By Paul Tomkins, with additional research by Daniel Rhodes and Andrew Beasley. Interactive graphics by Robert Radburn.

When he’s struggling for form, fans often wonder why Emre Can plays. “He slows the game down,” they say. At the same time, fans will also bemoan Liverpool’s vulnerability against ‘weaker’ teams.

But here’s the crux of this piece, most of which was written before Can won the game for the Reds against Burnley: I’d argue that the weaker sides just happen to be the more physical. What are perceived as “weaker” teams are actually far taller, stronger and heavier. Physically, they are stronger teams.

People will say it’s a mental issue, that Liverpool can’t beat the “easy” teams because they are too casual; but the easy teams are mostly the hard teams. At times it’s bantamweights versus heavyweights. I noted this a few weeks ago in a piece that was also about Arsenal. But in this piece I take the notion and run with it, researching deeper into the clash of styles.

That’s the great oddity about our game; it adds to the drama, and the fun, to have such a mix of approaches, but few inexpensive sides and small clubs look to pass their way to success in England’s top league. The English way of overcoming the odds is usually the longer ball, the cross, the set-piece. It’s about height, strength, brawn.

Statistically, the “little” clubs are clearly the bigger units, and they make life tough for you (as is their right, within the laws of the game), and then it’s down to you to try and match their aggression and deploy your quality. But it’s hard to do that every single game. It’s physically demanding, if they are bigger and heavier. Added to that, the smaller clubs usually play fewer cup games (especially since eschewing the cups to help retain their Premier League status), and so will tend to have more freshness. This doesn’t mean that clubs with other styles haven’t troubled Liverpool, with Southampton leaping out. But the smaller clubs who are bigger teams have caused more panic.

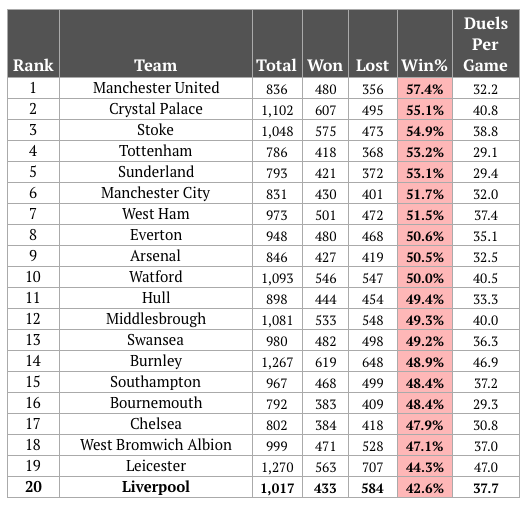

The most aerial duels this season have been contested by Leicester, Burnley, Crystal Palace and Watford; the only surprise is that Tony Pulis’ West Brom rank 10th. Liverpool have been involved in far more aerial duels than any of the other ‘big six’, yet aren’t a direct side. Surely this is evidence of teams trying to get at the Reds in the air?

In the first five minutes today, Burnley hit long high ball after long high ball, and when Ragnar Klavan and Joel Matip were starting to get giddy, the visitors started slipping through-balls down the sides, just like Leicester did. They resorted to long-throws, just like Leicester did. And they spent the second half with their keeper taking free-kicks on the halfway line. It was an orgy of “into the mixer”. Having researched which Liverpool players were good in the air and which were not (and by this I mean winning headers, not heading technique), everything Klopp did make sense to me – even if it didn’t to plenty of others.

Emre Can has become the centre-backs’ aerial protector; doing it well against Olivier Giroud last week. But an issue is that the centre-backs can’t deal with enough in the air, Dejan Lovren aside. Against Burnley, Can must have won ten aerial duels; I lost count at five.

Right now, Can has to play, because the squad is too small – in terms of height, for certain. When Klopp talked about adding five or six players this summer, more strength, size and power looks essential.

I talked about size quite a lot last season – particularly when it comes to a lack of height. And it was addressed by Jürgen Klopp, Michael Edwards and co. in the two transfer windows of 2016, to some degree, although fate has conspired to muddy the waters a little.

Weak = Strong, Strong = Weak

Last year I wrote that Liverpool had to get bigger and stronger, unless they got markedly better. That remains a key statement. This will always be my view on the issue: size is important, unless you can play football so good that it overcomes all barriers.

The first half of the season was a fascinating insight into the latter approach: Liverpool remained a very small team (smaller even than last season), but they dictated the type of game it was. Confidence, freshness in the autumn after a good preseason, and the injection of Sadio Mané’s pace and skill, meant that even though Klopp and co. had brought in the giant Joel Matip (who only came into the side after a few games) and the huge-for-his-age Marko Grujic, it was the smaller players who helped make Liverpool so hard to live with.

No one could keep tracks on Mané, Coutinho, Wijnaldum and Lallana, plus the “average-sized” Firmino (albeit below average height for a no.9); while the two 5’9” full-backs – Milner and Clyne – had a great few months making use of the space the fluid system gave them. Then, of course, it came to a crashing halt, with Coutinho injured, Mané away, and Lallana, Clyne and Milner losing form (and with Coutinho returning very rusty), and with everyone experiencing a dip in the gruelling 11-game period from Boxing Day to January 31st.

