5th October 2009

So what does it cost to achieve success in the Premiership? The following is an in-depth look at the costs involved in challenging for the title, and why, based on everything barring history and prestige, Liverpool have no right to expect to be any higher than 4th on any given season.

Using a mixture of data from ‘Red Race: A New Bastion’, updated (2009/10) versions of that analysis and information gleaned from new highly reputable sources, this is a fairly definitive account of the wherewithal required to win the Premiership in the current climate.

For me, it is a must-read for Liverpool supporters, because it is all about putting the expectations into context.

Part of the article is free to all to read, but the 2009/10 sections will be visible only to members.

Money and Success

In their excellent new book, ‘Why England Lose: and Other Curious Phenomena Explained’ (aka ‘Soccernomics’), Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski note that while money spent on transfers does have a bearing on success, it is wages that make the greatest difference: an 89% correlation between how much a club spends on wages and how successful it is (based on data from 1998-2007).

Of course, the best players demand the biggest wages; sometimes this will mean paying a large fee, but it could also mean getting a ‘free’ transfer (that costs £121,000 a week, or £30m in total, as seen with Michael Ballack) or, of course, hanging on to your existing stars who would otherwise be tempted away.

My own data shows that there is actually a strong correlation between success and the money spent on transfers, particularly in the most recent Premiership seasons. Kuper and Szymanski’s sample period of 1978-1997 takes into account the time before transfer spending had such a great effect; prior to the mid-’90s, cheaply assembled and newly promoted teams could win the league. It predates Chelsea’s mega-spending, which effectively ended the hopes of a lower-spending side like Arsenal of winning the league, particularly when big spending is allied to world-class management.

My own Relative Transfer System compares eras in what I feel to be a more accurate way, because it converts fees to a percentage of the then-record transfer. As detailed in Red Race, teams ‘need’ to have an average of 32% of the transfer record to be successful in the modern era; in other words, by today’s terms, the average cost of a strongest XI has to be around £11m per player to land the English title. My research also shows that this figure needs to be even greater to win the Premiership for the ‘first’ time.

Squad Costs

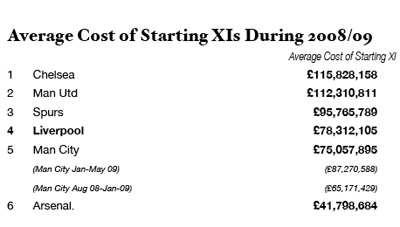

Let’s start with last year’s results from my own research, given that it is a full set of data, gleaned from the entire 2008/09 season. (The number crunching behind this can be found in this downloadable PDF, Red Race Stat Pack.)

Note: the figures used for transfers were meticulously researched, but there will always be discrepancies due to undisclosed fees, estimates, swap deals and countless confusing clauses. In all cases, the maximum payable fee when including all clauses is used; hence Robbie Keane, sold back to Spurs for a minimum £12m, is listed as £19m, because the Reds could end up receiving that amount.

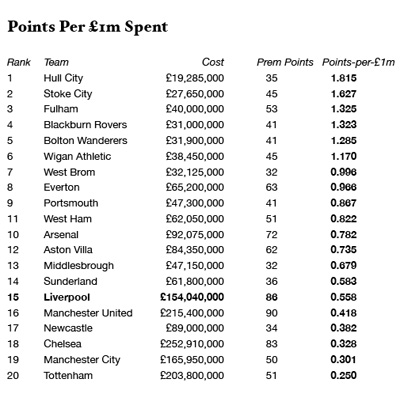

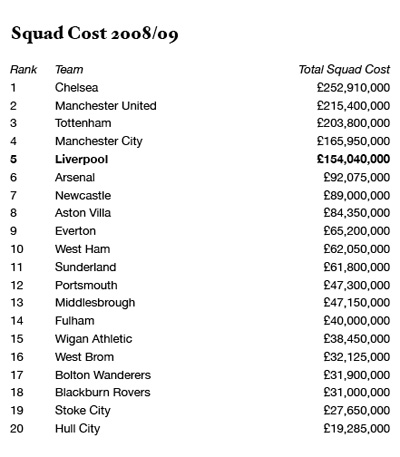

Based solely on the cost of all players used over the course of the campaign, Liverpool ‘should’ have finished 5th in the league; it obviously doesn’t work that way, but it highlights the difference in wherewithal with other clubs.

In the cases of Spurs and Manchester City, it could be argued that the managers were working with a lot of players they didn’t especially want –– particularly so in the case of Harry Redknapp, who inherited a ragtag collection of costly signings. Indeed, the Spurs situation is quite reminiscent of Roy Evans’ tenure at Liverpool, where his own expensive signings were mixed with the costly deadwood of his predecessor, which is never easy to shift without incurring a massive loss, and certainly can’t be done overnight.

[ttt-subscribe-article]

Of course, these squad costs don’t give the true ‘price’ of each transfer at the time it was made. Managers in position for longer will be able to call upon expensive players bought earlier in their reigns, when each £1m went further.

But given that clubs need to spend greater amounts for incremental improvement at the top end of the table –– where there’s less scope to make a difference –– it’s no surprise to see the big four in the lower half of this particular list.

