By Paul Tomkins.

First of all, let me state that, beyond the tense rivalries of recent years, I harbour no grudge with Chelsea Football Club per se. Let me be clear: I am fully aware that it could just as easily have been Liverpool FC that Roman Abramovich purchased in 2003, and then, like any fan, I’d have enjoyed the decade of undoubted success that would have followed.

Back in 2003, neither Liverpool nor Chelsea were geared towards great success. Both clubs were outside the top three (4th and 5th) and well off the pace, managed by good but not exceptional bosses. Neither club was getting close to the £30m Manchester United had already spent on a single player; at the time, Chelsea and Liverpool could spend around £15m tops. That’s how much the Russian oligarch changed things.

In going through the Premier League’s entire transfer history, with inflation applied, it struck me just how massive Chelsea’s investment was a decade ago, and how, in real terms, it dwarfs even Man City’s outlay.

On top of studying the way the game changed with Abramovich’s money, this article will also look at the immediate boost that a sharp rise in spending can give a club.

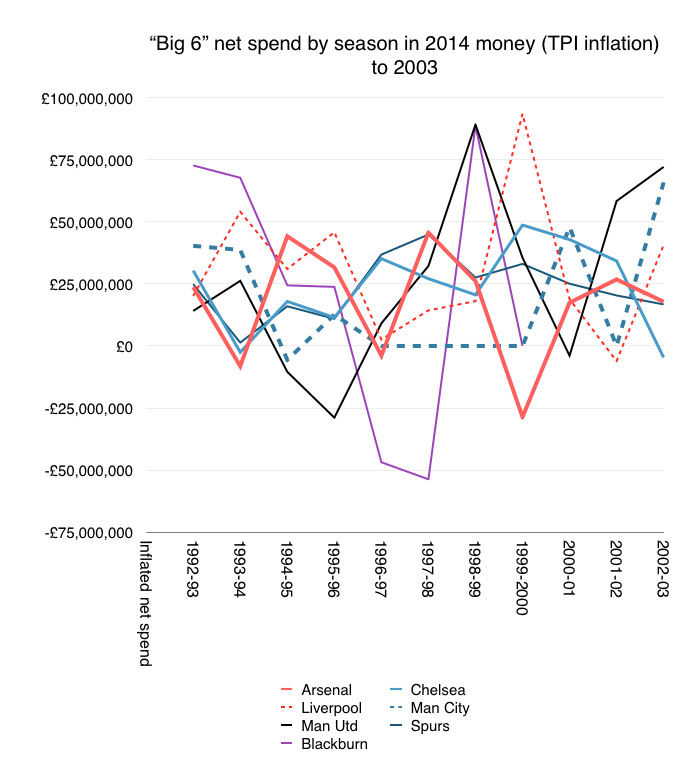

But first of all, look at how the Premier League’s ‘big six’ were spending in the decade before things went all Roman. Man City were a very sleepy giant at the time, having recent spent several years away from the top flight, but they still had the 2nd-highest inflated net spend (out of the big six) in 2002/03, and the highest net spend (of the six) a decade earlier, when the new format was introduced.

Otherwise, in today’s money, all six clubs are within a maximum of +£100m and -£30m net spend over that eleven season period. United have a couple of spikes, and Liverpool hit the highest overall spend of that period in 1999/00. As well as spending, United and Arsenal each have a season of £25m profit. All in all, nothing too dramatic.

How Chelsea Ruined Football: Transfer Spend

Unlike wage bills, which are commitments over a number of seasons, any given club’s transfer spending wildly fluctuates from one year to the next. Some years a club will spend £100m, the next year they’ll spend £1m; but they don’t become 100 times worse. However, much of what we’ve been doing for five years now with the Transfer Price Index is showing that, like wages, transfer spending can be used to measure expectations. It doesn’t mean a team will perform exactly to the model, or that any given big signing will succeed, but overall, things average out and, most of the time, the cream rises to the top.

