By Mihail Vladimirov.

Summary:

- Palace started with a higher defensive line, but with no pressing, trying to win the ball in the midfield third, as well as protect from being pinned back deep in their half.

- Because Liverpool started with the diamond, and dominated possession, whenever they lost the ball their two full-backs left them exposed out wide, and Palace took full advantage of this weakness.

- After the opening goal, the away team failed to replicate the same movement and creativity to exploit the Eagles’ passive initial approach.

- Instead, the Reds maintained sterile possession, without ever being able to up the tempo, or move forward as a passing unit.

- Rodgers switched to the 4-2-1-3 at the start of the second half, improving the passing options, the defensive structure but still lacking an extra midfield runner off-the-ball.

- Furthermore, the full-backs now stayed deeper, which again restricted the team going forward.

- Once again, Rodgers’ in-game substitutions failed to influence the match.

Formation and Team News:

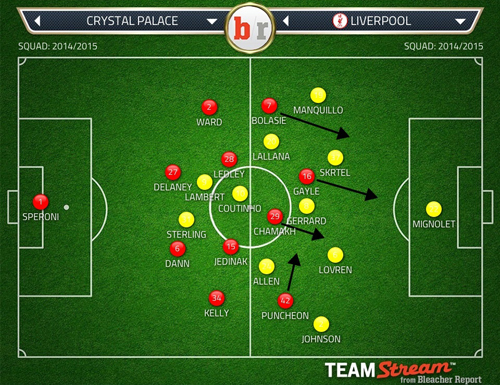

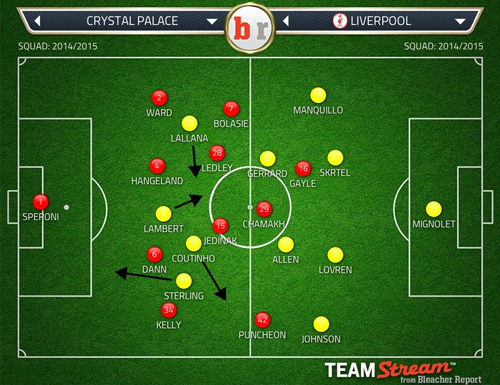

Warnock’s formation and starting XI was as expected. Palace continued with the recent 4-4-1-1 variant with the only surprise being Gayle starting instead of Campbell up front.

For Liverpool, the absence of Balotelli and Henderson caused some selection issues. Rodgers came up with the solution to change the formation to a 4-diamond-2, using Allen and Lallana as the shuttlers either side of Gerrard with Coutinho in the hole behind the front pair of Sterling and Lambert.

Palace passive and counter-attacking oriented

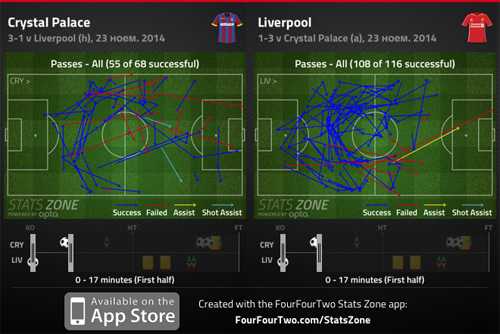

Warnock’s side didn’t surprise in terms of initial approach either. They started the game in a passive mode, obviously looking to concede possession in favour of luring Liverpool forward to exploit the vacated space on the break.

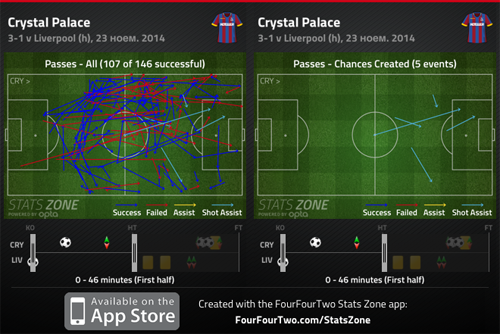

What was interesting though was that their out of possession strategy surprisingly involved keeping a relatively high defensive line. Right from the start, it was clear the home team tried to push up and compress the space towards the midfield zone, even if there was no clear sign of them wanting to put pressure on the ball or apply even a half-hearted zonal pressing. It was if their aim was to simply prevent being too easily pinned back deep in their half, instead preferring to force the game being played more around the midfield third from where they hoped the compressed space would lead to possession turnovers and potential opportunities to break forward dangerously.

