Despite the latest questions surrounding Man City’s troubles with UEFA and Financial Fair Play dating back to 2018, when Der Spiegel released many leaked documents, it’s only since the demolition of Watford in the FA Cup final – reducing the competition to a farce – that City have been clobbered left, right and centre by the media. Or at least, some of the media, while the rest employ cognitive dissonance and just talk about the beautiful passing.

So, before we switch our focus to the Champions League final and leave domestic issues to one side, I thought the timing was right for the latest instalment of our Transfer Price Index (TPI) project.

(David Fitzgerald has also written this piece for TTT about FFP in general, while earlier in the week I published this piece about City’s greed, and the scale of the backlash they faced.)

For ten years Graeme Riley and I have been working on TPI – which tracks football inflation. Our work has been used in books, academic studies and even a European commission. It’s not a full-time undertaking but instead something we do in addition to other work, and as such, we update it as and when we can, and use it on this site as our benchmark for spending analysis. While we are avid Liverpool fans on this site, the system we employ is 100% neutral.

And we now have the data from 2018/19, so – with the furore surrounding City – it was time to have a look at just how great their financial advantage was, and how that helped them retain their title; but also, how City compare with Chelsea of 10-15 years ago, the Premier League’s other infamous Sugar Daddy club. And on that score, the good news for City, if they care about the comparison, is that they did not spend as much, relatively speaking, as Roman Abramovich and his pet project; the difference is that Chelsea’s spending came before FFP (indeed, it helped force the creation of FFP), and that actually, Chelsea’s spending has slowed massively since FFP, meaning that they appear to be trying to comply.

None of the figures used are subjective; they are objectively created by the formulas relating to English football inflation. This concept was not designed to criticise City, as it was created before they’d even finished in the top four in the modern era (many blue moons ago). It was not designed to make Liverpool look good – indeed, it was initially designed to help us compare how much a Liverpool player in 1992 or 1995 would be in what was then 2009 money. Once we’d done it for Liverpool, it seemed obvious to apply it to all clubs and all players.

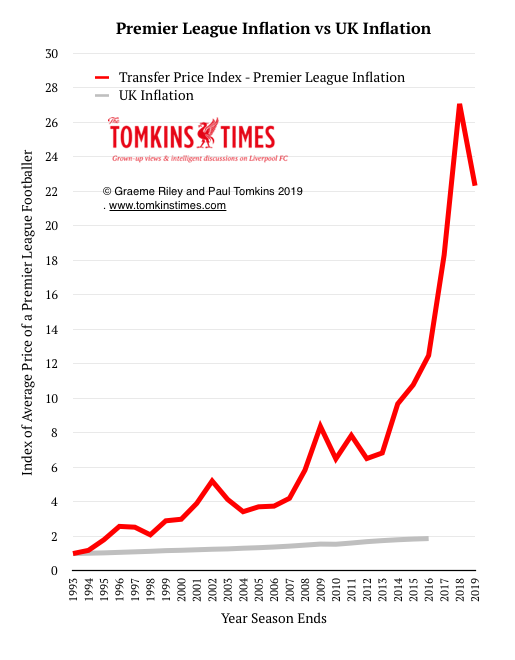

This has also been a season of deflation. For the first time since 2013 the average price of a Premier League footballer fell; with the average price having previously trebled between 2014 and 2018. (And remember, football inflation runs at 10-15x the speed of economic inflation.)

In other words, anyone bought in 2014 for £20m equated to £60m in the 2018 market. But in the 2019 market, after some deflation, that £20m would be £46m; so still more than twice the level it was in 2014. If a lot of money is paid for a player in an inflated market, then it makes them relatively less expensive in the grand scheme of things – because everyone else was paying big money. He will always remain relatively expensive. If a lot of money is paid for a player in a depressed market, then it makes them relatively more expensive, as they were bought when other clubs were strapped for cash. He will always remain extremely expensive. Analysing inflation puts what was paid into context.

The depressed market is interesting. Between them, Spurs and Man City bought one single player (Mahrez), and Man United made just one big signing (Fred). Arsenal’s bigger spending happened the season before, and Chelsea didn’t really go mad. Liverpool obviously reinvested the massive pot of Philippe Coutinho money. The spending of the big clubs looks set to ramp up ahead of next season, and even Chelsea, with a transfer ban, already had Christian Pulisic pre-signed. But without big hikes in the TV money – which always drives the inflation (at least for non-Sugar Daddy clubs) – there may not be many outrageously big-money signings.

