As I’ve been saying all summer, vital players – often leaders, not just regular footballers – valued at hundreds of millions of pounds have returned from injuries, and the new and often improved contracts to the key personnel was more vital than adding shiny new signings.

Jürgen Klopp has made it clear that he wants unity, stability, and to work with the squad he has assembled. Does he want to waste time having to train new players to do all the things the existing players took years to learn, and from which they will continue to improve and benefit?

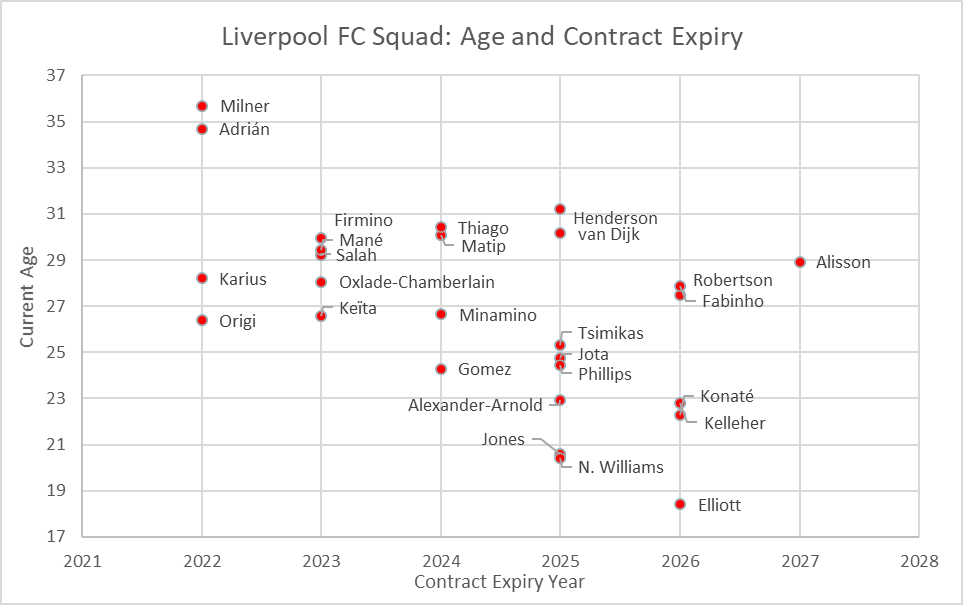

Add the one new big buy, Ibrahima Konaté, and the Reds have now tied a staggering 12 first-team squad players down to long-term new deals, and of course, the negotiations don’t have to end with the transfer window; new deals for the Terrific Trident will be negotiated. As it stands, no fewer than 14 of the Reds’ first-team squad are contracted until 2025, and six to 2026 and beyond.

New deals signed so far, with potential first-XI players in bold:

Adrián – 14 June 2021

Caoimhín Kelleher – 24 June 2021

Ibrahima Konaté – 1 July 2021

Harvey Elliott – 9 July 2021

Trent Alexander-Arnold – 30 July 2021

Fabinho – 3 August 2021

Alisson – 4 August 2021

Virgil van Dijk – 13 August 2021

Andy Robertson – 24 August 2021

Jordan Henderson – 31 August 2021

Nathaniel Phillips – 31 August 2021

Rhys Williams – 31 August 2021

Seven of the 12 (thus far) getting new deals this summer started against Chelsea, while Konaté and Kelleher were on the bench. After the £100m+ losses through Covid, there was also the loss of certainty; deals were harder to renegotiate for a club that balances its books until it was clear that fans would be back in the stadia.

The below graphic, by Andrew Beasley, is a stark contrast from just a few months ago, as players get moved from the 2023 line to the right-hand side of the graph. (The aim now is to update as many of those left on the 2023 expiry date, too.)

Stronger Than Ever

I genuinely believe that this is the strongest squad Liverpool have ever had.

Kelleher is a superb young keeper; better than any backup in years. Liverpool have added the prodigious (and giant) Konaté, to provide the best four centre-backs I can recall the club ever possessing.

Nat Phillips has emerged to be the best 5th-choice centre-back at any club that plays a back four (clubs that play three central defenders may have more options, as they need six centre-backs, at least). Phillips was effectively a nobody 12 months ago; now he’s a cult hero. In all the setbacks of last season, he benefited, becoming a proper Premier League player.

Against Chelsea, Liverpool fielded what could be close to a strongest XI, but on the bench were Diogo Jota, Ibrahima Konaté, Thiago Alcántara, Naby Keïta, Joe Gomez, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain, Takumi Minamino, Kostas Tsimikas and Caoimhín Kelleher. Wow! Has the bench ever been stronger, unless the first-XI players were being rested?

