“Liverpool drew all six league games against their closest rivals (City, Chelsea and Tottenham) and failed to score in any of their three cup finals, with successes in the FA Cup and League Cup coming after penalties.”

These two annoying narratives from last season appeared in a Times column just before the Community Shield by the usually reliable Paul Joyce (who may have merely been pointing out these tired criticisms, as he’s not a negative Nelly).

Thankfully I’d already addressed both in my new book This Red Planet: How Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool FC Enthralled and Conquered The World.

Both are very flawed narratives.

Yes, they’re technically true, but it’s technically true that Michael Jordan missed lots of shots (“I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times I’ve been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed”); Lionel Messi misses tons of plenty of penalties; and the world’s best golfers have missed countless putts (albeit few as simple as Erling Haaland’s open goal yesterday).

No one judges anyone by a few things that go wrong in otherwise glorious bodies of work (and Haaland will probably be just fine).

I’ll include some brief excerpts below from the book to show why, as well as adding a few updates.

No one will achieve perfection or even close in a season. There will games where you drop points, but those small number of games need not have any meaning; and there will be games where you draw blanks, from bad luck, just as they’ll be games where you score goals, from good luck.

(Had Nathan Aké not got a glancing head to Trent Alexander-Arnold’s shot, Ederson probably saves it. Had Martin Atkinson still been refereeing, and done the game yesterday, Liverpool would not have got a penalty for a blatant handball, because he stopped giving Liverpool big decisions in 2015. Ederson might also have saved a second shot with his face. Equally, City’s goal could – should – have been ruled out for Adrian having both hands on the ball, but it was given.)

Liverpool won the Community Shield in style (in a pulsating game), to complete Jürgen Klopp’s trophy haul in England, even if it’s a showpiece final and not a big deal. But it felt a big deal once City equalised, and you could see that it was being taken very seriously.

From last season, I’d also rather focus on being only the second major European league team to reach a Champions League/European Cup final when also posting more than 90 points in their domestic league – the first being … Liverpool in 2019.

It was a season of staggering consistency, with just four defeats from 63 games, and 49 wins.

Or the club-record 147 goals. Or the 27 games won (including shootouts) out of the final 32.

Or to end the season the highest ranked team in the world when averaged across the three main ranking models, as I cover in more detail in the Introduction to This Red Planet.

(One of the two losses was a second leg of a tie already won, while one of three draws was in the second leg of a tie already won. The other was a 2-2 away at Man City.)

If you’ve won 27 from 32 games in the run-in, including all kinds of high-pressure games, often three days apart and with tired or heavily rotated teams, to pick fault is like saying Natalie Portman’s eyes are 0.001% wonky, or Brad Pitt once had a single hair almost out of place. Again, both may be true, but not really relevant.

Ian Rush didn’t score against Manchester United until he’d bagged almost 300 goals for Liverpool … against all the other clubs. With those 300-odd goals, Liverpool won all the trophies. It really didn’t matter. (Indeed, once Rush started scoring against Manchester United, they won all the trophies. It was not a reflection Rush, but the randomness of finishing.)

I’m particularly annoyed by the “lack of goals in cup finals” narrative, as if Liverpool didn’t score a ton of goals in major high-pressure games, especially from January onwards.

In the last ten months of proper football (excluding preseason but including the Community Shield), Liverpool have scored ten (TEN) goals against Manchester City and nine (NINE) against Manchester United; as well as, since the start of last season, eight against Arsenal, seven against Porto, six against Everton (the narky derby, obviously), six against Benfica, five against Atlético Madrid, five against Villarreal, four against AC Milan, three against Spurs, and three against Chelsea. That hardly suggested some big-game choking, or a predictability, or lack of killer instinct.

Again, 147 goals; with many scored, as you can see above, against top opposition or in high-pressure games.

Whereas in the cup finals against Real Madrid, and Chelsea, there was some of the best goalkeeping (pre shootouts) that you’ll see. Far better shots than Alexander-Arnold’s yesterday did not go in. That’s why finishing is so random.

Here are some of the numbers of goals the Reds scored in the run-in, including the instances of three or more scored in meaningful games (i.e. not the domestic cups against lowly opposition), plus two or more in the bigger games.

