By Liam Blake

Resistance is futile. Jurgen Klopp would have captivated me even if he’d pitched up at the Emirates last Friday, as a year or so ago I thought he might. As many times as we’ve been round the block now, I found myself gleefully giving way nonetheless like the stern-faced judge in a Hollywood movie who chucks his gavel over his shoulder in mock despair and with a what-the-heck shrug of his shoulders joins in with the happy throng below. Seasoned hacks swooned and giggled, enrapt like the girls sitting on the front row of Indy’s archeology lecture in ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’. It’s a wonder anyone took notes. He’s irresistible, a gust of fresh air that blew through long before he was even in situ. He’d arrived before he’d arrived. But then of course we all wanted to fall in love. We needed to. He’s arrived in Act Four of FSG’s tenure like a deus ex machina and for the press, Klopp is a Godsend, a fountain of good copy. True, they have Mourinho in a strange new incarnation – backed into a corner for now but a whole new story for that – and Van Gaal who, though baffling and entertaining as ever, appears to have one eye on his much-signposted retirement. Klopp will re-energise the league, never mind Liverpool FC.

As for us, we’re hugging a hoodie now partly because, even when the going was good during 2013-2014, we still didn’t truly embrace Brendan Rodgers. The lightning rods for our feelings then – which included a fair amount of giddy bewilderment – were largely to be found out on the pitch rather than in the technical area. Rodgers heard his name in song, but never quite lodged himself in our hearts. Minds, maybe. Then again, for a long time I almost felt that I didn’t understand football anymore. Now I see that it was Brendan Rodgers that I was struggling to understand. Klopp should, at the very least, remind us that football is a simple game. And I’m not implying that Rodgers was a fool. Or that Gary Lineker was right about the Germans always winning.

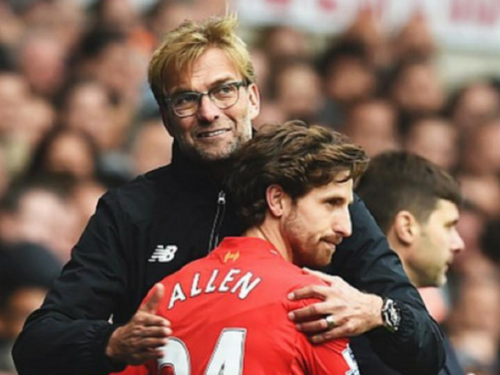

Klopp’s appointment has been celebrated with a lack of restraint not witnessed since Martin Broughton emerged triumphant on the steps of the High Court on October 13th, 2010. Just as we took a lifelong Chelsea supporter to our hearts and embraced NESV because they weren’t Hicks and Gillet, so too we’re throwing our arms around Jurgen because he isn’t Brendan. A little unseemly perhaps but forgivable and perfectly understandable in the wake of a period of stagnation throughout which none of us could any longer claim to know what Rodgers’ Liverpool was really all about. It all felt a little like working away dutifully at a longterm relationship when you knew in your heart it was running out of road, and meanwhile your eyes are following the most beautiful woman on the continent around the room and (gulp) she’s available. Let’s leave that analogy there, as it makes Klopp the bearded lady… Suffice to say, relief is a factor. And if indeed it seems a little premature, if there’s nothing to celebrate yet – and Klopp has, with a dentist’s dream of a smile, reminded us of this – then there’s a manifest sense at least that it’s all back in our hands. We’ve gone from bystanders to stakeholders in the space of days.