Big transfer spends tend to lead to positive outcomes for two reasons. First, they are part of the stockpiling of players, so that the manager has greater choice and an increased number of insurance policies to cover injuries, fatigue and loss of form; and second, a summer of high-investment can add impetus to an impending season. (First, because there’s more talent, and second, the psychological boost it can give to players and fans alike.)

A high turnover can of course be counterproductive, as Spurs discovered last year, although that was still a low net spend; they lost their best player and failed to replace the impact he could make with over half a dozen signings. (But they still have those players, and there’s nothing to say that two or three of them, at least, can’t come good. Maybe they all will, or maybe none will. But the law of averages suggests that some of those players with good pedigree, such as Érik Lamela, can succeed.)

But as I’ve argued for a few years now, net spend falls down because it relies on a starting point: i.e. net spend since …. And we can all pick and choose arbitrary starting (and ending) points that suit our argument. What if you pick a year to start measuring net spend after one club has just had seen its biggest ever outlay? It will have all those resources, and they’ll be excluded from your calculations.

Net spend is a better measurement than gross spend, which is very misleading, but even net spending doesn’t tell the true story. (For an example of the misleading nature of gross spending, look at Southampton: they’ve bought a couple of players, Tadic and Pellé, who have cost around £20m in total. Yet they’ve sold five players for almost £100m.)

Using our TPI inflation model, we look at the cost of talent that makes it onto the pitch. The cost of the team, and the squad, once inflation is applied, is where all that spending (and selling) led to. They key to making judgements is what each club has at its disposal in any given season, not what it paid (or made) on players no longer at the club.

Case Study

Something struck me in the preparation for this piece. How much did Alex Ferguson spend on central midfielders in 26 years at Manchester United? When including players who ended up playing in the position beyond one-off matches (such as Alan Smith and Phil Jones), in today’s money it’s almost £400m for 20 players, or an average of £18m each. And yet how many were really successful?

I’d say … two. Most neutrals would say that Roy Keane and Paul Ince made a big difference at Old Trafford. But we don’t judge Alex Ferguson on his transfer record with central midfielders. Keane and Ince were fairly faultless signings, even if there were fallings out later in their time at United. Michael Carrick was clearly a very good buy, if not quite exceptional (and certainly not cheap in today’s money).

United’s story of central midfielders shows how “mega buys” like the undeniably talented Juan Sebastian Veron can fail; and yet two of the three most expensive central midfield purchases (in 2014 money) – Carrick and Keane – proved successful.

However, expand it out, and only three of the top eight (with time admittedly on Phil Jones’ side and reversion to centre-back likely) can be labelled good buys. Anderson, at £31m CTPP, was a disaster, and that’s being generous with his original transfer price (with reports that it was a lot more than the £18m we went with). Hargreaves, at £29m TPI, was a logical purchase that didn’t work out due to injury. And anyone who mocks Liverpool’s spending on Jordan Henderson needs to be aware that Kleberson cost roughly the same in today’s money, while Djemba Djemba’s fee is now £10m.

There are two points I’m making here. First: that individual big-fee transfers come with zero guarantees; and second: that spending needs to be assessed in terms of dealing with a collection of resources, and not as one-offs. So if we were to judge Ferguson on the arbitrary concept of buying central midfielders he’d look a bad manager, and we know that’s not the case. The context is that he inherited Bryan Robson. He helped blood Paul Scholes and Nicky Butt, plus David Beckham, who also had spells in the position. And some of his signings were unlucky with injury; it’s not all about good or bad judgement.

Ferguson often didn’t desperately need to buy central midfielders, and in some seasons he didn’t desperately need to buy anyone. If your team is complete, you don’t need to invest in it. Building a team usually costs more – in terms of transfer window outlay – than maintaining a team. So if you limit yourself to analysing net or gross spending from a certain point in time you may be comparing one club’s team building with another’s ticking over.

