While he isn’t yet confirmed (and let’s hope his knees are in better shape than Nabil Fekir’s), it seems that Alisson Becker is to become Liverpool’s new goalkeeper, in what is a world record in un-inflated terms, but with the vital addition of inflation, only a third of what Juventus paid for Gianluigi Buffon 17 years ago.

This has been the summer of the goalkeeping howler. In case anyone thinks Loris Karius is some kind of blundering freak, he is guilty of just part of a bizarre and apparently ceaseless litany of goalkeeping errors that, to me, seem to date back to Bayern Munich’s Sven Ulreich, who made a remarkably unusual gaffe against Real Madrid (oh how Zinedine Zidane’s men benefited last season, eh?!), before Karius got in on the act, and then pretty much every top-class keeper at the World Cup suffered the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune (and/or brain farts).

Hugo Lloris is just the latest, trying to dribble past a player almost in his own 6-yard-box in a World Cup final, and escaping a panning by virtue of his side winning, in part due to very generous refereeing that allowed them to establish a 1st-half lead (oh how the admittedly immense Raphael Varane benefited last season, eh?!); following on from David de Gea letting in a really lame Cristiano Ronaldo shot (hit much less surely than the one from Gareth Bale that Karius fumbled) shortly before Spain crashed out; Manuel Neuer trying to dribble the ball (badly) down the wing; Fernando Muslera (with over 100 caps for Uruguay) losing the flight of a shot; and Willy Caballero kicking the ball straight to an opponent yards from goal.

Jürgen Klopp and his staff have noted how goalkeepers in England are never allowed to escape their mistakes, and how players, once judged, are often never reappraised. Players in all positions miskick the ball, get deceived by the flight or fail to see an opponent either creep up on them or steal in to intercept a pass. They all mishit shots at goal, and even the surest of players can miscontrol a ball or slip over (yawn). But if a keeper does it there’s a kind of extra hysteria around it. Obviously it becomes an issue when a keeper is making too many mistakes, but does this apply to Karius?

Well actually, as Andrew Beasley notes in his TTT article on Allison’s stats, Karius – the man who appears set to be replaced by Alisson – made just “two errors leading to shots in his 33 appearances in 2017/18, but both led to goals, and both were in the Champions League final. Ouch.”

Klopp was right; Karius is a very good keeper who was getting better and better until the biggest game of his life. But the baggage around the young German appears to be weighing him down. Karius is nowhere near as bad as people make out, but he was not (yet) an elite keeper, and his road to becoming an elite keeper was made tougher by events in Kiev.

Mistakes can (and often do) make us stronger in life, but as I noted in a recent piece, this is the era of the snide put-down, and of irate blame culture; and in the internet age, no one can escape their mistakes.

Now more than ever we are defined by our mistakes, and yet mistakes are the key factor in learning and improvement. However, the timing of the mistakes, the public nature of them and the cost of them can damn you; if the only time you crash your car is at 70mph into a wall, then you may not get the chance to ever learn from it.

But some psychologists and theorists say that what you are is gone; you are a different person in every single moment, always changing, and never as constant as you think you are. The past has gone – it no longer exists. But memories do. And digital video is around to show that even something in the past can forever be made present.

You can be an ex-alcoholic or an ex-criminal, but not an ex-murderer or an ex-rapist, even once you’ve served your time. Once no longer a virgin you can never be a virgin again. Some labels stick for life. Karius is not merely the sum of what happened in Kiev, but he will be defined by it. People will use it to make his life hell.

Promising keepers have seen their careers sidetracked by one major gaffe, although these keepers can often work their way back up in a lower-pressure environment. England perhaps has a greater obsession with goalkeeping mistakes, possibly tied to our need to pull others down and revel in their despair; American culture, while sometimes seen as nauseating, doesn’t seem to obsess about bringing stars down to earth, whether they merit it or not.

Karius had the spotlight of the world on him, and even when it was pointed out that he may have been suffering a concussion he was roundly ridiculed. An unseen medical ailment was somehow no excuse (which I can relate to, with an “invisible” illness), and yet a broken bone in his foot or hand or 37 stitches stapled into his head would have seen him labelled a hero had he carried on. (Although that leads to the issue of whether players should soldier on or leave the field if they don’t feel 100%, but obviously he didn’t realise he was concussed, if he was concussed, but concussions are complex.)