The season effectively switched. Liverpool played too many cup games after the busy festive period, and with injuries and absentees, lost their mojo. Suddenly unable to force their style onto the opposition – not fresh enough to dictate the games, and not quite enough quality in reserve (especially given the injuries) to freshen things up too much – the Reds were on the ropes; and their weaknesses came to the fore. In some games they were clearly bullied.

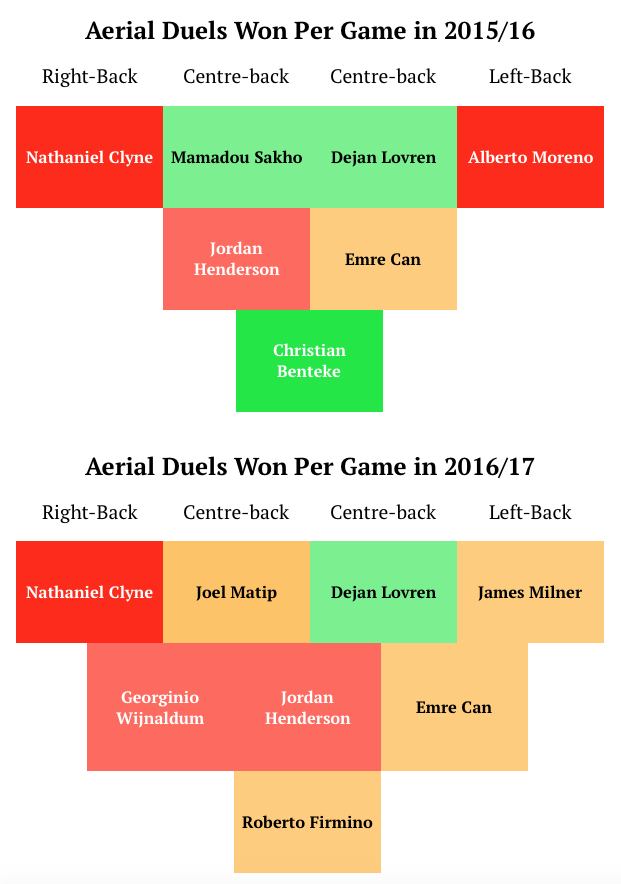

Last summer Liverpool looked to add quality (Mané, Wijnaldum) and physicality (Matip, Grujic and, to a lesser extent, Klavan). However, for all their height, Matip, Grujic and Klavan are actually doing far worse in the air (as I will go on to show) than three of the players they effectively replaced: Skrtel, Sakho and Benteke; plus, of course, the loss of Benteke – while understandable, given his lack of movement and general confused air (a strong man whose price tag weighed heavy) – meant an even greater weakness at defending set-pieces, irrespective of attacking them.

As you can see below, Liverpool are the shortest team in the Premier League, and the second-lightest. The Reds are grouped with Man City and Arsenal – two other teams said to be lightweight – whilst at the other extreme, Watford almost need a graph of their own. (Bottom left = tricky, technical; top right equals brutal bastardry.)

And while there are obviously other elements at work when it comes to results – tactics on the day; finishing/chances taken or not taken; goalkeeping errors and/or remarkable saves; refereeing mistakes, for and against; key players present or absent; too little time to prepare and recover*, etc. – I believe that there’s strong factual evidence to suggest that, just like Liverpool against Wimbledon in the 1980s, the “bullies” can sometimes have their day through sheer brute force.

(*Liverpool’s results under Klopp with four or more days to prepare are significantly better than with three or less – which I guess is the case with most teams; everyone needs some freshness. Obviously a two-week rest may be too much.)

Back in the 1980s, Kenny Dalglish often used to leave out Peter Beardsley for clashes against the giants of Wimbledon, even though he was one of the best players in what was then the best team in the league. A certain pragmatism was in the approach of the Scot.

Both Jürgen Klopp and Pep Guardiola – still relatively new to England – have expressed surprise at just how many balls are contested aerially in England. They just happen to possess – in a large part through inheritance – the shortest and second-shortest teams in the Premier League; and the lightest, and second-lightest.

(Last year I looked back at Klopp’s Dortmund teams, and they were usually a much taller, stronger side than his Liverpool XIs have been so far. Dortmund had smaller, technical players, but they had those hard-to-find big, strong and talented players like Mats Hummels and Robert Lewandowski; while İlkay Gündoğan and Marco Reus were creative and yet also just a shade under 6ft. Marcel Schmelzer was a 5’11” full-back, Łukasz Piszczek a 6’1” right-back.)

These great managers know their teams have to be quicker to the second ball; but you can’t always be – sometimes it falls to an opponent. Equally, these managers want their players to stop the crosses, and the high balls that put them under pressure, but that can’t always be done. These are areas where the shorter team must do their best, but not everything can be stopped at source, and not every second ball will bounce your way; and on the law of averages, bigger players will win more headers. But for a panicked shot, Burnley could have equalised in injury time from another long throw.