Spike

Having said that, success seems to spike shortly after high investment, but not always immediately; sometimes it’s a season later.

Going back to that earlier graph, the two biggest spikes are United in 1998/99 and Liverpool in 1999/00. United immediately experienced a much-improved season; indeed, the best in their history. It took Liverpool a bit longer, but in 2001 they became the first English club to win three different cup competitions in the same season; a season in which their net spend was very low, but where the players bought a year earlier, such as Hyypia, Henchoz, Westerveld and Hamann, were vital. Both clubs invested heavily and ended up winning trebles soon after.

Unless expensive players are retiring or being sold on the cheap, a high net spend in one season will almost certainly increase the cost of the squad, and most likely, the cost of the £XI (which is the average cost of the team over 38 games with inflation applied). That then increases their chances of success.

(Note: I’d like to further examine the spikes, or bounces, after high investment in a single season, but as with all the TPI stuff, there’s so much data and not enough time to do everything possible with it.)

Blackburn

The interesting example from the ‘90s is Blackburn, whose years before their premillennial relegation are added to the ‘big six’ graphs. They had a large net spend in 1992/93, which carried them to the title in 1995, by which time the spending had stopped. They then had two seasons of selling off their assets (mostly to Newcastle, in the form of Shearer and Batty), before Roy Hodgson arrived and oversaw a net spend almost 50% bigger than the one that led to the title. This is one of the few examples of a really high net spend (in comparison with other clubs in the era) leading, within months, to relegation. They remain the most expensive side relegated in the Premier League era. Clearly Hodgson needed to spend money, he just did so with a disastrous hit rate.

(Newcastle’s spending in the ‘90s was also fairly big, topping out at £74.5m in 1995/96, with two other seasons at +£50m, but unlike Liverpool, Man United and Blackburn, they never got close to the £100m mark.)

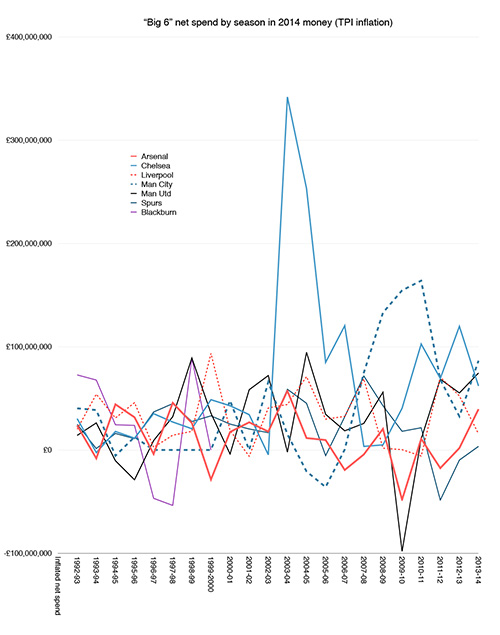

The earlier graph deals with the Premier League era’s first eleven seasons. Then came Chelsea. The graph below shows those same first eleven seasons, followed by the subsequent campaigns.

That, above, is the skyscraper built with Abramovich’s money; a giant dwarfing the rest of the Premier League. Looking at that, you’d have to say that the miracle would have been Chelsea not winning the league at that time. Following that investment, Chelsea were fielding the costliest side in the English game.

The two biggest net spends in the Premier League era, in terms of the percentage of money spent in a single season, belong to Chelsea, from around a decade ago. The next two highest net spends belong to Manchester City, from four and five years ago. Following these immense outlays, Chelsea won two titles in two years; City two titles in three years.

In 2014 money, no team before 2003 had ever spent over £100m net in a single season. Then Chelsea spent over £340m TPI. If anyone still doesn’t think that this was the turning point in English football’s arms race, they’re in denial.