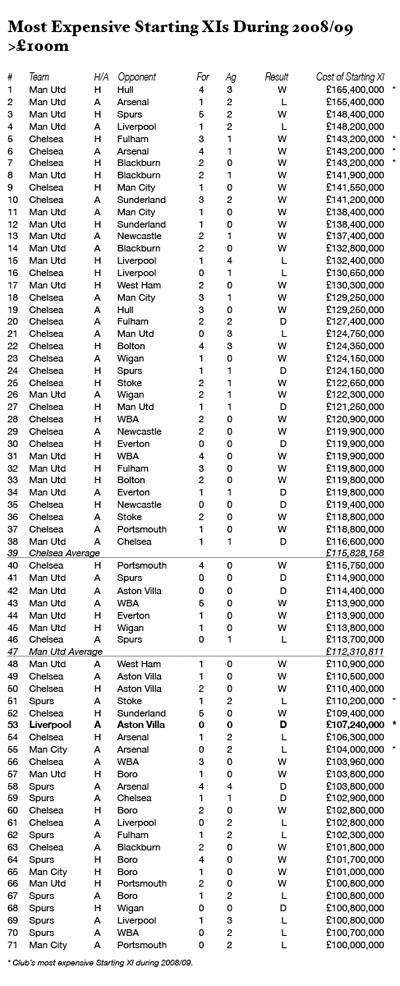

Of course, having an expensive squad doesn’t mean that players were always available; a lot of talent can sit out the campaign with injuries. It gives greater scope to choose from, but what were the most costly sides last season?

The above table includes a ‘before’ and ‘after’ for Manchester City, whose spending increased notably in the winter transfer window, adding £22m to the average cost of their Starting XI, to take it above Liverpool’s.

Wages and Wherewithal

The one big expense that is always overlooked [as backed up by the subsequently published findings of the Soccernomics book] when discussing the wealth of a club is wages. Fans will often make calculations based on transfer fees but fail to consider that a £30m player can also cost £30m in wages over a five year period.

If you don’t have as much wealth as other teams, but are expected to compete, then you need to find special men who put football before their wallet. Fernando Torres is such a player: he has a deep respect for the manager, loves the club and its fans, and has stated that he’d rather earn less money and be happy than be “greedy” and go elsewhere. Of course, he gets well remunerated for his efforts, and earned a pay rise in 2009 that didn’t extend his contract beyond 2013, but which included the option of a further year. Even so, he could have earned a lot more elsewhere, but his character and loyalty had already been seen at Atletico Madrid, where he stayed longer than many expected.

But these types of players –– world-class but humble –– are as rare as Halley’s Comet sightings coinciding with a solar eclipse and a Sean Dundee goal. If it’s hard enough for a manager to find the player he wants, it’s harder still to broker a deal that suits all parties if unable to pay the going rate.

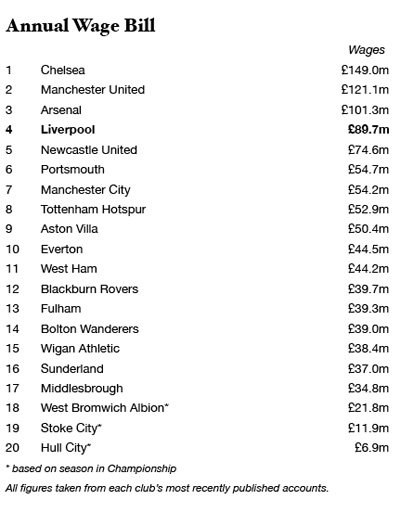

And so Liverpool remain well adrift of the other big payers, as can be seen in the table below, which is based on the most recent set of financial figures in the public domain. Liverpool have handed out a few pay rises to players in the meantime, but the other big clubs have done the same for some of their stars. Obviously the big change since then will be Manchester City, who have handed out £100,000-a-week wages to numerous players in the past 12 months.

All figures taken from each club’s most recently published accounts.

The table clearly highlights the gulf in spending power: Chelsea were paying more in annual wages for the year to 30 June 2008 than the cost of the entire Liverpool squad that ended the 2008/09 season.

One potential problem the Premiership faces is the new 50% English tax law for annual earners of more than £150,000; by comparison, Spain cut taxes in the top bracket to 23% for the first five years of employment –– originally to encourage top business executives to the country, but was expanded to footballers when David Beckham moved to Real Madrid in 2003. This will benefit the big Spanish clubs when it comes to luring the top players (therefore an issue with Liverpool’s battle to retain La Liga targets Xabi Alonso and Javier Mascherano), and also means that a club like Manchester City, where money is no object, can pay extra to overcome the deficit in a player’s pay packet. There were reports of City offering Samuel Eto’o a mind boggling £250,000 a week to try and bring him to the Eastlands from Barcelona, which highlights how far they are prepared to go.

English clubs will now have to increase players’ wages to overcome the shortfall that has occurred since their original contracts were signed –– although in the case of Fernando Torres, Steven Gerrard, Dirk Kuyt, Yossi Benayoun and Daniel Agger, that has already been addressed by Rafa Benítez.

The Current Season – 2009/10

While my research for Red Race looked at the entire Premiership last season, the main interest obviously now lies with the big six – the recently established ‘big four’, plus Manchester City and Spurs, whose spending demands greater scrutiny.

For example, when Liverpool lost to Spurs on the opening day, the Reds’ side cost £95.8m compared with the Londoners’ £135.2m. People can talk all the want about Benítez’s spending, but the fact is he has never been able to have an expensive team, because he’s often had to sell in order to buy.

Harry Redknapp is doing a very good job at White Hart Lane, but he has already been able to field a more expensive side that Benítez has managed in over five seasons.

The results of the research on the present season are currently for members only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]

It will be easy for the critics to blame Rafa Benítez if Liverpool drop out of the top four, or indeed, even fail to win the title, but all the evidence, in terms of wherewithal, continues to point to the fact that, in reality, Liverpool should be finishing further off the pace.