Indeed, below are the statistics on the average size of Premier League players and the number of aerial duels won per game over the past two seasons by players of different heights.

Making the Case that Liverpool Aren’t Necessarily Weak Mentally

The team with the worst aerial-duel success rate in the Premier League? Liverpool. People say the team are weak mentally, but they’ve come back from 1-0 down more often than anyone else in the Premier League this season. The worry, for me, is that physically it can be like boys against men at times. (Or in Ben Woodburn’s case, literally boys against men, although he played with the composure of a 27-year-old today.)

As an area I’d hoped would be improved upon, Liverpool have actually fallen from just below-mid-table on this metric in 2015/16 to last place. (Whilst improving as a team overall, I hasten to add, to bring us back to the central conundrum.)

Liverpool don’t contest an alarmingly high number of aerial duels, because it’s not in the Reds’ interest, although winning a lot of corners, and throwing in a few crosses in the way that every team does (sometimes in desperation), means duels still get created that way.

Equally, it’s of the opposition’s interest to create aerial duels against Klopp’s team; we’ve seen them do so. Just watch the Burnley match again, and count them. (Although all the stats in this piece are correct as of kick off today.)

So the number of aerial duels the team has contested so far this season (c.1,000) is right in the middle of the spectrum; c.200 more than Spurs and Man United, and 200 fewer than Leicester and Burnley.

But as the shortest side, Liverpool – somewhat predictably – have the worst win % for aerial duels; as I’d hinted at last season, and now backed up with even more data here.

(Last season I suggested that smaller players would, on average, win fewer headers, and people said things like “but what about players like Tim Cahill?”. But there’s a difference between attacking a ball with a good run/leap and defending set-pieces, for example. Gini Wijnaldum is great at attacking crosses, but has only a 51% success rate in aerial duels. And he’s one of the few Liverpool players to do better in the air than is expected for his height. See the earlier graphic.)

Weirdly, the team with the worst success rate in aerial duels last season was Leicester, the champions, at just 43%.

However, the number of aerial duels contested was off the charts, at 1,660, over 200 more than anyone else.

They weren’t an especially tall team on average, but they were aggressive, and they had two tall and very strong centre-backs, as well as a very tall left-back (Christian Fuchs), plus a tall striking option in Leonardo Ulloa, who in certain games was hit like crazy. Their right-back, Danny Simpson, at 5’10” is taller than any of Liverpool’s three main full-backs (Milner, Moreno and Clyne), and averages roughly five times as many aerial duels won than either Moreno and Clyne, and is a fraction above Milner in both quantity and also percentage.

(As an aside here, the Leicester defender with the most aerial wins per game this season is a certain young Ben Chilwell, whom Liverpool were after last season. At just 5’10”, it’s from only 300 minutes of football, so the sample is small. Still, he has won more than three duels per game, at a 69% success rate – which is better than most centre-backs, and better than any Liverpool player this season. When we scouted him on TTT last summer, the verdict using the professional scouting video evidence we shared was that he looks a great all-round talent for his age. Alas, he’s not fancy enough for some fans.)

Was Leicester’s crazy quantity of aerial duels last season because they put in a lot of crosses/long balls but also faced a lot of crosses, as they retreated into their famous block? Even if Wes Morgan and Robert Huth weren’t winning all the headers (exactly the same as Liverpool’s, in terms of quantity per central defender, and not a particularly remarkable win%), their tall back four made scoring against their packed defence pretty tough. Also, Jamie Vardy won close to three aerial duels per game last season – the equivalent of someone five inches taller, although it was from contesting a very high number.

So is this the “percentage game” that was partly behind their success: the hope of Vardy winning a crucial few headers, out of a large supply? Interestingly, Leicester have also contested the most aerial duels this season, with largely the opposite results, even though Vardy continues to win headers.

Not many of Liverpool’s players from the past two seasons have been particularly above average in the air for their height. However, some are/were. Christian Benteke is the obvious example, leading the whole league this season in aerial duels won, at 9.3 (at a win% of 59%), but even at ‘just’ 4.4 won per game for Liverpool, he was still above the average for his height and his position. No one else, this season or last, has averaged more than 3.4 wins per game.

Lucas Leiva is well above average in the air for his height, but not for his position (if that position is centre-back; if it’s central midfield, then he’s also well above for that). However, look at the role he performed when he came on today, to shiel the back four from the long-ball assault.

Again, Georginio Wijnaldum is well above average for his height, but a fraction under the average for a central midfielder. Jordan Henderson is a fraction below average for size and position – he wins as many headers as the smaller Wijnaldum.

Joel Matip’s number of aerial wins per game (2.2) is average for the position (centre-back) but below average for his height – with such giants averaging 3.3 per game. So one potential solution hasn’t really worked out in that regard, as yet. His win% is mediocre too. The image below shows the relative aerial strength of the Reds’ last season and this, with Benteke included merely to show the option open to Klopp.