To achieve this it was clear the back four pushed up, while the front pair looked determined to position themselves in the space between Liverpool’s back three (created when Gerrard dropped towards the centre-backs) and the midfield unit. This meant Jedinak and Ledley patrolled a much smaller zone through the middle.

However, the downside of this approach (high defensive line, no pressure on the ball and rather slower centre-backs) was clear too – the theoretical vulnerability of through balls sending a runner breaking in behind. This is precisely what happened in the 90th second of the game when Lallana lofted a superb pass for Lambert to get in behind Kelly, control the ball, and place it into the back of the net. Apart from conceding the goal though, Palace’s vulnerable defensive strategy wasn’t exploited any further. Partially, this was because of how well the team worked well as a unit to compress the space towards the midfield zone – the defence pushed up, the attack dropped deep. However, in large part, it was because of Liverpool’s inability to find ways to exploit it as they did for their goal (more on this later).

In attack, the home team’s plan was very simple. They looked happy to concede possession – but ensure the opposition will be passing from their defensive third in a rather sterile manner – in exchange for luring Liverpool to spread their team in attack and leave space in behind. The fact Liverpool started the game with the diamond formation further played into Palace’s hands. This was because as Liverpool had more of the ball, the full-backs had to push up to provide the width, which in turn meant there is plenty of space in behind them down the channels – precisely the space Warnock’s side usually targets on the break.

Interestingly, even being a goal down did not really change Palace’s behaviour. They didn’t start to press more or look more aggressive in their ball-winning activities. They remained similarly passive as they had from the start, focusing on compressing the space towards the midfield zone and simply waiting for possession turnovers and suitable chances to counter-attack. As such, as much we can say Liverpool’s opening goal was caused by Palace’s approach, the home team’s equaliser had more to do with the weaknesses of Liverpool.

The combination of the 4-diamond-2’s inherent weaknesses down the flanks and having Gerrard as the deepest in midfield meant Liverpool were as vulnerable on the break as Palace were when Liverpool had the ball. Eventually this proved to be Liverpool’s undoing once again. A simple possession turnover caught Liverpool completely off guard with a series of positional errors, following their inherent structural and personnel weaknesses, leading to Palace’s equaliser. This was a similar theme throughout the first half: Gerrard was continually struggling to protect the space between the lines. The full-backs struggled to deal 2-v-1 on the flanks. Allen and Lallana looked confused about whether they needed to press Palace’s midfield pair or track back with Palace’s in-cutting wingers. Furthermore, all of these issues contributed to leaving the centre-backs badly exposed, which in turn led to poor positional play. As a result, Liverpool’s defensive shape was dreadful with the players not working as a unit or with the required organisation and understanding of how exactly to deal with the threat posed by Palace on the break.

Going forward the home team paid more attention down the left-hand side. This was a logical result following how often Puncheon drifted infield while Bolasie remained wider, keener to pick up the ball and run powerfully with it. The former played a few dangerous balls from his narrow position to set up a teammate bursting forward to continue a counter attack; while the later was continually fed with the ball to have a go at Manquillo or exploit the space in behind Gerrard.

Liverpool lacking potency in attack

The game started brilliantly for Liverpool with their early goal putting them in a commanding position. The context suited them perfectly in that if Palace were to remain passive, the team could exploit their high defensive line, no pressure on the ball and slow centre-backs in a similar way to the goal. Then if Palace were to push on and commit more bodies forward, they would be simply even more space for Liverpool to target on the break. It looked like a win-win situation for the Reds.

However, in reality neither happened which was mainly because of Liverpool’s poor play in terms of passing and movement. The visitors reacted to getting ahead so early by visibly wanting to simply keep the ball and lure the opposition to come at them. It felt very much like the approach Rodgers had at Swansea – deep ball retention aiming to draw the opposition higher up before the front players were being fed on the run with balls coming from deep into the vacated space. This didn’t happen for the following reasons.

Palace looked like happy to continue with their initial approach of remaining passive, looking to squeeze the play towards the midfield zone and simply waiting for counter-attacking chances. This suited Liverpool in that the visitors had an easy time on the ball and given the result there was no need to push forward and attack en masse. In that scenario it would have been expected that the Reds continued to simply keep the ball and wait for suitable chance to feed someone in behind, much as they did for the opening goal.

