Note: This in-depth article (as TTT editor Chris Rowland can attest to) was written before the 7-0 demolition of Maribor, whose previous biggest home defeat was back in the 1990s, at just 4-0. I believe this means that Liverpool now hold the record away win for an English side in European Cup history, as well as the biggest-ever win in the Champions League format (Besiktas, 8-0). Maribor aren’t a great side, but they don’t usually get thumped like that.

Not that any sane fan couldn’t see that the Reds were due to thump someone soon, but it confirmed the randomness of finishing – which I again touch upon in this piece, and how, if you continue to create lots of chances, at some point they’ll start going in. And indeed, yesterday we published Andrew Beasley’s look at the Reds underlying stats compared with Jürgen Klopp’s Dortmund, and there was a lot to take heart from. Liverpool were exciting last season, but are actually creating more this time around.

Anyway, onto my article, which shows that, rather than Liverpool being worse this season, it’s just an insane run of games that has lowered the returns (allied to poor finishing).

Okay, this is a fact: this has been an insanely difficult start to the season for Liverpool. The information I will list below will show just how.

I want to put the difficult start into context. Which isn’t to say some performances or results couldn’t have been better, but unlike when Brendan Rodgers’ tenure was winding down (which itself came after a fairly poor season, and with growing internal unrest over transfer policy), this is not a clear and fatal downturn in the team’s belief. This is team playing well, and not taking its chances.

Remember, the Reds played better this season when drawing with Burnley at Anfield than last season when beating them. This is a team that played better against Man United than last year. The expected goals (xG) difference in both games showed a clear victory to Liverpool on the quality and number of chances created and conceded in these two games, as did the draw at Newcastle, and away at Spartak Moscow. All four draws were clear “points” victories to the Reds in boxing terms, but all ended equal. That’s the shitty-stick of football – you don’t always get what you deserve, and at the end it doesn’t go to a panel of judges if there’s no knockout.

The Reds aren’t taking their chances, and that’s a worry, but the team is actually creating more than last season, and therefore “playing” well. Adding a poacher – the standard response to a goal drought – will likely only make the movement less impressive and end up with less being created. (And even the best strikers have barren spells. For example, as of October 25th 2015, Harry Kane had just one league goal.)

In Mo Salah, Roberto Firmino, Sadio Mané and Philippe Coutinho, the Reds have the potential to get 60 goals from their front four. So far, we’ve rarely seen them together, and at times they’ve all missed good chances that they’d otherwise take. But striking often goes like that. Hence, Luis Suarez being labelled a wasteful attacker who’ll never score 20 league goals in a season for Liverpool, and so on.

On Saturday, Jürgen Klopp got the better of Jose Mourinho, whose plan would not have been to let Liverpool get into great positions, and then rely on the Reds missing the target or his goalkeeper pulling off an utterly unlikely save, even for de Gea. Mourinho got the draw he was after, but in this case, by luck rather than judgement. Coming to Anfield with Liverpool missing Mané and Adam Lallana, and with Joe Gomez making just the 11th top flight appearance of his career, as well as Coutinho – insanely – having played 86 minutes for Brazil on Wednesday, United were still outplayed. They were never going to be torn apart when getting so many men behind the ball, but this was not a Mourinho defensive masterclass. Either United weren’t playing well, or Liverpool stopped them having an easy time of it.

The latest stat, which I asked if TTT and LFCHistory stalwart Graeme Riley knew the answer to (knowing he would!) is that Liverpool are in a run of six away games from seven fixtures. On just eleven occasions since 1903 (NINETEEN HUNDRED AND THREE!) has such a run occurred. It has happened in just ten different seasons since the club was formed in 1892. Therefore, this is a once-in-ten-to-fifteen-years anomaly. Once Liverpool have gone to Spurs next week, it will signal an end to an ultra-rare level of fixture difficulty; and, as I will come onto, that includes factors other than just the games being away.

On average you take fewer points away from home. But also, look at the quality of the opposition the Reds have faced home and away. As the league table stands, after next weekend – post-Spurs – the Reds will have played seven of the top nine teams (and one of the current top nine is Liverpool, and they can’t play themselves). The only two teams in the bottom 11 the Reds have played are Crystal Palace, the club’s usual bogey side, and Leicester (away), another tough game against a team unlikely to stay down there. Yes, I’ve made some of these points before, but it’s worth going through the whole set of circumstances, one after the other – and then looking back at previous seasons – to get a fuller picture and get away from the hysterical zooming in on doom.