Perhaps Matip needs to toughen up a bit too, with the Premier League a brutal battleground of bulk and bastardry that he has to get used to. So far his best assets have been on the deck (passing and intercepting; general reading of the game), although he will still win headers, sometimes without even needing to jump. But Dejan Lovren is the more dominant of the two first-choice centre-backs in the air.

Both Daniel Sturridge and Divock Origi are below average in both duels won for height and for position; although this season Roberto Firmino has risen from a very-below-average 0.3 aerial wins per game last season to 1.9 now, which is over the twice the number usually won by players of his height. This season Firmino has challenged for nearly four times as many aerial battles per game as Sturridge; equally, Divock Origi has also challenged for nearly four times as many aerial duels as Sturridge. (Is this because balls are played into Sturridge’s feet more often, or does he not even bother to challenge?)

At first I thought this change with Firmino may be a result of acclimatising, and also his method of looking at the defender first rather than just jumping in hope (which some referees automatically penalise, as if looking at your opponent means you’re going to target him, rather than just knowing where he is and when you might be hit by his flailing elbow).

But Firmino has contested a staggering 158 aerial duels this season – 12th in the whole league (and several more than Ibrahimovic) – but has won only 31% of them. I guess this is because he is the only forward player the Reds can hit; little Sadio Mané also ranks 3rd in the team, having contested 96 aerial duels – which is only seven fewer than Lovren – but given his height, won only 33%, to the Croat’s 63%. (However, watching him against Burnley today, with all these stats in mind, he won at least two aerial duels where he flicked the ball on to Origi. Origi, meanwhile, struggled to win the aerial battles.)

But Lallana and Coutinho aren’t going to win many battles for headers. None of Liverpool’s centre-forwards are dominant in the air. Daniel Sturridge is a lovely header of a ball, but on duels is appalling, at 17%. Divock Origi can head a ball, and is tall, but is only a little better, at 23%. So Firmino and Mané are actually the best, per duel, at 31-33%.

This means that even Liverpool’s best attackers are winning only a third of all aerial battles, and their worst (Coutinho) wins only 13% of the two-per-game he goes in for.

Liverpool have no tall wide players, either on the wings or as full-backs, to look for with long goal-kicks, and it may be part of the reason they try to play short ones out from the back.

(But that can create nervousness, as seen at Man City too; although I do feel British cynics love to laugh at such crazy continental ideas, when building from the back can often be better than just lumping long goal-kicks straight to the opposition. I also don’t think the fans booing Mignolet for taking a short one is anything other than hugely unhelpful, but it’s part of the narrative of “no fannying around with it”.)

And of course, the lack of height on the flanks also makes for far fewer dominant aerial players to attack and defend set-pieces; there just aren’t many tall players in the team. It really is a problem. As a team the Reds just aren’t very successful in the air; again, part of it is being the smallest side, but also, most of the players are also below average in the air for their height, too (or below average for the position they play).

Mamadou Sakho was one of those who was above average for both height and position, but while he has been missed (at times), it’s clear that after three breaches of club discipline in the summer of 2016 you have to respect the manager’s code of conduct, especially when team unity is essentially about everyone doing what is asked of them (and no one getting away with being lax). To ostracise a player you later need may well be cutting off your nose to spite your face; but to abandon all discipline is taking a knife to your eyes, ears and mouth too. If a manager has no say over discipline, and is seen to not stick to his own rules, he’s a lame duck.

Somewhat weirdly, the Liverpool player who attempts the most aerial challenges per game is Lucas Leiva, at almost 7 per match (winning roughly half of them). Origi is next, at around 6 contests, but as noted, he wins less than a quarter.

James Milner is one standout in the air: at 1.7 aerial duels won per game, he is well above the average; winning more in the air than even ex-Liverpool defender Martin Kelly (over 6’2”) at Palace, who only averages 1.1 per game over the past two seasons. But Kelly wins 65% of his, compared to Milner’s 44%. This is because Milner (through choice, or targeting?) is involved in as many aerial duels per match as Joel Matip (just under four). If you’re playing against teams with full-backs as tall as Kelly, you probably don’t try and hit angled balls to the far post.

However, you may think you miss Moreno’s pace and unpredictability, but to want him back in this side, especially without Lovren, in games against teams like Burnley, is asking for trouble.

On the subject of Milner and his position, one standout from last season was Joe Gomez: almost two headers won per game; above average for both his height and his position, which was left-back. Hopefully he’ll complete his recovery this season with plenty of football in the U23s (where he is impressing) and be in contention for either full-back or centre-back next season – although you almost never see 19-year-old centre-backs at big clubs, as the mistakes they inevitably make can be costly.

Is Bigger Better? – Liverpool vs Opposition on Height

I went through the data and examined Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool results against all the teams his side has faced more than once, to try and find some clear evidence of a pattern in relation to the height of the opposition. Did height make a difference?