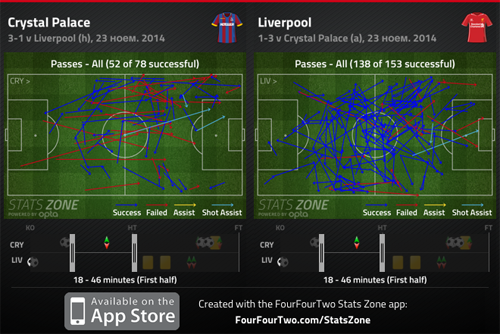

The problem though was twofold. On the one hand, Liverpool’s passing looked incredibly sluggish, lacking any kind of tempo and purpose. Sure, Palace’s positioning and the way they compressed the space in the midfield zone was good, but this doesn’t fully explain how Liverpool couldn’t use their numerical advantage and possession better. The ball was moving slowly across the pitch, there wasn’t really any pace or purpose. On the other hand, the visitors’ starting XI was full of ball-players but little else. There were plenty of players capable to join during the build-up play and pass the ball around. Nevertheless, there were not enough players capable to provide the required off-the-ball movement. Sterling was the only one capable to provide that sudden burst of pace to latch onto a through ball. Additionally, the fact he was played as a striker further limited the team’s ability to offer the required level of movement. Given Palace’s high defensive line it was logical that his advanced position was a potential threat, but the team’s inability to quickly move the ball forward and feed him with similar passes to the one with which Lallana released Lambert for the goal simply meant he was not useful in that position.

Therefore, not only were Liverpool enjoying what clearly was sterile possession, but they didn’t have the right tools to either threaten more often with direct attacks – as they did for the first goal – or initially push forward as a unit and take it from there in a more gradual way. What was also interesting was that for all their numerical advantage in midfield and the presence of so many ball-players, the visitors looked unable to morph the deep passing higher up, retain the ball in the final third, and use the possession as a means of penetration.

This is linked to the lack of players making forward runs and asking for the ball in advanced areas. Basically all of the midfielders were dropping deep to pick up the ball, which left Sterling and Lambert isolated – so the two of them also had to follow suit and start to drop deep. As a result, it meant Liverpool had no forward pass, as their whole team was continually moving towards their own goal.

As discussed before, this isn’t necessarily a problem per se if after the initial wave of dropping deep, they turn around and start gradually moving forward by methodically exchanging the ball and gaining territory. But as per usual, this is not what Liverpool showed. Either the whole team were dropping deep but then didn’t really succeed to turn around and move forward gradually; or the team became broken with the midfielders dropping, the forwards staying ahead and no-one making the reverse movement to connect the side and offer the in-between passing options.

After Palace’s equaliser, Liverpool reacted well by trying to push forward more and in greater numbers, resulting in a few interesting and a sharper attacking moves being created. However, although the team succeeded moving the play higher up the pitch, the lack of extra firepower due to not enough players making the complimentary off-the-ball movement still negatively impacted on the team. There was simply not enough movement variation across the team, with the midfield quartet all seeking to play the ball and not run ahead of the play, while the front two were easily crowded out.

On top of Liverpool’s attacking lack of potency, the Palace now had more chances to fulfil their plan to threat on the break. The more Liverpool had possession and tried to push forward, the more space they left for their opposition. Every time the ball was regained by the home, team was a dangerous situation with Bolasie in particular being a constant menace down the left.

With Liverpool not really finding any joy in attack and in addition being inherently vulnerable defensively, arguably there was a clear need for a first half change in the formation. The problem though was that given the starting XI – and no Henderson or Can – the potential options were hugely limited. Arguably, the only two variants were to either see a change towards a 4-1-2-3 or go for a 4-2-1-3. The former could have meant a similar defensive vulnerability, as Allen and Coutinho ahead of Gerrard wouldn’t have been able to provide the required midfield stability. At least Lallana and Sterling flanking Lambert could have resulted in a much more fluid attacking unit, with a greater number of movement permutations and as a result a bigger attacking threat.

The former variant – switching to a 4-2-1-3 – should have been able to combine a better defensive solidity and more variations in attack. With Allen sitting next to Gerrard, the space between the lines would have been better protected, whereas the front four – supported by the overlapping full-backs – would have been able to offer a greater range of movement interplay and passing fluency. Then, with Coutinho and Lallana roaming around to link-up the play, Sterling and Lambert are free to combine off-the-ball in a way to exploit the gaps left around and in behind Palace’s defence.