Look at the extra two Champions League qualifiers … against Balkan minnows, Macedonian oddballs, Kazakhstani never-heard-of-thems? No, two games against Hoffenheim, who were top four in Germany last season and are once again top four in Germany. Liverpool were the only one of England’s five representatives to have to play these two extra games – which is the downside of finishing 4th. Obviously we’re all happy to just be in there, but let’s not let that happiness mask the added difficulty. (Arsenal also didn’t have to play qualifiers for the Europa League. So Liverpool were the only one of the Big Six to play two extra games.)

Okay, so, the first group game, that was a ‘gimme’, right? Yeah, Sevilla, top four in Spain last season, currently top four in Spain again this season, and winner of three Europa Leagues in the last handful of seasons. The group itself is not the toughest, but the opening fixtures weren’t the kindest.

Big Six

So, how about the other five members of the Big Six? Liverpool will have played four by next weekend; Man United, by contrast, just one. One!

And United have a bigger, costlier squad to deal with such difficulties, especially early in the season when fighting on three fronts, including Europe. Except, they’ve been handed a free pass. Which is not to say there’s some kind of fixture list conspiracy, or any underhandedness. Just that, this season, the Reds got royally shafted by a series of fixture list computers.

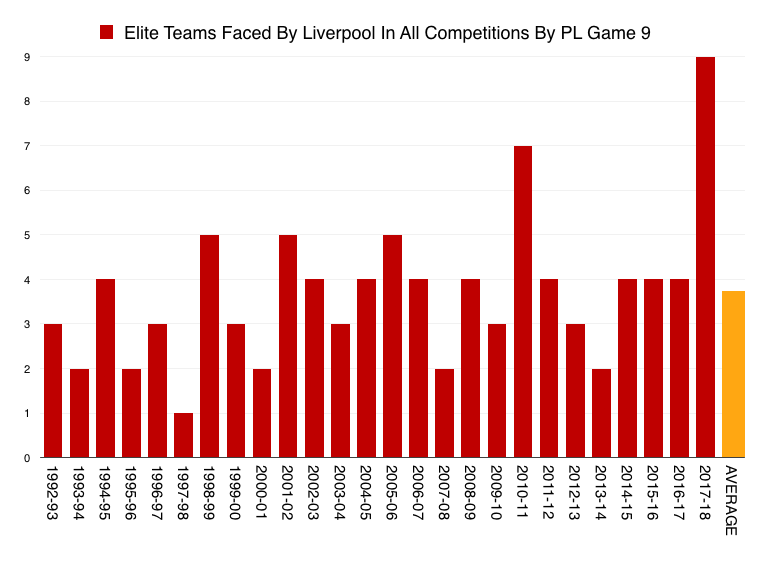

As I said a few weeks ago, by game nine you would normally have expected to play two such fixtures, with a third by game 12; one roughly every four games. Yet Liverpool are currently running at twice the normal difficulty frequency on these games. Yes, that makes the remaining 29 games easier on paper, after visiting Spurs at Wembley, but the damage can be done early in a season, when you’re left playing catch-up, and under additional pressure.

Game nine is when Liverpool get the last of the really difficult league games (Spurs) out of the way (for a while), but also, exactly a quarter of a season. Now, there are other ways to chop these figures up – the first three league games, for instance, would show far tougher starts for Liverpool in recent years than this season. But it’s also easier to get over a tough three-game start than a tough nine-game start. And, if you still think a nine-game study is a random cut-off point, it’s more-or-less where we are right now.

Indeed, I’ve gone back through the last eight seasons, and only twice have four league games against the best sides appeared so quickly in the Reds’ Premier League schedule: last season (so Klopp was unlucky there too), and in Roy Hodgson’s brief tenure – both times all four were played within the first eight games, as opposed to the nine this season.

This period dating back to 2010 includes seasons where the Reds went an incredible sixteen and eighteen games before having played four of “Big Six” fixtures (both times under Brendan Rodgers); while the average duration of Liverpool playing four big rivals is between 12-13 games from the start of the season – still more frequent than one every 3.8 games, which is the season of 38 divided by the ten fixtures.

It seems that the Premier League like to schedule its European teams to play each other while they are all in the competition, so they are all, in a way, equally disadvantaged. But that doesn’t really explain United having such an easy start.

