By Tim James.

Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool are on the up. In nearly all aspects of play, they have clearly improved in their tactical ideas and execution of those concepts. However, one area where there is still room for improvement is in defending set pieces. Recent games against Hull, Swansea and West Brom have seen set pieces remove the possibility of a clean sheet. If the problem persists, there may be bigger consequences.

Man vs. zonal: a cultural divide

Liverpool fans will be familiar with the man vs. zonal debate. Whilst it has become a particularly pertinent issue in Liverpool’s approach to attacking certain opponents in open play, the mainstream media has long recognised the debate in relation to defending set pieces. Rafa Benitez was met with huge amounts of criticism during his time on Merseyside, despite evidence that his approach created a strong set piece defence.

This resistance was largely due to cultural differences and an unfamiliarity with the concept of zonal marking in English football. Since that time, more top foreign managers have made the trip across the channel, and therefore the use of zonal marking at set pieces (and in open play) has increased. With it, so has the criticism from the mainstream media.

What is often ignored, though, is the implementation of the system. Inevitably, when a team who implements a zonal-based system concedes from a set-piece, the very idea of zonal marking is criticised rather than the execution. When a man-marking team concedes, a player is blamed and the system survives unscathed.

It is claimed that it is easier to immediately identify the fault of blame when each player matches up 1v1 with their opponent. This ignores the interaction between players, and the ease at which a team can disrupt man-marking with such a cluster of players in a small space. However, even if this were acknowledged, it should not be a reason to implement a particular system.

If the ease of understanding and blame allocation is the deciding factor in choosing which system of set-piece defence to employ, it is an indictment of the coach not the system. If the nuances of each system are not fully understand by the coach so as to allocate blame effectively, then perhaps it is the coach’s responsibility to expand his understanding.

However, Liverpool do use a part-zonal system. Still the goals come flying in. Pundits and fans alike have commented on this inability to defend corners particularly – this may be due to their proclivity for a part-zonal system, but there also seems to be clear basis for Liverpool’s struggles.

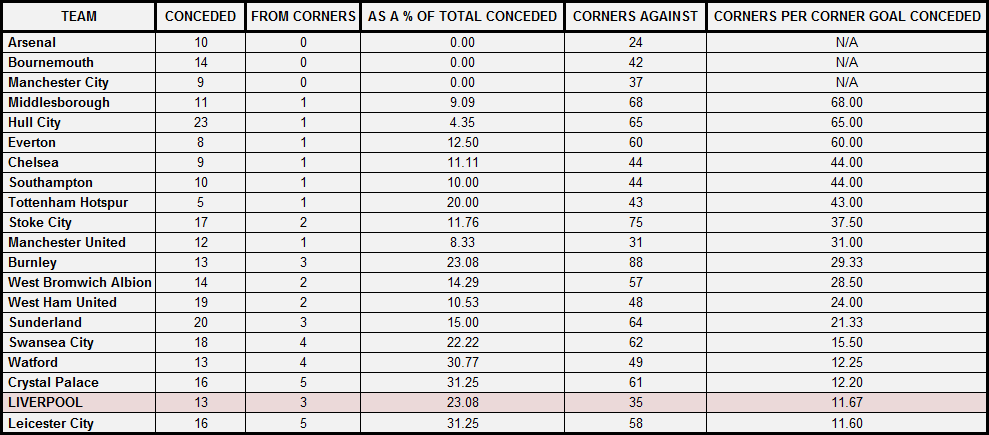

Premier League teams and their 2016/17 performance at defensive corners. It takes approximately 12 corners to score from one against Liverpool at the moment, second worst in the league.

Liverpool’s defence is generally really good, and means Liverpool don’t have to defend as many corners. Indeed, Jurgen Klopp himself recently inferred that the best way to defend corners is to not concede them at all. Even with this considered, Liverpool have still conceded more than 20% of their Premier League goals from corners this season.

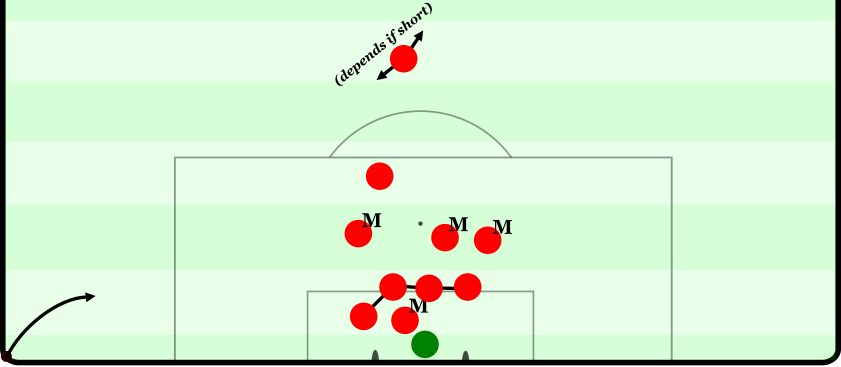

The base set-up is a part-zonal, part-man marking system. Four men are staggered along the six-yard box, and another (usually Sadio Mane) is stationed near the edge of the box to potentially initiate attacking transitions. Then there are three or four man-markers, depending on the opposition.