At the very least, given how obvious it was that Bolasie was the main attacking outlet for Palace, something needed to be done on that front. If there was not going to be any change in the formation, then Allen and Lallana could have been swapped with the former now put on the right to try to help Manquillo deal with Bolasie. This would have leave Lallana on the left – closer to Sterling – that might have led to better attacking link-up and more interplay on and off-the-ball over that side.

Start of second half – Rodgers switch to 4-2-1-3

At half-time, Rodgers switched his formation. Liverpool returned to the pitch in more of a 4-2-1-3 shape, with Allen now joining Gerrard, Sterling pushed to the left flank and Lallana on the right with Coutinho in the hole. Presumably, this was Rodgers’ attempt to address the apparent defensive weaknesses down the flanks and through the middle, on top of trying to mprove the diversity of his team in attack.

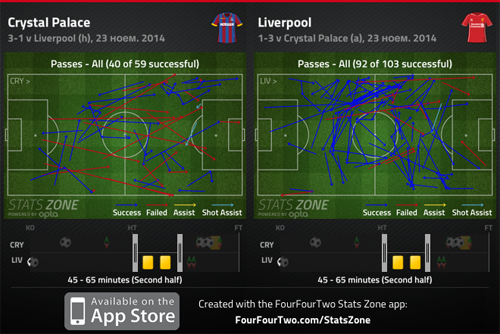

Immediatelly, Liverpool improved, now looking much more solid and stable defensively and a lot more fluid going forward.

First, Palace’s 2-v-1 advantage down the flanks wasn’t there anymore. With Sterling and Lallana now playing wide, the visitors looked far more secure during the defensive transitions, as the two of them helped close down to delay the oppositions counter-attacks or simply dropped back to offer support to their full-backs. Then with Allen now alongside Gerrard the space between the lines was better protected. Additionally, both full-backs appeared more restricted in their forward runs, which was potentially supposed to prevent Palace’s wide men being as influential on the break as in the first half.

Going forward, it appeared Gerrard was more free to step out and join the team’s attacking moves. A couple of times he surged forward from deep dangerously, even if his shots ended up off target. This and how team spread out in the new 4-2-1-3 formation simply meant there were more and better pass and move angles available for the players. Coutinho was often drifting wide towards the left, allowing Sterling to make the reverse movement. With Lallana going infield off the right and Gerrard stepping out from deep, the ball circulation gained greater speed and purpose, as the team now showed greater movement fluidity, which in turn opened up extra passing options (which had previously been missing). The ball started to move forward in a quicker and crisper way, the players interplayed better all over the pitch.

In short, the better space coverage and greater defensive stability (provided by a partner to Gerrard and the restricted full-backs) looked to largely halt Palace’s threat on the break. Meanwhile, there was much better potency going forward in terms of how the ball was passed around and how the players related to each other in terms of movement.

What was missing though was that extra firepower in terms of a third off-the-ball runner to further stretch the opposition and allow for greater attacking sophistication. For all their improvement in attack, Liverpool couldn’t really open up Palace at all. Apart from missing that third penetrator, the restriction of the full-backs, as much as it was useful from a defensive point of view, further limited the team in attack. The two of them largely stayed in line with the midfield pair, sporadically getting ahead of the ball in the rare situations the ball retention process was long enough to successfully pin back Palace deep in their half. This looked to make Liverpool like a broken side with a back six and a front four.

As mentioned already, this was good as it made Liverpool much more stable defensively but it still hampered the team offensively. In such a scenario – where the team is intentionally broken for defensive reasons (due to Gerrard’s defensive shortcomings it was a case of the full-backs restricted to provide the required defensive cover) – the emphasis is on the front four to largely play on their own in attack. Then, they will only recievesporadic support from the full-backs and/or one of the midfielders occassionally stepping forward.

The main problem was Liverpool’s front four of Coutinho, Lallana, Sterling and Lambert didn’t have the required tactical potential to be able to do so. Again, this was to do with the mis-match of players looking to drop in and/or play the ball vs players willing to provide the off-the-ball threat. Coutinho and Lallana were roaming around, which was required in order to link-up play with the back six. But with Lambert also dropping deep and looking to roam around, it was only Sterling capable to provide the threat in terms of decisive runs.