It’s a small data set, but we can say that the worst start made by Liverpool in the eight-year period is that made by Hodgson’s Reds, which was the joint-toughest in terms of big-name opposition within the first eight or nine games; although – it’s worth remembering – the Reds only had the Europa League to contend with at the same time, so it wasn’t as complicated as this is right now.

Hodgson’s League Cup game was also a soft one, at home to fourth-tier Northampton, although it was still lost. The non-Premier League games were against Rabotnicki, Trabzonspor, Steaua Bucharest, Utrecht and Northampton, with only Napoli presenting any type of cup challenge. The 9th league game was Wigan Athletic, but the other early league games included West Bromwich Albion, Sunderland, Blackpool and Blackburn Rovers – so plenty of “easy” games (on paper) too. (And again, this is a season before Man City won the league for the first time in the modern era. They weren’t yet a “superpower”.)

But in Hodgson’s defence (a rare statement for me), the 9th league game – Wigan – was the Reds’ 21st game of the season; although that was up to mid-November. The Reds will be on fifteen games this season after the visit to Spurs, all by mid-to-late October. (Weirdly, looking back, in 1993/94, the first eight games of the season were all in the league, with the 9th league match arriving in September, three days after a certain scampish young striker made his debut in the League Cup.)

And the easiest start in the past eight years? Well, that just happens to be 2013/14, when the Reds faced their fourth such opponent by game eighteen – halfway through the season – and had no European football at all; the club’s 2nd-best season in 27 years for points. Brendan Rodgers oversaw a great season, but he got a bit lucky with the start.

While we talk a lot about the myth of momentum on this site, what I do believe is that bad results can set a negative tone for a season, and the tougher the games you play, the more likely you are to see some setbacks. Equally, while momentum comes and goes – you still lose games when full of confidence, and good form can quickly turn bad (and vice versa) – good runs become self-supporting; albeit winning three games in a row will not suddenly turn an average team into champions (although did Leicester do this, I wonder?).

Liverpool had a good start last season despite four such fixtures in the first eight games, including a greater number away from Anfield overall due to the Main Stand expansion; but of course, there was no Europe and no testing cup football in between (the League Cup threw up a comfortable trip to Burton Albion, followed by another lower-division opponent in Derby County). Exactly a year ago as of the time of writing, Liverpool had only played nine games in all competitions.

To be clear, this piece is more about the difficulty of the league fixtures allied to the difficulty of the additional fixtures; it’s about the toll the cumulative “pile up” takes.

So, to recap, Liverpool’s worst season in the past eight campaigns (the Hodgson one that was redeemed later by Kenny Dalglish) had the toughest start in terms of “big games” (although obviously it got no better under Roy when the games got easier on paper); and the Reds’ best season in that same period had the easiest start using the same measure. Other factors no doubt played vital parts, as they do with the complexities of any given season (it’s never about one thing, just as 2013/14 was not just about Suarez and 2014/15 was not just about losing Suarez) but it’s an interesting link all the same.

Incidentally, without having checked Manchester United’s prior seasons, the fact that they waited eight games to play a Big Six rival this season contrasts starkly with the Reds who, aside from waiting until game six in 2011/12, have played a major rival within the first three games every other season since 2010, and in that time average under three games before they face their first super-firm test. To get to eight seems really odd, if not necessarily fishy (he says, for legal reasons).

Euro Club Index and Opposition Quality In All Competitions

Okay, so it is a tougher than normal first nine Premier League games. That should seem clear.

But the addition of tough cup games can really tip a team over the edge. I always find late February/early March interesting, as it’s when the Champions League resumes and our big clubs often end up with four tough games in ten days, or something similar. Seasons often come apart right then. That said, in Liverpool’s case, the problem under Klopp in his previous two winters has been the ten or eleven games within just 30-33 days from late December to late January, in part due to the League Cup. (Which won’t be a problem this season.)

Indeed, look at the recent League Cup game away at 2016 champions Leicester for another example of Liverpool drawing the short straw – hardly comparable to the games any of the other big Premier League teams got. Spurs were at home to Barnsley. Man United were at home to Burton Albion. Chelsea were at home to Nottingham Forest. All three of these games were home to second-tier opposition. Arsenal had it easier still, and faced third-tier Doncaster at the Emirates. Manchester City away at West Brom was the only comparable fixture to Liverpool’s. Aside from Man City, all the other big clubs essentially got a free midweek to field their kids.