When he made mistakes in preseason, there were the japes about “is he concussed again?!”, but that doesn’t alter the fact that he’d had a good season until that possible concussion (and that a concussion could, and would, have affected his performance in the final), but that his confidence may have been hollowed out by being the man blamed for Liverpool losing in Kiev (when Sergio Ramos was the true villain of the piece, with vindictive acts of endangerment). He could have been concussed in Kiev, and now, as a result of the global scorn, reduced to a bag of nerves.

Remember, Karius made no mistakes leading to a goal (or even a shot at goal!) last season until just mere minutes after Ramos elbowed him in the temple; where the second error was also, in part, a consequence of the first. That suggests that the doctors may know what they’re talking about (but smartarses on Twitter obviously know more).

Upgrade

But let’s be clear: Alisson Becker – Brazil’s goalkeeper since the age of 22 – appears to have a better pedigree; already with 50% more international caps than Simon Mignolet and Karius combined (all three born in countries that are now major international sides). With Pepe Reina having grown stale and restless (and a little overweight) at Liverpool, perhaps the first prime-years elite keeper that John Achterberg has worked with. (More later on how I think Achterberg actually improved aspects of Mignolet and Karius’ games, but how errors can still happen. A coach can encourage confidence, but he cannot guarantee it. For example, in moments when greatest pressure is on, the best fielders in cricket can drop a simple catch.)

And with Becker, Liverpool are spending pretty big, but let’s not mistake this with the silly “buying the league” stuff I’ve been seeing. Liverpool still aren’t remotely close to having the cost of squads seen in Manchester; simply starting to close the gap a little.

Liverpool are now spending in line with increasing turnover and player sales; using the money received from the sale of Philippe Coutinho to attract top players. (Remember, in order for Liverpool to improve this summer it needed the loss of a world-class talent. If Man City want to sell Kevin de Bruyne or United sell de Gea, then they wouldn’t be buying success if they simply reinvested that money. It’s not financial doping in the way that Chelsea once did under Roman Abramovic.)

Liverpool’s squad cost and the best XI is still a long way behind the two Manchester clubs, albeit closing in fast on Chelsea’s, which used to be way ahead of the Reds’. Indeed, Chelsea appear to have lost out on Becker, as they try to fit within FFP and have to face life outside the Champions League yet again.

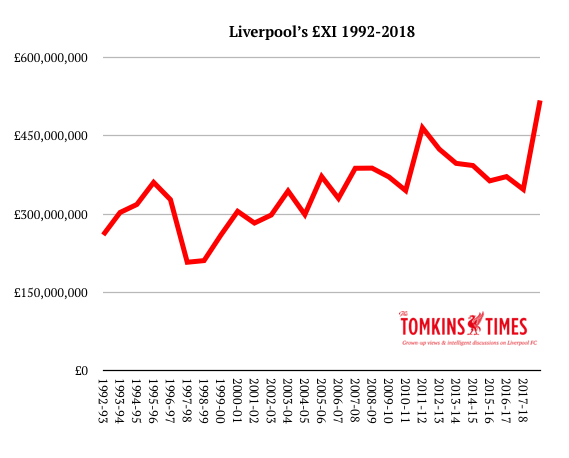

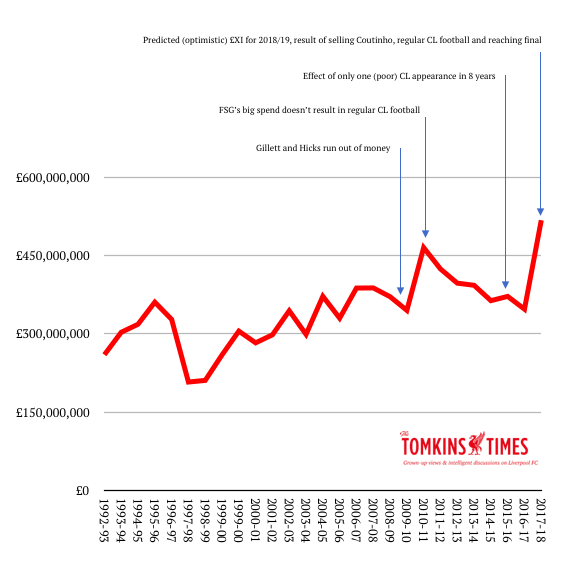

There’s a good chance that Liverpool will have the 3rd-highest £XI – the average cost of all 38 lineups adjusted for football inflation – in the league next season, and that hasn’t happened since 2008/09, just before Man City usurped the Reds. (And the Reds have been ranked 5th for quite a while now.) The higher your £XI, the greater your chances of a) finishing in the top four, and b) winning the title.