Another problem was that given the supposedly deliberate broken nature of the team, the front four had to provide all the attacking aspects – playmaking presence, width to stretch the play and off-ball diversity – but couldn’t due to the limitations of the selected personnel. In that scenario, Rodgers needed to introduce players off the bench to help provide the whole range of the required tactical aspects. Borini could have come in to play off the left, moving Sterling on the right. The two of them could have provided the required extra off-the-ball support to Lambert and run beyond him in addition to Sterling being able to mix up his attacking approach and stay wide to provide the width from time to time. This would leave Coutinho as the central playmaker.

The alternative variant was to see a change to a 4-1-2-3. Arguably, this was going to be the more suitable decision as with Lucas in for Gerrard the team would have a holding midfielder who can actually protect the centre-backs and create a back three unit who can cover the width of the pitch. This would have allowed the full-backs to push forward (with the possibility of seeing Moreno in for Johnson) and influence the play in the final third, allowing the wide men (either Sterling and Lallana or Sterling and Borini) to play narrower and be closer to Lambert, while the midfield pair offer the passing platform to provide the creativity (Coutinho and Allen).

Liverpool’s subs and Palace’s goals

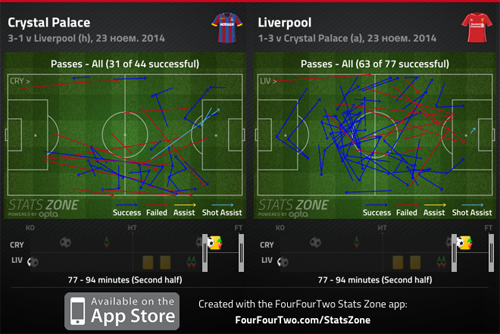

Around the hour mark, Liverpool’s initial spark at the start of the second half started to fade away. This was used by the home team, who in turn started to boss the play, continually roaring forward at every opportunity, looking dangerous every time they had chance to run at Liverpool on the break.

With Liverpool losing their dominance and starting to be put under more and more pressure, Rodgers could have reacted somehow and helped put his team back in the driving seat. Although his changes, once again, were unnecessarily delayed, it could at least be said that they made partial sense. The Borini for Lallana change was sensible in that it introduced a player to slot next to Lambert and provide the extra off-the-ball support, while leaving Sterling on the right to provide extra width. The Can for Allen change seemed peculiar in that it didn’t change anything tactically, on top of removing one of the best performing players. Still, the main reason might have been the head injury Allen got early in the first half and the fact his bleeding couldn’t be fully stopped. Then with Coutinho as per usual showing signs of tiredness and fading away in the last 20-25 minutes of the games, it was strange to see Rodgers not using his third sub at all. The Brazilian’s influence drastically diminished in the latter stage of the game and it was clear he was ineffectual and not really helping his team. Arguably, Borini could have replaced him or at the very least, the third sub could have seen Markovic coming in for Coutinho and have the Serbian and Sterling running down the flanks with Borini and Lambert complementing each other in attack.

Anyway, for all the arguable potential benefits and negatives of how exactly Rodgers used or didn’t use his bench, Liverpool actually went to push forward once more, creating a couple of decent attacking moves. Then, when it seemed the visitors were picking up attacking momentum, the combination of a lack of overall organisation for set-piece situations (this time a throw-in), plus another series of poor individual defensive reactions led to Palace scoring their second goal. Liverpool couldn’t even launch a comeback as only a couple of minute’s later Palace scored their third goal from a direct free-kick, which logically sealed the game in their favour. It was a game over for Liverpool.

The period after Palace’s goals saw Liverpool revert to their previous level of lacking any kind of creativity or passing vibrancy, unable to organise a late push and struggling to morph the deep possession into something sustainable in the final third. The series of long passes aimed forward was easy for Palace’s defence to handle and clear away. As a result, the home team comfortably saw out the game.

Post-match thoughts

This game saw the same old issues from Liverpool. The questionable starting selection contributed to lack of defensive organisation and ineffective attack, followed by in the mainly poor in-game management and inability to tactically influence the game decisively enough.

As for Palace – their approach was simple but efficient and they executed it well enough to take advantage of Liverpool’s weak spots to eventually fully deserve the win.