But then Guardiola’s thrilling City didn’t have a Champions League game as difficult as Sevilla to open with, and by league game nine will have faced just two of the Big Six, half as many as Liverpool. That said, they look capable of beating anyone right now, but sometimes it’s just the sheer weight of numerous tough games in a short period of time that cause teams to crack, even if only for a game or two.

As of next week, the Reds will have played five of the current top 16 teams in the Euro Club Index. FIVE!

And also after the visit to Spurs, it will be a total of nine matches against teams in the Euro Club Index top 50. Six of the nine will have been away from home. So, again, this is unusually difficult.

And while, cup matches aside, you have to play everyone twice over 38 games, the schedule determines, to some degree, how well you start. For instance, part of Crystal Palace’s problem has been the fixtures handed to them. No one is beating Liverpool this season when they have all eleven men on the pitch.

And in Liverpool’s case, having so many extra-demanding games limits the ability to play a full-tempo hard-pressing game. Perhaps this is why the pressing statistics have not been as impressive so far this season. You have to be able to deal with games every three or four days, but if they are almost always tough games, it is more sapping.

Toughest Ever?

I would go so far as to say that, based on my research, this start – up to and including Spurs next weekend – is the toughest start to a season Liverpool have had since the Premier League era began in 1992.

And given that the Reds weren’t in Europe between 1985 and 1991, you can take it back at least to Joe Fagan’s time.

Now, what constitutes a super-tough opponent has changed over the years, in terms of particular teams and their strengths. For example, if you drew Nottingham Forest in the cup in 2017, you’re not playing Brian Clough’s champions of Europe anymore; nor even the UEFA Cup-qualifiers of the 1990s. You’re playing a second-tier side. Equally, in 1993, Chelsea were pretty rubbish.

For the purposes of this study, I have decided upon the following definition as to a really tough opponent: a club that finished top four in the German, Spanish, Italian or English top division the season before, and/or reached the Champions League quarter-finals. Also, all members of the current Big Six in England (so Arsenal aren’t excluded on the basis of finishing 5th), and all members of the Big Four where appropriate beforehand. Plus, given the nature of the game, I’ll include the Merseyside derby, even if Everton’s quality has fluctuated violently over the years (although that doesn’t affect this year’s figures).

Manchester City only really became a serious threat from 2010 onwards, and Spurs also only became something of a force around that same time, when they qualified for the Champions League under Harry Redknapp; albeit falling away a few years later, only to be revived under Mauricio Pochettino. So were Spurs an elite rival in, say, 2013? For now, let’s say yes, especially as no one unusual grabbed a Champions League spot from 2005 until 2016, when Leicester smashed their way in. But again, this only helps Klopp’s predecessors in terms of assessment.

Conversely, Arsenal were much stronger from 1997-2005 than they have been since. But a decade ago there was a Big Four, not a Big Six. Last season was, if memory serves, the first time in a 38-game season that a team finished with 75 points and ended up outside the top four, and Man United finished 6th but with two cups. So these six are all clearly strong sides. Arsenal actually improved their points tally last season, but still finished lower.

Of course, it’s hard to prove that the top six now is way stronger than the top six of, say, 2003 or 1995, or 1999. In 2001, Leeds United were a force (before the bubble burst), as were, to a lesser degree, Newcastle. Go back a few more years, and Newcastle were the 2nd-best team in England, and for a season, Blackburn were the best. So there will always have been tough league games earlier in those historical seasons.

However, there have only been just over a handful of occasions where Liverpool have had the relative nightmare of a Champions League qualifier. So the years without those games instantly limits the number of tough games at the start of the season. There have also been tough Charity/Community Shield matches, although do they count? I think not, unless against Man United. Plus there’s the European Super Cup, which is more meaningful, but that always meant a league fixture was postponed for the game to take place in Monaco.

So let’s work back, and examine all of these starts to seasons beyond the eight already touched upon, focusing on the first quarter of each campaign.

In 2009/10 – when the wheels came off for Benítez – there was no qualifying round of the Champions League, after the excellent previous season. The first nine league games included just two extra-tough fixtures, with the others Stoke City, Aston Villa, Bolton Wanderers, Burnley, West Ham United, Hull City and Sunderland. Now, Stoke weren’t easy back then, but these were not elite opponents. The same applies to Debrecen in the Champions League. Spurs were on the rise, as were Fiorentina, and Chelsea were the eventual Premier League champions. Liverpool’s problem that season was not the fixture list, but a club being pulled apart by internal strife and terrible owners.