The default setup whilst defending corners, with only minor adjustments made on a game-by-game basis (M = man-marker)

Typically, the best headers of the opposition are man-marked. This effectively creates double coverage – as the dangerous zones are covered, and the dangerous opponents are marked. Seems logical, but it has a major downside.

Identifying the issues

First contact

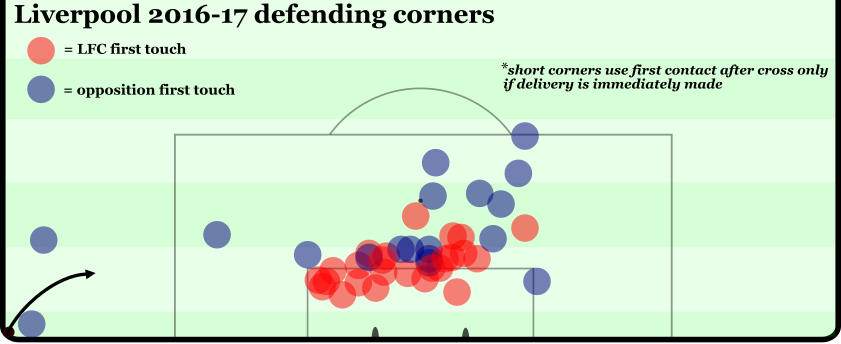

Liverpool generally make first contact on defensive corners. This is, however, not the case in all areas of the box.

First contact locations

That’s pretty good coverage of the front post, and the six-yard box generally. This is to be expected given Liverpool’s set-up of two men zonally marking the near-post space, and the man-marker following the inevitable near-post run of one opponent. The natural gravity of the ball in these situations should not be ignored either – if a near-post cross is delivered then the near-side central defender (usually Matip) will naturally step towards it.

The only minor weakness is in the centre of that area, where the opposition have five times managed to win first contact. Within the standard set-up, issues have also arisen with co-ordination between the two central players. Twice Klavan has run under the ball and the opposition have been able to get first contact in the gap between him and the far-post zonal marker. Lovren is slightly more dependable in this sense, but the other key chance was created by Tottenham, where a large space was left between him and Matip.

Recently, the set-up has shifted slightly and Firmino has played a role as one of the zonal-markers, usually between Matip and Lovren. Two of the opposition first contacts in this area are down to him losing individual duels; first against West Brom, and then he was outjumped by Christian Benteke. Firmino moving into this position may be Liverpool’s answer to the poor co-ordination between the two central players previously, but it does not seem like a long-term solution.

However, in almost all of these instances, multiple mistakes were made to allow the opposition first contact. For example, Firmino should not be allowed into an individual duel with Christian Benteke anyway, because he was man-marked. Against a strict man-marking system, one mistake is more likely to lead to a goal. This was evident in the Crystal Palace game, where Lovren and Matip found it easy to lose their opponents. Mistakes will always happen, and the key role of an effective defensive structure at corners is to minimise the effect of these mistakes.

Second balls

Despite minor worries, first contact does not seem to represent Liverpool’s main issue whilst defending corners. The importance of winning second balls should also be acknowledged, and becomes particularly important if the structure for defending first contact leaves the opposition in a favourable situation.

The key advantage of zonal marking is that you are not reactive to the opposition. Man-markers can be manipulated by the opposition to create space in a dangerous area. However, Liverpool use a mixed system, and this same effect can be created.

As the most dangerous headers of the ball are covered by the man-marking, they are typically followed into the six-yard box. This is because they tend to be the players who most aggressively compete to win the first contact. When this happens the defence collapses, and a huge cluster of players is created along one vertical line, generally around the six-yard box.

For headers straight from the cross, this is largely fine. Headers from beyond this distance are converted at a very low rate. The difficulty, however, comes when the ball is not completely cleared with the first contact. This can create second ball opportunities, and gives the opposition a chance to create much more dangerous shots if the defence has collapsed.

Some particularly pertinent examples illustrating this are shown below. Whilst both goals are scored with second balls behind the defence, Chadli’s shot also indicates that there is space available in front of the defence too. This is because a straight line defends neither of these areas particularly well if the ball is not cleared initially.

