By Paul Tomkins.

The one thing we’re quick to forget is that the future of football is never written in stone. I too am not immune from using precedents as some kind of proof of future success. You can find handy guides, it is true, but no-one is ever correct in predicting what will happen until that thing goes ahead and happens.

The truth is that all teams need their best players. The truth is also that many teams have improved after selling their best players (particularly if it’s for a world-class fee). And the truth, as well, is that sometimes a team’s best players stop being their best players, sometimes for the short-term, and sometimes permanently.

Another truth is that the older players get the more they break down; there is no golden rule, but by 33 or 34, many have lost what it was that made them great, and by 40, none will be left standing. Time is always running out.

Which examples do you want? And how do you know which way it will play out?

The most recent example of what not to do is Spurs, but on paper, at least, they acquired some excellent players last summer. In theory, Érik Lamela perhaps even has the potential to be as good as Gareth Bale, and three or four of the other signings have time, and quality, on their side. Time guarantees nothing, of course. But until the world ends, or football self-combusts, there is always a next game, in which to make an impression.

You can sell at the right time, or sell at the wrong time. You can reinvest the money wisely or you can waste it. Your replacements might start slowly, or they may immediately sparkle. A year later that situation may be the same, or totally reversed.

I guess the key to selling Suarez comes down to one phenomenon I’ve been pondering for years. Is it better to have a world-class player who can win games ‘on his own’ (even though he never takes to the field without another ten players in his colours), or take a near-world-record fee and buy three, four or maybe five players who can improve other areas of your team and help you cope with extra games and injury crises. The right and wrong answer, as ever, can be plucked from the past. You can choose whatever option you want, based on biases or how you judge the level of liquid in a drinking receptacle.

The problem with the über-star is that he’s one single player, and therefore injury, loss of form and suspension (a big factor in Suarez’s case) can remove that magic at a stroke. And of course, you might also become over-reliant on him, or he may be too greedy, doing things for his own glory rather than the good of the team.

A weird thing people say is “without Player X’s goals, Team Y would have finished Zth”. But presumably if he was sold, and the money reinvested, there’d be other players to score the goals, and you wouldn’t be seeing daft calculations on how good teams are with only 10 starters every game. (Without fielding a goalkeeper each week, even Manchester City would get relegated.) You can only look at the games where the star in question didn’t start – where someone else took their place – and in that case, Liverpool have fared really well without Suarez, albeit over a dozen or so games, rather than the 40-60 a season contains (unless you’ve just bitten someone, then it drops by about 20%).

The problem with replacing the über-star with three or four players is that you might end up with some expensive substitutes who offer nothing to the XI. Squad depth can be handy – indeed, most managers swear they need it – but is an £80m player more useful than ten £8m players? As ever, this depends on who the £8m players are; Coutinhos or Aspases?

If only four out of ten £8m players were successful – the rough rule of thumb I work on – then what if the four worked out as well as Coutinho, Azpilicueta, Remy and Schneiderlin (who actually only cost Southampton around £1m)? On top of those four, two or three of the others may be merely mediocre (handy back-ups), and two or three total flops (on whom some money can be recouped), would that represent good business? A downside is that the wages of ten good players (average of £50,000 a week) probably outstrips the weekly pay-packet of one world-class talent (£200,000) by more than two-to-one.

Alternatively, you could spend £40m on a big name like Mesut Ozil, and get a so-so season, and £40m on Robinho (which is what Manchester City paid, converted to 2014 money), and end up with little or no improvement. You can do this with examples good and bad: there are plenty to choose from, even in the £40m bracket. (In 2014 money, this is what Emile Heksey cost. Ditto Djibril Cissé.)

Maybe this season Ozil will prove to be a wise investment. Hopefully, at £25m, Adam Lallana will be able to play as confidently and imaginatively as he did in the lower pressure environment of Southampton, where he carried no big fee on his shoulders. Does he have the character to carry all that? I hope so. Can he replace some of the work-rate and creativity of Luis Suarez? Hopefully so. But until it happens, we can’t say for sure. We can talk about ability, potential, but never definites.