In 2008/09, the best points tally the Reds have racked up since the halcyon years – 86, when finishing 2nd – saw the Reds play Standard Liege in the qualifying play-off; a decent if unspectacular opponent. The first nine league games included Manchester United (game four) and Chelsea (game nine), as well as Everton away, at a time when they better than they are now but not as good as they were, briefly, in 2005.

But no Arsenal. The early league games included Sunderland, Middlesbrough, Wigan, Portsmouth and – admittedly a pretty good side back then – Aston Villa (but they were never a Champions League side, unlike Leeds and Newcastle; and indeed, even Everton nearly were too, but for the awful draw of Villarreal in the qualifier). Lowly Crewe Alexandra were faced by the Reds in 2008/09 in the League Cup. The Champions League group included Atletico Madrid, so that’s a Spanish top four team (i.e. elite), even if Atleti were not the force they went on to become under Diego Simeone. Marseille and PSV Eindhoven made for a pretty tough group – tougher than the current one the Reds face – but the league games were generally much easier, the League Cup game was easier, and the qualifier was easier. (And Liverpool were in the fifth year of a manager’s project, and had a ton of European pedigree by then.)

The qualifying game a season earlier was Toulouse – a top four French side. But that league was not as strong as the current German and Spanish leagues, and even the French league itself is probably better now. I’m loath to bracket Toulouse with the top four teams from Germany, Italy and Spain. I did at least consider including them as an elite side, but looking at the French league table that season, they finished 17th, two points above the relegation zone.

The League Cup game was away to a Premier League side, at Reading (Fernando Torres bagged his first hat-trick), and by the time of the 9th league game, the Reds had faced Porto and Marseille in the group stages of the Champions League. However, by the time of the 9th league game (Everton away), the Reds hadn’t played either Man United or Arsenal. Six of the nine Premier League games were against Aston Villa, Sunderland, Derby County, Portsmouth, Birmingham City and Wigan Athletic. So, a tough start in Europe, and a tough League Cup game, but not a tough Premier League start. So that still contrasts with 2017/18. Overall, far fewer tough games.

The year before that, 2006/07, saw Maccabi Haifa faced in the play-off. Again, not an elite opponent. Yet again there was an early-season trip to Goodison Park, but only Chelsea and Man United of the elite teams were faced by league match nine; Arsenal arriving on fixture 12. The group stages in Europe involved PSV Eindhoven, Galatasaray and Bordeaux – all good sides, but harder to assess as they were all from weaker leagues. The League Cup game was against Premier League new boys Reading, at Anfield; so a bit different than being away to the 2016 Premier League champions and 2017 Champions League quarter-finalists Leicester. (Who may still not be an amazing team in so many ways, but are rarely easy to play.)

In 2005/06, the Reds faced three qualifying rounds for the Champions League, as the hitherto ridiculous rules had to be re-written to allow Rafa Benítez’s men to defend their title. Those six games were all easy enough on paper, with CSKA Sofia the final, and toughest, play-off opponent. The glory of Istanbul also meant playing CSKA Moscow in the European Super Cup. So this was a bit of a mad start, in terms of the sheer number of games – 11 cup games played by the time the 9th league game came around, making for one less than in 2010/11.

However, the League Cup game was 2nd-tier Crystal Palace away (the kids duly played, and lost), and the early league games included Chelsea and Man United (no Arsenal), but the other fixtures included Middlesbrough, Sunderland, Birmingham City, Blackburn Rovers, Fulham and West Ham United.

That said, Chelsea were also played in the Champions League group, and by the time the 9th league game had been completed, Liverpool had played five games in all competitions against ‘elite’ opposition, if we say that Real Betis qualify as top-four Spaniards. But that’s still nowhere near as many as this season.

And this was, famously, a poor start from Liverpool (Champions of Europe!), with lots of disgruntled fans (I received their angry emails), before Benítez’s men turned on the style from the start of November, keeping a staggering eleven clean sheets in a row. But this was also a team that months earlier let in four at home to Chelsea, two away at Birmingham, two at Fulham and two in losing to Palace in the League Cup. So that shows how form can change after the end of a crazy schedule (and indeed, the good run came to an end at the World Club Championship, as the routine got disrupted again).

Benítez’s first season, 2004/05, saw minnows Grazer AK faced in the qualifier. There was no League Cup game until after league match 10. Manchester United and Chelsea were faced within the first seven Premier League games, but Arsenal were not met until the winter. In Europe, Monaco were then an elite side (beaten finalists the year before, so better than a normal French side), and Deportivo La Coruna were top-four Spaniards. (Olympiacos were merely okay.) So that’s four matches against elite opposition by Premier League game nine.