For various reasons, not even in the expanded 20-man squad were Curtis Jones, James Milner, Divock Origi, Nathaniel Phillips, Neco Williams, Rhys Williams and Kaide Gordon (plus Adrián). Many of these are at the level of player who, a couple of years ago, would make the seven-man bench. Now they can’t even make the nine-man bench; and if they did, excellent players would have to drop out.

Ignoring the often mindless obsession with new signings, can you honestly say that Liverpool have ever had a stronger squad? And as I will show, there is more depth and variety than when racking up 97 and 99 league points.

I won’t go into the benefits of how the club is currently run, but you can read more about that in my piece that covered the madness going on at other clubs in 2021, and how it seems that, mostly, it’s the oil-backed clubs that are thriving.

Didn’t replace Gini Wijnaldum?

To me, this is a fallacy, as at the start of last season, Liverpool had Wijnaldum, but no Thiago.

Then Thiago arrived, which could almost be seen as like Liverpool buying John Aldridge six months before Ian Rush left to Juventus. For a while, Liverpool had both players, and then there was only Aldridge for the remarkable 1987/88.

There was no Harvey Elliott either, as a kid sent out on loan. There was Curtis Jones, but he wasn’t really part of fans’ thinking. So, Thiago, Elliott and Jones are now strong parts of the equation that has seen Wijnaldum go. As great as Gini was, that seems like an upgrade overall.

Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain was also missing – out until the second half of the season. Like Naby Keïta, he needed a good fitness guru to sort out his issues; midway through 2020/21 Klopp said Liverpool had hired the “number one in Germany” in new Head of Recovery and Performance Andreas Schlumberger.

The emergence of Jones means a strong 20-year-old midfield option; the signing of Thiago occurred a year before Wijnaldum departed (if Thiago had arrived now, everyone would think Wijnaldum had been replaced!); and the prodigious talents of Elliott suggest that Liverpool have far better midfield options than in the recent past. Jones and Elliott are surely only going to improve.

I think Man United have obviously got a top talent on their hands with Jadon Sancho, and I’m not making the comparison in the longer term, but so far this season, Elliott, aged just 18 and at £3m and a bag of tracksuits, has outshone Sancho, 21, at £73m. Sancho has to learn to fit into United’s system, and to play with the brand new pressure of a £73m price tag, as well as overcoming some disciplinary issues in his career so far (a habit for being late to training or returning from international duty). He’s even played less professional football in England than Elliott.

Again, Sancho may end up as the next Ryan Giggs at United – the lad has ability and pace to burn – but if Elliott keeps playing like he has, and indeed, improves with age and experience (as you’d expect), Liverpool won’t need to have paid £73m for anyone.

Elliott at 18 is good enough to be contesting Man of the Match awards against big bruising Burnley bullies and the European champions; Elliott at 21 could be mind-blowing; especially in a team that he has grown up in, where everyone knows each other’s game. Elliott in just three months’ time could be a step up from what we’ve seen so far.

Again, had Liverpool just paid £47m for Elliott from a Bundesliga team – after he was rated as one of the best five teenagers in Europe last season – then everyone would be overjoyed. It’s all a question of framing and anchoring: frame things the wrong way, because of anchoring to a certain idea, and you can miss the glorious reality.

Take it further. If, this summer, Liverpool had paid £350m for van Dijk, Matip, Gomez, Thiago, Jota, Oxlade-Chamberlain, Jordan Henderson and Keïta – who missed huge chunks of last season, if not virtually all of it – then people would view things very differently. Even better than new players, they are integrated players. (A reminder: Jota played only a third of the available league minutes.)

There’s this idea that new is always better; but the most comfortable shoes are the ones you’ve been wearing for a while; ones that, day after day, increasingly suit the shape of your feet. If they’re not falling apart at the seams, they are perfect. New ones that look better but give you blisters are not exactly ideal.

Not enough strikers?

Again, Liverpool’s strikers in the first half of the record-breaking, title-winning season were Mo Salah, Roberto Firmino, Sadio Mané and Divock Origi, with the much-melted Daniel Sturridge having left after playing a very small part on the road to winning the Champions League the season before.

Taki Minamino arrived, and has yet to really fire, but is now probably finally used to English football. He is what most good squad players are: talented, eager and professional, but humble enough to bide his time. (He scored the same number goals for Liverpool in the first half of last season than Sturridge, a superb finisher, managed in a full final season of 27 appearances.)