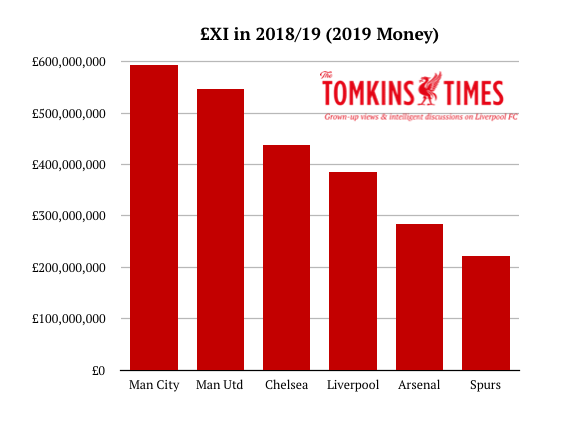

For ten years we’ve used the £XI model created from the data. The £XI is the average cost of a team’s starting XI over the course of all 38 league games, when inflation is applied. It correlates more closely to success than the overall squad value – because of who makes it onto the pitch – and shows that since Arsenal in 2004, every champion bar Leicester has had an £XI that ranks in the top three. This past season, Liverpool ranked 4th; City top. (And remember, City’s £XI only includes a few appearances by their 2nd-most expensive player after inflation, Kevin de Bruyne.)

Squad value is still important, because an £XI can only be formed from players within that squad; but the £XI does not penalise for expensive players who were out injured, or out of favour, or spend half the season out on loan.

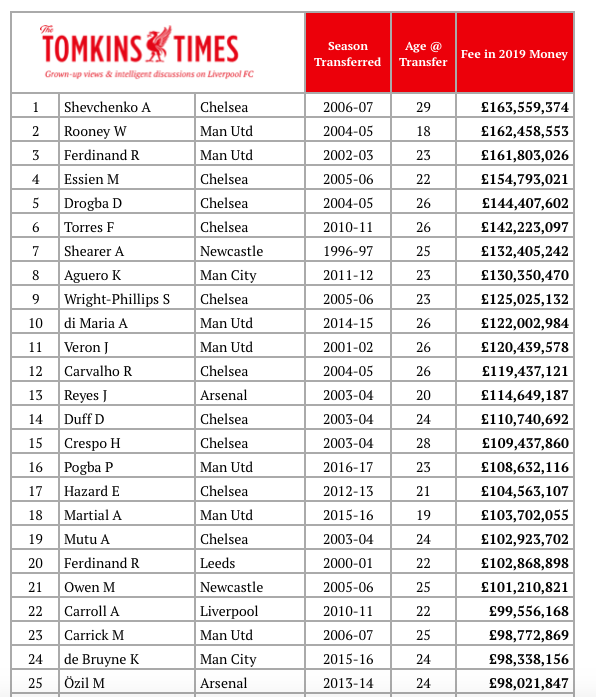

De Bruyne is an interesting example. In 2018 money he was a £120m player; but compared to the current market, which has slumped, his transfer fee equates to £98m. So while City fans may argue that, at £55m, the Belgian didn’t cost as much as Virgil van Dijk, £55m was a hell of a lot of money in 2015 – and more than £75m in 2017/18. And that’s how inflation comparisons work. That £55 has risen to almost twice what it would have been this past season. Hence, Riyad Mahrez, in TPI terms, remains a £60m signing, while de Bruyne is now £98m. Yet without inflation, Mahrez is the costlier player – which is clearly wrong in logical terms, based on talent and age at the time of purchase, with de Bruyne one of Europe’s hottest prospects in 2015.

Meanwhile, the £38m City paid for Sergio Agüero in 2011 now equates to £130m. The £42m paid for Eliaquim Mangala is now £87m, but of course, he’s not in their £XI totals as he never played. That said, Liverpool do not have the luxury of an £87m player who cannot get in the squad. (With inflation, City’s squad is £1.1bn, Liverpool’s just under £700m.)

So the idea that de Bruyne “only” cost £55m is false. Prices rose so much in the years that followed his purchase that it’s easy to forget just how expensive he was within the season he was bought; but adjusting for inflation corrects that. So when City fans say they haven’t spent as much on a midfielder, a defender or a striker as certain other clubs, that ignores inflation. They harvested players at an earlier date, paying a lot of money in a less-expensive era (and as shown, when the average price of a player trebles in just four years, you can see every single season as an era in itself). City spent more than their fans care to acknowledge.

Of course, inflation also shows that Andy Carroll, from 2011, cost £99m in 2019 money, although he is no longer part of Liverpool’s team – and unlike de Bruyne, was a total bust; but Carroll was bought with the £142m received for Fernando Torres. Liverpool also lost Raheem Sterling to City for what currently equates to £88m. And this is obvious, as you couldn’t buy an English international of Sterling’s age and potential, as it was in 2015, for as little £49m in 2019 – certainly not from a top four rival.