3 – Brentford

2 – Arsenal

3 – Crystal Palace

2 – Leicester City

2 – Inter Milan

3 – Norwich City

6 – Leeds United

2 – Arsenal

3 – Benfica

2 – Manchester City

3 – Benfica

3 – Manchester City

4 – Manchester United

2 – Everton

2 – Villarreal

3 – Villarreal

2 – Aston Villa

2 – Southampton

3 – Wolves

(The last three, while not elite opponents, were very high-pressure games.)

Plus, excluded above are single goals to win a fair few games and two goals to beat lesser opposition (and wins scoring three goals in the League Cup vs lesser sides), with no blanks, beyond the finals, which are worth adding here.

3 – Cardiff City

1 – Burnley

1 – Norwich City

1 – West Ham United

2 – Brighton & Hove Albion

1 – Nottingham Forest

2 – Watford

1 – Newcastle United

1 – Tottenham Hotspur

When Liverpool beat Man United 5-0 at United early last season, United were at that point more of a key rival than Spurs. When Liverpool scored three against Man City in the FA Cup semi-final, no one was saying it was a meaningless game. Had Arsenal scraped past Spurs on the final day, Liverpool had already beaten Arsenal twice (plus another time in the cup). Then not beating Spurs would not have felt so easy to fit into a narrative (and let’s not ignore why Liverpool didn’t beat Spurs at Spurs: horrific officiating, and a cast of Covid absentees. It’s called context.)

I said all this before Liverpool took their tally of goals against Man City since October 2021 to ten (TEN), up from seven.

The fast, swashbuckling Darwin Núñez may add even more goals – he has shown in preseason with five goals in just 80 minutes in total against RB Leipzig and Manchester City – that he can finish, with headers and with his feet, and also create chances and win penalties. But his aim is to help the Reds win games, not to top the scoring charts. There’s already a special energy he brings.

The almost feral, tribal chant of “Núñez! Núñez!” from the Liverpool fans, just when he chases down a lost cause or wins a free-kick, could in itself win more games, as it’s a kind of intimidating noise that will lift the decibel levels at Anfield – in the way the Fernando Torres bounce used to. The randomness is that if Núñez was instead called Aureliano Nepomuceno Sepúlveda, there probably wouldn’t be this instant awesome chant.

There was another narrative too from last season: that all Liverpool achieved was to simply match what Arsenal did in 1992/93.

Which, frankly, was also cobblers.

Excerpts from This Red Planet

Anyway, here’s some passages from the new book:

Anyway, here’s some passages from the new book:

You Don’t Always Get What You Deserve in Life, So You Have To Learn To Enjoy the Ride

After Liverpool lost the final, in a brief foray onto Twitter (to post links to my article rather than bathe in the bile) I stumbled across a Newcastle fan laughing his head off at Liverpool and Jürgen Klopp. “Getting manager of the season for winning two cups on penalties and bottling the Champions League and Premier League”, he noted, albeit I added the correct capital letters, to make it look more like an adult typed it.

It bears repeating: Liverpool won 49 games in 2021/22. Newcastle only played 40 – and won less than a third (13). Obviously there’s no point arguing with idiots on the internet, but it sums up the increasing modern obsession with schadenfreude over self-respect and self-awareness.

People can belittle what was won in the end, but as a body of work – a season of 63 games – it was a masterpiece.

Perhaps the stupidest ‘take’ in the aftermath of defeat in Paris was that, in 2021/22, Liverpool somehow only ‘achieved the same’ as the Arsenal team from 1992/93, which – by removing the context – is like saying that the Man United team from 2009/10 (Edwin van der Sar, Gary Neville, Patrice Evra, Rio Ferdinand, Dimitar Berbatov, Wayne Rooney, Ryan Giggs, Park Ji-sung, Nemanja Vidić, Michael Carrick, Nani, Paul Scholes et al) was only as good as the Birmingham team from 2011, as both won only the League Cup.

