By Paul Tomkins and Robert Radburn.

The following is something I wrote with my long-time collaborator Robert Radburn (we co-authored a ZX Spectrum game together while at school, but please don’t tell anybody). It takes my recent work on the scoring rates of strikers and expands it, with the addition of various interactive Tableau infographics. It was created for the #ironviz competition, which required the use of Wikipedia data. So if the data is wrong, don’t blame us (having said that, it looks fine to me).

The graphics on this site are screengrabs, and just a few of those from the main article – click on this Tableau link for the full-sized interactive ones.

Better to be a Drogba than an Owen?

50 Accomplished Goal Scorers

Obviously different players progress at different rates, meaning that you will always have prodigies and late-bloomers, with every shade in between.

Some fade out quickly, others burn brightly just before the dying of the light, while some just steadily chug along; they play/ed for different clubs, in teams of varying degrees of quality; they may be shunted into a variety of positions before they settle into the role of striker; and each one has his own unique fortune or misfortune with injuries.

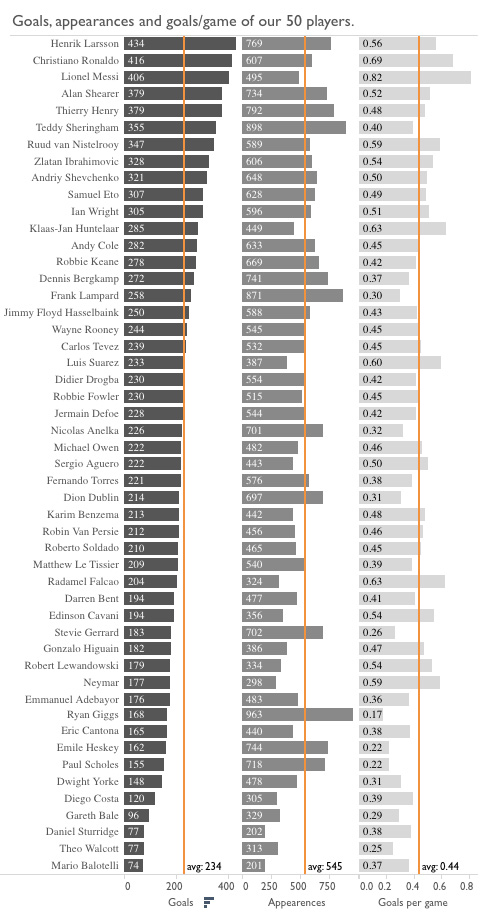

Taking data from Wikipedia, we looked at 50 of the most accomplished strikers and goalscoring midfielders of the past twenty years, taking as a starting point the 24 players to have scored over 100 Premier League goals (which admittedly contains Emile Heskey), and adding a further 26 elite current players in the the major European leagues, including Lionel Messi, Zlatan Ibrahimović, Neymar and Diego Costa. Some of the goalscorers are still playing, others have retired.

Very few of the 50 were hugely prolific before reaching their 20s, with the Brazilian Neymar the only one to clearly fit, albeit achieved in his native league – which, due to the mass exodus of its best talents, is not considered on a par with the major European leagues (even if Brazil still retains the cachet of the world’s most glamorous footballing nation). And of course, some included lots of penalties while others never got to take them.

But what, on average, can we tell from early-career promise? How important is youth vs experience? Where goals against easier opposition ? And what are the peak ages for goalscoring?

Youth vs Experience

Only seven of the 50 players were less prolific in their early 20s than they had been during their late teens: Neymar, Owen, Cavani, Bale, Defoe, Anelka and Robbie Keane, with two – Emile Heskey and Robin van Persie – showing no change. (A further two players had not registered a goal in professional football by the age of 21: Ian Wright and Didier Drogba). So 39 of the 50 were more prolific having just entered their twenties.Some may simply have failed to score goals in their teens, which makes it easier to beat a total of zero.

But if they didn’t even play during their teens that’s also evidence for slightly late blooming. Having said that, only four of the 50 fit this category: Radamel Falcao, Dion Dublin, and once again, Ian Wright and Didier Drogba. (If the player turned 20 during the season then he is listed as being 20 for that campaign.)At the age of 22/23, just eight strikers were less prolific than in their teens. One of these, Jermain Defoe, had racked up a lot of goals on loan at lower league Bournemouth in his teens, but wasn’t yet a fully established top-class Premier League striker.

Another, Neymar, had 42- and 43-goal seasons in Brazil, which was never going to be easily replicated in a side that already contained Lionel Messi, who, as well as being the focal point of Barcelona’s attack, also takes the penalties and free-kicks. But most players were more prolific at 22/23 than they had been at 18/19.Indeed, Messi is the prime example, as a player who didn’t score that many in his teens (just 19 in total, with some of those in Barcelona’s B and C teams), and was still fairly average as a goalscorer at 20 and 21, when his totals in all competitions were still falling below 20. Of course, he played a lot of his early football out wide, like the other major late-blooming goalscorer, Cristiano Ronaldo.The Portuguese didn’t start scoring more than 25+ in a season until aged 23 – up to the age of 22 his best season was 12 goals – and, to date, has peaked aged 27, with 60 goals in a single season (although he remains as prolific now in terms of goals per game).The clear star at 20/21 was Robbie Fowler. It’s easy to forget just how good he was in the mid-‘90s. He had almost four times the average number of goals you’d expect at that age when compared against his teenage tally, but by 22/23 he was only fractionally above average when compared against his tally aged 18/19.