The only seven players in the Premier League era to cost more than Agüero after inflation are, in descending order: Andriy Shevchenko to Chelsea, Wayne Rooney to Man Utd, Rio Ferdinand to Man Utd, Michael Essien to Chelsea, Didier Drogba to Chelsea, Fernando Torres to Chelsea, and Alan Shearer to Newcastle. (Kevin de Bruyne ranks 24th.) It would need someone to be bought by a Premier League club this summer for £130m to break into the top eight, with Agüero actually the most recent addition to that top eight.

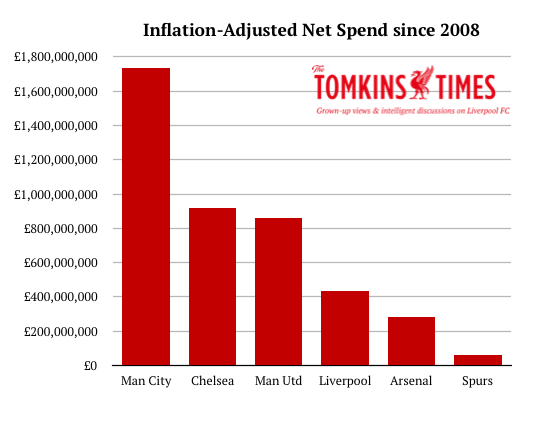

Of course, this does also indicate that City are not the biggest spenders in the entire Premier League era. City are by far and away the biggest spenders of the FFP era, but not of the past 20 years.

Indeed, in 2006/07 Chelsea’s £XI (with the £XI always in current-day money) was £823m, whereas City’s this season was £594m, ahead of Man United’s £547m. But Chelsea now rank 3rd at £437m, which shows the power shift from the darker Blues to the lighter Blues, as the London club seek to cut their cloth according to FFP.

By contrast, Liverpool’s £XI was ‘just’ £386m – with City’s £XI over 50% more expensive. Liverpool aren’t paupers, but the financial gulf is still massive.

Perhaps the best analogy for random net-spend cutoff points, and taking inflation into account, is someone who buys a mansion five years ago for £500,000, and now that mansion would cost £1,000,000. Not because any work has been done to improve it, but because of changes to the market. (Remember, these are not worth the players are now worth – these are the fees from the time converted into 2019 money.)

If you bought a mansion in 2011 and another in 2015 then your net spend on mansions since 2016 can be £0. But you still have two mansions. Which is why arbitrary, short-term net-spend arguments are so fatuous.

If I spend £100,000 on a semidetached house in 2018, then my net spend on houses since 2016 would be higher than yours, but you will have two mansions and I’d have a semi (insert your own rude joke here).

Also, how did you pay for your mansions? I bought my semi by selling my previous property, a terraced house. You paid for yours by someone giving you an artificially high price when selling low-value properties, or just by handing you a wedge of cash.

So net spend can be a very poor argument, but better than gross spend, as gross spend ignores what you have lost.

And net spend really needs a longer period of time to be taken seriously, otherwise you can just cut it off after one year and, as shown above, players bought before – who still make a huge difference – get excluded.

Or, if you want to talk about 12-month net spends, was the only player to play for Man City this season Riyad Mahrez? If so, I’d like to see Mahrez on his own against Alisson, Xherdan Shaqiri, Fabinho and Naby Keïta. Unless a team gets rid of all its previously purchased players, a year of net spent is just utter nonsense.

That’s why the £XI is better – it looks at who you have playing for you, and how much they cost after inflation. It has no arbitrary cut-off points.

But if you want to use net spend, make it a big sample. Let’s go back to 2008, when City were first financially doped. What’s clear is that, in the past 11 years, City have absolutely blown everyone else out of the water on inflation-adjusted net spend. With FFP looming, Chelsea cut back; while Man United lost some big-name players in that time, including Cristiano Ronaldo, which reduced their net spend.

And this is the key point. Man City have been raided by precisely zero predators; while even United lost someone they wanted to keep to Real Madrid. The only players City have sold have been surplus to requirements, or who have faded through age; unlike Liverpool with Xabi Alonso, Fernando Torres, Javier Mascherano, Luis Suarez, Raheem Sterling and Philippe Coutinho. That’s £800m of transfer fees in 2019 money. But that’s also a massive talent drain, that City have simply not faced.

Liverpool have raised funds by selling players who were picked off by richer clubs like Barcelona, Real Madrid, Chelsea and even City themselves; City have not. No one has bullied City, as they have too much money to be bullied.

If City have indeed been paying additional hidden wages – as alleged they did with Roberto Mancini (and if true, why would it stop there?) – to attract and/or retain players like Agüero, David Silva and de Bruyne, so that no one else can try and snaffle them away, then that is totally at odds with FFP rules and unfair to all those clubs abiding by those rules. That’s why it’s such a huge issue. And of course I am biased; their wealth has directly affect my club, and if that wealth meant cheating to spend even more money, of course I’ll feel angry. It stops feeling like an unfair fight and starts to feel like a rigged fight.