However, the key addition has been Diogo Jota, who scores non-penalty goals faster than any other Liverpool attacker; even more regularly than Salah. The main three have insane fitness records, which makes it hard for understudies to settle into the team, but Jota is so good that it’s any three from four.

Divock Origi remains, and I want to point out how easy he is to overlook. He didn’t feature in 2018/19 until December (and that goal), and only really got a run of games in the run-in, where he was vital. Then the season ended. Ditto 2015/16 when he ended the season on fire, until he had his leg broken. Each time the next season started with Salah, Firmino and Mané, and why wouldn’t it? Indeed, he scored against Norwich in the opening game of 2019/20, and was still dropped. It’s tough, but that’s life.

Origi almost never gets a run of games to get fitter, sharper and stronger, and to relax into the role (anyone who has played sport knows that it’s easier if you get a run of games and just relax, rather than trying too hard with every rusty rare start or six minutes as a sub). He never gets to find playing rhythm, as a consequence of the Terrific Trident having played over 500 games for the Reds between them. Few players would look good playing only once a month. When Origi has had a run of games he hasn’t let the team down; far from it. Again, he was absolutely irrelevant at the start of December 2019, yet came to define that season. That’s how it can work with Klopp: players come in from the cold and, if they get a run of games after some shaky moments, do the business. See Nat Phillips and Rhys Williams last season.

Liverpool have better striking options than in 2018/19 and 2019/20, the two best seasons in the club’s recent history (and possibly its entire history, given the points tallies involved and the European Cup). Now, rival clubs are spending £100m at a pop on their strikers, or bringing superstars in on £500,000-a-week – but Liverpool can’t do that.

If you live life with a compare and despair attitude, it will wear you down. Liverpool cannot stop what their rivals do. Going into debt to keep up with the Joneses is a dumb way to live.

When the Reds spend nothing in 2020, Man City spent £120m on two players; and had a bad season. Those two players did much better in 2020/21, once settled. Buying for the sake of it helps no one; see Man United’s panicky usurping of Alexis Sanchez from Man City, who did far more harm to United than good.

People never get it, but you can subtract when you add: you can lose cohesion, shared understanding, and you can see the wage bill distorted by a new arrival. Sanchez not only failed, but he pissed off all the other players, who wanted pay rises, to match his mega-deal.

I learnt this lesson in 1997, when I felt Paul Ince’s grit would help the Reds’ midfield; but the loss of John Barnes’ 99%-possession meant Ince was often winning tackles just to retrieve balls he lost. Ince had qualities, but Liverpool were no better overall, because in adding Ince’s steel they lost control of the games.

Egos-A-Go-Go

Anything you add into an ecosystem can change that ecosystem in unexpected ways, and anything you add into football’s egosystem can change that egosystem. It’s much easier to disrupt an utterly united group of players than to improve it.

New players can upset the applecart, disrupt the wage structure, and cause all kinds of issues, if they are not right; and finding the right players is not easy. Liverpool’s transfer success this past decade or so has been due to limiting their own options, to avoid toxic talent; Brendan Rodgers took a gamble on Mario Balotelli, and rather than help, he helped ruin a season. He ruined training. He ruined the atmosphere. He was a good laugh at times, but a pain in the arse more often.

A lot of players fail the Reds’ current “no dickheads” test, but it’s not just the players: parents or siblings who are overbearing in inserting themselves into the picture; agents who are disruptors, eager to constantly cause unrest to move their players on; entourages who get in the way of the actual football. Liverpool avoid dickhead players, but also dickhead families, dickhead agents, dickhead entourages. Dickheads are distractions, after all.

Instead, the Reds make fewer signings, but develop the players via a system of intense training, world-class coaching, clear-eyed tactical visions and shared values and understandings.

For example, at the end of last season people told me Kostas Tsimikas was garbage; but a proper preseason, after a year of adjustment, and he’s a different proposition. Just wait, I told people four months ago. He could yet adjust. The more time with this group of players, playing in this league, training intensely every day, under Klopp and Pep Lijnders’ tutelage (having overcome Covid and a bad knee injury), and see what happens.

Now, Man United are getting all the headlines for re-signing Cristiano Ronaldo, who was clearly one of the great of the English game first time around. (I can’t stand the guy, but he was brilliant for them, after a slowish start.)

But he’s nearly 37 now, and instantly the top-earner at a club where others will work harder.

When you buy an ageing superstar who does no running on the pitch, you have to factor in what you lose, as well as what you may gain.