But of course we’re not just on the rebound. Hyperbolic as it may sound – and after the downhill tumble we’ve been on this last year and a half, the club deserves the nervous release of a bit of febrile fantasy before we all roll up our sleeves and get down to work again – there’s a compelling case to be made for this being the single most exciting managerial appointment the club has ever made. Never mind the hyperbollocks, that’s heresy, I hear you cry. But let’s remember first of all that Bill Shankly was a highly promising young manager who, though on the rise, was yet to cement his reputation. Klopp himself reminded us, after all, to judge a coach not on their arrival but rather years down the line. Later on Shankly himself was brought up short by the notion of his lieutenant as a manager, and the subsequent pattern of appointing from within – as much a natural consequence of serendipity as it was a matter of policy – maintained continuity. And while Dalglish’s initial appointment was a bold one, made with one eye on the future, it still held as a parallel detour from the established chain of succession rather than a break from it. Not until Houllier did we welcome an outsider. Even then this administrator, a man who looked every inch the former teacher, was greeted with a curiosity that had been stoked by his compatriot Wenger’s zeal for reform. The only obvious antecedent is Benitez who, like Klopp, had created a machine that rammed the citadel in his home country to take two titles at the expense of the established powers.

But there is no precedent for this. A young coach touted to succeed Guardiola at Bayern, who could realistically be expected to manage any of Europe’s powerhouse clubs and at some point surely his country, who as recently as May was the subject of a feature in Four Four Two magazine assessing what he might bring to Arsenal, City or United – not so much as a mention, even in passing, of little old Liverpool – and he’s been waiting to come to us. Pause for breath. A man who’s been a galvanising force in his domestic league’s resurgence in the global football consciousness, a man who comes with glowing and barely needed testimony from the great and the good of the sport’s dominant nation, even, um Gottes Willen!, from der Kaiser himself, and he sees us not as the poisoned chalice to rank alongside the England job, not as Tottenham, but as the challenge he’s been seeking. The natural next step. Breathe. It’s some complement, one that even now, just one match in, takes some digesting. ‘Klopportunity knocks’. Apologies, it’s the excitement. Better out than in, anyway.

The moment we’re in now is a little like that captured in the extended shot at the end of The Graduate. It’s that rarest of films, The Graduate, one in which absolutely every last thing works to create a whole that burrows down into your mind for good. The script, the set-pieces, the soundtrack, the editing, the direction and the performances, the cast. Dustin Hoffman and Katharine Ross. Katherine Ross. But for me that last shot before the end credits always comes to mind before all else. There’s the two of them, having found each other, flouted convention and flown in the face of generational wisdom. With no plan, they sprint for the bus and sit there breathless on the back seat behind a gaggle of nonplussed commuters, enrapt with each other. The director Mike Nichols kept the camera rolling long after ‘the end’ and kept the result in the edit. There’s no more dialogue, nothing more to be said, and what we get is a moment not of happy-ever-after but of uncertainty, of what-happens-next? There’s a dim realisation that, beyond the now, there lie years ahead that require a plan. Now that we’ve found love, what are we gonna do with it?

I’m not suggesting for one moment that we’ve been impulsive. I fear Brendan Rodgers knows only too well that we’ve been eyeing up Europe’s most eligible bachelor for quite some time now. And of course there’s a plan. I’ve never had any doubt that Benjamin and Elaine settled down and raised a family. Happy ever after. There’s a gigantic opportunity here and now for a newly galvanised club. It’s not necessarily FSG’s last stand as some are already suggesting, but it is worth considering exactly what the opportunity offers us.

Among the gleeful welcomes in the press, there have been some colourful anthropomorphisms. Barney Ronay, writing in the Guardian, described Klopp as ‘a very friendly life-sized cartoon cat’ – did he have a particular character in mind? – while someone who shall remain nameless, if only because their name escapes me, likened him to a Labrador. Well, I ask you, who among us could gaze upon the upturned face of a Labrador and remain stony of heart? Boundless energy and enthusiasm, I see that. Bouncy. But beyond that, the comparison falters. It is curious that there is something distinctly ‘unfootball’ about Klopp that’s truly endearing. He somehow doesn’t look like a football manager, he’s neither suit nor tracksuit but hoody. Looking at the photos of him arriving to take his first day’s training, he cuts a youthful figure. I think in modern football parlance you need to be the right side of fifty to be referred to as a ‘young manager’, and though Klopp is – just – you sense he’ll remain youthful for as long as he’s around. He looked like a Google employee arriving for work, a free-thinking radical in a duffle coat – zipped, no old school toggles – with a backpack full to the brim with ideas. It somehow wouldn’t have been a surprise to see him arrive at security on a scooter rather than a Porsche 4×4. He’s unconventional and impossible to dislike which, in itself, is a gigantic advantage – he seems impervious to the haters, he’s won on the unity ticket and he’s cast a huge cloak of goodwill around us that will take some unraveling. In terms of changing the atmosphere in and around the club, he’s already a revolutionary.