Well, I found little but confusion. Perhaps this is because Liverpool can impose their passing, pressing and counter-attacking game on big-bastard opponents sometimes (perhaps more easily at home) but be bullied at other times (more so away). This contrast was clear within just one game – the first half against Burnley today, and the second half, when the Reds got on the ball – until the last 15 minutes, when it was batten-down-the-hatches again.

This was certainly true of Watford, who provide the most interesting example. Liverpool were bullied away last season, but not in the two home games against them under Klopp. So overall, Liverpool have a good record against Watford – the tallest team from the past two seasons, at an average of 187.5cm, or a whopping 6’1” per player.

But the Reds have had that one game – and the only one against them so far away from Anfield – where they were clearly bullied (albeit after the Reds’ reserve keeper threw one in at the start of the match). Indeed, Watford aren’t only tall but if the weight figures are to be trusted, they are by a significant distance the heaviest side, too, by several kilos per player – with even more of a lead on weight than height. (Stoke are the 2nd-tallest team, but only the 5th-heaviest; partly down to Peter Crouch, I’d imagine, who weighs less than a baby grasshopper.)

To highlight the issues Watford’s strengths, over the past two seasons no fewer than 833 Premier League players have contested at least one aerial duel (obviously many of the individuals in that 833 are counted twice: last season and this season, if they appeared in both campaigns.) Troy Deeney appears twice in the top ten – 6th and 7th place – with 6.2 and 5.7 headers won in aerial duels per game in 2015/16 and 2016/17 respectively. His aerial win percentage isn’t the greatest – only 41% – but on average he contests no fewer than thirteen aerial duels per game.

(This takes us back to Jamie Vardy: the Leicester man loses more than he wins, as you might expect at 5’10”, but he contests more than seven per game, and wins an average of three – which is more in sheer quantity than Joel Matip wins in a game. And Vardy wins far more than someone for his height usually does. And just when you’re expecting another high ball, one is played low down the sides.)

Remember, the aerial game is all about chaos. At Leicester last month, Liverpool were assaulted by a succession of incredible long throws, on top of a team breaking their own sprint records (Vardy) and making more tackles than any club has this season bar two occasions (both Southampton). Although the Reds just about defended the bombardment, it made the team nervy; and the second goal came from the second phase of play after a long-throw. (And as noted, Burnley almost equalised today, with Lowton shooting over.)

As we saw even Barcelona doing late-on against PSG, such tactics unsettle and unnerve. Just by placing himself up front, Barcelona’s third-tallest player, the goalkeeper Ter Stegen, altered the dynamic of the final two minutes, being in the box for four or five crosses, and on the penalty spot as the pass for the incredible 6th Catalan goal sailed directly over his head. He didn’t get a touch, but how much panic does such a tactic create? Was Sergi Roberto able to steal in unmarked in part because of this chaos?

The long-ball game is built on creating this kind of mayhem, although the very best teams tend to resort to it only in desperation, as its total unpredictability (of bounce) makes it less of a weapon, on the law of averages, than elite skill; whereas for the unskilled, the unpredictability exceeds the sum of their limited creative powers. However, with five minutes left, you may resort to it if skill is hitting a brick wall. Those who have little skill will rely on chaos instead. Burnley spent the entire second half today trying it.

From looking at these metrics from within the English game you can see which teams get the ball into their strikers in the air, either from long passes from deep, or from crosses; and these seem to be the teams that most trouble Liverpool. Perhaps the fact that they also often ‘park the bus’, and play longer to robust and/or pacy strikers, is also part of the problem. Remember, in this piece I’m not trying to say that a lack of height (and power) is the root of all Liverpool’s problems.

In 8th place on number of headers won is Sam Vokes, with 5.6, for Burnley this season – and he contests a staggering seventeen per game, the second highest amount after Leicester’s Ulloa, who averages 19 per match (but from far fewer appearances). Vokes didn’t start today, but Burnley still went long from the first minute to the last.

Maybe it’s coincidental, but Burnley and Watford (and Leicester) are away games where Liverpool have been accused of being mentally weak, when I think it’s the more understandable issue of physical weakness and a more direct game.

Only Christian Benteke (385) has contested more headers this season than Deeney (363) and Vokes (298). Fernando Llorente – architect of Swansea’s win at Anfield – is 6th (208), and Bournemouth’s Steve Cook is 9th; two big players who caused Liverpool a lot of problems this season. (Bournemouth are not a particularly tall side. However, they benefitted from the chaos approach at the end of the game, combined with Loris Karius’ nerves, and Cook was part of that.)

Zlatan Ibrahimovic is in the top 20 for number of aerial duels contested, but at 6’5” he’s not even United’s best player in the air. Indeed, the player with the best aerial win percentage in the league – at over 80% – is Marouane Fellaini.