Exceeding £100m net (TPI) in a single season has now happened seven times, split between just two clubs: Chelsea and Manchester City. The closest Manchester United have come is the £94m of 2004/05, whereas Liverpool’s peak remains £93m in 1999/00. In relative terms, United’s biggest spending under Ferguson occurred in the late ‘80s, but our data (which is hard enough to collate and manage) is limited to the cut-off point of 1992, for practical reasons.

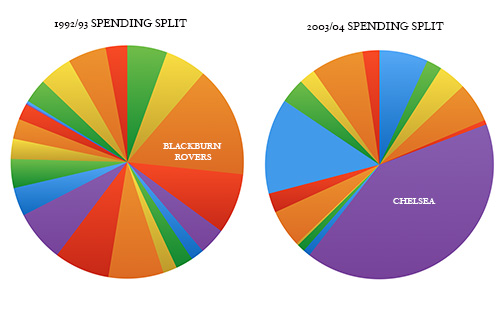

In 2003/04, Chelsea’s spending represented over forty percent of the top division’s total outlay. The year after, it was still seriously high, at 31.9%.

In 2009/10, Man City’s spending was 25.7% of the Premier League’s total outlay, and a year later, 28.3%.

To put it into context, in their biggest spending season on the way to the title, Blackburn topped out at just 15.4% of Premier League spending, albeit the only club to hit double figures in the rebranded league’s inaugural season. This is highlighted in the pie chart below.

Chelsea’s spending was clearly more extreme than City’s, and they also began from a higher starting point (they were already occasional qualifiers for the Champions League). By the time City were trying to join the party, Chelsea had an incredibly expensive side, so the Manchester club couldn’t change the landscape, merely add to it.

Chelsea had good players to sell between 2003 and 2005, as a result of overstocking, whereas just before the Sheikhs arrived, City were a mid-table club with precious few assets. What City proved was that, with fairly extreme investment, any club could leapfrog most of the competition.

Chelsea are now selling wisely, racking up big profits on what were signings at a good age: Juan Mata and David Luiz being prime examples. The stockpiling of youth/teen talent, before loaning out a couple of dozen promising players, is something I feel uneasy about, but at the same time it makes perfect sense under the rules.

This summer Chelsea have removed some high-value players (in TPI terms) from their squad, such as Frank Lampard and the aforementioned Luiz, but are adding players who cost £30m or more. Ditto Manchester United, who have released their most expensive TPI player (Rio Ferdinand), but are also adding at least two £30m players.

Accumulation

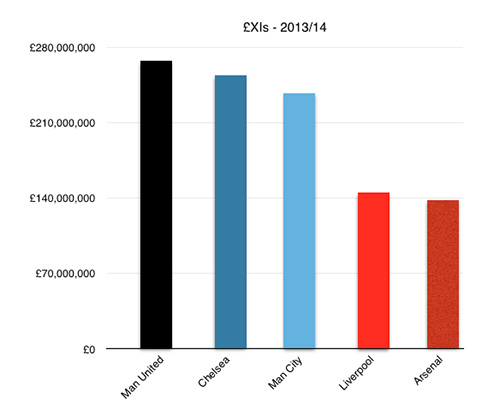

Whether you look at net or gross spending, either over a short or long period of time, the ultimate arbitrator is what talent a club can field at any given point: the aforementioned £XI.

Last season, three clubs led the way. Even with £70m Rio Ferdinand only starting 12 league games (his value therefore not counted in over two-thirds of the games), United still fielded more expensive XIs, on average, than Chelsea and City, albeit by very small margins. Two of these clubs had proven foreign managers, while the other dragged an expensive side down to Everton’s level (as a foreign manager dragged Everton up). The Moyes months will always be a dark part of United’s history, and yet you have to think that Van Gaal could get much more out of last season’s squad, even before additions are made. Despite all the differing levels of spending, all three clubs have ended up with teams costing a similar amount.

The cost of the XIs fielded by Liverpool and Arsenal are roughly half that of the big three. There’s a reason Arsenal now come 4th most seasons: that’s where their spending places them (unlike in 1998, for example, when they had the costliest £XI, believe it or not.) Once cup games are added, the squad is never deep enough to mount a serious, lasting title challenge. Sometimes they start well and tail off, other times they start poorly and end well, but they almost always revert to the predictions of the model.