As noted above, every player you add has the ability to not just improve things but also to subtract from the team, when the sport is maxed out at 11 players; each new signing has to replace someone whose qualities may be missed, but the key is if the new addition may add more.

Individually the big new name may thrive, and their presence may give others a lift. They’ll sell more shirts, for certain.

But if you buy a player who is on too much money, and is too high-profile to drop despite being in the melt-zone, what then? In fairness, Zlatan Ibrahimovic and others have defied Father Time exceptionally well, but older players come with more risks. Any player can get a serious injury, but only players in their 30s tend to “melt”. Phasing out iconic players is almost always a messy affair.

Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi still score a lot of goals (albeit from taking a lot of shots and penalties that other players could be taking), but they do the least work of any strikers.

In a team sport, you lose the pressing and the running into spaces, and football is not like basketball where an individual can carry a team.

Big names can inspire, but they can also hog the ball, hog the limelight, and unbalance the egosystem. Too many big egos and a squad becomes a powder keg.

Plus, how do you phase out a superstar whose legs are going, and who won’t take kindly to some kind of managed decline? (It went badly with Steven Gerrard at Liverpool, while Kenny Dalglish had the luxury of managing his own reduction in playing time, as the boss.)

Ronaldo is in great shape, but can it really last that much longer? Maybe, but the odds are that it won’t.

In that sense, are some clubs signing impending problems, rather than solutions?

Attack!

A low-key signing made back in February (ancient history, which means it doesn’t count) could prove another gem within the next 12 months. And while he may not feature much in the league in 2021, Kaide Gordon is the best 16-year-old Liverpool have had in donkey’s years; with the exception of Harvey Elliott.

I also see zero decline in Sadio Mané, with his pace and ability to go past players clear, and his goalscoring form at the end of last season, in preseason, plus a goal already in the Premier League, suggest there’s no decline. He looks as good as ever – and that’s a one-in-three scorer who does so much more than that. He’s sharp, inventive, hard-working, and stretches teams. His pace hasn’t dropped one bit.

Strikers’ seasonal tallies often vary, and he doesn’t take penalties (or even free-kicks) to bolster his numbers and get him out of dry spells. If he’d taken (and scored) Liverpool’s penalties last season, no one would mention that he doesn’t score enough goals; ditto Roberto Firmino, who also ended last season on fire, had a great preseason, and had scored in the league already before what seems a minor hamstring injury.

Both had a confidence dip in front of goal last season but their attacking play often remained excellent. If you only judge players by their goals you miss all the ways they help others to score and to win games. And last season they were playing in much-weakened XIs, lacking leaders, and all the set-piece giants.

(Again, the correlation between Firmino scoring from set-pieces and Liverpool fielding giant centre-backs is clear, as I showed several times last season, prior to him scoring from set-pieces once Liverpool switched to the giant Rhys Williams and the bonkers, ball-nutting Phillips. Only van Dijk has scored more set-piece goals for the Reds than Firmino since the summer of 2018, and both are in double figures. But without the big guys, Firmino, at 5’11”, becomes easier to mark and nullify. And people don’t tend to notice that quite a few of his goals come when Virgil van Dijk and Joel Matip are being crowded and fouled, or when someone like Rhys Williams, just via his presence, was dragging several men away.)

I know I’ve gone over this ground before this summer, but the story never changes: Liverpool have to buy new players is the constant mantra.

No. Liverpool are a team built on small numbers of signings, gradual integration, extreme professionalism and motivation, and improved interplay; within a tightly-managed and heavily incentivised wage structure that seriously rewards success, and not mediocrity.

Indeed, after the hell of last winter – endless lockdown, soulless stadia, never-ending injury list and for Klopp, the death of his mother and a funeral he could not attend due to Covid restrictions (ditto Alisson and his father) – and we should be counting our blessings that Klopp is still at the club, as I feared he looked close to burnout. (As we all did, often without those added stresses.)

In time there will need to be new signings, and maybe some shakeups behind the scenes, but for now the squad remains at a great age. And it can be a gradual evolution over the next couple of years.

It’s easy to want new things, but in the case of Klopp, and players like Alisson and various others, a proper break to recharge and decompress may be the most valuable benefit of the summer. As ever – such as the total fanbase meltdown when Coutinho was sold, and when the club preferred to wait five months for van Dijk instead of signing someone else, and when people thought Andy Robertson was a waste of £8m, and the lack of a ‘proper’ signing before 2019/20, etc. – it’s often best to wait and see.