These are two more players who denied Liverpool points late on in the league via aerial situations. (Fellaini rising above four smaller Liverpool players to hit the bar for Rooney to turn it in last season, and this season, Fellaini again winning the ball in the air before it fell to Ibrahimovic to get the late headed equaliser. Chaos approach plus giants = a chance.) He may have all the skill and finesse of a rotted carthorse carcass whose bones and sinew have been spread far and wide, but Fellaini is hard to mark on high balls and crosses (the elbows he swings helps his cause, too).

What’s weird is that Liverpool have actually owned the three strikers with the highest quantity of aerial-duel wins in the past two seasons: 1) Benteke, 2) Carroll and 3) Crouch. There have been these fleeting fascinations with giants, none of which lasted for very long. Perhaps these were too big; and the aim should be to become a bigger side, on average (if the quality is there too), rather than one totemic striker – unless that striker is happy to be a bit-part/Plan B option. (And again, not all Plan Bs have to be long-ball, but chaos can work.)

Obviously Crouch’s time at the Reds dates back over a decade, and unlike the other two he was something of a success – at least until Rafa Benítez upgraded to the smaller but better Fernando Torres. Of course, even Torres was 6’1”, and like Robert Lewandowski, the ideal size for an all-round, highly-mobile centre-forward – the kind Liverpool could arguably use right now (even speaking as a Roberto Firmino fan).

Unfortunately, Mario Balotelli also perfectly fit the physical mould; just not the mental one. (He had the ability as well as the physique, but just lacked professionalism and hunger.) Divock Origi is big, but he’s still young (21) and fairly lean, and just doesn’t win enough in the air. I still think he could develop into a world-class striker within a couple of years, as he has all the raw attributes, but equally, it’s getting the game-time to develop; the catch-22 for all players of his quality and age. Would fans accept a year of Origi playing regularly and being hot and cold as he potentially develops into the answer? Or will he be like Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang at Milan, who drifted after a lack of game-time and various loans, until, aged 24, he was signed by Klopp at Borussia Dortmund and is now one of the game’s best forwards? (Or will Origi be like other players who jut fade away?)

But these brief flirtations with giants shows Liverpool’s travails when trying to overcome the physical aspects of English football; the need to be big and strong enough to cope with the aggressive sides, without losing the flair that, on average, is provided best by diminutive technicians.

Under Damien Comolli and Kenny Dalglish, the buys were almost all big and strong: they went for size and power (and skill, too, but not excessively so). However, in 2011/12 Liverpool proved to be a tough cup team, who were hard to beat, but the league form petered away in a series of low-scoring draws and narrow defeats. There wasn’t enough guile.

Big players like Carroll, Jose Enrique, Charlie Adam, Sebastian Coates and Jordan Henderson – all six-footers, and some well over six foot – were not doing well enough on the whole, although Henderson was young and in his first season, playing on the right, and has since gone on to thrive, and of course, beef up with age (while Coates was too young at the time to be judged harshly – big centre-backs usually come of age in their mid-20s.)

Even the “flair” player they bought, Stewart Downing, was 5’11”, in contrast to the 5’7” of Juan Mata, the player supposedly overlooked in favour of the English winger. And of course, Luis Suárez – their crowing glory – stands 6’0”, and would be absolutely perfect for this Liverpool team right now (or indeed, any team in the world), with his supernatural strength and hunger – no pun intended. But of course, after the third bite of his career, and with him wanting out, Liverpool probably had to sell or risk losing him for an unprecedented ban (20 games if he bit someone again; 100 if he ate someone whole).

Of course, Liverpool then swung from one extreme to the other, as often happens when changing manager – the complete opposite approach gets adopted. In came Brendan Rodgers and out went most of those tall players, and in came Joe Allen, Oussama Assaidi, Samed Yesil and Fabio Borini. This was Liverpool’s “Barcelona” phase; Rodgers stating how much he liked the Catalan model, and how he wanted to give small players like Joe Allen a chance. (A noble idea that I supported at the time, but which appears to have come undone on the battleground of the Premier League.)

Rodgers instantly eschewed Andy Carroll, in much the same way that Klopp later jettisoned Christian Benteke, although at least the German didn’t leave himself short of a striker in the process.

But Benteke had only come in because, after three seasons, Rodgers’ smaller team needed an attacking focal point, and a target for out-balls to beat the press teams were putting the Reds under. Benteke looked a more technically gifted player than Carroll, and certainly appeared quicker during his Aston Villa days, but neither proved a satisfying solution once at Liverpool. Both looked lost in teams that were not constantly serving the ball in the air, but at the same time, too often the team often went long from the back just because they could. It’s a hard balance to strike.

So, going big-bastard (Dalglish/Comolli) proved no better a solution than going small and technical (Rodgers/Committee), in terms of overall recruitment. Quality is always a vital component. But if you have too many small players, or too many big beefy bodyguards, you can miss the perfect balance. Right now I’d say that Liverpool have a surfeit of smaller players – although mostly better small players than last season.

Big Six Reversal

One area where there appeared to be a clear correlation on height and results – although the sample sizes are smaller – is in the battles versus the other top six/‘big six’ clubs. We all know how well Liverpool do in these fixtures, but the Reds’ points-per-game clearly gets worse the taller the opposition are. (Note: this includes cup games, converted to three, one or zero points.)