In fairness, Liverpool were a fraction more expensive, but even so, finishing 2nd was a miracle on that budget. Perhaps European games would have exposed a thinner squad, although Champions League participation makes it easier to assemble a bigger squad.

When teams are evenly matched in terms of resources, as with the three über-rich giants, or with Liverpool and Arsenal (with Spurs only a short way behind), it becomes more about management, and exceeding the sum of the squad’s parts (or in Moyes’ case, not being able to get it to function at even 75% of its basic level).

This is where Rodgers did so brilliantly last season. He had a bold approach that was outside the parameters of what most managers would attempt. Moyes’ fear and safety-first policy inhibited United, so it was no great achievement to finish above them. But it was certainly an achievement to take City down to the wire, and also to finish above Chelsea.

This transfer window isn’t over, but the model suggests Liverpool will still field, at best, the 4th-costliest £XI next season, and maybe even the 5th, with Arsenal’s investment in Sanchez (a £35m player) and Liverpool’s loss of Suarez (a £29m TPI asset). So Rodgers will have his work cut out.

Or perhaps, in adding a £20m centre-back and a £20m winger, as well as the £16m-23m attacking midfielder Lallana, Liverpool will be able to maintain its £XI level. Then it comes down to whether or not those players can match or exceed their value, and if Rodgers can juggle his resources across a different type of challenge.

Conclusion

It would be nice if FFP could help close the gap between the super-rich, the fairly rich and the poor. Chelsea and Man City built their successful sides before the rule changes were announced; indeed, it probably led to the new laws. Once those clubs gained billionaire benefactors, the rest had to try and compete; they couldn’t just roll over and give up.

I found it interesting when the Guardian’s David Conn recently noted that ticket prices have risen by over 1,000% since 1988, given that transfer prices have also risen by over 1,000% in that time. In order to compete at the top, clubs need the best players that money can buy. And a lot of that money comes from the fans. The rise in TV money, and the rise in ticket prices, simply pays for the rise in transfer fees and wages.

No-one wants to spend £50 to watch Liverpool, but if a club already lagging behind in the off-field stakes (compared with Chelsea and City’s mega-rich owners, Arsenal’s stadium size and ticket prices, and United’s marketing machine) was then to make its match tickets much cheaper than all its rivals, it would only fall further behind.

That’s the catch-22. Fans (rightly) don’t want to spend stupid amounts on tickets, but if they’re going to the game because they’re passionate die-hards, they also don’t want to see eleven journeymen on low wages because the turnover is so small. Liverpool need to find ways to make more money, and clubs make money through their fans.

It’d be lovely if our game was more like the German model, but it’s different over there because they never let it get out of hand in the first place. Once it is out of hand it’s harder to rein in; the proverbial bolted horse, and all that. Even then, Bayern seem to be growing stronger by feeding off their closest rivals. Tickets are much cheaper, but they all keep it cheap, therefore no-one has an unfair advantage.

Once Chelsea had all that extra money through non-footballing sources (i.e. Russian oil), it guaranteed that other clubs would have to either get their own sugar daddy (City), or find ways to make more money through merchandising and ticketing.

So fans pay ever more, and players take home increasingly obscene wages. But we also get pissed off when our club won’t pay that extra £20k-a-week or £1m to secure some star’s signature, disassociating ourselves from how that money needs to be found. In that sense, Chelsea have helped drive up (or at least accelerate the rise in) transfer fees and wages, and therefore, ticket prices too.

But as I said at the start, I wouldn’t be complaining if it was Liverpool that Abramovich had bought, because like all fans, I’m a short-sighted hypocrite who, first and foremost, wants what’s best for his team, rather than the greater good of the game. In that sense we’re probably all as dumb as each other.