Were you to list his obvious attributes as a coach and manager, then that list would occupy the bulk of this piece. When he’s finally done with his football career, the business community will surely trample each other underfoot in the rush to help him set sail as a leadership guru. Perhaps he can fix VW. His fabled ‘ABS’ – Anti-Bayern System – in-your-face, heavy metal, vollgas fussball, call it what you will (he’s even rewrtiting the football lexicon!) was of course ripped off and replicated on a mass scale by the power he briefly toppled, leading Klopp to compare Bayern to the Chinese economy. For now he’s a beguiling mix of old school qualities and new, beloved of the football hipster for Gegenpress and a motivator and communicator par excellence. I was about to write that he’s honed his media image to perfection throughout years of stints in punditry on German TV but that would be to miss the point entirely. He’s child-like in his candour, there is no artifice – he is who he is. In short, you would struggle to convince anyone now that there is a quality necessary to management that he lacks.

So die grosse Chance – the great opportunity – is perhaps to use the moment to rethink, regroup and recast ourselves as the club in opposition, to get radical and innovative. A bit like the new Labour Party. Or is that the old Labour Party? How’s that going? Entirely the wrong analogy? Discuss.

Questions of identity have loomed large over the club as FSG have settled into their tenure as custodians. The largest of all, the one David Conn was effectively asking when he recently wrote about the ongoing issue of Liverpool’s post-Premiership identity in the Guardian and the one I most often find myself fielding in the pub, is this – are we still a big club?

Without wishing to seem like I’m sitting on the fence that many don’t even see is there, I can only say that there isn’t a yes/no answer to the question. In many respects we’re not a big club. We’re still to expand our capacity to match those of our rivals, though work is finally underway. We’re yet to win a title in the Premiership era and we cannot kid ourselves – that’s what big clubs do. Post-Benitez our European football has been played largely on Thursdays against opponents a lot of us are having to look up. When it comes to attracting – or indeed keeping – stellar talent, then we’ve been stuck for years in a moment that we can’t get out of, without wanting to get too U2 about it. Benitez’s machine was dismantled as ‘the best midfield in the world’ was broken up and shipped to Spain’s powerhouse rivals while Torres took his grand wrong turn. We’re forever a season or two away from losing our best player. It’s always only a matter of time before the rumours harden into fact – Suarez, Sterling, next Coutinho, we can only suppose. Though in rude health financially, we’re still somewhat off the pace. In other regards, however, we are still undeniably big. A global fanbase, in part a legacy of a rich history.

Ah, history. Now that’s big. We’ve got that. To the extent that, in recent years, when incoming Liverpool managers have taken their bows before the press, hushed reverence has become the default tone. Think of Rodgers paying lip service to Anfield’s ghosts on the wall in his velvety brogue. I didn’t at the time doubt his sincerity, but I did find myself wondering how well such an approach could ever serve us. In fact I wondered if it only to fettered us. Cut to Klopp’s take on the subject, neither irreverent nor unduly reverent, but fresh, deft and sure of touch. An outsider’s take. Fuck the past, kiss the future. Or, to put it more politely, history as foundation rather than burden – a launchpad, if you like. So we find ourselves encouraged to approach our history more lightly, not to carry it around. Perhaps we ought to swap it for whatever he’s carrying in his backpack.

Klopp has already spoken of the inhibition he saw in some Liverpool players’ eyes during recent games. The great gift he offers is freedom. That applies to player and fan alike and, I suspect, means freedom from the past, too. It requires a leap of faith, one that he’s already asked of us – doubter or believer, remember. As soon as I’d heard that I conducted a quick straw poll of my own, one friend texting back without hesitation that he was a ‘hoper’. I hadn’t thought this was multiple choice – Klopp didn’t give us ‘none of the above’ as an option. He was asking us to come with him. We have a leader now, something Rodgers, for all his coaching acumen, never was.