City are, on average, the smallest top six side, aside from Liverpool themselves (with the Reds, as mentioned, the smallest in the entire top division). Liverpool have an excellent record against City under Klopp: three wins and a draw (which was lost on the shootout, where height plays no part, goalkeeper aside). Arsenal are the second smallest of the other five clubs, although they did go bigger against Liverpool last week. The Reds have their 2nd-best top-six PPG against the Gunners.

Then come Chelsea, who sit in the middle in terms of overall height; ranking 3rd from the top six in average height, and Liverpool’s results against them rank 3rd. Liverpool’s 2nd-worst set of results are against Spurs, the 2nd-tallest in the top six. And the Reds’ worst PPG is against United, who are the tallest – some two inches, on average, taller than the Reds.

Perhaps one of the reasons Liverpool can beat City more easily is because, in the absence of Vincent Kompany, there’s just not a lot of aerial threat. Neither Liverpool nor City have a player in the top 30 for aerial win percentages. Indeed, Liverpool’s top player in this respect – Dejan Lovren – ranks 66th, at 63.1%; while Joel Matip only just scrapes into the top 100, at under 60%.

By contrast, Manchester United occupy three of the top 12 places for aerial win percentage. And interestingly, Kyle Walker – Spurs’ right-back – has a better record in the air, per duel, than any Liverpool player. By contrast, Nathaniel Clyne ranks 381st this season in the air, winning just 17% of his duels – although he doesn’t contest very many.

Indeed, Nathaniel Clyne’s problems in the air detract from his otherwise excellent defensive game (the attacking is far more hit-and-miss). He won just 0.3 duels won per game last season, and it’s 0.3 again this season; certainly some consistency there, as the Liverpool player who wins the fewest aerial duels per game (and at the 2nd-lowest percentage, 17.5%). Of course, with him upfield a lot on breaks, and then kept back on the Reds’ set-pieces, he contests fewer than two per game. Even so, a ball to the far post will see Clyne almost certainly beaten in the air. Of the regular starters, only Philippe Coutinho is worse in the air, and in his case, defending is not a major requirement.

If we assume that Liverpool are equally motivated for all of these big games (and if anything, for United a bit more), then there are none of the “not up for it” variables. In the head-to-heads, where both teams are motivated, Liverpool’s results get increasingly worse the taller the opposition.

The Wimbledons of the 21st Century

Presumably Dalglish’s thinking in the late ‘80s was that if he put Liverpool’s biggest players up against Wimbledon’s – heavyweights against heavyweights – his own side’s superior technique and pedigree would win the day (so, the Reds’ Muhammad Alis pitted against the Dons’ Frank Brunos).

The decision to leave out Beardsley was presumably because as long as Liverpool were shorter, there was always more risk to the randomness of aerial challenges and the bounce of the ball, and of course, the chaotic fights on set-piece. Even if Beardsley could open them up (as he did in the 1988 FA Cup final before the goal was wrongly chalked off in order to give the Reds a free-kick on the edge of the box), Dalglish preferred to fight fire with fire.

So overall, Liverpool weren’t quite as skilful without the impish Beardsley, but they were more robust. Beardsley was an excellent player – however, if he was as good as Lionel Messi or, to use a more contemporaneous example, Diego Maradona, then height be damned. If you’re that good then height becomes less relevant.

(Which is kind of what Barcelona experienced with Messi, Xavi, Iniesta, Mascherano, Pedro, et al, all at once. They were just too good for the cloggers, not that Spain presumably has as many as England. But that is a rare level of skill.)

Perhaps the blueprint of the successful big side belongs to Jose Mourinho. As noted, his United side top most of the aerial metrics. They’re still not in the top four in the league table, of course, but their overall form for 25-or-so games suggests they’re on the rise. Overall he tends to buy big, powerful players, and funnily enough, he did just that again in the summer.

Of course, as height is an ‘asset’ – just like skill, stamina, pace, mentality and strength – you pay more for players who have all of these traits than those who only have a few. Paul Pogba wouldn’t have cost as much if he was 5’8”, because being big is part of his skill-set. He wins over 60% of his aerial duels; contesting, on average, five a game, and winning three. (Only one Liverpool player has won headers at a better rate this season than the Frenchman – Dejan Lovren – and Pogba isn’t by any stretch United’s best player in the air, as he showed in a bizarre display against Liverpool.)

Perhaps Klopp’s thinking is that his smaller players are good enough to impose their will on the game, rather than making too many concessions to physicality. And in the long-term, that may be right. Winning the ball with pressing, and passing it on the deck – and improving at the things the team does well – will still reap some rewards. Equally, I think that more physical presence within the team would be helpful. (And he may agree, for all I know.)