If you want easy answers, look away.

If you study Liverpool’s spending in the wake of the Torres sale, you can say that Andy Carroll, despite some potential, proved a fairly disastrous buy; but Suarez elevated the side and, if he is sold, would generate a massive profit. Then think about the two big buys of the summer of 2011: Stewart Downing and Jordan Henderson. Neither convinced initially, and Downing was sold (even if he was never quite as bad as people made out or as good as could have been had he had a bit more self-belief), but now Henderson is a key component of the side. This might be getting back to Tomkins Law (© Dan Kennett) of a 40-50% success rate, but it’s not merely making the case about half the deals working, but that in 2012 or even 2013 most people would have told you that the Henderson fee was wasted. In 2014, it seems a bargain, even at £16m.

That £93m spent on those particular four players in 2011 now equates to two sales, and two improved players; £17m from West Ham for Carroll, £5m from West Ham for Downing, and then £25m (increased value of Henderson) and £80m (increased value of Suarez). Two successes, two ‘flops’, and that’s still “£127m”.

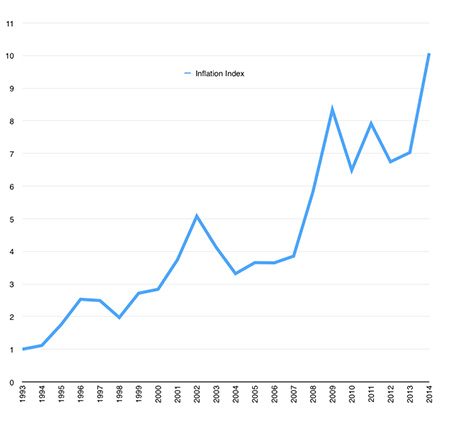

To flip that, transfer fees are now approximately 27% higher than three years ago, as prices rise in keeping with yet another massive TV deal. (Why else would a teenage full-back cost £30m? My view is that people instinctively see transfer fees in terms of what they were two or three earlier, and react without taking inflation into account.)

And yet even at worst, Liverpool could “break even” (adding 27% inflation) on two of the most overpriced purchases of its recent history, and when selling a third, who also happens to have the worst disciplinary record of any Liverpool player I can recall (despite never getting a red card). The investment in 2011 was part of what propelled Liverpool back into the Champions League, with Suarez and Henderson adding a great deal to the campaign.

Truths

Three truths are that Liverpool improved after selling Kevin Keegan, improved after selling Ian Rush and improved after selling Fernando Torres. Each was seen as key to the Reds’ success, yet each gave way to even better players, or a better team. Equally, Liverpool regressed after selling Graeme Souness, Xabi Alonso and Steve McManaman, albeit still with improvement returning within a handful of years, to the point where the Reds were arguably even better than when they had them (with the seasons of 1987, 2001 and 2014 representing some kind of improvement – in some cases a matter of aesthetics – on the best years those stars had at Liverpool).

Luis Suarez turns 28 in January, just a few months after he returns form his third lengthy ban in England, and while he’s clearly at his peak, he maybe has three or four years left at the very top; more if he’s lucky, less if he’s unlucky. His value is at its absolute peak, even taking into account his proclivity for biting. You don’t automatically sell your best players once they are at their peak value, but you must consider the implications. On average, 30-year-olds cost far, far less than 28-year-olds; like a car being driven off a forecourt, their value plummets overnight. Clubs must consider this, if not necessarily panic at the prospect of a key player getting older.

I see no point in panicking about players leaving, full-stop. So long as it’s for a fee commensurate with their ability; so long as it’s not a move to a direct Premier League rival; and so long as the money is reinvested in the team (and not used to pay off loans, as in 2009), then what’s to fear? It’s all part of the cycle of football, and it never changes. You can’t hold onto them forever. They all have to leave, sooner or later, in one way or another. Just as Suarez left Ajax for Liverpool, I can understand him leaving Liverpool for Barcelona.

As I said last year, players are just passing through, albeit at different speeds. They come, they go. The only things you can hold onto are the memories.

Our new book is out now, only on Kindle. (Paperbacks sold out.)