If large-scale cheating has kept other teams out of the Champions League spots or stopped them winning titles (yes, even Man United in 2018), those clubs have been massively financially harmed in the process, doubling-down on City’s advantage. Another analogy is if someone steals £1m, and invests it various savings accounts: it legally accrues interest, but the original money was illegally sourced. In the case of the Premier League, any potential financial cheating helps to reap further financial rewards, but worse than that, it denies it from competitors, thus extending the gap. And with money so clearly linked with success, that is why this is such a scandal.

Even if the rules do indeed suit some of the richer clubs, the rules are the rules. You may not think it fair there’s a 20mph speed limit near your house, but there’s a school down the road, and if you buy and tax a car, and obtain a driving licence, you agree to abide by the rules and laws of the highway code. If you get caught doing 100mph you get docked points and possibly even go to jail.

You can’t have 19 clubs playing by one set of rules and one other club playing by its own rules; especially if that club then mops up every single domestic trophy, and all the additional prize money to then “legally” become richer still. As seen when they spilled onto the pitch, City’s technical staff appears bigger in numbers than some major companies, and they have an absolutely elite manager. They play amazing football, but is it fairly funded?

This season, to reach the Champions League final and finish with 97 points in the Premier League, Liverpool played no fewer than 12 games against richer clubs (13 if you include the League Cup defeat to Chelsea). City played none. As brilliant as the football City play is, let’s remember that context.

Liverpool had to get past PSG, Bayern Munich and Barcelona to reach the final in Madrid, and even though we can’t apply our inflation model to overseas clubs (as they will have their own monetary ecosystems), all three almost certainly would have much higher £XIs than Liverpool. (Indeed, based simply on their sale fees from Liverpool after inflation, Coutinho and Suarez alone equal almost £300m, which is 75% of Liverpool’s £XI. Add other starters Arturo Vidal, Ivan Rakitic, Ter Stegen, Jordi Alba, Clément Lenglet and Gerard Piqué with inflation-adjusted fees and it would easily outstrip Liverpool’s £XI.)

In the league and Champions League they faced not one team as expensive as their own. In the domestic cups, aside from the League Cup final against Chelsea (whom they could only beat on penalties), City never played anyone with even half the £XI they themselves had.

Their FA Cup semi-final and final were against Watford, £62.7m, and Brighton, £51.1m; or about 10% of City’s £XI. In Europe, the most expensively assembled side City faced was almost certainly Spurs, whose £XI was 2.5 times cheaper than City’s. In one-off games you can lose to cheaper teams, as City did to Spurs, but City simply never faced a single club that could even compete with its £XI, as only Man United’s in the Premier League was close. (Carabao Cup: Oxford Utd, Fulham, Leicester, Burton Albion, Chelsea; FA Cup: Rotherham, Burnley, Newport County, Swansea, Brighton, Watford; UEFA Champions League: Lyon, Shakhtar, Hoffenheim, Schalke, Tottenham.)

City could only play what was in front of them, but their wealth dwarfed pretty much every team listed.

And none of this covers the nature of City’s ownership, and Abu Dhabi’s terrible human rights issues and warmongering. This piece by Ewan McKenna absolutely nails the issue.

Being a football fan can see us drawn into defending the indefensible. We’ve all backed things relating to our club we maybe wish we hadn’t (although when it comes to Hillsborough we backed the truth, in the face of spite and hatred, until it was proven that we were right; and yet still City fans and players sing about us always being the victims – which, again, is why that song is so offensive).

But you have to have some kind of tipping point where you say “you know what, this is just fucking wrong”. Idiots singing nasty songs is vile and unpleasant, but City’s owners are charged with something altogether more serious.

City fans will call Mo Salah a diver, and get red-faced about supposed Liverpool cheating, while ignoring Raheem Sterling or Bernardo Silva going down without contact. We are all hypocrites – because all clubs have players who have dived (indeed, Man City had one of the first in Francis Lee in the 1970s). Clubs have sponsors who are highly unlikeable companies that clearly don’t exist for the good of humanity. Clubs tap up other clubs’ players; everyone does it, going down the food chain.

But being directly funded by a sovereign state with terrible abuses to their name, and being accused of multiple levels of systemic large-scale financial cheating, is on a totally different scale to whether or not there was enough contact for Mo Salah to go down in the box against Newcastle or Bernardo Silva against West Ham.

Spurs and Liverpool have reached the Champions League final and secured top four spots (and Liverpool 97 points) by playing fair financially, and in the past, selling in order to improve their squads.

Unless other clubs do the same, it’s not exactly sport.