Such is Liverpool’s problem with tall teams (or tall players getting free on set-pieces), that even sodding Arsenal came to Anfield with three six-footers up front, and looked to play direct; in part to bypass the press, but also because Liverpool lined up in the previous game with three of the back four standing 5’10” or under, and a goalkeeper who is not exactly the most proactive at dealing with aerial situations (even if he has improved at it, and was excellent at it against Burnley).

Fortunately, it’s not really Arsenal’s strong suit – they don’t practice and play that way every week. And they’re not particularly aggressive with it; they were tall, but not physical. They’re “nice” big guys. The Gunners then switched to Plan B: unleash the pace, and again, that’s another thing Liverpool can struggle with, but most defences do.

As well as losing some of the best aerial combatants, some big problems in the air from last season have been eradicated: the terrible aerial wins per-game of Kolo Toure (at just 0.6 per game it was a third of Lucas’ 1.8 this season and a quarter of Lucas’ 2.3 last season; both are small centre-backs, of course, at c.5’10”). Jordon Ibe added nothing aerially, and although he was sold because of a lack of progress in terms of his overall game, he was another small player who added nothing on set-pieces at either end.

And obviously Alberto Moreno was a total liability in this area, at just 0.4 duels won per game, although his win% (33%) isn’t too bad – but he was a clear weak link with crosses to the far post. As with Emre Can playing in midfield, one of the reasons Milner plays ahead of Moreno is his relative aerial prowess.

If you asked me if I’d rather Liverpool had kept Christian Benteke instead of purchasing Sadio Mané then I’d say No Way. But without the option of Benteke, Liverpool are weaker in defence and more easily bullied. (Not that Benteke marked perfectly at corners – there was one occasion where he was totally asleep. And not that keeping Benteke as a sub would have meant he’d be happy and confident. But overall, he’d have helped mark better than Mané does. However, Mané is a clear upgrade.)

No one wants tall strikers just to help defend set-pieces at the other end, but for me the upgrade from Benteke to Mané is part of the problem as well as being part of the solution.

That’s how football is – with everything you remove from or add to the team there are pros and cons. If Liverpool had Benteke to throw on late in games, or to play in certain fixtures (Leicester away), maybe the Reds could be more physical. Equally, Liverpool’s football has generally been better since moving away from Benteke, just as it was after the club moved away from Andy Carroll.

Some more aggression, size and strength when defending against the set-piece/long-ball games of certain teams would still come in handy, I feel. Until then, a certain physicality does provide a very good reason why Lovren, Can, Milner and even Lucas are called upon more often that certain fans might like. It’s easy to pick at individuals’ flaws, but a certain amount of heft and thew is required.

Conclusion

This season Jürgen Klopp improved Liverpool’s “football”. But once it reverted to a battle, in the winter, the Reds were ill-equipped. (Man City may have had the same problems.) Against Spurs and Arsenal more recently it was back to football for the Reds; but maybe other teams will make it a battle, in the way that Leicester did, and in the way Burnley gave Liverpool a scare today.

Of course, Liverpool have been at their best – as you’d expect – with all the key men fit, and with adequate time to prepare (but not two weeks in which to lose sharpness). So it’s not just a question of physicality, but that the Reds’ best players – like Coutinho, Henderson and even Lovren (in the air) – need to be available, and also fully fit, to make their quality count. The Premier League does not easily carry players coming back from injury, just as it doesn’t go easy on short-arses.

Also, Liverpool’s bigger, stronger players were either missing or out of form during the slump, or indeed, just out of form all season. Both Matip and Lovren missed games, while Emre Can hasn’t played as well this season (although he’s adding goals and still giving his all), and neither has Divock Origi – although both are still young enough to kick on again, and neither particularly worries me; this is normal development for most players (although Can may not sign his new contract). Both showed glimpses of what they can do against Arsenal, and the pair were involved in both of Liverpool’s goals today.

And of course, Can has Liverpool’s 3rd-best win percentage in the air (57.1% compared to Lovren’s 63.1% and Matip’s 59.7%), which brings me back to the opening paragraph, and one of the reasons why he plays games is this brutal, unforgiving league.

And obviously another big young player, Marko Grujic, has been injured, and would still be adapting anyway. These are tall, high-level technical players for their age, but not yet “bruisers” (although Can is getting there). Young players usually get physically stronger with age, but even if they don’t (such as Peter Crouch), they can learn how to use their bodies better.

The loaning of Steven Caulker last season – at the same time Grujic and Matip were “pre”-signed – was another nod to the aerial issue, but he was never really seen (except as an emergency centre-forward against Arsenal, causing chaos to reign). Size without sufficient quality is not the way forward.

But I’d like to see Liverpool have some more powerful options. However, if not, this research shows the importance of players like Lovren, Milner and Can, and how losing them – or replacing them – may come with down-sides too, if the players aren’t as strong in the air (or indeed, as strong in all physical senses). To get smaller or slighter players means that they must be significantly better in terms of overall contribution – such as Mané replacing Benteke.

But on a personal level, I’d just like to not have to change underwear several times during a game due to every time a high ball goes into the Reds’ area.