In terms of the average number of goals scored for his age, Fowler was above average for the first four seasons in his career, and then, as injuries took their toll, below average for the remainder of it.

Easy Goals?

Going back to Defoe, he, like Messi, was one of approximately half the players whose teenage goals included those scored in lower leagues, either on loan, in B or C teams, or simply starting out on a lower rung of the ladder.This perhaps skews the data, because players like Ryan Giggs, Nicolas Anelka and Michael Owen were too good at 17 to be sent out on loan, but equally, at that age, were never going to score tons of goals (30 or more) in the top division.On the flip side, if they were loaned out to struggling third-tier sides, would they have scored more than they did playing for England’s three biggest clubs at the time?

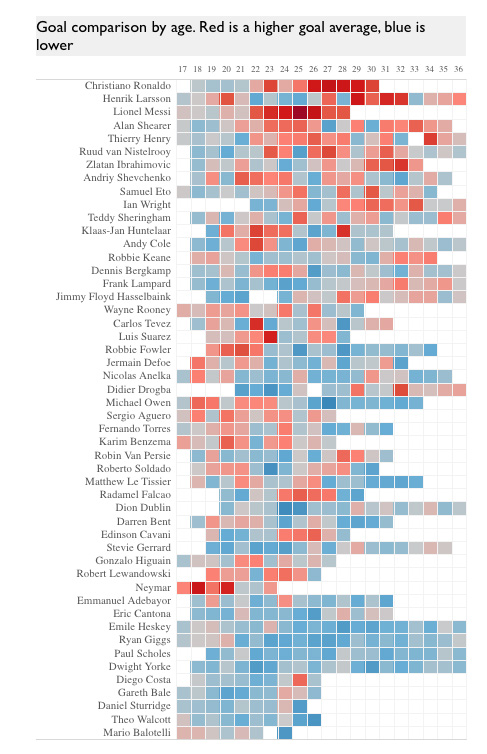

Comparison by Age

The heat-map below – displaying the players with the most club career goals in descending order – shows some interesting patterns. The top 10, from Cristiano Ronaldo down to Ian Wright, shows a sparse scattering of hot areas up to an including the age of 20 (the first four columns), with most either a cold blue (not very prolific) or a blank white (didn’t even play). The only two red rectangles of note are Henrik Larsson and Andriy Shevchenko, both in relatively minor leagues. It’s strange to think that Ruud van Nistelrooy wasn’t even very prolific as a teenager in the lower Dutch divisions.

Then, halfway down the full heatmap, there’s suddenly a whole raft of early-scorers: Rooney, Tevez, Fowler, Defoe, Anelka, Owen, Aguero, Benzema, van Persie and Soldado. Some of these players are still actively scoring goals. However, plenty of these, whether still playing or not, peaked early. It’s probably worth noting that Messi’s 73-goal season sets a very high benchmark, that makes Aguero’s 23 goals last season look fairly lukewarm. Indeed, the scoring exploits of Ronaldo and Messi have redefined what it means to be prolific.

The foot of the table, starting just below Neymar, comprises mostly ‘cold’ players who never had remarkable seasons but scored over 100 Premier League goals, or strikers aged 24-26, who have good seasons but, as yet, not a great total tally.

Very few players scored consistently well over their entire career. Many can be seen getting better, many can be seen getting worse, and many can be seen posting fairly average totals year after year. Only Messi and Ronaldo have remained consistently hot since turning into very prolific players, but of course they were slow starters. All of the other big scorers had fallow periods, perhaps due to injury.

Easy Eredivisie?

The biggest improvement between the ages of 19 and 23 can be seen in Klaas-Jan Huntelaar, who didn’t score a single goal in his 11 games as a teenager, then exploded into life, with 76 goals in the next three years. They of course came in the Dutch Eredivisie, which seems the easiest of Europe’s major leagues in which to score, particularly when compared with those who don’t play for the dominant teams in England or Spain.Having said that, the prolific Eredivisie players included in this 50-player study were able to replicate, to a fairly strong degree, their scoring feats in other major leagues:Huntelaar finding success in Germany, while van Persie, van Nistelrooy and Suarez all became big scorers in England. Meanwhile Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink, who only ever played in the second tier of Dutch football, scored all but five of his 250 goals outside his adoptive Holland.Perhaps the only player included who was prolific only in weaker leagues is Henrik Larsson, who was a fine player, but who had an unremarkable record at Barcelona and (briefly) Manchester United, and merely a decent one in Dutch football.

