after inflation (three for Chelsea and one for United), and now has access to a fifth – Wayne Rooney – albeit with the striker on the wane, no pun intended.

(Mourinho has yet another buy in the top 10: Shaun Wright-Phillips; so in 2016 money, he has effectively bought five of the ten most costly players of the past 25 years during just six years in England; and Ricardo Carvalho makes it six of the top 13, with Liverpool’s most expensive, Andy Carroll, only ranking 21st. Mourinho may argue against being a chequebook manager but the facts since Porto don’t seem to back that up.)

Also snapped up by United this summer was one of the best midfielders in Europe, Henrikh Mkhitaryan. Eric Bailly completed a quartet of signings, with almost no money recouped, meaning a big net spend – although it’s not Mourinho’s fault if United’s deadwood was not appealing to potential suitors to recoup large amounts. (And is where net spend, which is inferior to gross spend for analysis, falls behind £XI, which takes into account talent at a manager’s disposal – not spending during often arbitrary periods of time.)

Even so, it was four immediate expensive buys, without losing any key players in return; and although United appear to be finally clicking, they still languish in 6th place. In that sense they haven’t improved since Louis van Gaal left, although their rivals have all got better this season.

If Mourinho goes on to prove that he is still one of the world’s elite managers, it seems unlikely that he’ll find himself in a league of his own, as it seems that his rivals in England have improved since his heyday a decade-or-so ago whilst he has arguably regressed (as happens with the changes in the game; and I’ll get onto those rivals in due course).

United have the costliest squad in England (£739.4m after inflation) and as shown above, have fielded the costliest £XI this season, at an average of £345.9m. Halfway through the season it’s fair to say that they’ve not had great value so far, even if they are gradually improving.

Mourinho often mocked managers who didn’t make an immediate impact – those who asked for time – so it’s only fair to judge him with his own rhetoric (even if all managers will have circumstances where they need time). Meanwhile, Klopp, with a bit more time in this specific job, is working wonders on half the budget – but at a club where pressure of past glories is also a huge millstone.

The second half of this article is for subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]