On occasion I find myself wondering what the link really is between Liverpool FC up until 1990 and the Liverpool that’s sporadically lit up the Premier League. LFC1, if you like, dominated a much smaller marketplace, reinvesting all of its profits in the best players available. LFC2 has struggled at times to adapt to an ultimately global market, one in which every club has access to a far wider pool of players. Everyone else caught up; we’re a slightly smaller fish in a much bigger pond.

So in a sense we’re the underdog. We have been for some time, but we’ve been slow to embrace it. If we do so now, we can punch above our weight. We can thrive. It’s clearly a situation in which Klopp himself thrives. And here the parallels between ourselves and Dortmund come thick and fast. In fact there’s an irresistible symmetry to it all, as though it were almost too good to be true. Both clubs have succeeded in stabilising themselves, having danced on the edge of a financial volcano. BVB had overstretched in the wake of unprecedented success in Europe under Ottmar Hitzfeld, to the point where they found themselves within a vote of oblivion. The 444 voters with a stake would hardly have opted against any chance of recouping what was owed, but BVB limped on under such restriction that even the incoming Klopp wasn’t to realise until later just how little money was available. In trimming the wage bill by offloading his two top scorers Mladen Petric and Alexander Frei and replacing them with Lewandowski (before he was Lewandowski), Klopp set about forging a modus operandi that even now ought to serve Liverpool well.

Having scaled the heights, BVB had to face facts. For all their striving – for all their spending – they were not a ‘big club’. That seems a ludicrous assertion to make when looking upon the die Gelbe Wand in all its glory, the pride of a stadium now holding 80,000 in a region that’s as much a football hotbed as the one Klopp now arrives in. But in the context of German football it’s the truth, as the club came to realise. In the Bundesliga there is only one big club, and there is little chance of that changing. That’s not to say that others like Dortmund and Bayer Leverkusen won’t storm the citadel as they have done in the recent past, and likely will again. But they won’t remain there to establish anything that might prove a longterm threat to Bayern. The same applies in Spain. Money, as Jonathan Wilson has noted recently, has congealed around Europe’s elite clubs to the extent that their being displaced seems inconceivable. It’s in this context that Klopp’s Liverpool must realign themselves.

Over a period of years I’ve come to a private accommodation with my inner supporter, largely for the benefit of my own sanity. ‘What if we never win it again?’ I would ask myself at periodic intervals, realising as the super-rich raced into the distance that there was in fact a very real chance that we might not. I’d always assumed that it might happen at some point in my life, but then I’d always assumed that at some point I’d own property, too. Like an actor having to digest the fact that he’ll never play the Dane, I’ve had to realign my expectations.

Having lanced the history boil, Klopp took aim at another in the days following his initial introduction. As a football culture that can be remarkably shrill – ‘we’re turning into Tottenham’, apparently – and lead-headed when it comes to the introduction of new ideas, we’d do well to listen to Jurgen’s observations as a newcomer. His take on money might refresh us all, and it might help propel our club. ‘Only here is it an obsession’ he’s noted. There’s enough of it about in Spain, Germany and Italy but if he’s suggesting that it’s only here that we feel the only way up is to spend, spend, spend, he may be right. ‘Here it is money, money, money,’ he went on. He’s not wrong. We’ve become addled by it. Money, or a comparative lack of it, breeds fear, too. We’re in an arms race here and we’ve convinced ourselves that when that star player signs on the line for Barca then all our hopes evaporate. Without Coutinho we’re doomed… Locked into that kind of mentality, failure becomes a kind of self-fulfilling prophesy. But I think a squad shorn of icons and star players may even be an advantage, it’d be exactly Klopp’s kind of squad after all.

It’s his way and his way alone. If we’re willing to take the leap of faith, and if Jurgen Klopp can succeed with a spot of neurolinguistic programming on a club scale, then we can storm the citadel even if we might never rebuild it. Hope in our hearts? It’s the hope that kills you remember. Believe…