That United side, who made the Champions League final the year before and the year after, lost the title on the final day by a single point (to Carlo Ancelotti’s exciting Chelsea, ironically); Birmingham were relegated. Yes, Birmingham winning the League Cup was a bigger achievement than that Man United team winning the League Cup, but it would be comparing apples with oranges. And even then, United’s 2009/10 did not achieve anything historic. Liverpool in 2021/22 did: most games ever won by England’s most successful club in a single season; longest attempt at keeping the quadruple alive, and one of only a handful of clubs to play every game possible; a points tally that would have won the title more often than not in the history of English football; the first English team to win all six Champions League group games; the only time, apart from when they did so in 2019, that a European team got more than 90 points domestically when also reaching Europe’s major final; and much more besides.

Arsenal in 1992/93 finished 10th in the league and didn’t even play in Europe. Anyone comparing Liverpool narrowly losing the Champions League final after winning 28 league games (losing just two) when finishing 2nd, with Arsenal winning a measly 15 (from 42 games, not 38) whilst playing none in Europe, is being really weird. It’s a weak kind of sophistry.

Despite playing four more league games, Arsenal managed just 56 points in 1992/93 to Liverpool’s 92 three decades later, and even if you can’t easily compare eras, then don’t make specious comparisons designed to denigrate unfairly. Arsenal lost four times as many games in the league as Liverpool lost across four competitions.

Despite two long cup runs, Arsenal won fewer games in 1992/93 across three competitions than Liverpool won in the league alone; as well as the Gunners facing the ‘mighty’ Sheffield Wednesday in both domestic finals, rather than the reigning European champions. And it’s not like Arsenal were some small club at the time: they won the title in 1989 (lest we be allowed to forget) and 1991. What they did in 1992/93 was partly possible as they clearly didn’t put much effort into the league, and obviously required no effort for Europe. To go back to an example used earlier in the book, Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields only achieved the same in the charts (no.2) as Shane Richie’s cover of Wham!’s I’m Your Man, but that doesn’t make the two in any way comparable.

Also, a few journalists and football writers who really should know better were seeing a flaw with the fact that Liverpool did not beat Manchester City, Spurs or Chelsea over nine games (sometimes throwing in Real Madrid to make it ten), with the exception of a cup win against Pep Guardiola’s men; so, just one win in those games, even if two more were won on penalties.

Yet City likewise didn’t beat Liverpool, and more startling (if you want to make this kind of tenuous point), City lost twice against Spurs, who finished 4th, while Liverpool were unbeaten against them. That’s five games against Liverpool and Spurs for City, with three defeats and two draws. And, if you want to again focus on just the clubs where Liverpool dropped points, you could do something for Man City and create a mini-league including Crystal Palace, Liverpool and Spurs, and City would be bottom, having won none of the seven games, and lost four. But that’s not how football works. There will always be teams, like Chelsea and Man City for Liverpool, and Crystal Palace, Liverpool and Spurs for Man City, where a clash of styles might negate what would be considered the better team on paper, as well as any misfortune on the day. Had City not staged their late comeback against Aston Villa, no one would mention the points Liverpool dropped against Spurs; and everyone would instead focus on Spurs doing the double over City as proof of something inherently wrong with Guardiola’s team.

Liverpool, in addition to getting 92 points, had a European run where they beat AC Milan twice, Inter Milan (Italian champions and last year’s champions), Atlético Madrid twice (reigning Spanish champions), Villarreal twice (reigning Europa League champions) Porto and Benfica – with the Portuguese league not elite, but also, traditionally relatively strong. They also tore City apart at Wembley in a semi-final, to go 3-0 up at half-time.

If making random mini-leagues, or looking at other top six teams – the Big Six, it transpired again, just in a slightly different order than other seasons – then Liverpool beat Arsenal twice (three times if you include the cup) and thrashed Man United 9-0 across the two games. For all their extra money, Man City finished one point ahead, won fewer trophies and didn’t get as far in Europe. It doesn’t say too much about them, and what they’re made of, that they lost both games against Spurs, took just a single point against Crystal Palace, and could not beat Liverpool over three games – or that they lost to Real Madrid on aggregate. They got 93 points to Liverpool’s 92.

Once you’re past 90 points then you’re really splitting hairs to focus on games not won, given that 90 points means relatively few have been dropped, and total perfection remains impossible. To get 90+ points – historically almost always enough to win the league – and to find fault is a bit like griping that Liverpool didn’t beat Crystal Palace 10-0 in 1989 instead of 9-0.