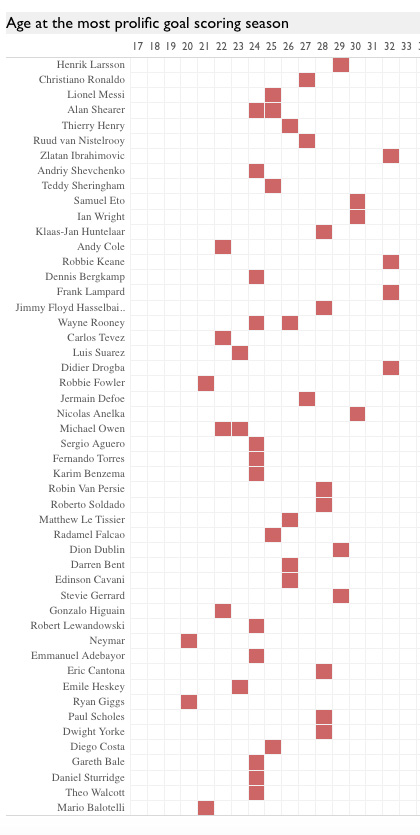

The Peak Age

From the data, 24 is the peak age for goalscoring in terms of pure numbers, particularly when looking at individuals’ best seasons. Seven of the 50 players had their most prolific season in their 30s, while none of the 50 did so in their teens.Almost half of the players could still theoretically have their best season in their 30s, with four of the players still not even 25 yet. Three players duplicated their best total in two different seasons, meaning that there are in fact 53 ‘best season’ markers.Just two players had their best season aged 20, and just two more did so aged 21. Four more peaked at 22, and three others peaked at 23, although one of these was Michael Owen, who netted 28 in all competitions two seasons in a row, so he’s included in the 22 and the 23 figures.That makes a total of just 11 out of 53 – 20.7% – at their most prolific before the age of 24.

Remarkably, 12 players peaked at 24; meaning that, by this measure, 24 was a more reliable age for players’ peaking than 16-23 combined.

People often talk of a players’ peak years being from 27 to 31, when they have the experience to read the game and have yet to lose their pace. But logic suggests that goalkeepers and centre-backs peak later than strikers, who often become ineffective when they lose their pace.Looking at the data, it’s clear that anyone who is 28, and who therefore still commands a massive fee (as prices tend to drop only at 29/30), should be treated with caution. The notion that you’re buying a ready-made star at 28 is countered with the fact that you may be paying for their past, not their future; they come with no greater guarantees once they pass 28 than buying a 20-year-old, who, all being well, also possesses the chance to play for the club for over a decade or command a high sell-on fee.In terms of the sheer quantity of goals, 24-year-olds lead the way, but then, as previously mentioned, there are a greater number of players at that age included in the study, given that a few are still only in their mid-20s. Even so, it’s then a massive drop at 25 from 24, with 27 the last age where a high quantity of goals is recorded. There seems to be little difference between the age bands of 22, 28, 30 and 32.

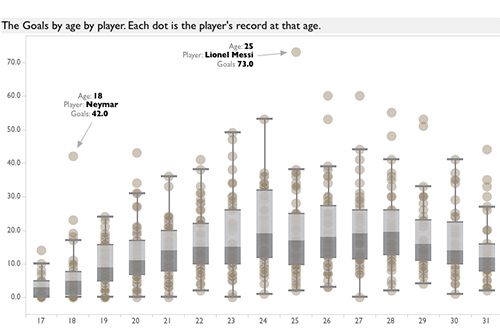

Goals Per Game

Goals per game, shown in the box plots below, tells a slightly different story, although it also sees a sharp decline after the age of 28. This measure is unaffected by the inclusion of players who have yet to finish their careers, as goals per game is an average rather than an absolute total.Here the peak is 28, before a massive drop at the age of 29, with one of the two outlying 29-year-olds being Henrik Larsson, whose goals for Celtic were “easier” given the relatively poor quality of Scottish football by that time. There are eight 28-year-olds with a season-strike rate better than 0.7 goals per game, but only two 29-year-olds, and three 30-year-olds.There’s a slight rise in the number when players head towards their mid-30s, but by this stage a lot of strikers aren’t playing every game; certainly Michael Owen’s inclusion, at the age of 32, is due to three goals from just four games for Manchester United that season. (It was actually Owen’s best season for goals-per-game.)

The median average of goals per game – the dark grey box – would show a gradual decline after the age of 27 (where it peaks) but for the outlier of Thierry Henry at the age of 34, who helps buck the trend after five successive drops in marksmanship per age group; while Henry, who played in the weaker American league, joins Drogba, who scored goals in China, in inflating the average effectiveness of 35-year-olds.Indeed, Henrik Larsson (by then back in the weak Swedish league), completes the top three for goals per game at that age. Alan Shearer, with 0.34 goals per game, is the only 35-year-old playing in the top division of a top league, out of the 50 sampled.

Conclusion

While limited to only 50 players, the data clearly shows that those who are regarded as elite goalscorers develop at very different rates. A fast start to a career can lead to serious injuries and burnout, and a relatively slow start does not mean that players cannot go on to become great goalscorers – indeed, many of the very best weren’t especially prolific until they were 22.To put it another way, some are hares, some are tortoises.Almost all of the 50 had low-scoring seasons at some point, for one reason or another.

Overall, the best age seems to be 24, but as with any footballer, a lot depends on the individual in question.