These were the £XIs last season:

– Man City: £753.1m

– Man Utd: £693.3m

– Chelsea: £494.7m

– Arsenal: £366.6m

– Liverpool: £347.4m

– Spurs: £295.4m

As you can see, Liverpool’s was only around half that of the Manchester clubs, and two-thirds of Chelsea’s.

To add Becker, Naby Keita and Fabinho to Liverpool’s XI would clearly make the £XI significantly more expensive next season; and also, Virgil van Dijk only played in about a third of the league games last season, so his £75m didn’t impact the average too highly. But of course, three players with transfer values would also need to be removed from the XI to accommodate them; and, in addition, the £XI, at the end of the season, is a reflection of who was fit and available, with cheap squad players often reducing the £XI.

There’s virtually no way Liverpool will end the season with an £XI of £500m+, because there’s almost no way all of the most expensive players will play all of the league games.

Liverpool have invested massively in the XI, relative to some other clubs; whereas other clubs have spent on hugely expensive 24-man squads.

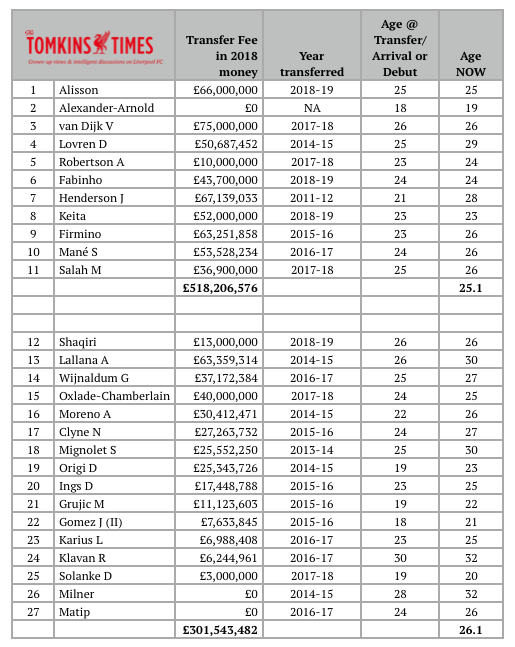

Liverpool’s “best” team has an £XI of £518.2m, but that’s not the costliest possible team. Adam Lallana’s inflated fee is £63m, so he’s £10m-£20m more expensive in 2018 money than Fabinho or Keita. Andy Robertson is £10m, but if Moreno plays, his inflated transfer fee works out at £30m.

Conversely, if Joel Matip or Joe Gomez play at centre-back instead of Dejan Lovren that instantly takes c.£50m out of the £XI, and if James Milner plays in midfield it takes out £40m-£67m depending on whom he replaces (£67m being Jordan Henderson’s 2011 fee adjusted for inflation. And as an aside on Henderson, remember how much £20m seemed in 2011? All the ridicule for that spending? While £67m in today’s money is not at all cheap, his value can be seen as he improves with age, leads the team, and looks set to reach 400 games for the Reds if he stays fit and at the club until the age of 31; at which point his fee will seem a veritable bargain, if it doesn’t already).

But where Liverpool still fall short is in the non-XI spending. This normal; Liverpool’s turnover is a fraction of Manchester United’s, so compromises must occur. Spending a lot on the XI, as Liverpool are doing, makes sense, but obviously leaves less spent on the squad (but where youngsters and bargains can be cannily deployed).

If you add together the 2018-money cost of the rest of the squad (players number 12-27), having listed the best XI, then it only totals 58% of the cost of the XI. Take out Simon Mignolet and Danny Ings, who seem set to leave, and it drops to 50%. And Alex Oxlade Chamberlain almost certainly won’t play this season, so it’s down to 45%. So while Liverpool have some excellent squad players, the spending has mostly gone into the XI; to spend more on squad players would have meant spending less on the XI, and that’s always a balancing act.

My guess is that the £XI will average out at about £450m this coming season, a jump of about £100m on last season’s £XI when converted to 2018 money. Anyway, here are some charts and tables showing those figures, below which the article continues.

Rivals

Right now there are six very appealing teams to lure top players to the Premier League (if not the elite “superstar” players, but that’s another issue. England is hoovering up a lot of the elite talent before it goes supernova, and tends to steer clear of the megastars).

Even Man City, with their league title, Champions League spot and Pep Guardiola have lost out with two of their last three major targets, with Alexis Sanchez going to Man United for the money (and maybe the greater global cachet) and Jorginho joining his mentor at Chelsea. Had this happened to Liverpool then everyone would go mad about the owners, or a lack of ambition, but it’s a fact that each player has a dozen or so main issues to weigh up when choosing a club.