Solving the issues

Just like transitions, the result of chaotic second ball situations is often due to the initial organisation. One option would be to increase the number of zonal markers, to ensure the box is always well spaced, even after the defense collapses from onrushing opposition runs. This could potentially be improved by ensuring the zonal component of the system is not restricted to a line along the six-yard box and a man on the edge.

For example, having two zonal-markers positioned in the centre of the box around 10 yards out would mean almost all dangerous areas are covered. But there are numerous potential marking combinations – what is likely to be more important is implementing sound principles that all the players can employ.

Flat-footedness

The way Liverpool defend those zonally, it means the central defenders can run and get the jump on them. I’m not mad about that” – Niall Quinn

Quinn’s critique of Liverpool’s system is more nuanced than many pundits, and is correct. In many cases, Liverpool’s zonal defenders have been left in an individual duel against an onrushing attacker – this standing start gives them an immediate disadvantage. Firmino does not have the height of Lovren or Matip, so it makes sense that he would struggle. When combined with the standing position he is forced to jump from, it is no wonder he has already lost two aerial duels from set pieces.

However, there is no inherent reason why a zonal-system needs to be so flat-footed. It is easier to co-ordinate the zonal base of the system if they are standing still, but increased training time could allow simultaneous motions towards the ball. A simple rule to allow for this is to aggressively attack the space in front of you – if the ball goes over your head then it is the responsibility of the player behind. Many successful teams implement a similar mixed-marking approach, but are more successful at clearing the initial cross, making second balls less of an issue.

This already happens occasionally in Liverpool’s system, but it seems impulsive rather than strategic. Joel Matip will often adjust his positioning based on the trajectory of the cross, but teammates’ reactions to his movement is not satisfactory. This contributes to the gap between he and Lovren, and could be solved by everyone in the zone adjusting to Matip’s new position. This sort of adjustment would give all the players a moving start, and therefore maximise their jump height potential.

Goalkeepers

Another contributor to defensive set pieces that should not be ignored are the goalkeepers. Mignolet’s difficulty in consistently claiming crosses has created long-term problems for Liverpool, and Karius has had similar issues in his limited time at Anfield.

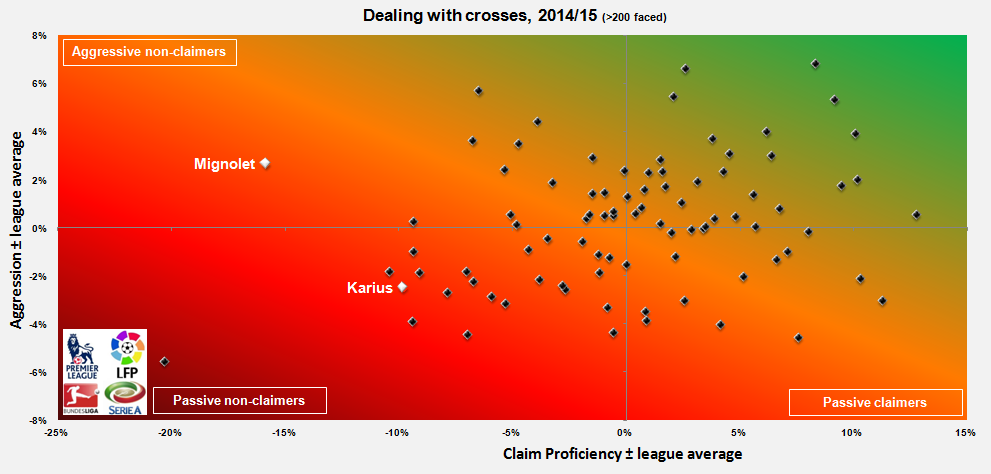

Both Mignolet and Karius have struggled from crosses (graph from @Sam_Jackson94).

This data is two seasons old – Mignolet and particularly Karius may have improved in the meantime. But it seems to reaffirm many eye-test conclusions from Liverpool and Mainz fans.

Having a goalkeeper who is aggressive and competent in aerial duels allows the zonal-marking to shift forward one or two yards away from goal as the space behind them is well-covered. This may not seem like a huge amount, but it can make a huge difference to the conversion rate of headers, and also leave the team in a better position to deal with the second ball if it isn’t cleared initially.

Conclusion

The team doesn’t actually concede a huge amount of chances from corners, but they tend to be big chances when they do. This is because a second ball received in space allows the opposition to take a shot from the ground rather than with their head, which is obviously not ideal. Reducing the likelihood of this occurring should be Liverpool’s man aim when next tweaking their set piece defence.

This may be through structural alterations, such as adding another vertical ‘line’ of zonal markers. Improving the team’s co-ordination to each other’s movements would also accommodate more aggressive pursuit of the ball without leaving pockets of space for the opposition to exploit. Additionally, implementing general principles of play and acknowledging variability of delivery would allow the zonal marking (particularly the additional line) to be more efficient.