In 2002/03, Gérard Houllier’s second and final Champions League campaign, Arsenal were faced in the Community Shield, but that was hardly a massive game. Still, I’ll include it anyway. And having finished 2nd the season before, the Reds faced no qualifying play-offs for the Champions League. Basel and Spartak Moscow were not elite European sides by any stretch of the imagination, but of course, Rafa Benítez’s Valencia, the reigning Spanish champions, were the other team in the group, and they clearly were. If including the Community Shield, that’s still only four elite teams faced by league game nine: Arsenal, Newcastle United, Valencia and Chelsea (and even then, Newcastle and Chelsea weren’t that great at the time.)

In 2001/02 Liverpool qualified for Europe’s top competition, but it was also the first time in its new guise of the Champions League; so, the first top-tier European outing for Liverpool since 1985 and Heysel. (And so, in my trawling back, the last time in “the modern era” that the season could have included European elite opposition and Champions League qualifiers, so there’s little point going back further; although I have still looked at the data, I just won’t detail it all.) Now, the qualifier was about as easy as it gets – FC Haka of Finland, beaten 9-1 on aggregate.

However, Manchester United were faced in the Community Shield, and unlike Arsenal a year later, that’s probably never a “friendly”. Then came the mighty Bayern Munich, champions of Europe, in the Super Cup. So that’s two elite opponents before the league season even really got started. However, the Champions League group included Boavista and Dynamo Kiev, neither of whom were anything special. Borussia Dortmund would go on to win the German league that year, although they finished below Boavista in the Champions League group.

However, if we include Leeds and Newcastle as elite sides (they’d finished top four in the Premier League around that time, as had Chelsea, before the Abramovic billions), then that’s still only five matches against top opposition, up to and including league match nine. And that’s me being very generous with the assessments. (However, by league match 14, the Reds had also faced Manchester United, Barcelona and Roma, the latter two in the crazy second group stage of the bloated Champions League.)

In all these examinations of seasons from 2001 to 2017, I can only find a maximum of seven super-tough games by this stage of the season, compared to the nine this year. But aside from that seven, the next-highest is just five. Go back further, to 1992, and the range is between one and five.

The League Cup matches weren’t even appearing for the Reds until after PL game 10. And of course, prior to 2001 – all the way back to 1985 – there was only the UEFA Cup, at best, for Liverpool, and in those cases, excellent teams like Barcelona and Roma were only really faced later on in the season.

In the Premier League era, the Reds average under four of these ultra-tough tests by the time league game nine is played. This season it’s nine. Even if we discount the two games against Leicester, it’s still seven – the joint toughest schedule in 25 years. (Leicester may be debatable given how they’ve fallen, but I include Newcastle and Leeds in earlier years, and they actually achieved less.)

So, this all means that the fixtures this season are something of an outlier; a tough, tough set of games. Whenever the Reds have had a start anywhere remotely like it, results have tended to suffer.

So in a sense, so far this season it’s a staggering NINE games against recent Champions League participants and/or top four Spanish/German sides before the end of October. And that will be from just 15 matches played in all competitions! When you look for supposedly easier games in that list, there’s only once been two in a row – Newcastle and Spartak Moscow – but both away from home. This week Liverpool get an easier fixture (on paper) against Maribor, but it’s sandwiched between Man United and Spurs!

And then, of course, there’s the run of six away games in seven, which, as noted earlier, is the kind that should happen once in any player’s career. (Or once every fifteen years.)

This start has been unprecedented in its toughness, spread across various competitions. Add the unsettling Philippe Coutinho saga, the ludicrous Mané sending off (compared to what others get away with), the baffling lack of a league penalty since the opening game, and the various injuries, and it’s clouded the fact that Liverpool are actually a really good team.

And let me be clear: all of this doesn’t mean Liverpool will come out of this crazy schedule after the Spurs match in perfect shape and just click into gear once things get easier on paper. But it has to improve the odds of it happening.

So whatever happens this week, once Spurs is out the way there’s a more normal distribution of fixtures; indeed, there logically then has to be easier runs of games coming up. And with no League Cup semi-finals in January (after two last season and two the season before), there’s more space in the winter to get through with more energy intact.

Hang in there, it should get better.