Each club has a slightly different pull with the appeal of its manager, the players who can become teammates, the location (which can be important to some imports), the participation in the Champions League, the wages it can pay, and so on.

And right now, Liverpool can offer: the Champions League (for the cachet, and also allows for higher wages to be offered); world-class manager; world-class players (in particular, Mo Salah, in terms of current global icons); a thrilling brand of football that looks great fun to be part of; and, as usual, a famous stadium in which to play and a place in history as one of the most special clubs.

These latter points are fairly constant, although perceptions can change, and most current footballers weren’t even alive for the halcyon days of the club and the Kop. However, a certain mythology does prevail, which gets reinvigorated whenever the big European nights return.

You can add a special recent European pedigree (two finals in Klopp’s three seasons) to the sense of a club going places, that players must pick up on. Someone like Alisson will have felt the power of the Kop at its best.

However, let’s not pretend that Liverpool are now super-rich, and/or that FSG have just decided to become interested only now; not least when, relatively speaking, more was spent on players the season they took over, in a valiant effort to take the club back into the top four (having inherited a side near the foot of the table) but it didn’t work out. The intention was there, but while Luis Suarez and Jordan Henderson represented fantastic value for money, the huge fees spent on Andy Carroll (£121,785,131 in today’s money!) and Stewart Downing (£83,923,792), plus others, where a load of money was largely wasted, meant the improvement was only marginal.

FSG were not tightwads before, and they’re not super-generous now. They are doing what they said they’d do: make the club more profitable and put those profits back into the team, whilst improving the infrastructure where possible; all while working with the rules of FFP and sensible wages/turnover ratios. (Main Stand rebuild, further Anfield regeneration plans, and now the green light to build a state-of-the-art training complex at Kirkby.)

This summer is the result of steady building for three seasons under Jürgen Klopp and Michael Edwards, with the first reappearance in the Champions League for a second consecutive season in a decade, the first back-to-back 75+ points finishes in the league in a decade, and only the second time since 1985 that the Reds have made two European finals in three years. (I haven’t seen the latest UEFA coefficients, but Klopp must be getting it back up towards the days of Rafa Benítez, which can only help in terms of seeding.)

All this – along with the redevelopment of the Main Stand and more tellingly, the mega profit on Coutinho and the run to the 2018 Champions League final – is enabling a slow but undeniable return to the feel of Liverpool being a massive club on all fronts. (Even if there’s a long way to go to match the financial might of Man United, Man City, Bayern Munich, PSG, Barcelona and Real Madrid.)

For Liverpool to break the world record for two different positions in seven months says more about these three things than of any sudden super-wealth or “buying the league”: 1) inflation is not taken into account with such statements, given that Gianluigi Buffon would have cost Juventus £227m* in today’s money when inflation is taken into account, and using our Transfer Price Index football inflation, Rio Ferdinand cost Leeds £125.9m and Man United £197.9m**; 2) the positions Liverpool have struggled most with in the past few years (prior to 2018) were centre-back and goalkeeper, and so it’s worthy of paying a premium; and 3) most clubs spend too little on goalkeepers, in particular.

You can also add that Liverpool clearly underspent – due to smart buying – on Mo Salah, Roberto Firmino and Sadio Mané, so that in itself frees up money to spend in other areas.

And adjusted for inflation, Becker will rank only 3rd in the Premier League era for goalkeepers, with de Gea at £79.3m and Petr Cech at £67.7m, albeit both bought in their very early 20s and both superb value for money even at those prices.

Indeed, I don’t necessarily expect Becker to be as good as that pair have proved to be as signings for Man United and Chelsea respectively, but he doesn’t need to be; he just needs to be very, very good (and reliable), and not exceptional, to elevate this side to a new level.

(* Using only the inflation of the Premier League, and Italian inflation would have been different; ** Remember, these were either actual British transfer records, or close, and not too far away from the world records of the time. Alisson and Virgil van Dijk both cost about a third of what Neymar cost PSG last summer, and half of what Liverpool recouped for Coutinho. These are big buys, but the transfer market essentially doubled last summer with the big rise in the Premier League television income and the Neymar dick-swinging signing by PSG. Which is why inflation is so important to factor in, as the markets can change rapidly within just a few months. A few seasons ago £66m was an astronomical fee; now it’s merely medium-high.)

Okay, but why are goalkeepers so undervalued in financial terms? And what will Alisson bring Liverpool that his predecessors could not?

The final third of this article is for subscribers only.

[ttt-subscribe-article]