The Randomness of Not Scoring In Finals

With pure irony, John Muller of the Athletic wrote that, “On another day, in some other timeline, maybe Real Madrid could have won the 2021/22 Champions League final.

“It would have been improbable in any universe, with the way Carlo Ancelotti’s team played, but you can imagine some alternate reality where the movements of bodies and balls are just a little less orderly, where football is a little less fair – who knows, maybe stranger things have happened in a world like that than a smash-and-grab 1-0 win.”

The article was entitled: Only in an alternate reality should Real Madrid be Champions League winners – that’s the beauty of football.

It ends with Muller stating a 5-1 win for Liverpool played out in the real universe: “No one could argue the result was unfair. Liverpool had the better of possession, field tilt, shots, and expected goals. They’d played the game in an organised 4-3-3 and pushed into Madrid’s half, while Ancelotti’s lopsided shape, meant to test the space behind Alexander-Arnold with the Vinicius-Benzema pairing, never really created much threat.”

As such, it’s slightly worrying to discover that, according to official reports of the game, we live in an alternate universe, but clearly it had been a weird season.

In his post-match analysis for TTT, Andrew noted: “A brilliant article by [analyst] Mark Taylor which I often refer to came to mind. He showed if one team has lots of low-grade chances but the other team has a couple of good ones, the latter is more likely to win. So I put the shot values from last night in to the simulator.”

What he found was:

A) it was incredibly likely that Madrid would score once from their chances; and

B) it was also more likely Jürgen Klopp’s team would score four times rather than none.

“And”, he continued, “they had so many shots on target too. Mohamed Salah alone had six. It’s the most he’s had in a game for Liverpool and from the available data (which isn’t great for his early career), the most he’s ever had for anyone. The preceding two Champions League finals saw eight on target efforts in total [so, four teams’ totals combined], yet the Reds had nine in Paris. To put it into context, there were 29 instances of a team having nine shots on target in a Premier League game this season. Those sides averaged 2.9 goals and 2.45 points per game. Not one of them failed to score and only twice were they beaten. Stellar Courtois, eh?”

Regarding the points made in A and B, it’s hard to create lots of ‘open space’ big chances (like Madrid’s goal) when you’re playing against a packed defence. Those ‘big space’ goals often come on the break. Real defended deep to prevent one-on-ones (although Salah still got in), which made sense; they also defended set-pieces deep, which seemed to confuse Liverpool – for all the success of neuro 11 in terms of penalties, the set-piece deliveries under pressure were very poor in Paris. Liverpool had a massive height advantage at set-pieces, yet did not make use of it.

If a team doesn’t give you the time and space for big chances, you have to work a lot of ‘pretty good’ chances, which Liverpool did, and hit them well, which Liverpool (mostly) did; but if the keeper gets a hand, arm, knee or nose to everything, it can be hard to pick fault. Salah, Mané and Díaz jinked past defenders, and got shots away, and on another day they’d have resulted in goals. After all, Liverpool had scored 147 up to that point, so it’s not like there was suddenly a need to have a 50-goal-a-season traditional no.9. (That said, Liverpool did soon go out and buy Darwin Núñez, but had not been expecting Sadio Mané to leave until learning of his plans on the eve of the final.)

Even in the first cup final of the season, Edouard Mendy made a frankly incredible double-save against his Senegalese compatriot, with the second effort as he scrambled to his defeat defying belief; Mané’s effort deflecting over, in much the same manner that Salah’s best shot was somehow kept out by Courtois.

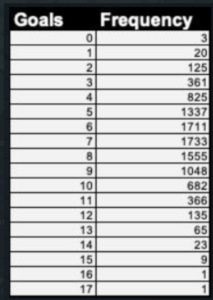

Dr Phil Barter, a senior lecturer at Middlesex University, worked with Anfield Index to run a Monte Carlo simulation to calculate the likelihood of the Reds scoring zero goals in the three finals from the quantity and quality of shots. It found that from the 10,000 ‘runs’ the algorithm sped through, only three times did the Reds draw a total blank. In other words, 9,997 times out of 10,000, Liverpool would have bagged at least one goal. Indeed, the most likely total was seven, which came up 17% of the time; and 15 goals, as a possible outcome, came up three times as often as zero goals.

Because football results can be incredibly random.

(Important news for subscribers only follows in the comments below.)